South Atlantic tropical cyclone

South Atlantic tropical cyclones are unusual weather events that occur in the Southern Hemisphere. Strong wind shear, which disrupts the formation of cyclones, as well as a lack of weather disturbances favorable for development in the South Atlantic Ocean, make any strong tropical system extremely rare, and Hurricane Catarina in 2004 is the only recorded South Atlantic hurricane in history. South Atlantic storms have developed year-round, with activity peaking during the months from November through May in this basin. Since 2011, the Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center has assigned names to tropical and subtropical systems in the western side of the basin, near the eastern coast of Brazil, when they have sustained wind speeds of at least 65 km/h (40 mph), the generally accepted minimum sustained wind speed for a disturbance to be designated as a tropical storm in the North Atlantic basin. Below is a list of notable South Atlantic tropical and subtropical cyclones.

Theories concerning infrequency of occurrence

It was initially thought that tropical cyclones did not develop within the South Atlantic.[1] Very strong vertical wind shear in the troposphere is considered a deterrent.[2] The Intertropical Convergence Zone drops one to two degrees south of the equator,[3] not far enough from the equator for the Coriolis force to significantly aid development. Water temperatures in the tropics of the southern Atlantic are cooler than those in the tropical north Atlantic.[4]

During April 1991, these assertions were proven false, when the United States' National Hurricane Center (NHC) reported that a tropical cyclone had developed over the Eastern South Atlantic.[1][5] In subsequent years, a few systems were suspected to have the characteristics needed to be classified as a tropical cyclone, including in March 1994 and January 2004.[6][7] During March 2004, an extratropical cyclone formally transitioned into a tropical cyclone and made landfall on Brazil, after becoming a Category 2 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale. While the system was threatening the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina, a newspaper used the headline "Furacão Catarina," which was originally presumed to mean "furacão (hurricane) threatening (Santa) Catarina (the state)".[1] After international presses started monitoring the system, "Hurricane Catarina" has formally been adopted.

At the Sixth WMO International Workshop on Tropical Cyclones (IWTC-VI) in 2006, it was questioned if any subtropical or tropical cyclones had developed within the South Atlantic before Catarina.[7] It was noted that suspect systems had developed in January 1970, March 1994, January 2004, March 2004, May 2004, February 2006, and March 2006.[7] It was also suggested that an effort should be made to locate any possible systems using satellite imagery and synoptic data; however, it was noted that this effort may be hindered by the lack of any geostationary imagery over the basin before 1966.[7] A study was subsequently performed and published during 2012, which concluded that there had been 63 subtropical cyclones in the Southern Atlantic between 1957 and 2007.[8] During January 2009, a subtropical storm developed in the basin, and in March 2010, a tropical storm developed, which was named Anita by the Brazilian public and private weather services.[9][10] In 2011, the Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center started to assign names to tropical and subtropical cyclones that develop within its area of responsibility, to the west of 20°W, when they have sustained wind speeds of at least 65 km/h (40 mph).[11]

Known storms and impacts

Pre-2010s

1991 Angola tropical storm

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | April 10, 1991 – April 14, 1991 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (1-min) |

A low pressure area formed over the Congo Basin on April 9. The next day it moved offshore northern Angola with a curved cloud pattern. It moved westward over an area of warm waters while the circulation became better defined. According to the United States National Hurricane Center, the system was probably either a tropical depression or a tropical storm at its peak intensity. On April 14, the system rapidly dissipated, as it was absorbed into a large squall line.[12][13] This is the only recorded tropical cyclone in the eastern South Atlantic.

Hurricane Catarina

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 24, 2004 – March 28, 2004 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 km/h (100 mph) (1-min) 972 hPa (mbar) |

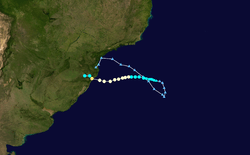

Hurricane Catarina was an extraordinarily rare hurricane-strength tropical cyclone, forming in the southern Atlantic Ocean in March 2004.[14] Just after becoming a hurricane, it hit the southern coast of Brazil in the state of Santa Catarina on the evening of March 28, with winds estimated near 155 km/h (96 mph), making it a Category 2-equivalent on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. The cyclone killed 3 to 10 people and caused millions of dollars in damage in Brazil.

