Wheel of Fortune (American game show)

Wheel of Fortune (often known simply as Wheel[lower-alpha 1]) is an American television game show created by Merv Griffin that debuted in 1975. The show features a competition in which contestants solve word puzzles, similar to those used in Hangman, to win cash and prizes determined by spinning a giant carnival wheel.

| Wheel of Fortune | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Game show |

| Created by | Merv Griffin |

| Directed by |

|

| Presented by | Host: Hostess: |

| Narrated by | |

| Theme music composer |

|

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language(s) | English |

| No. of episodes | over 7,000 (as of May 31, 2019)[1] |

| Production | |

| Executive producer(s) |

|

| Producer(s) |

|

| Production location(s) | |

| Running time | approx. 22 minutes |

| Production company(s) | |

| Distributor | CBS Television Distribution |

| Release | |

| Original network | |

| Picture format | 480i (SDTV) (1975–2006) 1080i (HDTV; downscaled to 720p locally in some markets) (2006–present) |

| Audio format | Stereo |

| Original release | January 6, 1975 – present |

| Chronology | |

| Related shows | Wheel 2000 |

| External links | |

| Website | |

Wheel originally aired as a daytime series on NBC from January 6, 1975, to June 30, 1989. After some changes were made to its format, the daytime series moved to CBS from July 17, 1989, to January 11, 1991. It then returned to NBC from January 14, 1991, until it was cancelled on September 20, 1991. The popularity of the daytime series led to a nightly syndicated edition being developed, which premiered on September 19, 1983, and has aired continuously since.

The network version was originally hosted by Chuck Woolery and Susan Stafford, with Charlie O'Donnell as its announcer. O'Donnell left in 1980 and was replaced by Jack Clark. After Clark's death in 1988, M. G. Kelly took over briefly as announcer until O'Donnell returned in 1989. O'Donnell remained on the network version until its cancellation, and continued to announce on the syndicated show until his death in 2010, when Jim Thornton succeeded him. Woolery left in 1981, and was replaced by Pat Sajak. Sajak left the network version in January 1989 to host his own late-night talk show, and was replaced on that version by Rolf Benirschke. Bob Goen replaced Benirschke when the network show moved to CBS, then remained as host until the network show was canceled altogether. Stafford left in 1982, and was replaced by Vanna White, who remained on the network show for the rest of its run. The syndicated version has been hosted continuously by Sajak and White since its inception.

Wheel of Fortune ranks as the longest-running syndicated game show in the United States, with 7,000 episodes taped and aired as of May 10, 2019.[1] TV Guide named it the "top-rated syndicated series" in a 2008 article,[3] and in 2013, the magazine ranked it at No. 2 in its list of the 60 greatest game shows ever.[4] The program has also come to gain a worldwide following with sixty international adaptations. The syndicated series' 37th season premiered on September 9, 2019, and Sajak became the longest-running host of any game show, surpassing Bob Barker, who hosted The Price Is Right from 1972 to 2007.[5]

In March 2020, production for Wheel of Fortune was suspended as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. As of August 2020, new episodes of Wheel of Fortune are being produced with new safety measures in place, one of which being a redesigned wheel designed to allow the contestants as well as Pat Sajak to be socially distanced from each other during gameplay. These new episodes are intended to air for the shows' 38th season.

New seasons of Wheel of Fortune typically start in September, however, due to the pandemic, it is unknown when the new season will begin airing. [6] Until the pandemic is over, only essential staff and crew will be allowed on stage, Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) will be provided for everyone behind the scenes and all staff and crew will be tested on a regular basis, while contestants will also be tested before they step onto the set. Social distancing measures will also be enforced off-stage as well. [7]

Gameplay

Main game

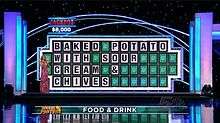

The core game is based on Hangman. Each round has a category and a blank word puzzle, with each blank representing a letter in the answer, and punctuation revealed as needed.[8] Most puzzles are straightforward figures of speech that fit within a mostly static list of categories, and this list has evolved over the course of the series. Crossword puzzles were added to the rotation in 2016. In such rounds, a clue bonding the words in the puzzle is given instead of a traditional category, and contestants win by solving all the words in the crossword.[9] The titular Wheel of Fortune is a roulette-style wheel mechanism with 24 spaces, most of which are labeled with dollar amounts ranging from $500 to $900, plus a top dollar value: $2,500 in round 1, $3,500 in rounds 2 and 3, and $5,000 for round 4 and any subsequent rounds. The wheel also features two Bankrupt wedges and one Lose a Turn, both of which forfeit the contestant's turn, with the former also eliminating any cash or prizes the contestant has accumulated within the round.[10] Each game features three contestants, or occasionally, three two-contestant teams positioned behind a single scoreboard with its own flipper. The left scoreboard from the viewer's perspective is colored red, the center yellow, and the right blue, with the contestants' positions determined by a random selection prior to taping.[11]

A contestant spins the wheel to determine a dollar value and guess a consonant.[lower-alpha 2] Calling a correct letter earns the value before the corresponding flipper, multiplied by the number of times that the letter appears in the puzzle.[13] It also allows the contestant to spin again, buy a vowel for a flat rate of $250, or attempt to solve the puzzle. Contestants may continue to buy vowels so long as they have enough money to keep doing so, until all of the vowels in the puzzle have been revealed.[10] Control passes to the next contestant clockwise if the wheel lands on Lose a Turn or Bankrupt, if the contestant calls a letter that is not in the puzzle, calls a letter that has already been called in that round, fails to call a letter within five seconds of the wheel stopping, or attempts unsuccessfully to solve the puzzle. The only exception is the Free Play wedge, on which the contestant may call a consonant for $500 per occurrence, call a free vowel, or attempt to solve the puzzle, with no penalty for a move that would normally result in a lost turn.

In the first three rounds, the wheel contains a Wild Card and a Gift Tag. The Wild Card may be used to call an additional consonant after any turn (for the amount that the contestant has just spun) or taken to the bonus round to call an extra consonant there. The Gift Tag offers either a $1,000 credit toward purchases from, or $1,000 in cash courtesy of the sponsoring company. A special wedge in the first two rounds awards a prize. All of the tags and the prize wedge are located over the $500 wedges, so calling a letter that appears in the puzzle when landed upon awards both the tag/wedge and $500 per every occurrence of that letter in the puzzle. The first three rounds also contain a special wedge which, if won and taken to the bonus round, offers an opportunity to play that round for $1 million. A contestant must solve the puzzle in order to keep any cash, prizes, or extras accumulated during that round except for the Wild Card, which is kept until the contestant either loses it to Bankrupt or uses it. Bankrupt does not affect score from previous rounds, but it does take away the Wild Card and/or million dollar wedge if either was claimed in a previous round. Contestants who solve a round for less than $1,000 in cash and prizes ($2,000 on weeks with two-contestant teams) have their scores increased to that amount.

