Sovereign (British coin)

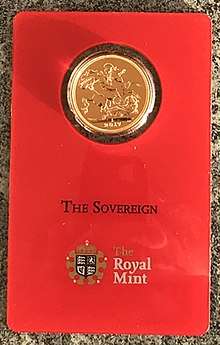

The sovereign is a gold coin of the United Kingdom, with a nominal value of one pound sterling. Struck from 1817 until the present time, it was originally a circulating coin accepted in Britain and elsewhere in the world; it is now a bullion coin and is sometimes mounted in jewellery. In most recent years, it has borne the design of Saint George and the Dragon on the reverse; the initials (B P) of the designer, Benedetto Pistrucci, are visible to the right of the date.

United Kingdom | |

| Value | 1 pound sterling |

|---|---|

| Mass | 7.98805 g |

| Diameter | 22.05 mm |

| Thickness | 1.52 mm |

| Edge | Milled (some not intended for circulation have plain edge) |

| Composition | .917 gold, .083 copper or other metals |

| Gold | 0.2354 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1817–present |

| Mint marks | Various. Found on reverse on exergue between design and date for Saint George and the Dragon sovereigns, and under the wreath for shield back sovereigns, or below bust on obverse on earlier Australian issues. |

| Obverse | |

| |

| Design | Reigning British monarch |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | Saint George and the Dragon |

| Designer | Benedetto Pistrucci |

| Design date | 1817 |

The coin was named after the English gold sovereign, last minted about 1603, and originated as part of the Great Recoinage of 1816. Many in Parliament believed a one-pound coin should be issued rather than the 21-shilling (£1.05) guinea struck until that time. The Master of the Mint, William Wellesley Pole, had Pistrucci design the new coin, and his depiction was also used for other gold coins. Originally, the coin was unpopular as the public preferred the convenience of banknotes, but paper currency of value £1 was soon limited by law. With that competition gone, the sovereign not only became a popular circulating coin, but was used in international trade and in foreign lands, trusted as a coin containing a known quantity of gold.

The British government promoted the use of the sovereign as an aid to international trade, and the Royal Mint took steps to see that lightweight gold coins were withdrawn from circulation. From the 1850s until 1932, the sovereign was also struck at colonial mints, initially in Australia, and later in Canada, South Africa and India—they have been struck again in India since 2013 (in addition to the production in Britain by the Royal Mint) for the local market. The sovereigns issued in Australia initially carried a unique local design, but by 1887, all new sovereigns bore Pistrucci's George and Dragon design. Strikings there were so large that by 1900, about 40 per cent of the sovereigns in Britain had been minted in Australia.

With the start of the First World War in 1914, the sovereign vanished from circulation in Britain, replaced by paper money, and it did not return after the war, though issues at colonial mints continued until 1932. The coin was still used in the Middle East, and demand rose in the 1950s, which the Royal Mint eventually responded to by striking new sovereigns in 1957. It has been struck since then both as a bullion coin and, beginning in 1979, for collectors. Though the sovereign is no longer in circulation, it is still legal tender in the United Kingdom.

Background and authorisation

There had been an English coin known as the sovereign, first authorised by Henry VII in 1489. It had a diameter of 42 millimetres (1.7 in), and weighed 15.55 grams (0.500 oz t), twice the weight of the existing gold coin, the ryal. The new coin was struck in response to a large influx of gold into Europe from West Africa in the 1480s, and Henry at first called it the double ryal, but soon changed the name to sovereign.[1] Too great in value to have any practical use in circulation, the original sovereign likely served as a presentation piece to be given to dignitaries.[2]

The English sovereign, the country's first coin to be valued at one pound,[3] was struck by the monarchs of the 16th century, the size and fineness often being altered. James I, when he came to the English throne in 1603, issued a sovereign in the year of his accession,[4] but the following year, soon after he proclaimed himself King of Great Britain, France[lower-alpha 1] and Ireland, he issued a proclamation for a new twenty-shilling piece. About ten per cent lighter than the final sovereigns, the new coin was called the unite, symbolising that James had merged the Scottish and English crowns.[5]

In the 1660s, following the Restoration of Charles II and the mechanisation of the Royal Mint that quickly followed, a new twenty-shilling gold coin was issued. It had no special name at first but the public soon nicknamed it the guinea and this became the accepted term.[6] Coins were at the time valued by their precious metal content, and the price of gold relative to silver rose soon after the guinea's issuance. Thus, it came to trade at 21 shillings or even sixpence more. Popular in commerce, the coin's value was set by the government at 21 shillings in silver in 1717, and was subject to revision downwards, though in practice this did not occur.[7] The term sovereign, referring to a coin, fell from use—it does not appear in Samuel Johnson's dictionary, compiled in the 1750s.[8]