At the time, the Brazilians were taken completely by surprise, and were initially skeptical that an actual tropical cyclone could have formed in the South Atlantic. Eventually, however, they were convinced, and adopted the previously unofficial name "Catarina" for the storm, after Santa Catarina state. This event is considered by some meteorologists to be a nearly once-in-a-lifetime occurrence.

2010s

Tropical Storm Anita

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 8, 2010 – March 12, 2010 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (1-min) 995 hPa (mbar) |

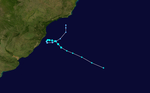

On March 8, 2010, a previously extratropical cyclone developed tropical characteristics and was classified as a subtropical cyclone off the coast of southern Brazil. The following day, the United States Naval Research Laboratory began monitoring the system as a system of interest under the designation of 90Q. The National Hurricane Center also began monitoring the system as Low SL90. During the afternoon of March 9, the system had attained an intensity of 55 km/h (34 mph) and a barometric pressure of 1000 hPa (mbar). It was declared a tropical storm on March 10 and became extratropical late on March 12.[15] Anita's accumulated cyclone energy was estimated at 2.0525 by the Florida State University. There was no damage associated to the storm, except high sea in the coasts of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina. Post mortem, the cyclone was given the name "Anita" by private and public weather centers in Southern Brazil.[16]

Subtropical Storm Arani

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 14, 2011 – March 16, 2011 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (1-min) 989 hPa (mbar) |

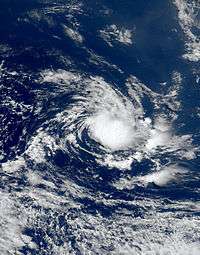

Early on March 14, 2011, the Navy Hydrographic Center-Brazilian Navy (SMM), in coordination with the National Institute of Meteorology, were monitoring an organizing area of convection near the southeast coast of Brazil.[17] Later that day a low pressure area developed just east of Vitória, Espírito Santo,[18] and by 12:00 UTC, the system organized into a subtropical depression, located about 140 km (87 mi) east of Campos dos Goytacazes.[19] Guided by a trough and a weak ridge to its north, the system moved slowly southeastward over an area of warm waters,[20][21] intensifying into Subtropical Cyclone Arani on March 15,[22] as named by the Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center. The storm was classified as subtropical, as the convection was east of the center. On March 16, Arani began experiencing 25 kn (13 m/s; 46 km/h; 29 mph) of wind shear because another frontal system bumped it from behind.[24]

Before it developed into a subtropical cyclone, Arani produced torrential rains over portions of southeastern Brazil, resulting in flash flooding and landslides. Significant damage was reported in portions of Espírito Santo, though specifics are unknown.[25] Increased swells along the coast prompted ocean travel warnings.[26]

Subtropical Storm Bapo

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 5, 2015 – February 8, 2015 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (1-min) 992 hPa (mbar) |

On February 5, 2015, a subtropical depression developed about 105 nautical miles (195 km; 120 mi) to the southeast of São Paulo, Brazil.[27] During the next day, low-level baroclincity decreased around the system, as it moved southeastwards away from the Brazilian coast and intensified further.[28] The system was named Bapo by the Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center during February 6, after it had intensified into a subtropical storm.[29][30] Over the next couple of days the system continued to move south-eastwards before it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone during February 8.[31]

Subtropical Storm Cari

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 10, 2015 – March 13, 2015 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (1-min) 998 hPa (mbar) |

On March 10, 2015, the Hydrographic Center of the Brazilian Navy began issuing warnings on Subtropical Depression 3 during early afternoon,[32] while the Center for Weather Forecast and Climatic Studies (CPTEC in Portuguese) already assigned the name Cari for the storm.[33] At 00:00 UTC on March 11, the Hydrographic Center of the Brazilian Navy upgraded Cari to a subtropical storm, also assigning a name to it.[34] On March 12, the Brazilian Hydrographic Center downgraded Cari to a subtropical depression,[35] while the CPTEC stated that the storm had become a "Hybrid cyclone".[36] During early afternoon of March 13, the Brazilian Navy declared that Cari became a remnant low.[37]

