Spanish heraldry

The tradition and art of heraldry first appeared in Spain at about the beginning of the eleventh century AD and its origin was similar to other European countries: the need for knights and nobles to distinguish themselves from one another on the battlefield, in jousts and in tournaments. Knights wore armor from head to toe and were often in leadership positions, so it was essential to be able to identify them on the battlefield.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heraldry of Spain. |

Features

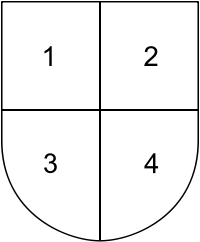

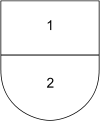

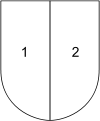

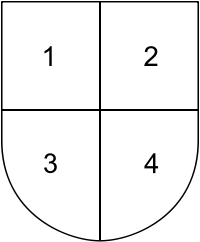

The design of the arms themselves, excepting for the rules of heraldry, were up to the owner, and sometimes the design had a specific meaning or symbolism. Originally, anyone could bear (display) arms. Later, it became more of a practice for the nobility. Until the end of the middle ages only the paternal arms were used but later both the paternal and maternal arms were displayed. The arms of the maternal and paternal grandfathers were impaled (shield cut in half vertically, showing the respective arms on each half). During the 18th and 19th centuries, the use of four quarterings came into use by the nobility (the shield was cut into four parts and the design of the arms of each grandparent was placed in each quarter). The order of display was:

- Paternal grandfather

- Maternal grandfather

- Paternal grandmother

- Maternal grandmother

Origins and history

The Spanish nobility, unlike their other European counterparts, was based almost entirely on military service. Few families of eminence came from the law, commerce or the church. The great families of Spain and Portugal fought their way to their rank, which allowed commoners to join the ranks of the nobility through loyal and successful military service. Many poor families came to prominence and wealth quickly as a result of their successful military exploits. In Spanish heraldry, arms are a symbol of lineage and a symbol of the family as well. Spanish arms are inheritable like any other form of property.

Descent of Spanish arms

.svg.png)

The descent of Spanish arms and titles differs from much of Europe in that they can be inherited through females. Also, illegitimacy did not prevent the descent of arms and titles. The great Spanish families believed that a family pedigree could be more damaged by misalliance than by illegitimacy. Indeed, the patents of nobility of many Spanish families contained bequeathals to illegitimate branches in case no legitimate heirs were found. Illegitimacy in Spain was divided into three categories.

- Natural children: Those born of single or widowed parents who could be legitimized by the marriage of their parents or by a declaration by their father that they were his heirs.

- Spurious children: Those whose parents were not in a position to marry. These children had to be legitimized by a petition of royal ratification.

- Incestuous children: Those born of parents too closely related to marry or who were under a religious vow. These hijos required a papal dispensation in order to inherit their parent's arms or property. These papal dispensations were granted so often that every diocese in Spain had signed blanks ready to affix the appropriate name.

Style and practice

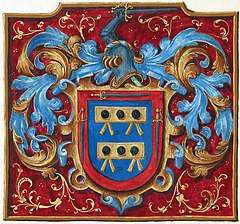

Spanish heraldry style and practice follows the Iberian branch of the Latin heraldry tradition, that also includes the Portuguese heraldry, with which it shares many features. The most common shape of heraldic shield used in Spain is the Iberian style (also referred as "Peninsular", "Spanish" or "Portuguese") which has a simple shape, square on top and round at the bottom. The charges shown on Spanish armorial bearings can depict historical events or deeds of war. They are also characterized by a widespread use of orles and borders around the edge of the shield. In addition to borders, Spain and Portugal marshal arms more conventionally by quartering. The Iberian heraldry also allows words and letters on the shield itself, a practice which is considered incorrect in northern Europe. Crests and helmets are also common in Spain and Portugal.

