Skardu

Skardu (Urdu: سکردو, IPA: [skərduː]; Balti: སྐར་དོ་་) is a city in Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan, and serves as the capital of Skardu District. Skardu is located in the 10 kilometres (6 miles) wide by 40 kilometres (25 miles) long Skardu Valley, at the confluence of the Indus and Shigar Rivers[1] at an elevation of nearly 2,500 metres (8,202 feet). The city is an important gateway to the eight-thousanders of the nearby Karakoram Mountain range. The town is located on the Indus river, which separates the Karakoram Range from the Himalayas.[2]

Skardu

| |

|---|---|

Top left to right: Deosai National Park, Shangrila Resort, Satpara Lake, Manthokha Waterfall and Trango Towers | |

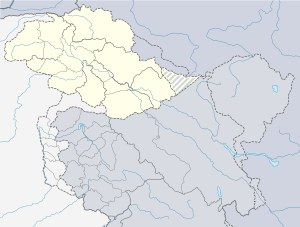

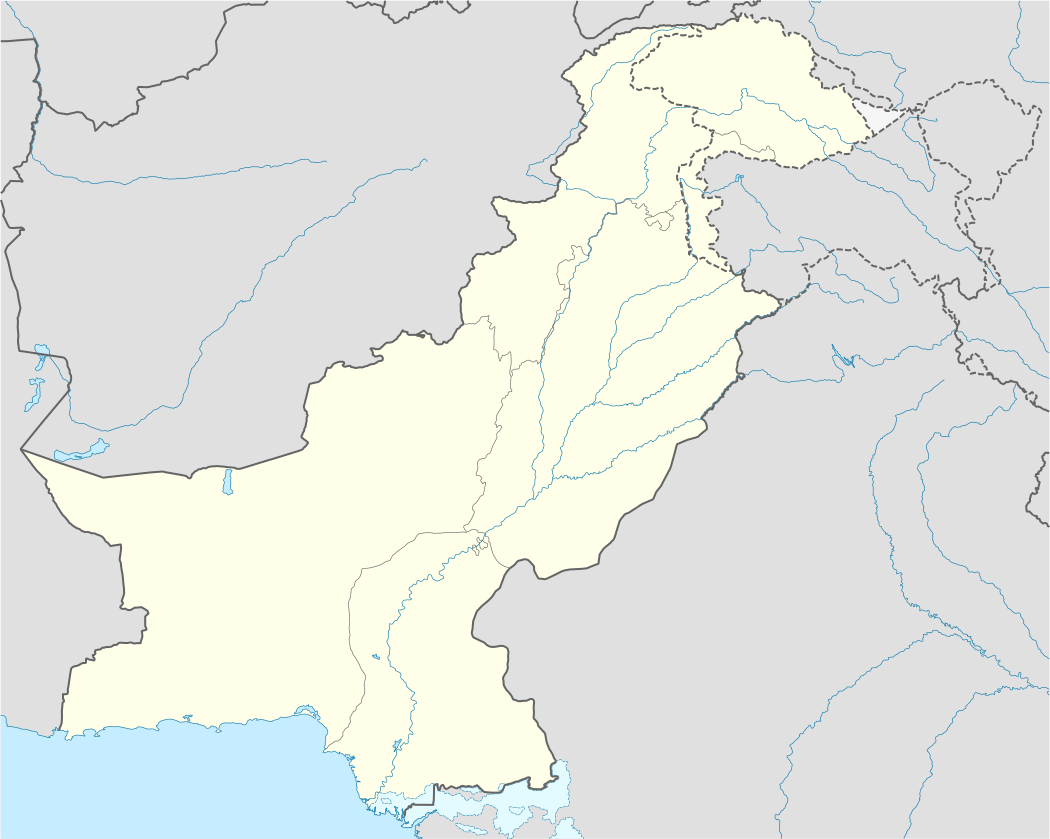

Skardu Location in the Karakoram region  Skardu Skardu (Pakistan) | |

| Coordinates: 35°17′25″N 75°38′40″E | |

| Country | Pakistan |

| Autonomous territory | Gilgit Baltistan |

| District | Skardu |

| Elevation | 2,228 m (7,310 ft) |

| Time zone | PKT |

| • Summer (DST) | GMT+5:00 |

Etymology

The name "Skardu" is believed to be derived from the Balti word meaning "a low land between two high places."[3] The two referenced “high places" are Shigar city, and the high-altitude Satpara Lake[3]