The British economy was disrupted by the Napoleonic Wars, and gold was hoarded. Among the measures taken to allow trade to continue was the issue of one-pound banknotes. The public came to like them as more convenient than the odd-value guinea. After the war, Parliament, by the Coinage Act 1816, placed Britain officially on the gold standard, with the pound to be defined as a given quantity of gold. Almost every speaker supported having a coin valued at twenty shillings, rather than continuing to use the guinea.[9] Nevertheless, the Coinage Act did not specify which coins the Mint should strike.[10] A committee of the Privy Council recommended gold coins of ten shillings, twenty shillings, two pounds and five pounds be issued, and this was accepted by George, Prince Regent on 3 August 1816.[11] The twenty-shilling piece was named a sovereign, with the resurrection of the old name possibly promoted by antiquarians with numismatic interests.[8]

Creation

William Wellesley Pole, elder brother of the Duke of Wellington, was appointed Master of the Mint (at that time a junior government position) in 1812, with a mandate to reform the Royal Mint. Pole had favoured retaining the guinea, due to the number extant and the amount of labour required to replace them with sovereigns.[12] Formal instruction to the Mint came with an indenture dated February 1817, directing the Royal Mint to strike gold coins weighing 7.988 grams,[lower-alpha 2] that is to say, the new sovereign.[14]

The Italian sculptor Benedetto Pistrucci came to London early in 1816. His talent opened the doors of the capital's elite,[15] among them Lady Spencer, who showed Pistrucci a model in wax of Saint George and the Dragon by Nathaniel Marchant and commissioned him to reproduce it in the Greek style as part of her husband's regalia as a Knight of the Garter. Pistrucci had already been thinking of such a work, and he produced the cameo.[16] The model for the saint was an Italian waiter at Brunet's Hotel in Leicester Square, where he had stayed after coming to London.[17]

In 1816, Pole hired Pistrucci to create models for the new coinage.[18] After completing Lady Spencer's commission, by most accounts, Pistrucci suggested to Pole that an appropriate subject for the sovereign would be Saint George.[19][20] He created a head, in jasper, of King George III, to be used as model for the sovereign and the smaller silver coins. He had prepared a model in wax of Saint George and the Dragon for use on the crown; this was adapted for the sovereign. The Royal Mint's engravers were not able to successfully reproduce Pistrucci's imagery in steel, and the sculptor undertook the engraving of the dies himself.[21]

Pistrucci's George and Dragon design

Pistrucci's design for the reverse of the sovereign features Saint George on horseback. His left hand clutches the rein of the horse's bridle, and he does not wear armour, other than on his lower legs and feet, with his toes bare. Further protection is provided by the helmet, with, on early issues, a streamer or plume of hair floating behind. Also flowing behind the knight is his chlamys, or cloak; it is fastened in front by a fibula. George's right shoulder bears a baltens for suspending the gladius, the sword that he grasps in his right hand.[22] He is otherwise naked[23]—the art critic John Ruskin later considered it odd that the saint should be unclothed going into such a violent encounter.[24] The saint's horse appears to be half attacking, half shrinking from the dragon, which lies wounded by George's spear and in the throes of death.[23]

The original 1817 design had the saintly knight still carrying part of the broken spear. This was changed to a sword when the garter that originally surrounded the design was eliminated in 1821, and George is intended to have broken his spear earlier in the encounter with the dragon.[25] Also removed in 1821 was the plume of hair, or streamer, behind George's helmet; it was restored in 1887,[26] modified in 1893 and 1902,[22] and eliminated in 2009.[27]

The George and Dragon design is in the Neoclassical style. When Pistrucci created the coin, Neoclassicism was all the rage in London, and he may have been inspired by the Elgin Marbles, which were exhibited from 1807, and which he probably saw soon after his arrival in London. Pistrucci's sovereign was unusual for a British coin of the 19th century in not having a heraldic design, but this was consistent with Pole's desire to make the sovereign look as different from the guinea as possible.[28]

Circulation years (1817–1914)

Early years (1817–1837)

Proclamation of George, Prince Regent, 1 July 1817[29]

When the sovereign entered circulation in late 1817, it was not initially popular, as the public preferred the convenience of the banknotes the sovereign had been intended to replace. Lack of demand meant that mintages dropped from 2,347,230 in 1818 to 3,574 the following year.[30] Another reasons why few sovereigns were struck in 1819 was in furtherance of a proposal, eventually rejected, by economist David Ricardo to eliminate gold as a coinage metal, though making it available on demand from the Bank of England. Once this plan was abandoned in 1820, the Bank encouraged the circulation of gold sovereigns, but acceptance among the British public was slow. As difficulties over the exchange of wartime banknotes were overcome, the sovereign became more popular, and with low-value banknotes becoming scarcer, in 1826 Parliament prohibited the issuance of notes with a value of less than five pounds in England and Wales.[31]

