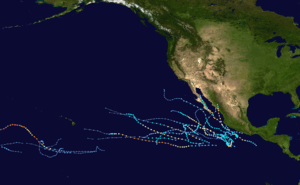

2006 Central Pacific cyclone

The 2006 Central Pacific cyclone, also known as Invest 91C or Storm 91C, was an unusual weather system that formed in 2006. Forming on October 30 from a mid-latitude cyclone in the north Pacific mid-latitudes, it moved over waters warmer than normal. The system acquired some features more typical of subtropical and even tropical cyclones. However, as it neared western North America, the system fell apart, dissipating soon after landfall, on November 4. Moisture from the storm's remnants caused substantial rainfall in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. The exact status and nature of this weather event is unknown, with meteorologists and weather agencies having differing opinions.

Part of the 2006 Pacific hurricane season (unofficially) | |

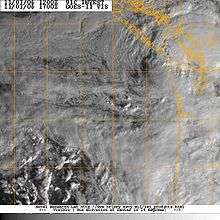

The cyclone at peak strength on November 1 | |

| Type | Tropical cyclone |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 28, 2006 |

| Dissipated | November 4, 2006 |

| Lowest pressure | 989 mb (29.21 inHg) |

| Highest winds |

|

| Damage | Minimal |

| Casualties | None reported |

| Areas affected | British Columbia, Pacific Northwest |

Meteorological history

On October 28, 2006, a cut-off extratropical cyclone over the central north Pacific moved over an area of ocean with sea surface temperatures as high as 2 °C above normal, at 16 – 18 °C (60.8 – 64.4 °F), and stalled there for two days.[1][2][3] By October 31, the system had acquired convection, a warmer-than-normal core,[1] and an eye-like feature.[3] During this time it had moved east, then northeast, and then northwest.[1] On November 1, the system reached its peak intensity, and had estimated winds of 100 km/h (60 mph) and its most developed convection. After that, it slowly weakened, looped counter-clockwise, and headed east towards the west coast of North America. This system's center of circulation passed south of observation buoy 46637 on November 1. The buoy's lowest pressure reading was 989 mbar. Other buoys indicated that a rather large area of low pressure was associated with the system. Buoy 46637 was not at the system's center of circulation, so it is possible that this system had a lower minimum pressure than was actually measured.[1] On November 2, wind shear started taking its toll, and all convection was gone by the next day, when the storm was located roughly 520 mi (840 km) off the coast of Oregon.[1] On November 3, the storm made landfall on the Olympic Peninsula in the State of Washington, bringing tropical storm-like conditions to the Pacific Northwest, including sustained winds at 40 mph and wind gusts up to 60 mph.[4][3] Following its landfall, the storm rapidly weakened and dissipated on the next day.[4]

Impact, preparation, and records

In response to the weather system, the American National Weather Service issued wind watches for the Oregon Coast.[4] The system brought heavy rain to portions of Vancouver Island.[5]

If Storm 91C is considered a tropical or subtropical cyclone, it holds several records. Since the storm is not official, its holding of these records is unofficial. Since it formed at 36°N, this system formed at the northernmost latitude of any cyclone in the eastern north Pacific basin.[6] The previous record-holder was Tropical Storm Wene, which formed at 32°N before crossing the dateline.[7][8] In addition, this system's track data indicated that it crossed from the central to the east Pacific as it formed at longitude 149°W and dissipated at 135°W.[6] Only two recorded other tropical cyclones had done this previously.[8]

Nature of the system

This system has been considered a tropical, subtropical, or extratropical cyclone.

Mark Guishard, a meteorologist with Bermuda Weather Service, was of the opinion that the system had completed tropical cyclogenesis and was a tropical cyclone. Meteorologist Mark Lander thought that cloud tops were similar to several Atlantic hurricanes, Hurricane Vince in particular.[1] James Franklin, a meteorologist at the National Hurricane Center, said:

The system was of frontal origin... the frontal structure was eventually lost.... The convective structure resembled a tropical, rather than subtropical cyclone, and the radius of maximum winds (based on QuikSCAT) was very close to the center, also more typical of tropical cyclones... on balance, it was more tropical than subtropical.[9]

Clark Evans of Florida State University reported that forecasting tools showed that the system's structure was consistent with that of a subtropical or marginally tropical cyclone.[1] NASA, a non-meteorological government agency, asserted that the system was a subtropical cyclone.[3]

In its review of the 2006 Atlantic hurricane season, the Canadian Hurricane Centre considered this to be an extratropical cyclone.[5]

Since this system had one-minute sustained winds of 100 km/h (65 mi/h), which are above the 60 km/h (39 mi/h) boundary between a depression and a storm, it would qualify as a named storm if it was a tropical or subtropical cyclone. However, neither of the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Centers for the eastern north Pacific, the National Hurricane Center[10] and the Central Pacific Hurricane Center,[11] include this system in their annual archives, nor is it included in the official "best track" file.[8] Hence, this system is not an official tropical or subtropical cyclone of the 2006 Pacific hurricane season.

See also

- 2006 Pacific hurricane season

- 2018 Pacific hurricane season

- 1951 Hawaii cyclone

- 1975 Pacific Northwest hurricane

- 1996 Lake Huron cyclone

- Hurricane Catarina

- Tropical Storm Omeka

- Subtropical Cyclone Katie

- Subtropical Cyclone Lexi

- Tropical Storm Rolf

- Cyclone Qendresa

- Cyclone Numa

- Subtropical Storm 96C

- South Atlantic tropical cyclone

- Mediterranean tropical cyclone

References

- Gary Padgett. "Possible Tropical Cyclone". Archived from the original on 2008-08-02. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- Dr. Jeff Masters (November 2, 2006). "Thingamabobbercane forms off coast of Oregon". Weather Underground. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "Subtropical Storm off the Coast of Oregon". NASA. November 2, 2006. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "First Storm Set to Wow Oregon Coast". Beach Connection. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- "2006 Atlantic Hurricane Season Review". Canadian Hurricane Center. 2007-05-22. Archived from the original on 2007-07-26. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- Gary Padgett; Karl Hoarau. "Global Tropical Cyclone Tracks — November 2006". Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- "Tropical Storm (TS) 16W (Wene*)". 2000 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report. Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2019". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- "Thingamabobbercane revisited". Jeff Masters' Blog. Weather Underground. November 8, 2006. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "2006 Eastern Pacific Hurricane Season". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- Andy Nash; Tim Craig; Sam Houston; Roy Matsuda; Jeff Powell; Ray Tanabe; Jim Weyman (July 2007). "2006 Tropical Cyclones Central North Pacific". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 3 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

External links

| Wikinews has related news: |