Soviet re-occupation of Latvia in 1944

The Soviet re-occupation of Latvia in 1944 refers to the military occupation of Latvia by the Soviet Union in 1944.[1] During World War II Latvia was first occupied by the Soviet Union in June 1940 and then was occupied by Nazi Germany in 1941–1944 after which it was re-occupied by the Soviet Union.

Battle of the Baltic

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Latvia |

|

|

Ancient Latvia

|

|

Modern Latvia

|

| Chronology |

|

|

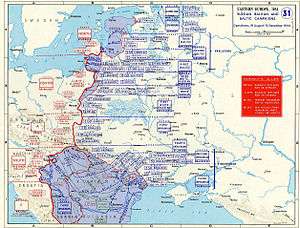

Army Group Centre was in tatters, and the northern edge of the Soviet assault threatened to trap Army Group North in a pocket in the Courland region. Panzers of Hyazinth Graf Strachwitz von Gross-Zauche und Camminetz had been sent back to the capital of Ostland, Riga and in ferocious defensive battles had halted the Soviet advance in late April 1944. Strachwitz had been needed elsewhere, and was soon back to acting as the Army Group's fire brigade. Strachwitz's Panzerverband was broken up in late July. By early August, the Soviets were again ready to attempt to cut off Army Group North from Army Group Centre. A massive Soviet assault sliced through the German lines and Army Group North was completely isolated from its neighbour. Strachwitz was trapped outside the pocket, and Panzerverband von Strachwitz was reformed, this time from elements of the 101st Panzer Brigade of panzer-ace Oberst Meinrad von Lauchert and the newly formed SS Panzer Brigade Gross under SS-Sturmbannführer Gross. Inside the trapped pocket, the remaining panzers and StuG IIIs of the Hermann von Salza and the last of Jähde's Tigers were formed into another Kampfgruppe to attack from the inside of the trap. On 19 August 1944, the assault, which had been dubbed Unternehmen Doppelkopf (Operation Doppelkopf) got underway. It was preceded by a bombardment by the cruiser Prinz Eugen's 203mm guns, which destroyed forty-eight T-34s assembling in the square at Tukums. Strachwitz and the Nordland remnants meet on the 21st, and contact was restored between the army groups. The 101.Panzerbrigade was now assigned to the army detachment "Narwa active at the Emajõgi River Front, bolstering the defenders' armour strength. Disaster had been averted, but the warning was clear. Army Group North was extremely vulnerable to being cut off. In 1944, the Red Army lifted the siege of Leningrad and re-conquered the Baltic area along with much of Ukraine and Belarus.

However, some 200,000 German troops held out in Courland along with Latvian forces resisting Soviet reoccupation. They were besieged with their backs to the Baltic Sea. The Red Army mounted numerous offensives at massive losses but failed to take the Courland Pocket. Colonel-General Heinz Guderian, the Chief of the German General Staff insisted to Adolf Hitler that the troops in Courland should be evacuated by sea and used for the defence of the Third Reich; however, Hitler refused and ordered the German forces in Courland to hold out. He believed them necessary to protect German submarine bases along the Baltic coast.

On January 15, 1945, Army Group Courland (Heeresgruppe Kurland) was formed under Colonel-General Dr. Lothar Rendulic. Until the end of the war, Army Group Courland (including divisions such as the Latvian Freiwiliger SS Legion) successfully defended the Latvian peninsula. It held out until May 8, 1945, when it surrendered under Colonel-General Carl Hilpert, the army group's last commander. He surrendered to Marshal Leonid Govorov, the commander of opposing Soviet forces on the Courland perimeter. At this time the group still consisted of some 31 divisions of varying strength. After May 9, 1945 approximately 203,000 troops of Army Group Courland began moving to Soviet prison camps in the East. The Soviet Union reoccupied Latvia as part of the Baltic Offensive in 1944, a twofold military-political operation to rout German forces and the "liberation of the Soviet Baltic peoples"[2] beginning in summer-autumn 1944, lasting until the capitulation of German and Latvian forces in Courland pocket in May 1945, and they were gradually absorbed into Soviet Union. After World War II, as part of the goal to more fully integrate Baltic countries into the Soviet Union, mass deportations were concluded in the Baltic countries and the policy of encouraging Soviet immigration to Latvia continued.[3] On January 12, 1949 the Soviet Council of Ministers issued a decree "on the expulsion and deportation" from Latvia of "all kulaks and their families, the families of bandits and nationalists", and others. More than 200,000 people are estimated to have been deported from the Baltic in 1940–1953. In addition, at least 75,000 were sent to Gulag. 10 percent of the entire adult Baltic population was deported or sent to labor camps. Many soldiers evaded capture and joined the Latvian national partisans' resistance that waged unsuccessful guerilla warfare for several years.