Each game also features five toss-up puzzles, which reveal the puzzle one random letter at a time, and award cash to whoever rings in with the right answer. The first puzzle, worth $1,000, determines who the host interviews first; the second, worth $2,000, determines who spins first in round 1. The third through fifth, collectively the "Triple Toss-Up", take place prior to the fourth round. In the Triple Toss-Up round, three consecutive Toss-Up puzzles are played, each having the same category and a common theme. Solving any of these awards $2,000 cash, while solving the third also earns the right to start the fourth round. Contestants may only ring in once for each toss-up puzzle, and no cash is awarded if all three contestants fail to solve the puzzle, or if the last letter is revealed. In this case, the contestant closest to the host goes first. In addition to the toss-ups, each game has a minimum of four rounds, with more played if time permits.[13] Rounds 2 and 3 are respectively started by the next two contestants clockwise from the contestant who began round 1.

Round 2 features two "mystery wedges." Calling a correct letter after landing upon one offers the contestant the chance to accept its face value of $1,000 per letter, or forfeit that amount to flip over the wedge and see whether its reverse side contains a $10,000 cash prize or Bankrupt. Once either mystery wedge is flipped over, the other becomes a standard $1,000 space and cannot be flipped. Round 3 is a prize puzzle, which offers a prize (usually a trip) to the contestant who solves it. Starting with season 31 in 2013, an "Express" wedge is also placed on the wheel in round 3. A contestant who lands on this space and calls a consonant that appears in the puzzle receives $1,000 per appearance. The contestant can then either "pass" and continue the round normally, or "play" and keep calling consonants for $1,000 each (without spinning) and buying vowels for $250. The Express play ends when the contestant either calls an incorrect letter (which has the same effect as landing on a Bankrupt wedge) or solves the puzzle.[14]

The final round is always played at least in part in a "speed-up" format, in which the host spins the wheel; each consonant in that round is worth the value at the red contestant's arrow plus $1,000. If this spin lands on Lose a Turn or Bankrupt, it is edited from the broadcast and the host spins the wheel again. Vowels do not add or deduct money from the contestants' scores in the speed-up round. The contestant in control calls one letter, and if it appears in the puzzle, the contestant is given three seconds to attempt to solve.[lower-alpha 3] Play proceeds clockwise, starting with the contestant who was in control at the time of the final spin, until the puzzle is solved. The three-second timer does not begin until the hostess has revealed all instances of a called letter and moved aside from the puzzle board, and the contestant may offer multiple guesses on his/her turn. After the speed-up round, the contestant with the highest total winnings wins the game and advances to the bonus round. Contestants who did not solve any puzzles are awarded a consolation prize of $1,000 (or $2,000 on weeks with two-contestant teams).

If a tie for first place occurs after the speed-up round, an additional toss-up puzzle is played between the tied contestants. The contestant who solves the toss-up puzzle wins $1,000,[15] and advances to the bonus round.

Bonus round

Since season 35, the winning contestant chooses one of three puzzle categories before the round begins (prior to season 35, the category and puzzle were predetermined). After doing so, the contestant spins a smaller wheel with 24 envelopes to determine the prize. The puzzle is revealed, as is every instance of the letters R, S, T, L, N, and E. The contestant provides three more consonants and one more vowel. A contestant holding the Wild Card may then choose a fourth consonant. After any instances of those letters are revealed, the contestant has 10 seconds to solve the puzzle. The contestant can offer multiple guesses, as long as the contestant begins the correct answer before time expires. Whether or not the contestant solves the puzzle, the host opens the envelope at the end of the round to reveal the prize at stake. Prizes in the bonus round include various cash amounts (with the lowest being the season number multiplied by $1,000), a vehicle (or two vehicles during weeks with two-contestant teams), and a top prize of $100,000.

If the contestant has the Million Dollar Wedge, the $100,000 envelope is replaced with a $1,000,000 envelope.[16] The $1,000,000 prize has been awarded three times: to Michelle Loewenstein (October 14, 2008),[17] Autumn Erhard (May 30, 2013),[18] and Sarah Manchester (September 17, 2014).[19] Contestants who win the $1,000,000 may receive it in installments over 20 years, or in a lump sum of that amount's present value.[20] If the contestant did not land on the $1,000,000, the host reveals the location of the envelope on the prize wheel after the bonus round.

Previous rules

Originally, after winning a round, contestants spent their winnings on prizes that were presented onstage. At any time during a shopping round, most often if the contestant did not have enough left to buy another prize,[21] a contestant could choose to put his or her winnings either on a gift certificate or "on account" for use in a later shopping round. However, a contestant lost any money on account by landing on Bankrupt or failing to claim it by not winning subsequent rounds.[10] The shopping element was eliminated from the syndicated version on the episode that aired October 5, 1987,[22] both to speed up gameplay and to alleviate the taxes paid by contestants.[13] However, the network version continued to use the shopping element until the end of its first NBC run on June 30, 1989.[23]

Before the introduction of toss-up puzzles at the start of the 18th syndicated season in 2000,[24] the contestant at the red arrow always started round 1, with the next contestant clockwise starting each subsequent round.[25] In addition, if a tie for first place occurred, an additional speed-up round was played between the tied contestants for the right to go to the bonus round. If a tie for first place occurred on the daytime version, all three players returned to continue the game on the next episode, and it counted as a single appearance.[26] The wheel formerly featured a Free Spin wedge, which automatically awarded a token that the contestant could turn in after a lost turn to keep control of the wheel.[27] It was replaced in 1989 with a single Free Spin token placed over a selected cash wedge. Free Spin was retired, and Free Play introduced, at the start of the 27th syndicated season in 2009.[28] Between September 16, 1996[29] and the end of season 30 in 2013, the show featured a progressive Jackpot wedge, which had been in several different rounds in its history.[lower-alpha 4] The jackpot started at $5,000 and had the value of every spin within the round added to it. To claim the jackpot, a contestant had to land on the wedge, call a correct letter, and solve the puzzle all in the same turn. In later years, it also offered $500 per correct letter and $500 to the jackpot, regardless of whether or not it was won in that turn.