Cari brought heavy rainfall, flooding and landslides to eastern cities of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul states.[38] Rain totals from 100 to 180 mm (3.9 to 7.1 in) were observed associated with the storms and wind topped 75 km/h (47 mph) in Cabo de Santa Marta.[38] A Navy buoy registered a 6-metre (20 ft) wave off the coast of Santa Catarina.[38]

Subtropical Storm Deni

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 15, 2016 – November 16, 2016 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 km/h (45 mph) (1-min) 998 hPa (mbar) |

A subtropical depression formed southwest of Rio de Janeiro on November 15, 2016.[39] It intensified into a subtropical storm and received the name Deni on November 16.[40] Moving south-southeastwards, Deni soon became extratropical shortly before 00:00 UTC on November 17.[41]

Subtropical Storm Eçaí

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 4, 2016 – December 6, 2016 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 km/h (65 mph) (1-min) 992 hPa (mbar) |

An extratropical cyclone entered the South Atlantic Ocean from Santa Catarina early on December 4, 2016.[42] Later, it intensified quickly and then transitioned into a subtropical storm shortly before 22:00 BRST (00:00 UTC on December 5), with the name Eçaí assigned by the Hydrographic Center of the Brazilian Navy.[43] Eçaí started to decay on December 5, and weakened into a subtropical depression at around 00:00 UTC on December 6.[44]

Subtropical Storm Guará

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 9, 2017 – December 11, 2017 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 km/h (45 mph) (1-min) 996 hPa (mbar) |

According to the Hydrographic Center of the Brazilian Navy, on December 9, 2017, a subtropical storm formed over the southeastern tip of a South Atlantic Convergence Zone, being located close to the state border between Espírito Santo and Bahia, moving southeastwards away from land.[45][46][47] On early December 11, as it moved more southwardly, Guará attained its peak intensity while transitioning to an extratropical cyclone.[48] Shortly thereafter, Guará became fully extratropical, later on the same day.[49]

Tropical Storm Iba

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 23, 2019 – March 28, 2019 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (55 mph) (1-min) 1006 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical depression formed within a monsoon trough on March 23, 2019, off the coast of Bahia.[50][51] On the next day, the system intensified into a tropical storm, receiving the name Iba from the Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center. After moving southwestward for a couple of days, on March 26, Iba turned southeastward. Afterward, the storm began to weaken due to strong wind shear. On March 27, Iba weakened into a tropical depression and turned to the east, before dissipating on March 28.

Iba was the first tropical storm to develop in the basin since Anita in 2010, as well as the first fully tropical system to be named from the Brazilian naming list.[52]

Subtropical Storm Jaguar

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 20, 2019 – May 22, 2019 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (1-min) 1010 hPa (mbar) |

On May 20, 2019, a subtropical depression formed east of Rio de Janeiro. Later that day, the system strengthened into a subtropical storm, receiving the name Jaguar from the Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center.[53] However, the system did not intensify any further, as it soon encountered unfavorable conditions, and Jaguar eventually dissipated on May 22.

2020s

Subtropical Storm Kurumí

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 23, 2020 – January 25, 2020 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (1-min) 998 hPa (mbar) |

On January 21, 2020, the Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center began to monitor an area of persisting thunderstorms near São Paulo for potential subtropical cyclone development. Generally tracking southeastward, the system began to organize within the afternoon hours of January 22 and was designated a subtropical depression in the early hours of January 23. Several hours later, due to a lack of wind shear, the system intensified into a subtropical storm and was given the name Kurumí.[54] After this bout of intensification, Kurumí moved southward and began to succumb to much more unfavorable conditions. It weakened back to a subtropical depression on January 25, while also beginning to merge with a large extratropical low to its south.[55] The last advisory was issued on Kurumí later that same day.

The front associated with Kurumí later played a role in the 2020 Brazilian floods and mudslides, dragging behind it heavy rainfall. Over 171.8 mm (6.76 in) of rain fell in the Belo Horizonte metro area on January 24, triggering a landslide and killing 3 people and leaving 1 missing.[56]