The first mention of Skardu dates to the first half of the 16th century. Mirza Haidar (1499–1551) described Askardu in the 16th-century text Tarikh-i-Rashidi Baltistan as one of the districts of the area. The first mention of Skardu in European literature was made by Frenchman François Bernier (1625–1688), who mentions the city by the name of Eskerdou. After his mention, Skardu was quickly drawn into Asian maps produced in Europe, and was first mentioned as Eskerdow the map "Indiae orientalis nec non insularum adiacentium nova descriptio" by Dutch engraver Nicolaes Visscher II, published between 1680–1700.

History

Early history

The Skardu region was part of the cultural sphere of Buddhist Tibet since the founding of the Tibetan Empire under Songsten Gampo in the mid 7th-century CE.[3] Tibetan tantric scriptures were found all over Baltistan until about the 9th century.[3] Given the region's close proximity to Central Asia, Skardu remained in contact with tribes near Kashgar, in what is now China's westernmost province of Xinjiang.[5]

Following the dissolution of Tibetan suzerainty over Baltistan around the 9th-10th century CE, Baltistan came under control of the local Maqpon Dynasty, a dynasty of Turkic extraction,[3] which according to local tradition, is said to have been founded after a migrant from Kashmir named Ibrahim Shah married a local princess.[3]

Maqpon period

.jpg)

Around the year 1500, Maqpon Bokha was crowned ruler, and founded the city of Skardu as his capital.[3] The Skardu Fort was established around this time.[3] During his reign, King Makpon Bokha imported craftsmen to Skardu from Kashmir and Chilas to help develop the area's economy.[3] While nearby Gilgit fell out of the orbit of Tibetan influence, Skardu's Baltistan region remained connected due to its close proximity to Ladakh,[6] the region which Skardu and neighbouring Khaplu routinely fought against.[5] Sikhs traditionally believe that Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, visited Skardu during his second udasi journey between 1510 and 1515.[7]

Mughal period

In the early 1500s, Sultan Said Khan of the Timurid Yarkent Khanate, based in what is now Xinjiang province of China, raided Skardu and Baltistan.[8] Given the threat illustrated by the Sultan Said's invasion, Mughal attention was roused, prompting the 1586 conquest of Baltistan by the Mughal Emperor Akbar.[5] The local Maqpon rulers pledged allegiance, and from that point onwards beginning with Ali Sher Khan Anchan, the kings of Skardu were mentioned as rulers of Little Tibet in the historiography of the Mughal Empire.[9]

Mughal forces again incurred into the region during the reign of Shah Jahan in 1634-6 under the forces of Zafar Khan, in order to settle a dispute to Skardu's throne between Adam Khan, and his elder brother Abdul Khan.[10][11] It was only after this point, during the rule of Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, that Skardu's ruling family was firmly under Mughal control.[12] The ability of the Mughal crown to fund expeditions to territories of marginal value, such as Baltistan, emphasizes the wealth of the Mughal coffers.[13]

Dogra rule

In 1839, Dogra commander Zorawar Singh Kahluria defeated Balti forces in battles at Wanko Pass and Thano Kun plains, clearing his path for invasion of the Skardu valley.[14] He seized Skardu Fort on behalf of the Dogra Kingdom based in Jammu.[1] Singh's forces massacred a large number of the garrison's defenders, and publicly tortured Kahlon Rahim Khan of Chigtan in front of a crowd of local Baltis and their chiefs.[15]

Dogra forces failed in their 1841 attempt to conquer Tibet. Following their defeat, Ladakhis rose in rebellion against Dogra rule.[16] Baltis under the leadership of Raja Ahmed Shah soon also rose in rebellion against the Dogras, and so Maharaja Gulab Singh dispatched his commander Wazir Lakhpat to recapture Skardu. His forces were able to convince a guard to betray the garrison by leaving a gate unlocked, thereby allowing Dogra forces to recapture the fort and massacre its Balti defenders.[16] The Raja of the Baltis was forced to pay an annual tribute to the Dogra Maharaja in Jammu, while the fort's provisions were provided for by the Balti Raja.[16]

