South Lawndale, Chicago

South Lawndale, one of Chicago's 77 well-defined community areas, is on the West Side of the city of Chicago, Illinois. Over 80% of the residents of South Lawndale are of Mexican descent and the community is also home to the largest foreign-born Mexican population in all of Chicago.[2][3] It is notable for having two well-known neighborhoods, Little Village and Marshall Square.[4]

South Lawndale Little Village | |

|---|---|

Community area | |

| Community Area 30 – South Lawndale | |

26th Street in Little Village | |

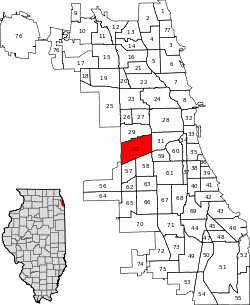

Location within the city of Chicago | |

| Coordinates: 41°51.0′N 87°42.6′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Cook |

| City | Chicago |

| Neighborhoods | List

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.4 sq mi (11.5 km2) |

| Population (2015)[1] | |

| • Total | 73,826 |

| • Density | 17,000/sq mi (6,400/km2) |

| Demographics 2015[1] | |

| • White | 3.07% |

| • Black | 11.05% |

| • Hispanic | 85.24% |

| • Asian | 0.25% |

| • Other | 0.40% |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | parts of 60608 and 60623 |

| Median household income | $30,701[1] |

| Source: U.S. Census, Record Information Services | |

Neighborhoods

Little Village

Little Village, often referred to as the "Mexico of the Midwest," is a dense community in the western and central areas of South Lawndale, with a major commercial district along 26th Street. The area was originally settled by Eastern European and Czech and Bohemian immigrants in the late 19th century, after the Great Chicago Fire sent the population of Chicago rippling out from the city's center to the outlying countryside. Jobs created by industrial development in the early 20th century also attracted residents to the area. Little Village saw a marked increase in Polish immigrants in the mid-20th century.[5]

Mexican and Chicano residents were pushed into the area by the mid-1960s due to segregationist policies in the city of Chicago, which is known as "the most segregated city in the United States." As African American residents were pushed into East Garfield Park and North Lawndale communities, this "forced Chicanos/Mexicanos south into Little Village" and the neighboring community of Pilsen. Scholar Juan C. Guerra notes that "the contiguous communities of Pilsen and Little Village merged and emerged as the newest and largest Mexican neighborhood in Chicago."[6]

Little Village celebrates Mexican Independence Day every September with a parade down 26th Street. It is the largest Hispanic parade in Chicago. The Parade attracts thousands of spectators each year who flock to the neighborhood to show support and pride for their heritage.[7]

Little Village also boasts its economic power in Chicago. Little Village's 26th Street is the second highest grossing shopping district in the city.[8] In 2015, the 2 mile street created $900 million in sales. Its contender, Michigan Avenue, made approximately $1.8 billion that same year.[9]

For green spaces and recreation in Little Village, residents can make a visit to the community parks. Washtenaw Park has a baseball diamond and offers a variety of arts and crafts classes for adults as well as day camps for kids. Shedd Park is a little park in Little Village named for John G. Shedd (known to most Chicagoans as the founder of the Shedd Aquarium). Piotrowski Park is the neighborhood's largest public park and is the most popular outdoor retreat for Little Village residents.

Famous past residents of Little Village include former Mayor Anton Cermak, who lived in the 2300 block of S. Millard Avenue, across the street from Lazaro Cardenas Elementary. Pat Sajak was also a Little Village resident. He attended Gary Elementary School and Farragut High School.