The network version allowed champions to appear for up to five days originally, which was later reduced to three. The syndicated version, which originally retired contestants after one episode, adopted the three-day champion rule at the start of the seventh season in 1989.[32] In 1996, this was changed to have the top three winners from the week's first four shows returned to compete in the "Friday Finals". When the jackpot wedge was introduced, it began at $10,000 instead of $5,000 on Fridays. The rules allowing returning champions were eliminated permanently beginning with the syndicated episode aired September 21, 1998, and contestants appear only on a single episode, reverting to the pre-1989 rules.[33]

Before December 1981, the show did not feature a permanent bonus round.[10] However, two experimental bonus rounds were attempted before then. In 1978, some episodes featured a round known as the "Star Bonus", where a star-shaped token was placed on the wheel. Contestants who picked up the token played an additional round at the end of the game to win one of four prizes, whose value determined the difficulty of the puzzle. The contestant provided four consonants and a vowel, and was given 15 seconds to attempt solving.[34] In one week of episodes airing in March 1980, contestants who won the main game were given 30 seconds to attempt solving a puzzle for a chance to win a luxury automobile, in a week called "Super Wheel Bonus Week".[35] When the current bonus round was introduced in 1981, no letters were provided automatically. The contestant asked for five consonants and a vowel, and then had fifteen seconds to attempt solving the puzzle. Also, bonus prizes were selected by the contestant at the start of the round.[36] The current time limit and rules for letter selection were introduced on October 3, 1988.[37] Starting on September 4, 1989, the first episode of the seventh syndicated season, bonus prizes were selected by the contestant choosing from one of five envelopes labeled W, H, E, E, and L. One prize was always $25,000 in cash, and the rest were changed weekly. Any prize that was won was taken out of rotation for the rest of the week.[32] During seasons 16 through 18 (1998–2001), the $25,000 remained in-place the entire week of shows regardless if it was won. At the start of season 19 on September 3, 2001, there were three car envelopes and two $25,000 envelopes, which were available the entire week of shows.[38] These envelopes were replaced with the bonus wheel on October 22, 2001.[39]

Conception and development

Merv Griffin conceived Wheel of Fortune just as the original version of Jeopardy!, another show he had created, was ending its 11-year run on NBC with Art Fleming as its host. Griffin decided to create a Hangman-style game after recalling long car trips as a child, on which he and his sister played Hangman. After he discussed the idea with Merv Griffin Enterprises' staff, they thought that the idea would work as a game show if it had a "hook". He decided to add a roulette-style wheel because he was always "drawn to" such wheels when he saw them in casinos. He and MGE's then-president Murray Schwartz consulted an executive of Caesars Palace to find out how to build such a wheel.[40]

When Griffin pitched the idea for the show to Lin Bolen, then the head of NBC's daytime programming division, she approved, but wanted the show to have more glamour to attract the female audience. She suggested that Griffin incorporate a shopping element into the gameplay, and so, in 1973, he created a pilot episode titled Shopper's Bazaar, with Chuck Woolery as host and Mike Lawrence as announcer. The pilot started with the three contestants being introduced individually, with Lawrence describing the prizes that they chose to play for. The main game was played to four rounds, with the values on the wheel wedges increasing after the second round. Unlike the show it evolved into, Shopper's Bazaar had a vertically mounted wheel,[41] which was spun automatically rather than by the contestants. This wheel lacked the Bankrupt wedge and featured a wedge where a contestant could call a vowel for free, as well as a "Your Own Clue" wedge that allowed contestants to pick up a rotary telephone and hear a private clue about the puzzle. At the end of the game, the highest-scoring contestant played a bonus round called the "Shopper's Special" where all the vowels in the puzzle were already there, and the contestant had 30 seconds to call out consonants in the puzzle.

Edd Byrnes, an actor from 77 Sunset Strip, served as host for the second and third pilots, both titled Wheel of Fortune.[42] These pilots were directed by Marty Pasetta, who gave the show a "Vegas" feel that more closely resembled the look and feel that the actual show ended up having, a wheel that was now spun by the contestants themselves, and a lighted mechanical puzzle board with letters that were now manually turnable. Showcase prizes on these pilots were located behind the puzzle board, and during shopping segments a list of prizes and their price values scrolled on the right of the screen. By the time production began in December 1974, Woolery was selected to host, the choice being made by Griffin after he reportedly heard Byrnes reciting "A-E-I-O-U" to himself in an effort to remember the vowels.[42] Susan Stafford turned the letters on Byrnes' pilot episodes, a role that she also held when the show was picked up as a series.[40][43]

Personnel

Hosts and hostesses

The original host of Wheel of Fortune was Chuck Woolery, who hosted the series from its 1975 premiere[10][44] until December 25, 1981, save for one week in August 1980 when Alex Trebek hosted in his place. Woolery's departure came over a salary dispute with show creator Merv Griffin, and his contract was not renewed.[13][45] On December 28, 1981, Pat Sajak made his debut as the host of Wheel.[46] Griffin said that he chose Sajak for his "odd" sense of humor. NBC president and CEO Fred Silverman objected as he felt Sajak, who at the time of his hiring was the weatherman for KNBC-TV, was "too local" for a national audience. Griffin countered by telling Silverman he would stop production if Sajak was not allowed to become host, and Silverman acquiesced.[47]

Sajak hosted the daytime series until January 9, 1989, when he left to host a late-night talk show for CBS. Rolf Benirschke, a former placekicker in the National Football League, was chosen as his replacement and hosted for a little more than five months. Benirschke's term as host came to an end due to NBC's cancellation of the daytime Wheel after fourteen years, with its final episode airing on June 30, 1989.[10] When the newly formatted daytime series returned on CBS on July 17, 1989, Bob Goen became its host. The daytime program continued for a year and a half on CBS, then returned to NBC on January 14, 1991 and continued until September 20, 1991 when it was cancelled for a second and final time.[10]

Susan Stafford was the original hostess, serving in that role from the premiere until October 1982. Stafford was absent for two extended periods, once in 1977 after fracturing two vertebrae in her back and once in 1979 after an automobile accident.[10][48] During these two extended absences, former Miss USA Summer Bartholomew was Stafford's most frequent substitute, with model Cynthia Washington and comedian Arte Johnson also filling in for Stafford.[49]

After Stafford left to become a humanitarian worker,[40] over two hundred applicants signed up for a nationwide search to be her replacement.[50] Griffin eventually narrowed the list to three finalists, which consisted of Summer Bartholomew, former Playboy centerfold Vicki McCarty, and Vanna White.[51] Griffin gave each of the three women an opportunity to win the job by putting them in a rotation for several weeks after Stafford's departure.[13] In December 1982, Griffin named White as Stafford's successor, saying that he felt she was capable of activating the puzzle board letters (which is the primary role of the Wheel hostess) better than anyone else who had auditioned.[52] White became highly popular among the young female demographic,[53] and also gained a fanbase of adults interested in her daily wardrobe, in a phenomenon that has been referred to as "Vannamania".[50] White also hosted the daytime version until its cancellation in 1991, except for one week in June 1986 when Stafford returned so that White could recover after her fiancé, John Gibson, died in a plane crash.[54]

Sajak and White have starred on the syndicated version continuously as host and hostess, respectively, since it began, except for very limited occasions. During two weeks in January 1991, Tricia Gist, the girlfriend and future wife of Griffin's son Tony, filled in for White when she and her new husband, restaurateur George San Pietro, were honeymooning.[55] Gist returned for the week of episodes airing March 11 through 15, 1991, because White had a cold at the time of taping.[56] On an episode in November 1996, when Sajak proved unable to host the bonus round segment because of laryngitis, he and White traded places for that segment.[57][58] On the March 4, 1997 episode, Rosie O'Donnell co-hosted the third round with White after O'Donnell's name was used in a puzzle.[59]

On April 1, 1997, Sajak and Alex Trebek traded jobs for the day. Sajak hosted that day's edition of Jeopardy! in place of Trebek.[60] Trebek presided over a special two-contestant Wheel celebrity match between Sajak and White, who were playing for the Boy Scouts of America and the American Cancer Society, respectively.[61] Lesly Sajak, Pat's wife, was the guest hostess for the day.[60] In January and February 2011, the show held a "Vanna for a Day" contest in which home viewers submitted video auditions to take White's place for one episode, with the winner determined by a poll on the show's website.[62] The winner of this contest, Katie Cantrell of Wooster, Ohio (a student at the Savannah College of Art and Design),[63] took White's place for the second and third rounds on the episode that aired March 24, 2011.