Wartime expediency

The precedent under international law established by the earlier-adopted Stimson Doctrine, as applied to the Baltics in U.S. Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles's declaration of July 23, 1940, defined the basis for non-recognition of the Soviet Union's forcible incorporation of Latvia.[4] Despite Welles's statement, the Baltics soon reprised their centuries-long role as pawns in the conflicts of larger powers. After visiting Moscow in the winter of 1941–1942, British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden already advocated sacrificing the Baltics to secure Soviet cooperation in the war. The British ambassador to the U.S., Lord Halifax, reported, "Mr. Eden cannot incur the danger of antagonizing Stalin, and the British War Cabinet have... agree[d] to negotiate a treaty with Stalin, which will recognize the 1940 frontiers of the Soviet Union."[5] By 1943 Roosevelt had also consigned the Baltics and Eastern Europe to Stalin. Meeting with Archbishop Spellman in New York on September 3, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt stated, "The European people will simply have to endure Russian domination, in the hope that in ten or twenty years they will be able to live well with the Russians."[6] Meeting with Stalin in Tehran on December 1, Roosevelt "said that he fully realized the three Baltic Republics had in history and again more recently been part of Russia and jokingly added, that when the Soviet armies re-occupied these areas, he did not intend to go to war with the Soviet Union on this point."[7] A month later, Roosevelt related to Otto von Habsburg that he had told the Russians they could take over and control Romania, Bulgaria, Bukovina, Eastern Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, and Finland.[8] The future was sealed when on October 9, 1944 Churchill met with Stalin in Moscow and penciled out the post-war state of Europe. Churchill recounts: "At length I said, 'Might it not be thought rather cynical if it seemed that we had disposed of these issues, so fateful to millions of people, in such an offhand manner? Let us burn the paper.' — 'No, you keep it,' said Stalin."[9] The February 1945 Yalta Conference, widely ascribed as determining the future of Europe, essentially codified Churchill's and Roosevelt's prior private commitments to Stalin not to interfere in Soviet control of Eastern Europe.

Treaties the USSR signed between 1940 and 1945

The Soviet Union joined the Atlantic Charter of August 14, 1941 by resolution, signed in London on September 24, 1941.[10] Resolution affirmed:

- "First, their countries seek no aggrandizement, territorial or other;

- "Second, they desire to see no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned;

- "Third, they respect the rights of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them. ..."[11]

Most importantly, Stalin personally reaffirmed the principles of the Atlantic Charter on November 6, 1941:[12]

We have not and cannot have any such war aims as the seizure of foreign territories and the subjugation of foreign peoples whether it be peoples and territories of Europe or the peoples and territories of Asia....

We have not and cannot have such war aims as the imposition of our will and regime on the Slavs and other enslaved peoples of Europe who are awaiting our aid.

Our aid consists in assisting these peoples in their struggle for liberation from Hitler's tyranny, and then setting them free to rule on their own lands as they desire. No intervention whatever in the internal affairs of other nations.

Soon thereafter, the Soviet Union signed the Declaration by United Nations of January 1, 1942, which again confirmed adherence to the Atlantic Charter.

The Soviet Union signed the Yalta Declaration on Liberated Europe of February 4–11, 1945, in which Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt jointly declare for the reestablishment of order in Europe according to the principle of the Atlantic Charter "the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live, the restoration of sovereign rights and self-government to those peoples who have been forcibly deprived of them by the aggressor nations." The Yalta declaration further states that "to foster the conditions in which the liberated peoples may exercise these rights, the three governments will join ... among others to facilitate where necessary the holding of free elections."[13]

Finally, the Soviet Union signed the Charter of the United Nations on October 24, 1945, which in Article I Part 2 states that one of the "purposes of the United Nations is to develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples."