Definitions

The "coat" of arms, or more correctly the achievement, in Spain is composed of the shield, a cape which can be simply drawn or ornate, a helmet (optional) or a Crown if for a member of the nobility and a motto (optional). In Spanish heraldry, that which is placed on the shield itself is the most important.

In English, Scottish and Irish heraldry one can find many additional accessories not often found or used in Spanish heraldry. They can include, in addition to the shield, a helmet, mantling (cloth cape), wreath (a circle of silk with gold and silver cord twisted around and placed to cover the joint between the helmet and crest), the crest, the motto, chapeau, supporters (animals real or fictitious or people holding up the shield), the compartment (what the supporters are standing on), standards and Ensigns (personal flags), Coronets of rank, insignia of orders of chivalry and badges. In general, the older the arms, the simpler or plainer is the achievement.

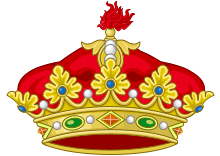

Sovereign – Royal Crown of Spain

Sovereign – Royal Crown of Spain

Design of the national arms.svg.png) Sovereign – Royal Crown of Spain

Sovereign – Royal Crown of Spain

Design of the monarch's arms Sovereign – Variant for the Spanish Territories of the former Crown of Aragon

Sovereign – Variant for the Spanish Territories of the former Crown of Aragon Crown of the Heir Apparent

Crown of the Heir Apparent Heir Apparent – Variant for the Spanish Territories of the former Crown of Aragon

Heir Apparent – Variant for the Spanish Territories of the former Crown of Aragon Infantes (Princes and Princesses)

Infantes (Princes and Princesses) Infantes – Variant for the Spanish Territories of the former Crown of Aragon

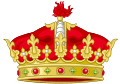

Infantes – Variant for the Spanish Territories of the former Crown of Aragon Heraldic Coronet of Spanish Grandee

Heraldic Coronet of Spanish Grandee.svg.png) Duke

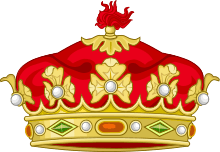

Duke.svg.png) Marquess

Marquess Count

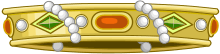

Count Viscount

Viscount Baron

Baron Señor (Lord)

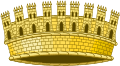

Señor (Lord).svg.png) Spanish Mural Crown (Generic)

Spanish Mural Crown (Generic) Mural Crown of Catalan Provinces (Spain)

Mural Crown of Catalan Provinces (Spain) Mural Crown of Catalan Regions

Mural Crown of Catalan Regions Mural Crown of Catalan Cities

Mural Crown of Catalan Cities Mural Crown of Catalan Towns

Mural Crown of Catalan Towns Mural Crown of Catalan Villages

Mural Crown of Catalan Villages Heraldic Coronet of Spanish Kings of Arms

Heraldic Coronet of Spanish Kings of Arms

Military heraldic coronets[1]

Regulation

The Chronicler King of Arms in the Kingdoms of Spain was a civil servant who had the authority to grant armorial bearings. The office of the King of Arms in Spain originated from those of the heralds (Spanish: heraldos). In the early days of heraldry, anyone could bear arms and there arose disputes between individuals and families. These disputes were originally settled by the King, in the case of a dispute between nobles or by a lower ranked official when the dispute involved non-nobles. Eventually, the task of settling these disputes was passed on to officials called heralds who were originally responsible for setting up tournaments and carrying messages from one noble to another.

The Spanish Cronista de Armas heraldic office dates back to the 16th century. But prior to that, heralds were usually named after provinces and non-capital cities, whilst reyes de armas were named after the Spanish kingdoms. Various chroniclers of arms were named for Spain, Castile, León, Frechas, Seville, Córdoba, Murcia, Granada (created in 1496), Estella, Viana, Navarre, Catalonia, Sicily, Aragon, Naples, Toledo, Valencia and Majorca. While these appointments were not hereditary, at least fifteen Spanish families produced more than one herald each in the past five hundred years (compared to about the same number for England, Scotland and Ireland collectively).[3] The Spanish Cronistas had judicial powers in matters of noble titles. They also served as an accreditation office for pedigrees and grants of arms.