In November 2019, three weeks of episodes were taped with White hosting in Sajak's place while he recovered from intestinal surgery.[64] During her time as hostess, several guests appeared at the puzzle board, including costumed performers of Mickey and Minnie Mouse (during the Secret Santa shows),[65] and Maggie Sajak (Sajak's daughter).[66][67][68]

Announcers

Charlie O'Donnell was the program's first and longest tenured announcer. In 1980, NBC was discussing cancelling Wheel and O'Donnell agreed to take the position as announcer on The Toni Tennille Show. The network decided against the cancellation but O'Donnell decided to honor his commitment and left the series.[69] His replacement was Jack Clark, who added the syndicated series to his responsibilities when it premiered in 1983 and announced for both series until his death in July 1988.[70] Los Angeles radio personality M. G. Kelly was Clark's replacement, starting on the daytime series in August 1988 and on the syndicated series when its new season launched a month later.[71] Kelly held these positions until O'Donnell was able to return to the announcer position, doing so after his duties with Barris Industries came to an end at the end of the 1988–89 television season.[10] O'Donnell remained with the series until shortly before his death in November 2010.[72] Don Pardo, Don Morrow, and Johnny Gilbert have occasionally served as substitute announcers.[10]

After O'Donnell's death, the producers sought a permanent replacement, and a series of substitutes filled out the rest of the season, including Gilbert, John Cramer, Joe Cipriano, Rich Fields, Lora Cain, and Jim Thornton. For the show's twenty-ninth season, which began in 2011, Thornton was chosen to be the show's fourth announcer.[73]

Production staff

Wheel of Fortune typically employs a total of 100 in-house production personnel, with 60 to 100 local staff joining them for those episodes that are taped on location.[11] Griffin was the executive producer of the network version throughout its entire run, and served as the syndicated version's executive producer until his retirement in 2000. Since 1999, the title of executive producer has been held by Harry Friedman, who had shared his title with Griffin for his first year,[74] and had earlier served as a producer starting in 1995.[2]

On August 1, 2019, Sony Pictures Television announced that Friedman would retire as executive producer of both Wheel and Jeopardy! at the end of the 2019–20 season.[75]. On August 29, 2019, Sony Pictures Television announced that Mike Richards will replace Friedman at the start of 2020–21 season.[76]

John Rhinehart was the program's first producer, but departed in August 1976 to become NBC's West Coast Daytime Program Development Director. Afterwards, his co-producer, Nancy Jones, was promoted to sole producer, and served as such until 1995, when Friedman succeeded her.[2] In the 15th syndicated season in 1997, Karen Griffith and Steve Schwartz joined Friedman as producers. They were later promoted to supervising producers, with Amanda Stern occupying Griffith's and Schwartz's former position.[74]

The show's original director was Jeff Goldstein, who was succeeded by Dick Carson (a brother of Johnny Carson) in 1978.[10] Mark Corwin, who had served as associate director under Carson, took over for him upon his retirement at the end of the 1998–99 season, and served as such until he himself died in July 2013 (although episodes already taped before his death continued airing until late 2013).[77] Jeopardy! director Kevin McCarthy,[78] Corwin's associate director Bob Cisneros,[79] and Wheel and Jeopardy! technical director Robert Ennis[80] filled in at various points until Cisneros became full-time director in November 2013.[81] Ennis returned as guest director for the weeks airing October 13 through 17 and November 17 through 21, 2014, as Cisneros was recovering from neck surgery at the time of taping.[82][83] With the start of the 33rd season on September 14, 2015, Ennis was promoted to full-time director.[84]

Production

Wheel of Fortune is owned by Sony Pictures Television (previously known as Columbia TriStar Television, the successor company to original producer Merv Griffin Enterprises).[85] The production company and copyright holder of all episodes to date is Califon Productions, Inc., which like SPT has Sony Pictures for its active registered agent, and whose name comes from a New Jersey town where Griffin once owned a farm.[86] The rights to distribute the show worldwide are owned by CBS Television Distribution, into which original distributor King World Productions was folded in 2007.[87]

The show was originally taped in Studio 4 at NBC Studios in Burbank.[88] Upon NBC's 1989 cancellation of the network series, production moved to Studio 33 at CBS Television City in Los Angeles, where it remained until 1995.[89] Since then, the show has occupied Stage 11 at Sony Pictures Studios in Culver City.[90] Some episodes are also recorded on location, a tradition which began with two weeks of episodes taped at Radio City Music Hall in late 1988.[91] Recording sessions usually last for five or six episodes in one day.[11]

Set

Various changes have been made to the basic set since the syndicated version's premiere in 1983. In 1996, a large video display was added center stage, which was then upgraded in 2003 as the show began the transition into high-definition broadcasting. In the mid-1990s, the show began a long-standing tradition of nearly every week coming with its own unique theme. As a result, in addition to its generic design, the set also uses many alternate designs, which are unique to specific weekly sets of themed programs. The most recent set design was conceived by production designer Renee Hoss-Johnson, with later modifications by Jody Vaclav.[92] Previous set designers included Ed Flesh[93] and Dick Stiles.[92]

Shopper's Bazaar used a vertically mounted wheel which was often difficult to see on-screen. Ed Flesh, who also designed the sets for The $25,000 Pyramid and Jeopardy!, redesigned the wheel mechanism, in which the wheel lays flat while a camera zooms in from above.[94] The first incarnation of the wheel was mostly made of paint and cardboard, and has since seen multiple design changes.[93] Until the mid-1990s, the wheel spun automatically during the opening and closing of the show. The current incarnation, in use since 2003, is framed on a steel tube surrounded by Plexiglas panels and contains more than 200 lighting instruments. It is held by a stainless steel shaft with roller bearings. Altogether, the wheel weighs approximately 2,400 pounds (1,100 kg).[11] The wheel, including its light extensions, is 16.5 ft (5.0 m) in diameter.[95]

The show's original puzzle board had three rows of 13 manually operated trilons, for a total of 39 spaces. On December 21, 1981, a larger board with 48 trilons in four rows (11, 13, 13 and 11 trilons) was adopted. This board was surrounded by a double-arched border of lights which flashed at the beginning and end of the round. Each trilon had three sides: a green side to represent spaces not used by the puzzle, a blank side to indicate a letter that had not been revealed, and a side with a letter on it.[25] While the viewer saw a seamless transition to the next puzzle, with these older boards in segments where more than one puzzle was present, a stop-down of taping took place during which the board was wheeled offstage and the new puzzle loaded in by hand out of sight of the contestants. On February 24, 1997, the show introduced a computerized puzzle board composed of 52 touch-activated monitors in four rows (12 on the top and bottom rows, 14 in the middle two).[11] To illuminate a letter during regular gameplay, the hostess touches the right edge of the monitor to reveal it.[96] The computerized board obviated the stop-downs, allowing tapings to finish quicker at a lower cost to the production company.