Other systems

Pre-2004

According to a presentation at the Sixth WMO International Workshop on Tropical Cyclones (IWTC-VI), satellite imagery from January 1970 showed that a system with an eyewall had developed behind a cold front and that the system needed further analysis to determine if it was tropical or subtropical.[7] On March 27, 1974, a weak area of low pressure that had originated over the Amazon River started to intensify further.[57] Over the next 48 hours the system quickly developed further and was classified as subtropical, as it developed a banding structure and deep convection near its warm core.[57] On March 29, a north-westerly flow encroached on the systems environment, which caused the system to rapidly move towards 40S and the cold waters that were present to the south of 40°S.[57] In March 1994, a system that was thought to be weaker than Catarina was spawned but was located over cool and open waters.[58]

2004–2009

During 2004, the large-scale conditions over the South Atlantic were more conducive than usual for subtropical or tropical systems, with 4 systems noted.[7] The first possible tropical cyclone developed within a trough of low pressure, to the southeast of Salvador, Brazil on January 18.[6][7] The system subsequently displayed a small central dense overcast (CDO) and was suspected to be at the peak of its development as either a tropical depression or a tropical storm during the next day.[6] The system was subsequently affected by some strong shear, before it moved inland and weakened along the coast of Brazil before it was last noted during January 21.[6] Within Brazil the system caused heavy rain and flooding with a state of emergency declared in Aracaju, after the river overflowed and burst its banks which flooded homes, destroyed crops and caused parts of the highway to collapse.[6] However, it was noted that not all of the heavy rain and impacts were attributable to the system, as a large monsoon low covered much of Brazil at the time.[6] The second system was a possible hybrid cyclone that developed near south-eastern Brazil between March 15–16.[7] Hurricane Catarina was the third system, while the fourth system had a well-defined eye like structure, and formed off the coast of Brazil on March 15, 2004.[7]

On February 22, 2006, a baroclinic cyclone intensified quickly and was estimated to have peaked with 1-minute sustained wind speeds of 105 km/h (65 mph), after radar data showed that the system had developed an eye and banding.[7] However, there were questions about how tropical the system was, as it did not separate from the westerlies or the baroclinic zone it was in.[7][59] Between March 11–17, 2006, another system with a warm core developed and moved southward along the South Atlantic Zone, before dissipating.[7]

Two subtropical cyclones affected both Uruguay and Rio Grande do Sul state in Brazil between 2009 and 2010. On January 28, 2009, a cold-core mid to upper-level trough in phase with a low-level warm-core low formed a system and moved eastward into the South Atlantic.[60] The storm produced rainfall in 24 hours of 300 mm (12 in) or more in some locations of Rocha (Uruguay) and southern Rio Grande do Sul. The weather station owned by MetSul Weather Center in Morro Redondo, Southern Brazil, recorded 278.2 mm (10.95 in) in a 24-hour period. The storm caused fourteen deaths and the evacuation of thousands, with an emergency declared in four cities.[9] It lasted until February 1, when the cyclone became extratropical.[61]

2010–2016

On November 16, 2010, a cold-core mid to upper-level trough in phase with a low-level warm-core low developed a low-pressure system over Brazil, and moved southeastward into the South Atlantic, where it slightly deepened.[62] The system brought locally heavy rains in southern Brazil and northeast of Uruguay that exceeded 200 millimeters within a few hours, in some locations of Southern Rio Grande do Sul, northwest of Pelotas.[63] Damages and flooding were observed in Cerrito, São Lourenço do Sul and Pedro Osório.[63] Bañado de Pajas, departament of Cerro Largo in Uruguay, recorded 240 mm (9.4 in) of rain.[63] The subtropical cyclone then became a weak trough on November 19, according to the CPTEC.[64]

Between December 23, 2013 and January 24, 2015, the CPTEC and Navy Hydrography Center monitored four subtropical depressions to the south of Rio de Janeiro. The first one lasted until Christmas Day, 2013.[65][66][67][68] Two subtropical depressions formed in 2014: one in late-February 2014 and the other in late-March 2014.[69][70][71] A fourth one formed in late January 2015.[72][73]

On January 5, 2016, the Hydrographic Center of the Brazilian Navy issued warnings on a subtropical depression that formed east of Vitória, Espírito Santo.[74] On the next day, the system strengthened into a tropical depression and other agencies considered it as an invest, designating it as 90Q;[75][76] however, on January 7, the tropical depression dissipated.[75][77]

Storm names

The following names are published by the Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center's Marine Meteorological Service and used for tropical and subtropical storms that form in the area west of 20ºW and south of equator in the South Atlantic Ocean. Originally announced in 2011,[11] the list has been extended from ten to fifteen names in 2018. The names are assigned in alphabetical order and used in rotating order without regard to year. The names of significant tropical or subtropical systems will be retired.[78]

|

|

|

Kamby was replaced by Kurumí in 2018 without being used.