The post of King of Arms took several forms and eventually settled on a Corps of Chronicler King of Arms (Cuerpo de Cronista Rey de Armas) which was headed by an Elder or Dean (Decano). It usually consisted of four officers and two assistants or undersecretaries which usually acted as witnesses to documents. The entire corps wore a distinctive uniform. The corps were considered part of the royal household and was generally responsible to the Master of the King's stable (an important position in the Middle Ages).

Appointments to the Corps of King of Arms were made by the King or reigning Queen. These appointments were for life and while not intended to be hereditary, often went from father to son or other close family member. The Spanish heralds had other duties which pertained to matters of protocol and often acted as royal messengers and emissaries. They could, and can, make arrangements for areas currently or previously under the rule of the Spanish crown [4]

The precise functions and duties of the King of Arms were clearly defined by the declarations of several Kings and are still in force today. In modern times the Corps of Chronicler King of Arms went through several changes. Important changes were made in 1915, it was abolished in 1931 and restored in 1947–1951.[5] The last Chronicler Kings of Arms appointed by the Spanish Ministry of Justice was Don Vicente de Cadenas y Vicent, died in 2005. The government of the autonomous community of Castile and León has appointed Don Alfonso Ceballos-Escalera y Gil, Marques de la Floresta and Vizconde de Ayala as (Chronicler of Arms for Castile and León). Don Alfonso also serves as personal heraldic officer to the King of Spain. Formerly, everything that the Spanish heralds do must be approved by the Ministry of Justice.[6] However, more recent legislation has established the Cronista de Castile and León as the modern equivalent of the Spanish King of Arms with the authority to make grants of arms to citizens of Spain and individuals from families associated with its former colonies without reference to the Ministry of Justice.[7]

National and civic arms

See also Coat of Arms of Spain

.svg.png)

Like most European countries, Spain has a national coat of arms. Many cities also have civic coats of arms; some are recent grants, others date back to the medieval period. Toledo, in previous periods the most important city of Spain, has a particularly elaborate coat of arms; it uses the double-headed eagle of the Holy Roman Empire as supporter on its coat of arms; this represents its former importance and power. Madrid, the capital, has a less elaborate coat of arms, depicting a bear taking fruit from a tree.

Coats of arms are regularly depicted on various buildings and objects belonging to national or local government; in Madrid, even such unglamorous objects as manhole covers are decorated with the civic coat of arms.

Personal arms

Some ancient Spanish families bear personal arms. The Dukes of Alba, historically among the most powerful noble families in Europe, bear an elaborate achievement of arms, featuring the 'arms of justice' symbolising their hereditary office as Constables of Navarre.[8] The monarch and the heir apparent have their own personal coats of arms.

Heraldic regulation

Spain originally had a corporation of heralds (Spanish 'cronistas de armas') linked with the royal palace.[9] However, the Spanish body of heralds was abolished in 1931 with the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic.[10] Since the restoration of Juan Carlos I in 1975, Spain's first post-republican herald has been appointed.

As in other European nations, arms are regulated, and it is unlawful to assume arms belonging to someone else.

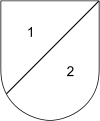

| Example |  |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English name | Party per fess | Party per pale | Party per bend sinister | Quarterly | Quarterly with an inescutcheon |

| Spanish name | Cortado en dos | Partido en dos | En banda En barra (opposite) |

Cuartelado | Cuartelado con escusón |

Spanish coats of arms are divided in the same fashion used by other European countries. Since coats of arms were granted to new separate families, there was the need to join multiple coats of arms into one when a new branch of a family was formed. Thus Spanish escutcheons are commonly parted.

The tradition of differentiating between the coat of arms proper and a lozenge granted to women did not develop in Spain. Both men and women inherited a coat of arms from their fathers (or a member of a clan who had adopted them). In the case of women they could also adopt the arms of their husbands.