The early sovereigns were heavily exported; in 1819, Robert Peel estimated that of the some £5,000,000 in gold struck in France since the previous year, three-quarters of the gold used had come from the new British coinage, melted down.[31] Many more sovereigns were exported to France in the 1820s as the metal alloyed with the gold contained silver, which could be profitably recovered, with the gold often returned to Britain and struck again into sovereigns. Beginning in 1829, the Mint was able to eliminate the silver, but the drain on sovereigns from before this continued.[32]

George III died in January 1820, succeeded by George, Prince Regent, as George IV. Mint officials decided to continue to use the late king's head on coinage for the remainder of the year.[33] For King George IV's coinage, Pistrucci modified the George and Dragon reverse, eliminating the surrounding Garter ribbon and motto, with a reeded border substituted. Pistrucci also modified the figure of the saint, placing a sword in his hand in place of the broken lance seen previously, eliminating the streamer from his helmet, and refining the look of the cloak.[34]

The obverse design for George IV's sovereigns featured a "Laureate head" of George IV, based on the bust Pistrucci had prepared for the Coronation medal. The new version was authorised by an Order in Council of 5 May 1821. These were struck every year between 1821 and 1825, but the King was unhappy with the depiction of him and requested a new one be prepared, based on a more flattering bust by Francis Chantrey. Pistrucci refused to copy the work of another artist and was barred from further work on the coinage. Second Engraver (later Chief Engraver) William Wyon was assigned to translate Chantrey's bust into a coin design, and the new sovereign came into use during 1825. It did not bear the George and Dragon design, as the new Master of the Mint, Thomas Wallace, disliked several of the current coinage designs, and had Jean Baptiste Merlen of the Royal Mint prepare new reverse designs.[35] The new reverse for the sovereign featured the Ensigns Armorial, or royal arms of the United Kingdom, crowned, with the lions of England seen in two of the quarters, balanced by that of Scotland and the harp of Ireland. Set on the shield are the arms of Hanover,[lower-alpha 3] again crowned, depicting the armorial bearings of Brunswick, Lüneburg and Celle. The George and Dragon design would not again appear on the sovereign until 1871.[36]

William IV's accession in 1830 upon the death of his brother George led to new designs for the sovereign, with the new King's depiction engraved by William Wyon based on a bust by Chantrey. Two slightly different busts were used, with what is usually called the "first bust" used for most 1831 circulating pieces (the first year of production) and some from 1832, with the "second bust" used for the prototype pattern coins that year, as well as for proof coins of 1831, some from 1832 and taking over entirely by 1833. The reverse shows another depiction by Merlen of the Ensigns Armorial, with the date accompanied by the Latin word "Anno", or year. These were struck every year until the year of the King's death, 1837.[37]

Victorian era

The accession of Queen Victoria in 1837 ended the personal union between Britain and Hanover, as under the latter's Salic Law, a woman could not take the Hanoverian throne. Thus, both sides of the sovereign had to be changed.[38] Wyon designed his "Young head" portrait of the Queen, which he engraved, for the obverse, and Merlen engraved the reverse, depicting the royal arms inside a wreath, and likely played some part in designing it. The new coin was approved on 26 February 1838, and with the exception of 1840 and 1867, the "shield back" sovereign was struck at the Royal Mint in London every year from 1838 to 1874.[39] Sovereigns struck at London with the shield design between 1863 and 1874 bear small numbers under the shield, representing which coinage die was used. Records of why the numbers were used are not known to survive, with one widely printed theory that they were used to track die wear.[40]

By 1850, some £94 million in sovereigns and half sovereigns had been struck and circulated widely, well beyond Britain's shores, a dispersion aided by the British government, who saw the sovereign's use as an auxiliary to their imperialist ambitions. Gold is a soft metal, and the hazards of circulation tended to make sovereigns lightweight over time. In 1838, when the legacy of James Smithson was converted into gold in preparation for transmission to the United States, American authorities requested recently-struck sovereigns, likely to maximise the quantity of gold when the sovereigns were melted after arrival in the United States. By the early 1840s, the Bank of England estimated that 20 per cent of the gold coins that came into its hands were lightweight. In part to boost the sovereign's reputation in trade, the Bank undertook a programme of recoinage, melting lightweight gold coins and using the gold for new, full-weight ones.[41] Between 1842 and 1845, the Bank withdrew and had recoined some £14 million in lightweight gold, about one-third of the amount of that metal in circulation. This not only kept the sovereign to standard, it probably removed most of the remaining guineas still in commerce.[42] The unlucky holder of a lightweight gold coin could only turn it in as bullion, would lose at least a penny because of the lightness and often had to pay an equal amount to cover the Bank of England's costs.[43] There was also increased quality control within the Royal Mint; by 1866, every gold and silver coin was weighed individually.[44] The result of these efforts was that the sovereign became, in Sir John Clapham's later phrase, the "chief coin of the world".[45]