Latvian losses

World War II losses in Latvia were among the highest in Europe. Estimates of population loss stand at 30% for Latvia. War and occupation deaths have been estimated at 180,000 in Latvia. These include the Soviet deportations in 1941, the German deportations, and Holocaust victims.[14]

See also

- Soviet occupation of Latvia in 1940

- Soviet occupation of the Baltic states (1944)

- Occupation of Latvia by Nazi Germany

- Holocaust in Latvia

- Latvian national partisans

- The Barricades

- Litene

- Occupations of Latvia

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Rainiai massacre

- United States resolution on the 90th anniversary of the Latvian Republic

- Swedish extradition of Baltic soldiers

- Museum of the Occupation of Latvia

- Serov Instructions

- NKVD Order No. 001223

Notes

- Country Profiles: Latvia at UK Foreign Office

- Д. Муриев, Описание подготовки и проведения балтийской операции 1944 года, Военно-исторический журнал, сентябрь 1984. Translation available, D. Muriyev, Preparations, Conduct of 1944 Baltic Operation Described, Military History Journal (USSR Report, Military affairs), 1984–9, pp. 22–28

- Background Note: Latvia at US Department of State

- Latvia: Latvia By David J. Smith; Page 138

- Harriman, Averell & Abel, Elie. Special Envoy to Churchill and Stalin 1941–1946, Random House, New York. 1974. p. 1135.

- Gannon, Robert. The Cardinal Spellman Story. Doubleday, New York. 1962. pp. 222–223

- Minutes of meeting, Bohlen, recording. Foreign Relations of the United States, The Conferences of Cairo and Teheran, 1943, pp. 594–596

- Bullitt, Orville. For the President: Personal and Secret. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston. 1972. p. 601.

- Churchill, Winston. The Second World War (6 volumes). Houghton-Mifflin, Boston. 1953. v. 6. pp. 227–228.

- B. Meissner, Die Sowjetunion, die Baltischen Staaten und das Volkerrecht, 1956, pp. 119–120.

- Louis L. Snyder, Fifty Major Documents of the Twentieth Century, 1955, p. 92.

- Embassy of the U.S.S.R., Soviet War Documents (Washington, D.C.: 1943), p. 17 as quoted in Karski, Jan. The Great Powers and Poland, 1919–1945, 1985, on 418

- Foreign Relations of the United States, The Conference at Malta and Yalta, Washington, 1955, p. 977.

- Latvia, World War II losses at Encyclopædia Britannica

References

- Petrov, Pavel (2008). Punalipuline Balti Laevastik ja Eesti 1939–1941 (in Estonian). Tänapäev. ISBN 978-9985-62-631-3.

- Brecher, Michael; Jonathan Wilkenfeld (1997). A Study of Crisis. University of Michigan Press. p. 596. ISBN 9780472108060.

- O'Connor, Kevin (2003). The History of Latvia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 113–145. ISBN 9780313323553.

- Rislakki, Jukka (2008). The Case for Latvia. Disinformation Campaigns Against a Small Nation. Fourteen Hard Questions and Straight Answers about a Baltic Country. Rodopi. ISBN 9789042024243.

- Plakans, Andrejs (2007). Experiencing Totalitarianism: The Invasion and Occupation of Latvia by the USSR and Nazi Germany 1939–1991. AuthorHouse. p. 596. ISBN 9781434315731.

- Wyman, David; Charles H. Rosenzveig (1996). The World Reacts to the Holocaust. JHU Press. pp. 365–381. ISBN 9780801849695.

- Frucht, Richard (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 132. ISBN 9781576078006.

Further reading

- Mälksoo, Lauri (2003). Illegal Annexation and State Continuity: The Case of the Incorporation of Latvia by the USSR. Leiden – Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-411-2177-3

- The Occupation museum of Latvia

- Leonas Cerskus Crimes of Soviet Communists — Wide collection of sources and links

- Non-Recognition in the Courts: The Ships of the Baltic Republics by Herbert W. Briggs. In The American Journal of International Law Vol. 37, No. 4 (Oct., 1943), pp. 585–596.

- The Soviet Occupation of Latvia, by Irina Saburova. In Russian Review, 1955

- Soviet Aggression Against Latvia by (Latvian Supreme Court justice) Augusts Rumpeters — Short and thoroughly annotated dissertation on Soviet-Baltic treaties and relations. 1974. Full text

- The Steel Curtain, TIME Magazine, April 14, 1947

- The Iron Heel, TIME Magazine, December 14, 1953