The bulk of Little Village falls within the aldermanic boundaries of the 22nd Ward, represented by Ricardo Muñoz.[10]

In 2011, a music festival called Villapalooza was founded to promote non-violent spaces for arts, culture, and community engagement. This festival has been held yearly and has grown into one of Chicago's most popular and diverse grassroots music festivals drawing both local and international musicians. The festival is free and open to the public.[11]

On August 26, 2018, a fire began early that morning in Little Village. The fire killed ten children, including six children under the age of 12.[12] Investigators stated that the fire started in the back of the building in a ground-floor apartment, which was vacant.[12] The fire was the deadliest residential fire to have occurred in Chicago since 1958.[13] In the aftermath of the fire, multiple violations were found in the apartment where the fire occurred with apartment owner, Merced Gutierrez, appearing in court for the 40 violations found at the site of the fire.

On April 11, 2020, the city of Chicago allowed for the implosion of an old smokestack at the Crawford Coal plant in Little Village carried out by Hilco Redevelopment Partners which sent a large cloud of dust particles into the neighborhood. This sparked outrage and plans for a class action lawsuit.[14] As reported by Mauricio Peña, community activists in Little Village had called upon mayor Lori Lightfoot to stop the implosion before it was carried out, concerned with exposing residents to asbestos and lead, especially during the 2019-2020 coronavirus pandemic.[15]

Marshall Square

Marshall Square is a neighborhood name that is being used by real estate investors, but not the actual residents. It is in the northeast corner of the South Lawndale Community Area, named for the square formed by Marshall Boulevard, 24th Boulevard, Cermak Road, and California Avenue. It is bounded roughly by Kedzie Avenue on the west, 26th Street on the south, the BNSF Railway tracks (2000 South) on the north, and the Western Avenue Corridor railroad tracks (2500 West) on the east. The bulk of the Marshall Square neighborhood falls within the aldermanic boundaries of the 12th Ward. According to the Chicago Museum History Research Center, James A. Marshall, for whom Marshall Boulevard was named, lived in Chicago in the 1830s, opened a dancing school, and served as secretary of the Chicago Real Estate Board in 1833.[16]

Although these days Marshall Square is widely considered by many of its residents to simply be the easternmost part of Little Village, with many businesses in the area using the Little Village name.

Government and infrastructure

Cook County Jail is in South Lawndale.

Politics

The South Lawndale community area has supported the Democratic Party in the past two presidential elections. In the 2016 presidential election, South Lawndale cast 11,878 votes for Hillary Clinton and cast 585 votes for Donald Trump (92.01% to 4.53%).[17] In the 2012 presidential election, South Lawndale cast 9,391 votes for Barack Obama and cast 688 votes for Mitt Romney (91.88% to 6.73%).[18]

Education

Chicago Public Schools operates district public schools, including Farragut Career Academy (the zoned school), Little Village Lawndale High School Campus and Spry Community Links High School.

Harrison Technical High School was previously in South Lawndale.[19]

Enlace Chicago operates within eight Chicago Public Schools in Little Village: Farragut, World Language, Infinity, Social Justice and Multicultural Arts High Schools and at Rosario Castellanos and Madero Middle Schools and Eli Whitney grammar school. "Enlace Chicago Community Schools."

Our Lady of Tepeyac High School is in Little Village.

The United Neighborhood Organization operates the Octavio Paz School in Little Village.[20]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1930 | 76,749 | — | |

| 1940 | 70,915 | −7.6% | |

| 1950 | 66,977 | −5.6% | |

| 1960 | 60,940 | −9.0% | |

| 1970 | 62,821 | 3.1% | |

| 1980 | 75,204 | 19.7% | |

| 1990 | 81,155 | 7.9% | |

| 2000 | 91,071 | 12.2% | |

| 2010 | 79,288 | −12.9% | |

| Est. 2015 | 73,826 | −6.9% | |

| [1][21] | |||

Notable residents

- Jesús "Chuy" García (born 1956), member of the United States House of Representatives from Illinois's 4th congressional district since 2019. He is a longtime resident of South Lawndale and represents it in Congress.[22]

- Pat Sajak (born 1946), television personality and host of Wheel of Fortune. He was a childhood resident of South Lawndale.[23]

See also

References

- "Community Data Snapshot - South Lawndale" (PDF). cmap.illinois.gov. MetroPulse. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- Cutler, Irving (2006). Chicago: Metropolis of the Mid-Continent, 4th Edition. Southern Illinois University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0809327027.