Following the Dogra victory, Muhammad Shah was crowned Raja of Skardu in return for his loyalty to the Jammu crown during the rebellion, and was able to exercise some power under Dogra administration.[16] Military commanders held real governing power in the area until 1851 when Kedaru Thanedar was installed as a civilian administrator of Baltistan.[16] During this time, Skardu and Kargil were governed as a single district.[16] Ladakh would later be joined to the district, while Skardu would serve as the district's winter capital, with Leh as the summer capital, up until 1947.[16]

Under the administration of Mehta Mangal between 1875 and 1885, Skardu's Ranbirgarh was built as his headquarters and residence.[16] A cantonment, and various other government buildings were built in Skardu during this period.[16] Sikhs from Punjab were also encouraged to migrate to Skardu in order to set up commercial enterprises during this period.[16] The Sikh population prospered, and continued to grow - eventually also settling in nearby Shigar and Khaplu.[16]

1947–48 Kashmir War

After the Partition of British India, on 22 October 1947, Pakistan launched a tribal invasion of Kashmir by Pashtuns leading to the Maharaja Hari Singh acceding to India.[17] The Gilgit Scouts, under the leadership of Major William Brown, mutinied on 1 November 1947, bringing the Gilgit Agency under the control of Pakistan.[18][19] Major Aslam Khan took over the command of the Gilgit Scouts, organised a force of some 600 men from the rebels and local recruits, and launched attacks on the remaining parts of the State under Indian control.[20] Skardu was an important target because Aslam Khan felt that Gilgit could be threatened from there.[21] The Skardu garrison defended by a contingent of 6th Jammu and Kashmir Infantry under the command of Col. Sher Jung Thapa.[22] The initial attack was repulsed, but the city fell into the rebel hands.[22] After holding the garrison for 6 months and 3 days, Thapa and his forces surrendered on 14 August 1948, Pakistan's independence day.[22][23][24]

Geography

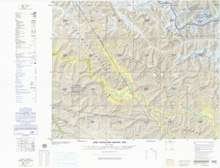

Topography

Skardu's Airport is situated at an elevation of 2,230 metres (7,320 feet) above sea level, though the mountain peaks surrounding Skardu reach elevations of 4,500–5,800 metres (14,800–19,000 feet).[25] Upstream from Skardu are some of the largest glaciers in the world, including the Baltoro Glacier, Biafo Glacier, and Chogo Lungma Glacier.[25] Some of the surrounding glaciers are surrounded by some of the world's tallest mountains, including K2, the world's second tallest mountain at 8,611 metres (28,251 feet), Gasherbrum at 8,068 metres (26,470 feet), and Masherbrum at 7,821 metres (25,659 feet).[25] The Deosai National Park, the world's second highest alpine plain, is located upstream of Skardu as well. Downstream from Skardu is located the Nanga Parbat mountain at 8,126 metres (26,660 feet).[25]

The Skardu Valley, at the confluence of the Indus and Shigar Rivers, is 10 kilometres (6 miles) wide by 40 kilometres (25 miles) long. Active erosion in the nearby Karakoram Mountains has resulted in enormous deposits of sediment throughout the Skardu valley.[25] Glaciers from the Indus and Shigar valleys broadened the Skardu valley between 3.2 million years ago up to the Holocene approximately 11,700 years ago.[25]

Climate

Skardu features a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk). The climate of Skardu during the summer is moderated by its mountain setting; the intense heat of lowland Pakistan does not reach it. The mountains block out the summer monsoon, and summer rainfall is thus quite low. However, these mountains result in very severe winter weather. During the April-to-October tourist season, temperatures vary between a maximum of 27 °C (81 °F) and a minimum (in October) 8 °C (46 °F).