Although not typically seen by viewers, the set also includes a used letter board that shows contestants which letters are remaining in play, a scoreboard that is visible from the contestants' perspective, and a countdown clock.[97][98] The used letter board is also used during the bonus round, and in at least one case, helped the contestant to see unused letters to solve a difficult puzzle.[99]

Music

Alan Thicke composed the show's original theme, which was titled "Big Wheels". In 1983, it was replaced by Griffin's own composition, "Changing Keys",[100] to allow him to derive royalties from that composition's use on both the network and syndicated versions. Steve Kaplan became music director starting with the premiere of the 15th syndicated season in 1997, and continued to serve as such until he was killed when the Cessna 421C Golden Eagle he was piloting crashed into a home in Claremont, California, in December 2003.[101] His initial theme was a remix of "Changing Keys", but by the 18th syndicated season (2000–01), he had replaced it with a composition of his own, which was titled "Happy Wheels".[102] Since 2006, music direction has been handled by Frankie Blue and John Hoke.[92] Themes they have written for the show include a remix of "Happy Wheels" and an original rock-based composition.[102]

In addition to "Changing Keys", Griffin also composed various incidental music cues for the syndicated version which were used for announcements of prizes in the show's early years. Among them were "Frisco Disco" (earlier the closing theme for a revival of Jeopardy! which aired in 1978 and 1979),[103] "A Time for Tony" (whose basic melody evolved into "Think!", the longtime theme song for Jeopardy![104]), "Buzzword" (later used as the theme for Merv Griffin's Crosswords), "Nightwalk", "Struttin' on Sunset", and an untitled vacation cue.[102]

Audition process

Anyone at least 18 years old has the potential to become a contestant through Wheel of Fortune's audition process. Exceptions include employees and immediate family members of ViacomCBS, Sony Pictures Entertainment, or any of their respective affiliates or subsidiaries; any firm involved in supplying prizes for the show; and television stations that broadcast Wheel and/or Jeopardy!, their sister radio stations, and those advertising agencies that are affiliated with them. Also ineligible to apply as contestants are individuals who have appeared on a different game show within the previous year, three other game shows within the past ten years, or on any version of Wheel of Fortune itself.[105]

Throughout the year, the show uses a custom-designed Winnebago recreational vehicle called the "Wheelmobile" to travel across the United States, holding open auditions at various public venues. Participants are provided with entry forms which are then drawn randomly. Individuals whose names are drawn appear on stage, five at a time, and are interviewed by traveling host Marty Lublin. The group of five then plays a mock version of the speed-up round, and five more names are selected after a puzzle is solved. Everyone who is called onstage receives a themed prize, usually determined by the spin of a miniature wheel. Auditions typically last two days, with three one-hour segments per day.[106] After each Wheelmobile event, the "most promising candidates" are invited back to the city in which the first audition was held, to participate in a second audition. Alternatively, a participant may submit an audition form with a self-shot video through the show's website to enter an audition. Contestants not appearing on stage at Wheelmobile events have their applications retained and get drawn at random to fill second-level audition vacancies. At the second audition, potential contestants play more mock games featuring a miniature wheel and puzzle board, followed by a 16-puzzle test with some letters revealed. The contestants have five minutes to solve as many puzzles as they can by writing in the correct letters. The people who pass continue the audition, playing more mock games which are followed by interviews.[107][108]

Broadcast history

Wheel of Fortune premiered on January 6, 1975, at 10:30 am (9:30 Central) on NBC. Lin Bolen, then the head of daytime programming, purchased the show from Griffin to compensate him for canceling the original Jeopardy! series, which had one year remaining on its contract. Jeopardy! aired its final episode on the Friday before Wheel's premiere. The original Wheel aired on NBC, in varying time slots between 10:30 am and noon, until June 30, 1989. Throughout that version's run, episodes were generally 30 minutes in length, except for six weeks of shows aired between December 1975 and January 1976 which were 60 minutes in length. NBC announced the cancellation of the show in August 1980, but it stayed on the air following a decision to cut the duration of The David Letterman Show from 90 to 60 minutes.[69] The network Wheel moved to CBS on July 17, 1989, and remained there until January 14, 1991.[10] After that, it briefly returned to NBC, replacing Let's Make a Deal,[109] but was canceled permanently on September 20 of that year.[10]

The daily syndicated version of Wheel premiered on September 19, 1983, preceded by a series of episodes taped on location at the Ohio State Fair and aired on WBNS-TV in Columbus, Ohio.[110] From its debut, the syndicated version offered a larger prize budget than its network counterpart.[46] The show came from humble beginnings: King World chairmen Roger, Michael, and Robert King could initially find only 50 stations that were willing to carry the show, and since they could not find affiliates for the syndicated Wheel in New York, Los Angeles, or Chicago, Philadelphia was the largest market in which the show could succeed in its early days. Only nine stations carried the show from its beginning,[111] but by midseason it was airing on all 50 of the stations that were initially willing to carry it, and by the beginning of 1984 the show was available to 99 percent of television households. Soon, Wheel succeeded Family Feud as the highest-rated syndicated show,[10] and at the beginning of the 1984–85 season, Griffin followed up on the show's success by launching a syndicated revival of Jeopardy!, hosted by Alex Trebek.[112] The syndicated success of Wheel and Jeopardy! siphoned ratings from the period's three longest-running and most popular game shows, Tic-Tac-Dough, The Joker's Wild, and Family Feud, to the point that all three series came to an end by the fall of 1986. At this point, Wheel had the highest ratings of any syndicated television series in history,[46] and at the peak of the show's popularity, over 40 million people were watching five nights per week. The series, along with companion series Jeopardy!, remained the most-watched syndicated program in the United States until dethroned by Judge Judy in 2011.[113] The program has become America's longest-running syndicated game show and its second-longest in either network or syndication, second to the version of The Price Is Right which began airing in 1972. In 1992, the show began airing on most of the owned-and-operated stations for ABC, currently known as the ABC Owned Television Stations.[114] The syndicated Wheel has become part of the consciousness of over 90 million Americans, and awarded a total of over $200 million in cash and prizes to contestants.[11]

The popularity of Wheel of Fortune has led it to become a worldwide franchise, with over forty known adaptations in international markets outside the United States.[11] Versions of the show have existed in such countries as Australia,[115] Brazil,[116] Denmark,[117] France,[118] Germany,[119] Italy,[120] Malaysia,[121] New Zealand,[122] the Philippines,[123] Poland,[124] Russia,[125] Spain,[126] the United Kingdom, and Vietnam.[127] The American version of Wheel has honored its international variants with an occasional theme of special weeks known as "Wheel Around the World", the inaugural episode of which aired when the 23rd syndicated season premiered on September 12, 2005.[128]