Climatological statistics

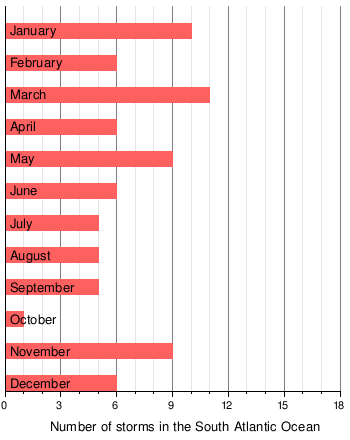

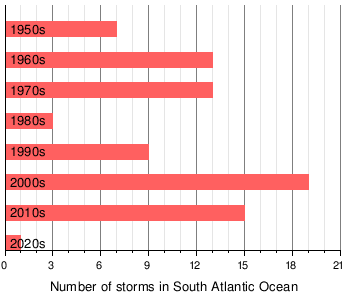

There have been over 80 recorded tropical and subtropical cyclones in the South Atlantic Ocean since 1957. Like most southern hemisphere cyclone seasons, most of the storms have formed between November and May.

List of storms, by month

|

|

List of storms, by decade

|

|

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South Atlantic tropical cyclones. |

- Unusual areas of tropical cyclone formation

- List of tropical cyclone records

- List of South America tropical cyclones

- Southern Hemisphere tropical cyclone

- Atlantic hurricane (North Atlantic tropical cyclone)

- Atlantic Equatorial mode

- Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone

- Tropical cyclone basins

- 2006 Central Pacific cyclone

- 1996 Lake Huron cyclone

- Subtropical Cyclone Katie

References

- Padgett, Gary. "Monthly Tropical Cyclone Summary March 2004". Archived from the original on December 17, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Landsea, Christopher W (July 13, 2005). "Subject: Tropical Cyclone Names: G6) Why doesn't the South Atlantic Ocean experience tropical cyclones?". Tropical Cyclone Frequently Asked Question. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on March 27, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Gordon E. Dunn & Banner I. Miller (1960). Atlantic Hurricanes. Louisiana State University Press. p. 33. ASIN B0006BM85S.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: How do tropical cyclones form?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 26, 2006.

- National Hurricane Center (1991). McAdie, Colin J; Rappaport, Edward N (eds.). II. Tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic Basin: A. Overview (Diagnostic Report of the National Hurricane Center: June and July 1991). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 10–14. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- Padgett, Gary. "Monthly Tropical Cyclone Summary January 2004". Archived from the original on December 17, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Topic 2a: The Catarina Phenomenon (PDF). The Sixth WMO International Workshop on Tropical Cyclones (IWTC-VI). San José, Costa Rica: World Meteorological Organization. 2006. pp. 329–360. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Evans, Jenny L; Braun, Aviva J (2012). "A Climatology of Subtropical Cyclones in the South Atlantic". Journal of Climate. American Meteorological Society. 25 (21): 7328–7340. Bibcode:2012JCli...25.7328E. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00212.1.

- Padgett, Gary (April 7, 2009). "January 2009 Tropical Weather Summary". Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- Padgett, Gary. "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Tracks March 2010". Archived from the original on December 17, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- "Normas Da Autoridade Marítima Para As Atividades De Meteorologia Marítima" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Brazilian Navy. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- National Hurricane Center (1991). McAdie, Colin J; Rappaport, Edward N (eds.). II. Tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic Basin: A. Overview (Diagnostic Report of the National Hurricane Center: June and July 1991). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 10, 13, 14. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- Marcel Leroux (2001). "Tropical Cyclones". The Meteorology and Climate of Tropical Africa. Praxis Publishing Ltd. p. 314. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- College of Earth & Mineral Sciences (2004). "Upper-level lows". Pennsylvania State University. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- https://www.webcitation.org/5o7vOfDzk?url=http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/discussions/fxsa20.html

- "Monitoramento - Ciclone tropical na costa gaúcha" (in Portuguese). Brazilian Meteorological Service. March 2010. Archived from the original on February 28, 2010.