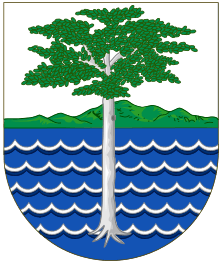

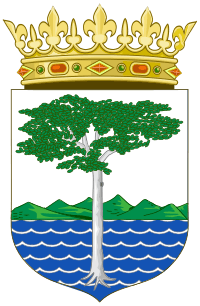

Examples of Spanish heraldry overseas

Current

.svg.png)

Coat of Arms of Durango

Coat of Arms of Durango

(Mexico).svg.png) Coat of Arms of Guadalajara

Coat of Arms of Guadalajara

(Mexico)

.svg.png)

Coat of Arms of Medellín

Coat of Arms of Medellín

(Colombia).svg.png)

.svg.png)

Coat of Arms of

Coat of Arms of

Puebla City

(Mexico) Coat of Arms of

Coat of Arms of

Puerto Rico.svg.png) Coat of Arms of

Coat of Arms of

Puerto Rico

(Aragonese Arms Variant) Great Seal of

Great Seal of

Puerto Rico

Coat of Arms of

Coat of Arms of

S. Antonio

(United States)

.svg.png)

Seal of San Diego

Seal of San Diego

(United States).svg.png)

.svg.png) Coat of Arms of Santiago

Coat of Arms of Santiago

(Chile)

Historical

Spanish Empire

.svg.png) Coat of Arms of Bogota

Coat of Arms of Bogota Coat of Arms of

Coat of Arms of

the Californias Coat of Arms of

Coat of Arms of

Cartagena of the Indies.svg.png) Coat of Arms of Cusco

Coat of Arms of Cusco.svg.png) Coat of Arms of Guatemala City and Antigua

Coat of Arms of Guatemala City and Antigua.svg.png) Coat of Arms of Havana

Coat of Arms of Havana.svg.png) Coat of Arms of Manila

Coat of Arms of Manila Old Coat of Arms of Medellín

Old Coat of Arms of Medellín Modern Coat of Arms of Medellín

Modern Coat of Arms of Medellín.svg.png) Coat of arms of Mexico City

Coat of arms of Mexico City.svg.png) Coat of Arms of

Coat of Arms of

Nueva Galicia-Spanish_Rule.svg.png) Coat of Arms of San Juan City

Coat of Arms of San Juan City Coat of Arms of Yucatan

Coat of Arms of Yucatan

Overseas Provinces

Coat of Arms of

Coat of Arms of

Spanish Guinea

.svg.png)

External links

See also

- Coat of arms of Spain

- Coats of arms of Spanish Monarchs in Italy

- Coats of arms, badges and emblems of Spanish Armed Forces

- Flag of Spain

- List of Spanish flags

- List of coats of arms of Spain

- Symbols of Francoism

References

- Coronets used by Spanish general or senior officers without royal or noble titles.

- García-Menacho y Osset, E. Introducción a la heráldica y manual de heráldica militar española. Madrid: Ministerio de Defensa, 2010. ISBN 978-84-9781-559-8. P. 96

- http://heraldry.freeservers.com/heralds.html

- Official Heraldic Authorities at The International Association of Amateur Heralds.

- Francisco Franco, Decreto del 13 de abril de 1951.

- Cronista Rey de Armas of Castilla and Leon.

- Decreto 105/1991, 9 May (Boletín Oficial de Castilla y León de 16 May 1991)

- p173, Slater, Stephen, The Complete Book of Heraldry (2002, Anness Publishing) ISBN 0-7548-1062-3

- p205, Slater, Stephen, The Complete Book of Heraldry (2002, Anness Publishing) ISBN 0-7548-1062-3

- p205, Slater, Stephen, The Complete Book of Heraldry (2002, Anness Publishing) ISBN 0-7548-1062-3