Between September 1997 and January 1998, CBS and Game Show Network concurrently aired a special children's version of the show titled Wheel 2000. It was hosted by David Sidoni, with Tanika Ray providing voice and motion capture for a virtual reality hostess named "Cyber Lucy".[129] Created by Scott Sternberg,[129] the spin-off featured special gameplay in which numerous rules were changed. For example, the show's child contestants competed for points and prizes instead of cash, with the eventual winner playing for a grand prize in the bonus round.[130]

Reception

Wheel of Fortune has long been one of the highest-rated programs on U.S. syndicated television. It was the highest-rated show in all of syndication before it was dethroned by Two and a Half Men in the 28th season (2010–11).[131][132] The syndicated Wheel shared the Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Game/Audience Participation Show with Jeopardy! in 2011, and Sajak won three Daytime Emmys for Outstanding Game Show Host—in 1993, 1997, and 1998. In a 2001 issue, TV Guide ranked Wheel number 25 among the 50 Greatest Game Shows of All Time,[133] and in 2013, the magazine ranked it number 2 in its list of the 60 greatest game shows ever, second only to Jeopardy![4] In August 2006, the show was ranked number 6 on GSN's list of the 50 Greatest Game Shows.[134]

Wheel was the subject of many nominations in GSN's Game Show Awards special, which aired on June 6, 2009.[135] The show was nominated for Best Game Show, but lost to Are You Smarter Than a 5th Grader?; Sajak and White were nominated for Best Game Show Host, but lost to Deal or No Deal's Howie Mandel; and O'Donnell was considered for Best Announcer but lost to Rich Fields from The Price Is Right. One of the catchphrases uttered by contestants, "I'd like to buy a vowel", was considered for Favorite Game Show Catch Phrase, but lost to "Come on down!", the announcer's catchphrase welcoming new contestants to Price. The sound effect heard at the start of a new regular gameplay round won the award for Favorite Game Show Sound Effect. The sound heard when the wheel lands on Bankrupt was also nominated. Despite having been retired from the show for nearly a decade by that point, "Changing Keys" was nominated for Best Game Show Theme Song. However, it lost to its fellow Griffin composition, "Think!" from Jeopardy![136]

A hall of fame honoring Wheel of Fortune is part of the Sony Pictures Studios tour, and was introduced on the episode aired May 10, 2010.[137] Located in the same stage as the show's taping facility, this hall of fame features memorabilia related to Wheel's syndicated history, including retired props, classic merchandise, photographs, videos, and a special case dedicated to White's wardrobe.[138] Two years later, in 2012, the show was honored with a Ride of Fame on a double decker tour bus in New York City.[139]

Merchandise

Numerous board games based on Wheel of Fortune have been released by different toy companies. The games are all similar, incorporating a wheel, puzzle display board, play money and various accessories like Free Spin tokens. Milton Bradley released the first board game in 1975. In addition to all the supplies mentioned above, the game included 20 prize cards to simulate the "shopping" prizes of the show, with prizes ranging in value from $100 to $3,000. Two editions were released, with the only differences being the box art and the included books of puzzles. Other home versions were released by Pressman Toy Corporation, Tyco/Mattel, Parker Brothers, Endless Games, and Irwin Toys.[140]

Additionally, several video games based on the show have been released for personal computers, the Internet, and various gaming consoles spanning multiple hardware generations. Most games released in the 20th century were published by GameTek, which produced a dozen Wheel games on various platforms, starting with a Nintendo Entertainment System game released in 1987 and continuing until the company closed in 1998 after filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.[141] Subsequent games were published by Hasbro Interactive and its acquirer Infogrames/Atari; Sony Online Entertainment, THQ and Ubisoft.[142]

Wheel has also been licensed to International Game Technology for use in its slot machines. The games are all loosely based on the show, with contestants given the chance to spin the wheel to win a jackpot prize. Since 1996, over 200 slot games based on the show have been created, both for real-world casinos and those on the Internet. With over 1,000 wins awarded in excess of $1,000,000 and over $3 billion in jackpots delivered, Wheel has been regarded as the most successful slots brand of all time.[143]

Notes

- The simplified title is often used by host Pat Sajak on-air and has been used instead of the full title in numerous promotional materials for the show.

- If a contestant cannot spin the wheel due to a physical limitation or disability, he/she is accompanied by a "designated spinner," a friend or family member who spins for him/her but is otherwise not involved in the game.[12]

- Sajak: "I'll give the wheel a final spin, and ask you to give me a letter. If it's in the puzzle, you have three seconds to solve it. Vowels are worth nothing, consonants are worth...[wedge amount], we'll add $1,000 to that, [dollar amount] apiece."

- The jackpot wedge was originally in round 3,[30] was moved to round 2 at the start of the 18th syndicated season in 2000,[24] and after that moved to round 1 from 2009 to 2013.[31]

References

Footnotes

- "Wheel of Fortune: Pat Sajak and Vanna White on retirement, gaffes, their 7,000th show". Wheel of Fortune. Season 36. Episode 7000. May 10, 2019. Syndicated. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

'It’s our 7,000th show,' Sajak says to applause at the start of Friday's milestone episode.

- "Harry Friedman Named Producer of 'Wheel of Fortune'" (Press release). PR Newswire. June 14, 1995 – via HighBeam Research.

- "'Wheel of Fortune' Ups Bonus Round Jackpot to $1M". TV Guide. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- Fretts, Bruce (June 17, 2013). "Eyes on the Prize". TV Guide. pp. 14–15.

- Season Premiere Tomorrow! Wheel of Fortune on YouTube

- Nemetz, Dave; Nemetz, Dave (July 29, 2020). "Jeopardy!, Wheel of Fortune to Resume Production With New Precautions". TVLine. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- https://deadline.com/2020/07/wheel-of-fortune-jeopardy-head-back-to-studio-1202997931/

- Griffin & Bender 2007, p. 100

- Ali, Rasha (June 7, 2016). "Watch 'Wheel of Fortune' Unveil a New Puzzle Format". The Wrap. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- Schwartz, Ryan & Wostbrock 1999, pp. 250–252

- "History & Fun Facts". Wheel of Fortune. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- Wheel of Fortune. Season 33. May 31, 2016. Syndication.

- Newcomb 2004, p. 2527

- "'Wheel of Fortune': About the Show". CBS Press Express. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- Wheel of Fortune. Season 33. May 25, 2016. Syndication.

- "COMING THIS FALL ON WHEEL OF FORTUNE ONE SPIN ONE SOLVE ONE MILLION DOLLARS". wheeloffortune.com. July 7, 2008. Archived from the original on September 28, 2008.

- "Watch Now: Wheel's 1st Million Dollar Winner". Philadelphia: WPVI-TV. October 15, 2008. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- "California woman becomes 2nd million dollar winner on Wheel of Fortune". Tuscaloosa, AL: WCFT-TV. May 30, 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- "Silver Spring math teacher, Sarah Manchester, wins $1 million on 'Wheel Of Fortune'". Washington, DC: WJLA-TV. September 17, 2014.