The California Gold Rush and other discoveries of the 1840s and 1850s boosted the amount of available gold and also the number of sovereigns struck, with £150 million in sovereigns and half sovereigns coined between 1850 and 1875. The wear problem continued: it was estimated that on average, a sovereign became lightweight after fifteen years in circulation. The Coinage Act 1870 tightened standards at the Royal Mint, requiring sovereigns to be individually tested at the annual Trial of the Pyx rather than in bulk.[46] These standards resulted in a high rejection rate for newly-coined sovereigns, though less than for the half sovereign, which sometimes exceeded 50 per cent.[47] When the Royal Mint was rebuilt in 1882, a deciding factor in the decision to shut down production for renovation rather than move to a new mint elsewhere was the Bank of England's report that there was an abnormally large stock of sovereigns and that no harm would result if they could not be coined at London for a year.[48] Advances in technology allowed sovereigns to be individually weighed by automated machines at the Bank of England by the 1890s and efforts to keep the coin at full weight were aided by an 1889 Act of Parliament which allowed redemption of lightweight gold coin at full face value, with the loss from wear to fall upon the government.[46] The Coinage Act 1889 also authorised the Bank of England to redeem worn gold coins from before Victoria's reign but on 22 November 1890, all gold coins from before her reign were called in by Royal Proclamation and demonetised effective 28 February 1891.[49] Due to an ongoing programme to melt and recoin lightweight pieces, estimates of sovereigns in trade weighing less than the legal minimum had fallen to about 4 per cent by 1900.[46]

The sovereign was seen in fiction: in Dickens's Oliver Twist, Mrs Bumble is paid for her information with 25 sovereigns. Joseph Conrad, in his novels set in Latin America, refers several times to ship captains keeping sovereigns as a ready store of value. Although many sovereigns were melted down for recoining on reaching a foreign land (as were those for the Smithsonian) it was regarded as a circulating coin in dozens of British colonies and even in nations such as Brazil and Portugal.[50]

In 1871, the Deputy Master of the Mint, Sir Charles Fremantle, restored the Pistrucci George and Dragon design to the sovereign, as part of a drive to beautify the coinage.[51] The return of Saint George was approved by the Queen, and authorised by an Order in Council dated 14 January 1871. The two designs were struck side by side in London from 1871 to 1874, and at the Australian branch mints until 1887, after which the Pistrucci design alone was used.[52] The saint returned to the rarely-struck two- and five-pound pieces in 1887, and was placed on the half-sovereign in 1893.[53] Wyon's "Young head" of Queen Victoria for the sovereign's obverse was struck from 1838 until 1887, when it was replaced by the "Jubilee head" by Sir Joseph Boehm.[54] That obverse was criticised and was replaced in 1893 by the "Old head" by Sir Thomas Brock.[55] Victoria's death in 1901 led to a new obverse for her son and successor, Edward VII by George William de Saulles, which began production in 1902; Edward's death in 1910 necessitated a new obverse for his son, George V by Bertram Mackennal. Pistrucci's George and Dragon design continued on the reverse.[56]

Branch mint coinage

The 1851 discovery of gold in Australia quickly led to calls from the local populace for the establishment of a branch of the Royal Mint in the colonies there. Authorities in Adelaide did not wait for London to act, but set up an assay office, striking what became known as the "Adelaide Pound". In 1853, an Order in Council approved the establishment of the Sydney Mint; the Melbourne Mint would follow in 1872, and the Perth Mint in 1899.[58] The act which regulated currency in New South Wales came into force on 18 July 1855 and stipulated that the gold coins were to be called sovereigns and half-sovereigns. They were also to be the same weight, fineness and value as other sovereigns.[59]