- Chura, Ledesma, Davison (March 14, 2011). "South American Synopsis". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on December 24, 2010. Retrieved March 14, 2011.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chura, Ledesma, Davison (March 14, 2011). "South American Synopsis (2)". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2011.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Marine Meteorological Service (March 14, 2011). "Weather and Sea Bulletin Referent Analysis 1200 GMT - 14/MAR/2011". Brazil Navy Hydrographic Center. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- Chura, Ledesma, Davison (March 15, 2011). "South American Synopsis (3)". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2011.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chura, Ledesma, Davison (March 15, 2011). "South American Synopsis (4)". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on December 24, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2011.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Marine Meteorological Service (March 15, 2011). "Severe Weather Warnings". Brazil Navy Hydrographic Center. Archived from the original on July 9, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- Rob Gutro (March 15, 2011). "NASA's Aqua Satellite Spots Rare Southern Atlantic Sub-tropical Storm". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- Unattributed (March 16, 2011). "Arani – tempestade subtropical afasta-se da costa do ES" (in Portuguese). Climatempo. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- Unattributed (March 16, 2011). "Após formar um olho, ciclone subtropical Arani perde força nesta quarta" (in Portuguese). Jornal De Tempo. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- "Weather and Sea Bulletin Referent Analysis 1200 UTC for February 5, 2015". Marinha do Brasil - Navy Hydrographic Centre. February 5, 2015. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- https://www.webcitation.org/6WC1P8mZO?url=http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/discussions/hpcdiscussions.php?disc=fxsa21

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-08. Retrieved 2015-02-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Análise Sinótica – 06/02/2015" (PDF). CPTEC - INPE. February 6, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- "Weather and Sea Bulletin Referent Analysis 0000 UTC - 08/FEB/2015". Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center - Marine Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- "Análise Sinótica de 1200 UTC". Marinha do Brasil - Navy Hydrographic Centre. March 10, 2015. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "Análise Sinótica – 10/03/2015" (PDF). CPTEC - INPE. March 10, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "Weather and Sea Bulletin Referent Analysis 0000 UTC - 11/03/2015". Marinha do Brasil - Navy Hydrographic Centre. March 11, 2015. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "Análise Sinótica de 0000 UTC". Marinha do Brasil - Navy Hydrographic Centre. March 12, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Análise Sinótica – 12/03/2015". CPTEC - INPE. March 12, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Análise Sinótica de 1200 UTC". Marinha do Brasil - Navy Hydrographic Centre. March 13, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- "Cari é rebaixado ao enfraquecer e ciclone se afasta do continente" (in Portuguese). Metsul. March 12, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- "Weather and Sea Bulletin Issued at 1200 UTC - 15/NOV/2016". Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "Weather and Sea Bulletin Issued at 0000 UTC - 16/NOV/2016". Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center. 16 November 2016. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- "Weather and Sea Bulletin Issued at 0000 UTC - 17/NOV/2016". Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center. 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- "Sea Level Pressure Chart 0000 UTC for 4 Dec 2016" (in Portuguese). Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center. 4 December 2016. Archived from the original (JPEG) on 5 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "Weather and Sea Bulletin Issued at 0000 UTC - 05/DEC/2016". Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center. 5 December 2016. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "Weather and Sea Bulletin Issued at 0000 UTC - 06/DEC/2016". Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center. 6 December 2016. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "METEOROMARINHA REFERENTE ANALISE DE 1200 HMG – 09/DEZ/2017" (in Portuguese). Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center. December 9, 2017. Archived from the original on January 31, 2006. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- "Sea Level Pressure Chart 1200 UTC for 9 Dec 2017" (JPEG). Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center. 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Análise Sinótica – 09/12/2017" (PDF). CPTEC - INPE. 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Sea Level Pressure Chart 0000 UTC for 11 Dec 2017" (JPEG). Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center. 11 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- "Sea Level Pressure Chart 1200 UTC for 11 Dec 2017" (JPEG). Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center. 11 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- "Análise Sinótica" (in Portuguese). CPTEC. 23 March 2019. Archived from the original (GIF) on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "WARNING NR 205/2019". Marine Meteorological Service. 23 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "WARNING NR 208/2019". Marine Meteorological Service. 24 March 2019. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "WARNING NR 422/2019". Marine Meteorological Service. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "WARNINGS AND FORECASTS- SUBTROPICAL STORM KURUMI". Marine Meteorological Service. 24 Jan 2020. Retrieved 24 Jan 2020.