- "Celebrating 30, Episode 4". Wheel of Fortune. Season 30. Episode 5834. May 30, 2013. Syndicated. Closing credits: "Contestants are advised prior to taping that they may elect to receive the million dollar prize paid over 20 years or as a present value lump sum payment."

- Sams & Shook 1987, p. 41

- Kubasik, Ben (September 26, 1987). "TV Spots". Newsday. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- "NBC Daytime 1st Finale". Wheel of Fortune. June 30, 1989. NBC.

- "Season 18, Episode 1". Wheel of Fortune. Season 18. September 4, 2000. Syndicated.

- Sams & Shook 1987, p. 33

- "WOF 1986 Mike Jill Dawn". Wheel of Fortune. November 13, 1986. NBC.

- Sams & Shook 1987, p. 34

- Poniewozik, James (September 9, 2009). "'Wheel of Fortune' Kills Free Spin: Is Nothing Sacred?". Time. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- "Episode 2546". Wheel of Fortune. Season 14. October 22, 2001. Syndicated.

- "Season 14, Episode 11". Wheel of Fortune. Season 14. September 16, 1996. Syndicated.

- "Season 27, Episode 1". Wheel of Fortune. Season 27. September 14, 2009. Syndicated.

- "Season 7, Episode 1". Wheel of Fortune. Season 7. September 4, 1989. Syndicated.

- "Season 16, Episode 15". Wheel of Fortune. Season 16. September 21, 1998. Syndicated.

- "April 7, 1978". Wheel of Fortune. April 7, 1978. NBC.

- "Super Wheel bonus round". Kenosha News. March 8, 1980. p. 11. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- Sams & Shook 1987, pp. 40–41

- "Episode 996". Wheel of Fortune. Season 6. October 3, 1988. Syndicated.

- "Desert Southwest Week, Episode 1". Wheel of Fortune. Season 19. September 3, 2001. Syndicated.

- "Big Money Week, Episode 1". Wheel of Fortune. Season 19. October 22, 2001. Syndicated.

- Griffin & Bender 2007, pp. 99–100

- "Meet the 'Wheel'". The Chicago Tribune. March 6, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- Graham 1988, p. 183

- Stafford 2011, p. 194

- Trebek & Barsocchini 1990, p. 9

- "Wheel of Fortune". The E! True Hollywood Story. 2004.

- Terry, Clifford (May 23, 1986). "'Wheel of Fortune' long ago spun its way to the top". St. Petersburg Evening-Independent. p. 5B. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- Griffin & Bender 2007, p. 101

- "No title". Weekly Variety: 80. September 7, 1977.

- "2 to substitute for Susan Stafford". Youngstown Vindicator. May 22, 1979. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- "Vanna White biography". Biography.com. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- "No title". Observer-Reporter. August 14, 2007. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- "Vanna White Celebrates 30 Years on "Wheel of Fortune"". Katie. April 30, 2013. Syndicated.

- Greene, Bob (January 8, 1986). "Here comes Vanna White". The Free-Lance Star. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- "Vanna White takes time off from 'Wheel of Fortune'". The Greenville News. June 1, 1986. p. 9. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- "Stargazing". The Kansas City Star. March 11, 1991. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- Speers, W. (March 6, 1991). "Dog Bites Queen, And That's News". The Inquirer. Philadelphia. Associated Press, Reuters. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- "Sajak Reveals Reason for 1-Day Job Switch With Vanna White". Good Morning America. ABC. April 26, 2013.

- "Episode 2594". Wheel of Fortune. Season 14. Episode 2594. November 21, 1996. Syndication.

- "Episode 2662". Wheel of Fortune. March 4, 1997. Syndicated.

- Encyclopedia of Observances, Holidays, and Celebrations. MobileReference. 2007. ISBN 978-1-60-501177-6.

- "April Fool's Day Special". Wheel of Fortune. April 1, 1997. Syndicated.

- Grosvenor, Carrie (January 4, 2011). "Want to be Vanna for a day?". About.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- Gehring, Lydia (February 23, 2011). "Triway High School grad voted Vanna for a Day". The Daily Record. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- Amir Vera (November 8, 2019). "Vanna White hosts 'Wheel of Fortune' as Pat Sajak undergoes emergency surgery". CNN. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- Salam, Maya (December 9, 2019). "Vanna White Takes a Spin as 'Wheel of Fortune' Host After 37 Years". The New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- "Maggie Sajak Introduced as the Special Guest Letter-Turner for Weekend Getaways". YouTube. January 6, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- Caitlin O'Kane (January 7, 2020). "Pat Sajak's daughter turns letters on "Wheel of Fortune" as Vanna White takes over hosting duties". CBS News. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- Shawn M. Carter (January 7, 2020). "'Wheel of Fortune': Pat Sajak's daughter fills in for dad". Fox Business. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- West, Randy. "Charlie O'Donnell Tribute". Randy West official website. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- "Jack Clark, announcer on TV's 'Wheel of Fortune'". The Miami Herald. July 27, 1988. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- Graham, Jefferson (September 20, 1988). "'Wheel' takes a turn to new twists for fall". USA Today. p. 3D. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- Lycan, Gary (November 1, 2010). "'Wheel of Fortune' announcer Charlie O'Donnell dies at 78". The Orange County Register. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- "Veteran Announcer Jim Thornton is the New Voice of 'Wheel of Fortune'". Wheel of Fortune. June 13, 2011. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- End credits lists from appropriate Wheel of Fortune episodes.

- Albiniak, Paige (August 1, 2019). "Harry Friedman, EP of 'Wheel of Fortune' and 'Jeopardy!,' to Step Down in 2020". Broadcasting & Cable.

- Petski, Denise (August 29, 2019). "Mike Richards To Executive Produce 'Jeopardy!' & 'Wheel Of Fortune' When Harry Friedman Exits Next Year". Deadline. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- Barnes, Mike (July 25, 2013). "'Wheel of Fortune' Director Mark Corwin Dies at 65". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- "Episode 5851". Wheel of Fortune. Season 31. Episode 5851. September 16, 2013. Syndication.

- "Episode 5866". Wheel of Fortune. Season 31. Episode 5866. October 7, 2013. Syndication.

- "Episode 5891". Wheel of Fortune. Season 31. Episode 5891. November 11, 2013. Syndication.

- Barnes, Mike (November 19, 2013). "Bob Cisneros Named Director of 'Wheel of Fortune'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- "Episode 6066". Wheel of Fortune. Season 32. Episode 6066. October 13, 2014. Syndication.

- "Episode 6091". Wheel of Fortune. Season 32. Episode 6091. November 17, 2014. Syndication.

- "WHEEL OF FORTUNE NAMES ROBERT ENNIS DIRECTOR". Wheel of Fortune. September 14, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- Gilbert, Tom (August 19, 2007). "'Wheel of Fortune', 'Jeopardy!': Merv Griffin's True TV Legacy". TVWeek. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013.