Early issues for Sydney, until 1870, depicted a bust of Victoria similar to those struck in Britain, but with a wreath of banksia, native to Australia, in her hair. The reverse was distinctive as well, with the name of the mint, the word AUSTRALIA and the denomination ONE SOVEREIGN on the reverse.[58] These coins were not initially legal tender outside Australia, as there were concerns about the design and about the light colour of the gold used (due to a higher percentage of silver in the alloy) but from 1866 Australian sovereigns were legal tender alongside those struck in London. Beginning in 1870, the designs were those used in London, though with a mint mark "S" or "M" (or, later, "P") denoting their origin. The mints at Melbourne and Sydney were allowed to continue striking the shield design even though it had been abandoned at the London facility, and did so until 1887 due to local popularity. The large issues of the colonial mints meant that by 1900, about 40 per cent of the sovereigns circulating in Britain were from Australia.[58][60] Dies for the Australian coinage were made at London.[61]

Following the Klondike Gold Rush, the Canadian Government asked for the establishment of a Royal Mint branch in Canada. It was not until 1908 that what is now the Royal Canadian Mint, in Ottawa, opened, and it struck sovereigns with the mint mark "C" from 1908 to 1919, excepting 1912, each year in small numbers.[62] Branch mints at Bombay (1918; mint mark "I") and Pretoria (1923–1932; mint mark "SA") also struck sovereigns. Melbourne and Perth stopped striking sovereigns after 1931, with Sydney having closed in 1926.[63] The 1932 sovereigns struck at Pretoria were the last to be issued intended as currency at their face value.[64]

To address the high demand for gold coins in the Indian market, which does not allow gold coins to be imported,[65] the minting of gold sovereigns in India with mint mark I has resumed since 2013. Indian/Swiss joint venture company MMTC-PAMP mints under licence in its facility close to Delhi with full quality control from the Royal Mint.[66] The coins are legal tender in Great Britain.[67]

Trade coin (1914–1979)

In the late 19th century, several Chancellors of the Exchequer had questioned the wisdom of having much of Britain's stock of gold used in coinage. Lord Randolph Churchill proposed relying less on gold coinage and moving to high-value silver coins, and the short-lived double florin or four-shilling piece is a legacy of his views. Churchill's successor, George Goschen, urged the issuance of banknotes to replace the gold coinage, and stated that he would prefer to have £20 million in gold in the Bank of England than 30 million sovereigns in the hands of the public. Fears that widespread forgery of banknotes would shake confidence in the pound ended his proposal.[68]

In March 1914, John Maynard Keynes noted that the large quantities of gold arriving from South Africa were making the sovereign even more important, "The combination of the demand for sovereigns in India and Egypt with London's situation as the distributing centre of the South African gold is rapidly establishing the sovereign as the predominant gold coin of the world. Possibly it may be destined to hold in the future the same kind of international position as was held for several centuries, in the days of a silver standard, by the Mexican dollar."[69]

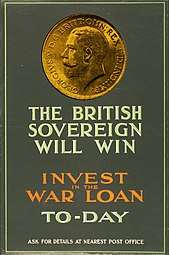

As Britain moved towards war in the July Crisis of 1914, many sought to convert Bank of England notes into gold, and the bank's reserves of that metal fell from £27 million on 29 July to £11 million on 1 August. Following the declaration of war against Germany on 4 August, the government circulated one-pound and ten-shilling banknotes in place of the sovereign and half sovereign.[70] Restrictions were placed on sending gold abroad, and the melting-down of coin made an offence.[71] Not all were enthusiastic about the change from gold to paper: J.J. Cullimore Allen, in his 1965 book on sovereigns, recalled meeting his first payroll after the change to banknotes, with the workers dubious about the banknotes and initially asking to be paid in gold. Allen converted five sovereigns from his own pocket into notes, and the workers made no further objection.[72] Conversion into gold was not forbidden, but the Chancellor, David Lloyd George, made it clear that such actions would be unpatriotic and would harm the war effort. Few insisted on payment in gold in the face of such appeals, and by mid-1915, the sovereign was rarely seen in London commerce. The coin was depicted on propaganda posters, which urged support for the war.[70]

Although sovereigns continued to be struck at London until the end of 1917, they were mostly held as part of the nation's gold reserves, or were paid out for war debts to the United States.[73] They were still used as currency in some foreign countries, especially in the Middle East.[74] Sovereigns continued to be struck at the Australian mints, where different economic circumstances prevailed. After the war, the sovereign did not return to commerce in Britain, with the pieces usually worth more as gold than as currency. In 1925, the Chancellor, Winston Churchill, secured the passage of the Gold Standard Act 1925, restoring Britain to that standard, but with gold to be kept in reserve rather than as a means of circulation. The effort failed—Churchill regarded it as the worst mistake of his life—-but some lightweight sovereigns were melted and restruck dated 1925, and were released only later. Many of the Australian pieces struck in the postwar period were to back currency, while the South African sovereigns were mostly for export and to pay workers at the gold mines.[75][76]