Temperatures can drop to below −10 °C (14 °F) in the December-to-January midwinter period. The lowest recorded temperature was −24.1 °C (−11 °F) on 7 January 1995.[26]

| Climate data for Skardu | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

24.0 (75.2) |

29.6 (85.3) |

34.4 (93.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

41.0 (105.8) |

41.0 (105.8) |

38.2 (100.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

41.0 (105.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

6.1 (43.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.2 (88.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −8.0 (17.6) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

1.5 (34.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.7 (49.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −24.1 (−11.4) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

0.4 (32.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

7.0 (44.6) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−17.2 (1.0) |

−24.1 (−11.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 27.5 (1.08) |

25.9 (1.02) |

36.9 (1.45) |

31.3 (1.23) |

25.3 (1.00) |

9.0 (0.35) |

9.8 (0.39) |

12.2 (0.48) |

9.3 (0.37) |

7.3 (0.29) |

5.6 (0.22) |

16.3 (0.64) |

172.7 (6.80) |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:00 PST) | 64.3 | 52.0 | 34.9 | 25.6 | 24.6 | 22.3 | 27.3 | 30.7 | 29.9 | 31.2 | 36.6 | 56.2 | 29.6 |

| Source: Pakistan Meteorological Department[26] | |||||||||||||

Geology

Skardu is located along the Kohistan-Ladakh terrane, formed as a magmatic arch over a Tethyan subduction zone that was later accreted onto the Eurasian Plate.[25] The region has low seismic activity compared to surrounding regions, suggesting that Skardu is located in a passive structural element of the Himalayan thrust.[25] The stone in the Skardu region is Katzara schist, with a Radiometric age of 37 to 105 million years.[25]

Numerous complex granitic pegmatites and a few alpine-cleft metamorphic deposits are found in the Shigar Valley and its tributaries. Shigar Valley contains the Main Karokoram Thrust separating the metasediments (chlorite to amphibolite grade) on the Asian plate from the southern volcanoclastic rocks of the Kohistan-Ladakh island arc.

Tourism

Skardu, along with Gilgit, is a major tourism, trekking and expedition hub in Gilgit–Baltistan. The mountainous terrain of the region, which includes four of the world's 14 Eight-thousander peaks, attracts tourists, trekkers and mountaineers from around the world. The main tourist season is from April to October; except at this time, the area can be cut off for extended periods by the snowy, freezing winter weather.

Mountains

_skardu._photo_by_me.jpg)

Accessible from Skardu by road, the nearby Askole and Hushe are the main gateways to the snow-covered 8,000-metre (26,000-foot) peaks including K2, the Gasherbrums, Broad Peak, and the Trango Towers, and to the huge glaciers of Baltoro, Biafo and Trango. This makes Skardu the main tourist and mountaineering base in the area, which has led to the development of a reasonably extensive tourist infrastructure including shops and hotels. The popularity of the region results in high prices, especially during the main trekking season.

Deosai National Park

Treks to the Deosai Plains, the second highest in the world at 4,114 metres (13,497 ft) above sea level, after the Chang Tang in Tibet, either start from or end at Skardu. In the local Balti language, Deosai is called Byarsa བྱིར་ས, meaning 'summer place'. With an area of approximately 3,000 square kilometres (1,158 sq mi), the plains extend all the way to Ladakh and provides a habitat for snow leopards, ibex, Tibetan blue bears and wild horses.

Skardu Fort

Skardu Fort or Kharphocho Fort lies on the eastern face of the Khardrong or Mindoq-Khar ("Castle of Queen Mindoq") hill 15 metres (49 feet) above Skardu town. The fort dates from the 8th century CE and contains an old mosque probably dating back to the arrival of Islam in the 16th century CE. The fort provides a panoramic view of Skardu town, the Skardu valley and the Indus River. It was built by Maqpon dynasty rulers of Baltistan. It was a seven-storey building. Mostly local people say that Kharpoocho is made by a ghost as they were servants of the ruler of that time.

Kharphocho (Skardu) fort was built on a design similar to that of Leh Palace and the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet. The name Kharpochhe means the great fort — Khar in Tibetan means castle or fort and Chhe means great.

Shigar Fort

Located on the route to the world's second highest mountain, K-2 is Shigar Fort. It is also known as Fong-Khar, which in the local language means the "Palace on the Rock". The complex at Shigar comprises the 400-year-old fort/palace and two more recent buildings: the "Old House" and the "Garden House". The former palace of the Raja of Shigar has been transformed into a 20-room heritage guesthouse, with the grand audience hall serving as a museum of Balti culture and featuring select examples of fine wood-carvings, as well as other heritage objects.