- Holl, John (August 14, 2007). "To Califon, Merv was just a regular farm guy". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

Viewers who pay careful attention to the closing credits on 'Wheel of Fortune' will see the game show is produced by Califon Productions, a subtle nod from Merv Griffin, the program's creator, to the Hunterdon County community where he once owned a farm.

- "Pat, Vanna and Alex Play On!". Sony Pictures Television. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- "Inside 'Wheel of Fortune': Why Pat and Vanna Have a 'W-NN-R'". TV Guide. 1987. p. 148.

- "Shows–CBS Television City". Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- "'Wheel of Fortune', America's Favorite Game Show, Spins Into Its 20th Season". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. September 17, 1995. p. G5. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- Walker, Joseph (July 26, 1988). "'Wheel of Fortune's' other blonde". Saturday Morning Deseret News. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- "Production credits". Wheel of Fortune. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- Slotnik, Daniel E. (July 21, 2011). "Ed Flesh, Designed the Wheel of Fortune, Dies at 79". The New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- "Ed Flesh, Designer of the Wheel on 'Wheel of Fortune,' Dies at 79". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- "'Spin the Wheel' EP Says 'Knowledge, Strategy & Luck' Could Win Players $23M". TV Insider. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- "'Wheel' gets modern board". The Vindicator. February 25, 1997. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- "Featured Contestant: Dana C." Wheel of Fortune. March 11, 2013. Archived from the original on March 20, 2014. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "Featured Contestant: Seth N." Wheel of Fortune. December 18, 2013. Archived from the original on March 20, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- Teti, John (March 20, 2014). "Watch the most amazing solve in 'Wheel of Fortune' history". The A.V. Club. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- Jeffries, David. "Merv Griffin biography". Allmusic. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- Morin, Monte (December 17, 2003). "Pilot Killed in Crash Was TV, Film Composer; Steve Kaplan, who died when his plane crashed into a Claremont home, had written music for 'Jeopardy!' and 'Wheel of Fortune.'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- "'Wheel of Fortune' soundtrack". Ringostrack.com. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- "Merv Griffin soundtrack". Ringostrack.com. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- Bickelhaupt, Susan (September 5, 1989). "Placing himself in 'Jeopardy!' tonight". The Boston Globe. p. 54.

- "Be a Contestant". Wheel of Fortune. Archived from the original on February 16, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "Wheelmobile Audition Tips". Portland, OR: KATU-TV. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- "Show Guide: Show FAQs". Wheel of Fortune. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- "Wheelmobile". Wheel of Fortune. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- Feder, Robert (December 26, 1990). "'Wheel of Fortune' spins back to NBC". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- "No title". Variety: 54. August 10, 1983.

- "No title". TV Guide. 32: 64. 1984.

- Griffin & Bender 2007, p. 106

- "Syndication Ratings: 'Judge Judy' Is Queen of Syndie Season". Broadcasting & Cable. September 5, 2012. Archived from the original on December 4, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- Littleton, Cynthia. "ABC Shells Out to Keep Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy After Big Offer From Fox". Variety. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- "'Wheel of Fortune' (Australia)". Australian Game Show Homepage. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "'SBT – Roda a Roda Jequiti'". Official SBT Website. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Liebst, Asger (2009). "Opfindelsen af Lykkehjulet". Reklamens århundrede: 1901–2001, billeder fra danskernes hverdrag. Nordisk Forlag A/S. p. 138. ISBN 978-87-02-08311-8.

- "La Roue de la Fortune" (in French). Émission TV. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "Glücksrad" (in German). fernsehserien.de. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "La WEB Ruota della Fortuna". GiocaItalia.it. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- Yeoh Seng Guan (2011). Media, Culture and Society in Malaysia. Routledge. pp. 29, 31, 35. ISBN 0203861655.

- "What Goes Around: The Wheel of Fortune Returns". Stuff.co.nz. April 13, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- Dimaculangan, Jocelyn (January 13, 2008). "Philippine version of 'Wheel of Fortune' premieres on January 14". Philippine Entertainment Portal. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "Koło Fortuny: Rules of Polish 'Wheel of Fortune'". Casino Observer. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "Pole Chudes, or The Russian 'Wheel of Fortune'". Wheel-Roulette.net. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "La ruleta de la suerte" (in Spanish). Laguia TV. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "'Wheel of Fortune'". UKGameShows.com. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "Wheel Around the World Inaugural Week, Episode 1". Wheel of Fortune. Season 23. September 12, 2005. Syndicated.

- "Popular game show takes kids for a spin". Austin American-Statesman. p. 11. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- Schwartz, Ryan & Wostbrock 1999, p. 252

- "U.S. television ratings: top 10 syndicated programs in season 2009/10: Statistic". Statista.com. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- "2010–11 Report: 'Two and a Half Men' Still Strong; Network Ratings Still Sliding". The Wrap TV. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- "'TV Guide' Names the 50 Greatest Game Shows of All Time". Hall of Game Show Fame.

- The 50 Greatest Game Shows of All Time. GSN. Retrieved on August 31, 2006.

- Catlin, Roger. "On Tonight: First Game Show Awards". TV Eye. Archived from the original on June 23, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- "Title Unknown". Archived from the original on June 23, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- "State Fair Week, Episode 1". Wheel of Fortune. Season 27. May 10, 2010. Syndicated.

- Glaus, Heidi (November 10, 2011). "Tour the 'Wheel of Fortune' Hall of Fame". St. Louis, MO: KSDK-TV. Archived from the original on October 3, 2014. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- Wheel Of Fortune Honored By Gray Line New York's Ride Of Fame Getty Images. May 23, 2012.

- "Wheel of Fortune board games". Board Game Geek. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- "GameTek Games". IGN. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- "'Wheel of Fortune' Licensees". MobyGames. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- "Wheel of Fortune at IGT Games". International Game Technology. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

Works cited

- Graham, Jefferson (1988). Come on Down!!!: The Game Show Book. New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 0-89659-794-6.

- Griffin, Merv & Bender, David (2007). Merv: Making the Good Life Last. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7434-5696-3.

- Newcomb, Horace (2004). Encyclopedia of Television (2nd ed.). New York: Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 1-57958-411-X – via Google Books.

- Sams, David R. & Shook, Robert L. (1987). Wheel of Fortune. New York: St. Martins Press. ISBN 0-312-90833-4.

- Schwartz, David; Ryan, Steve & Wostbrock, Fred (1999). The Encyclopedia of TV Game Shows (3rd ed.). New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-3846-5.

- Stafford, Susan (2011). Stop the Wheel, I Want to Get Off! (eBook). Xlibris. ISBN 978-1-4568-7438-4 – via Google Books.

- Trebek, Alex & Barsocchini, Peter (1990). The 'Jeopardy!' Book: The Answers, the Questions, the Facts, and the Stories of the Greatest Game Show in History. Introduction by Merv Griffin. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-096511-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wheel of Fortune (U.S. game show). |