By the time Edward VIII came to the throne in 1936, there was no question of issuing sovereigns for circulation, but pieces were prepared as part of the traditional proof set of coins issued in the Coronation year. With a bust of King Edward by Humphrey Paget and the date 1937, these sovereigns were not authorised by Royal Proclamation prior to the King's abdication in December 1936, and are considered pattern coins.[77] Extremely rare, one sold in 2020 for £1,000,000, setting a record for a British coin.[78] Sovereigns in proof condition dated 1937 were struck for Edward's brother and successor, George VI, also designed by Paget, the only sovereigns to bear George's effigy. The 1925-dated George V sovereign was restruck in 1949, 1951 and 1952, lowering the value of the original, of which only a few had hitherto been known.[79] These were struck to meet the need for sovereigns, and to maintain the skills of the Royal Mint in striking them.[80]

The sovereign remained popular as a trade coin in the Middle East and elsewhere following the Second World War. The small strikings of 1925-dated sovereigns in the postwar period were not enough to meet the demand, which was met in part by counterfeiters in Europe and the Middle East, who often put full value of gold in the pieces. A counterfeiting prosecution was brought, to which the defence was made that the sovereign was no longer a current coin. The judge directed an acquittal although the sovereign remained legal tender under the Coinage Act 1870.[81]

Sovereigns were struck in 1953, the Coronation year of Elizabeth II, bearing the portrait of the Queen by Mary Gillick, though the gold pieces were only placed in the major museums.[82] A 1953 sovereign sold at auction in 2014 for £384,000.[67] In 1957, the Treasury decided to defend the status of the sovereign both by continuing prosecutions, and by issuing new pieces with the current date.[82] Elizabeth II sovereigns bearing Gillick's portrait were struck as bullion pieces between 1957 and 1959, and from 1962 to 1968.[83] The counterfeiting problem was minimised by the striking of about 45,000,000 sovereigns by 1968, and efforts by Treasury solicitors which resulted in the sovereign's acceptance as legal tender by the highest courts of several European nations.[84] In 1966, the Wilson Government placed restrictions on the holding of gold coins to prevent hoarding against inflation, with collectors required to obtain a licence from the Bank of England. This proved ineffective, as it drove gold dealing underground, and was abandoned in 1970.[85]

The sovereign's role in popular culture continued: in the 1957 novel From Russia, with Love, Q issues James Bond with a briefcase, the handle of which contains 50 sovereigns. When held at gunpoint on the Orient Express by Red Grant, Bond uses the gold to distract Grant, leading to the villain's undoing.[86] The sovereign survived both decimalisation and the move of the Royal Mint from Tower Hill, London to Llantrisant, Wales. The last of the Gillick sovereigns had been struck in 1968; when production resumed in 1974, it was with a portrait by Arnold Machin.[87] The last coin minted at Tower Hill, in 1975, was a sovereign.[88]

Bullion and collectors coin (1979 to present)

From 1979, the sovereign was issued as a coin for the bullion market, but was also struck by the Royal Mint in proof condition for collectors, and this issuance of proof coins has continued annually. In 1985, the Machin portrait of the Queen was replaced by one by Raphael Maklouf.[89] Striking of bullion sovereigns had been suspended after 1982, and so the Maklouf portrait, struck every year but 1989 until the end of 1997, is seen on the sovereign only in proof condition.[90] In 1989, a commemorative sovereign, the first, was issued for the 500th anniversary of Henry VII's sovereign. The coin, designed by Bernard Sindall, evokes the designs of that earlier piece, showing the Queen enthroned and facing front, as Henry appeared on the old English sovereign. The reverse of the 1489 piece depicts a double Tudor rose fronted by the royal arms; a similar design with updated arms graces the reverse of the 1989 sovereign.[91]

Ian Rank-Broadley designed the fourth bust of the Queen to be used on the sovereign, and this went into use in 1998 and was used until 2015. Bullion sovereigns began to be issued again in 2000, and this has continued.[92] A special reverse design was used in 2002 for the Golden Jubilee, with an adaptation of the royal arms on a shield by Timothy Noad recalling the 19th-century "shield back" sovereigns.[93] The years 2005 and 2012 (the latter, the Queen's Diamond Jubilee) saw interpretations of the George and Dragon design, the first by Noad, the later by Paul Day. In 2009, the reverse was re-engraved using tools from the reign of George III in the hope of better capturing Pistrucci's design.[94] A new portrait of the Queen by Jody Clark was introduced during 2015, and some sovereigns were issued with the new bust. The most recent special designs, in 2016 and 2017, were only for collectors. The 2016 collector's piece, for the Queen's 90th birthday, has a one-year-only portrait of her on the obverse designed by James Butler. The 2017 collector's piece returned to Pistrucci's original design of 1817 for the modern sovereign's 200th birthday, with the Garter belt and motto. A piedfort was also minted, and the bullion sovereign struck at Llantrisant, though retaining the customary design, was given a privy mark with the number 200.[95][96]