- "SPECIAL WARNING - SUBTROPICAL DEPRESSION "KURUMI"". Centro de Hidrografia da Marinha: MARINHA DO BRASIL. January 25, 2020. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020.

- "Heavy rains cause casualties, damage in southeast Brazilian region". Xinhua News. January 24, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- McTaggart-Cowan, Ron; Bosart, Lance; Davis, Christopher; Eyad, Atallah; Gyakum, John; Emaunel, Kerry (2006). "Analysis of Hurricane Catarina (2004)". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 134 (11): 3048–3049. Bibcode:2006MWRv..134.3029M. doi:10.1175/MWR3330.1.

- Henson, Bob (2005). "What was Catarina?". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- Padgett, Gary. "Monthly Tropical Cyclone Summary February 2006". Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- "Boletim Técnico – 30/01/2009" (in Portuguese). CPTEC - INPE. January 30, 2009. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- "Boletim Técnico – 01/02/2009" (in Portuguese). CPTEC - INPE. February 1, 2009. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- "Análise Sinótica: 17/11/2010-00Z" (in Portuguese). CPTEC - INPE. November 2010. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010.

- "Baixas começam a semana "em alta"" (in Portuguese). METSUL. November 2010. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010.

- "Boletim Technico 19/11/10 - 00z". CPTEC. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010.

- "Análise Sinótica – 23/12/2013" (PDF) (in Portuguese). CPTEC - INPE. December 23, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- "Análise Sinótica – 24/12/2013" (PDF) (in Portuguese). CPTEC - INPE. December 24, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- "SÍNTESE SINÓTICA DEZEMBRO DE 2013" (PDF) (in Portuguese). CPTEC - INPE. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- "Análise Sinótica – 25/12/2013" (PDF) (in Portuguese). CPTEC - INPE. December 25, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- "Weather and Sea Bulletin Referent Analysis 1200 UTC for 20 Feb 2014". Navy Hydrography Center/Brazilian Navy. February 20, 2014. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- "Análise Sinótica – 28/03/2014" (PDF) (in Portuguese). CPTEC - INPE. March 28, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- "Meteoromarinha referente à análise de 1200 HMG - 28/mar/2014" (in Portuguese). Navy Hydrography Center. March 28, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- "Sea Level Pressure Chart 1200 UTC for 23 Jan 2015". Marinha do Brasil - Navy Hydrographic Centre. January 23, 2015. Archived from the original on January 23, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- "Sea Level Pressure Chart 0000 UTC for 24 Jan 2015". Marinha do Brasil - Navy Hydrographic Centre. January 24, 2015. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- "Sea Level Pressure Chart 1200 UTC - 5 Jan 2016". Marinha do Brasil - Navy Hydrographic Center. Archived from the original (JPEG) on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- Could a Rare Tropical Storm Form in the South Atlantic Ocean?

- United States Naval Research Laboratory–Monterey, Marine Meteorology Division. "Invest-90Q Location File". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (dead link) - Rare January Depression in Central Pacific; Atlantic Subtropical Storm Next Week?

- "NORMAS DA AUTORIDADE MARÍTIMA PARA AS ATIVIDADES DE METEOROLOGIA MARÍTIMA NORMAM-19 1a REVISÃO" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Brazilian Navy. 2018. p. C-1-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South Atlantic tropical cyclones. |

- Brazilian Navy Hydrography Center - Marine Meteorological Service (in Portuguese)

- NOAA info on South Atlantic Tropical Cyclones

- CIMSS Satellite Blog: "Another tropical cyclone in the South Atlantic Ocean?"

- Meteogroup Weathercast: Do hurricanes form in the South Atlantic?

- Satellite animation of the 1991 Angola tropical storm

- Rosa, Marcelo Barbio; P. Satyamurty; N. J. Ferreira; L. T. Silva (2019). "A comparative study of intense surface cyclones off the coasts of southeastern Brazil and Mozambique". Int. J. Climatol. 39 (8): 3523–3542. doi:10.1002/joc.6036.