- Paral, Rob (2006). "Latinos of the New Chicago". In Koval, John (ed.). The New Chicago: A Social and Cultural Analysis. Temple University Press. p. 108. ISBN 1592137725.

- Gellman, Erik (2008). Keating, Ann Durkin (ed.). Chicago Neighborhoods and Suburbs: A Historical Guide. University of Chicago Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780226428833.

- "South Lawndale, aka Little Village | WBEZ". www.wbez.org. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- Guerra, Juan C. (1998). Close to Home: Oral and Literate Practices in a Transnational Mexicano Community. Teachers College Press. p. 34. ISBN 9780807737729.

- Gellman, Erik. "Little Village". In Keating, Ann Durkin, ed. (2008). Chicago Neighborhoods and Suburbs: A Historical Guide, p. 198. University of Chicago Press.

- "Check out Chicago's other Mag Mile: 26th Street in Little Village #ccb". Crain's Chicago Business. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- Gerasole, Vince. "Little Village Retail Strip Is Second Highest Grossing in City". Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- http://www.cityofchicago.org/city/en/about/wards/22.html

- "Home". Villapalooza - Little VIllage Music Fest. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- "Apartment Fire Kills 10 Children In Chicago's Little Village Neighborhood". NPR. August 27, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- "Chicago briefings: 44 violations at site of Little Village fire". Daily Herald. September 1, 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- Pathieu, Diane; Elgas, Rob (14 April 2020). "Little Village coal plant smokestack implosion sparks outrage, plans for class action lawsuit". Eyewitness News 7.

- Peña, Mauricio (10 April 2020). "Old Crawford Coal Plant Smokestack Will Be Blown Up Saturday In Little Village". Block Club Chicago.

- “Chicago Streets,” Chicago History Museum Research Center, accessed Jun 19, 2015, http://www.chsmedia.org/househistory/namechanges/start.pdf.

- Ali, Tanveer (November 9, 2016). "How Every Chicago Neighborhood Voted In The 2016 Presidential Election". DNAInfo. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Ali, Tanveer (November 9, 2012). "How Every Chicago Neighborhood Voted In The 2012 Presidential Election". DNAInfo. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Alvarez, René Luis. "A Community that Would Not Take 'No' for an Answer: Mexican Americans, the Chicago Public Schools, and the Founding of Benito Juarez High School," Journal of Illinois History (2014) 17:1 pp 78-98. CITED: p. 88.

- "UNO Charter Schools Archived 2012-04-30 at the Wayback Machine." United Neighborhood Organization. Retrieved on June 16, 2012.

- Paral, Rob. "Chicago Community Areas Historical Data". Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Fremon, David (1988). Chicago Politics, Ward by Ward. Indiana University Press. pp. 146–151.

- Kolker, Claudia (2011). The Immigrant Advantage. Simon and Schuster. p. 130. ISBN 9781416586821. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

Further reading

- Sanchez, Casey. "Turf War: Little Village Fights for Park." Extra. (date unknown) 2005

- Spanish version: (in Spanish) Sanchez, Casey. Translator: Víctor Flores. "GUERRA EN EL CÉSPED: LA Mexico LUCHA POR PARQUE." Extra. (date unknown) 2005.

External links

- Official City of Chicago South Lawndale Community Map

- Enlace Chicago on Facebook

- Little Village Chamber of Commerce

- La Villita Community on Facebook

- La Villita Community on Twitter

- Marshall Square Online

- Maria Saucedo bio

- Marshall Square Theater

- Albaugh-Dover

- St. Agnes of Bohemia in Little Village

- St. Agnes of Bohemia School in Little Village

- Restaurant Dennis B&k in Little Village