In 2017, a collection of 633 gold sovereigns and 280 half sovereigns was discovered to have been hoarded inside an upright piano which had been donated to a community college in Shropshire, England.[97] The coins, which date from 1847 to 1915, were found by a technician who had been asked to tune the piano, 'stitched into seven cloth packets and a leather drawstring purse' under the piano's keyboard. Despite inquiries being made as to who could have stored the coins, no owner or claimants were found.

Collecting, other use and tax treatment

.jpg)

Many of the variant designs of the sovereign since 1989 have been intended to appeal to coin collectors, as have the other gold coins based on the sovereign, from the quarter sovereign to the five-sovereign piece. To expedite matters, the Royal Mint is authorised to sell gold sovereigns directly to the public, rather than having its output channelled through the Bank of England as was once the case.[98] As a legal tender coin, the sovereign is exempt from capital gains tax for UK residents.[99]

As well as being used as a circulating coin, the sovereign has entered fashion, with some men in the 19th century placing one on their pocket watch chains; wearing one in that fashion came to be seen as a sign of integrity. Others carried their sovereigns in a small purse linked to the watch chain. These customs vanished with the popularisation of the wrist watch. Women also have worn sovereigns, as bangles or ear rings.[100] In the 21st century, the wearing of a sovereign ring has been seen as a sign of chav culture.[101]

Coin auction houses deal in rare sovereigns of earlier date, as do specialist dealers.[102] As well as the 1937 Edward VIII and 1953 Elizabeth II sovereigns, rare dates in the series include the 1819,[103] and the 1863 piece with the number "827" on the obverse in place of William Wyon's initials. The 827 likely is an ingot number, used for some sort of experiment, though research has not conclusively established this.[104] Few 1879 sovereigns were struck at London, and those that remain are often well-worn.[52] Only 24,768 of the Adelaide Pound were struck; surviving specimens are rare and highly prized.[105] The sovereign itself has been the subject of commemoration; in 2005, the Perth Mint issued a gold coin with face value A$25, reproducing the reverse design of the pre-1871 Sydney Mint sovereigns.[106]

See also

- Gold Britannia coin

- Quarter, Half, Double and Quintuple sovereign coins

- Crown gold

Notes

References

- Celtel & Gullbekk, p. 61.

- "Tudor sovereign". The Royal Mint Museum. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Clancy, p. 15.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 3–4.

- Clancy, p. 41.

- Clancy, p. 45.

- Clancy, p. 47.

- Clancy, p. 57.

- Clancy, pp. 52–55.

- Seaby, pp. 116–117.

- Marsh 2017, p. 7.

- Clancy, p. 55.

- "Parliamentary Papers". Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1866. p. 27.

- Clancy, p. 56.

- ODNB.

- Marsh 1996, p. 15.

- Farey September 2014, p. 52.

- Celtel & Gullbekk, p. 91.

- Clancy, p. 58.

- Rodgers, pp. 43–44.

- Marsh 2017, p. 8.

- Allen, p. 13.

- Celtel & Gullbekk, p. 92.

- Clancy, p. 63.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 10–16.

- Celtel & Gullbekk, p. 109.

- Marsh 2017, p. 101.

- Clancy, pp. 62–63.

- Ruding, Rogers (1819). Supplement to the Annals of the Coinage of Britain. London: John Nichols and Son. pp. 47–48. OCLC 778858975. Archived from the original on 2018-02-19.

- Rodgers, p. 44.

- Clancy, pp. 64–67.

- Craig, p. 304.

- Marsh 2017, p. 13.

- Celtel & Gullbekk, p. 98.

- Clancy, pp. 66–67.

- Celtel & Gullbekk, p. 99.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 21–27.

- Clancy, p. 69.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 27–38.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 31, 29.

- Clancy, pp. 70–71.

- Dyer & Gaspar, p. 484.

- Craig, p. 310.

- Craig, p. 322.

- Dyer & Gaspar, p. 511.

- Clancy, pp. 76–77.

- Dyer & Gaspar, pp. 520–521.

- Dyer & Gaspar, p. 525.

- Hayter, p. 433.

- Clancy, pp. 73, 78–79, 85.

- Clancy, p. 73.

- Marsh 2017, p. 47.

- Clancy, p. 65.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 47, 57.

- Marsh 2017, p. 64.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 69, 77.

- Cuhaj, George S., ed. (2009). Standard Catalog of World Coins 1801–1900 (6 ed.). Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-89689-940-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Celtel & Gullbekk, pp. 131–132.

- Pamphlets issued by the New South Wales Commissioners for the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago (1 ed.). New South Wales. Commission for the World's Columbian Exposition. 1893. p. 137.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marsh 2017, pp. 28–29, 64.

- Dyer & Gaspar, pp. 530–531.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 69–72, 81.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 78–87.

- Rodgers, p. 46.

- "Chindambaram rules out lifting ban on import of gold coins". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014.

- "MMTC PAMP Sovereign web page". MMTC PAMP. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- Rodgers, p. 47.

- Clancy, p. 78.

- Keynes, p. 155.

- Clancy, pp. 89–91.

- Josset, pp. 143–144.

- Allen, p. 7.

- Marsh 2017, p. 77.

- Josset, p. 141.

- Clancy, pp. 92–93.

- Allen, p. 10.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 88–89.

- "'Never meant to exist': Edward VIII coin bought for record £1m". The Guardian. PA Media. 17 January 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 90–91.

- Clancy, p. 95.

- Allen, pp. 15–16.

- Clancy, pp. 95–97.

- Marsh 2017, p. 97.

- Dyer & Gaspar, p. 598.

- Seaby, p. 173.

- Clancy, pp. 94–95.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 94, 97–98.

- Clancy, p. 99.

- Celtel & Gullbekk, pp. 116–117.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 98–99.

- Celtel & Gullbekk, pp. 118–119.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 100–101.

- Clancy, p. 102.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 104–105.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 95–96, 106.

- Clancy, pp. 102–103.

- Davies, Caroline (20 April 2017). "Mystery gold sovereign hoard found in piano declared to be treasure". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Clancy, pp. 99–103.

- "Gold and capital gains tax". Royal Mint. 15 November 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Allen, p. 14.

- Rumsey, Nichola; Harcourt, Diana, eds. (2014). Oxford Handbook of the Psychology of Appearance. Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-19-872322-6.

- Marsh 2017, pp. 186–192.

- Marsh 2017, p. 10.

- Marsh 2017, p. 31.

- Allen, pp. 56–57.

- Celtel & Gullbekk, p. 133.

Bibliography

- Allen, James John Cullimore (1965). Sovereigns of the British Empire. London, United Kingdom: Spink & Son, Ltd. OCLC 493287074.

- Celtel, André; Gullbekk, Svein H. (2006). The Sovereign and its Golden Antecedents. Oslo, Norway: Monetarius. ISBN 978-82-996755-6-7.

- Clancy, Kevin (2017) [2015]. A History of the Sovereign: Chief Coin of the World (second ed.). Llantrisant, Wales: Royal Mint Museum. ISBN 978-1-869917-00-5.

- Craig, John (2010) [1953]. The Mint (paperback ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-17077-2.

- Dyer, G.P.; Gaspar, G.P. (1992), "Reform, the New Technology and Tower Hill", in Challis, C.E. (ed.), A New History of the Royal Mint, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, pp. 398–606, ISBN 978-0-521-24026-0

- Farey, Roderick (September 2014). "Benedetto Pistrucci (1782–1855), Part 1". Coin News: 51–53.

- Hayter, Henry Heylyn (1891). Victorian Year-Book for 1890–91 (18th ed.). Melbourne: Sands & McDougall Ltd.

- Hubbard, Arnold (14 July 2003). "How George III lost France: Or, Why Concessions Never Make Sense". Electric Review: A High Tory Online Journal of Politics, Art and Literature. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008.

- Josset, Christopher Robert (1962). Money in Britain. London: Frederick Warne and Co Ltd. OCLC 923302099.

- Keynes, John Maynard (March 1914). "Currency in 1912". The Economic Journal. Royal Economic Society. 24 (93): 152–157. doi:10.2307/2221837. JSTOR 2221837.

- Marsh, Michael A. (1996). Benedetto Pistrucci: Principal Engraver and Chief Medallist of the Royal Mint, 1783-1855. Hardwick, Cambridgeshire: Michael A. Marsh (Publications). ISBN 978-0-9506929-2-0.

- Marsh, Michael A. (2017) [1980]. The Gold Sovereign (revised ed.). Exeter, Devon: Token Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-908828-36-1.

- Pollard, Graham (2004). "Pistrucci, Benedetto". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22314. Retrieved 3 July 2017. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Rodgers, Kerry (June 2017). "Britain's Gold Sovereign". Coin News: 43–47.

- Seaby, Peter (1985). The Story of British Coinage. London: B. A. Seaby Ltd. ISBN 978-0-900652-74-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sovereign (British coin). |