Kachura Lakes

There are two Kachura lakes — the less well-known (Upper) Kachura Lake and the more famous Shangrila Lake ("Lower Kachura Lake"). Shangrila Lake is home to the Shangrila Resort hotel complex (possibly the reason for the lake's alternative name), built in a Chinese style and another popular destination for tourists in Pakistan-administered Kashmir. The resort has a unique restaurant, set up inside the fuselage of an aircraft that crashed nearby. Kachura Lake is famous for its deep blue waters.

Satpara Lake

Satpara Lake is Skardu Valley's main lake. In 2002, the Federal Government decided to build a dam on the Satpara Lake allocating $10 million to the project, in 2004. Progress has, however, been slow. Satpara Lake is 6 miles (9.7 km) from Skardu. Satpara Lake is one of the largest fresh water lakes in the countryside offering trout fishing and row boating. This lake is the source of Skardu's drinking water. The dam was mostly completed in 2011 and four powerhouse units are operational; the latest started operation in June 2013.

Transport

Road

The normal road route into Skardu is via the Karakorum Highway and a Skardu Road (S1) into the Skardu Valley from it. Roads once linked Skardu to Srinagar and Leh, though none are open for cross-LoC travel.

Skardu's weather can have adverse effects on transport in and out of the region, as Skardu is often snowbound during the winter months. Roads in and out of Skardu can be blocked for extended periods of time, sometimes leaving air travel as the only feasible alternative.

Air

Skardu Airport is served by a daily direct flight from Islamabad. Air travel in winter is subject to disruption due to the unpredictable winter weather.

Infrastructure

Satpara Dam

The Satpara Dam development project on the Satpara Lake was inaugurated in 2003. It was expected to be completed in December 2006; now the development work will be completed in December 2013. It is 6 km (4 mi) south of Skardu city and is at an elevation of 2,700 metres (8,900 ft) from mean sea level. The main source of water is melting ice of the Deosai plains during the summer season. Now Satpara Dam provides drinking water to the whole city of Skardu and agricultural water to major areas of Skardu, for example, Gayoul, Newrangha, Khlangranga, Shigari Khurd, etc.[27]

It is a multipurpose project, which will produce 17.36 megawatts hydro generation, irrigate 15,000 acres (61 km2) of land and provide 13 cusecs drinking water daily to Skardu city.[27]

See also

- Baltistan

- Ladakh

- Northern Areas

- Satpara Dam

- Haji Gham

References

- Pirumshoev & Dani, The Pamirs, Badakhshan and the Trans-Pamir States 2003, p. 245.

- Skardu, District. "Skardu District". www.skardu.pk. Skardu.pk. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Dani, The Western Himalayan States 1998, p. 220

- Ahmed, M. (2015), "Interdependence of Biodiversity, Applied Ethnobotony and Conservation", in Münir Öztürk; Khalid Rehman Hakeem; I. Faridah-Hanum; Recep Efe (eds.), Climate Change Impacts on High-Altitude Ecosystems, Springer, p. 456, ISBN 978-3-319-12859-7

- Dani, The Western Himalayan States 1998, p. 219

- Dani, The Western Himalayan States 1998, p. 221.

- Gandhi, Surjit Singh (2007). History of Sikh Gurus Retold: 1469-1606 C.E. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 9788126908578.

- Adshead, S. A. M. (27 July 2016). Central Asia in World History. Springer. ISBN 9781349226245.

- "Vacations, Holiday, Travel, Climbing, Trekking". Skardu.pk. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Pirumshoev & Dani, The Pamirs, Badakhshan and the Trans-Pamir States 2003, p. 244.

- Afridi, Banat Gul (1988). Baltistan in History. Emjay Books International.

- International Association for Tibetan Studies (1 January 2006). Tibetan Borderlands: PIATS 2003: Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Oxford, 2003. Brill. ISBN 9789004154827.

- Dale, Stephen F. (24 December 2009). The Muslim Empires of the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316184394.

- Kaul, Shridhar; Kaul, H. N. (1992). Ladakh Through the Ages, Towards a New Identity. Indus Publishing. ISBN 9788185182759.

- Charak, Sukhdev Singh (8 September 2016). GENERAL ZORAWAR SINGH. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting. ISBN 9788123026480.

- Kaul, H. N. (1998). Rediscovery of Ladakh. Indus Publishing. ISBN 9788173870866.

- Nawaz, Shuja (May 2008), "The First Kashmir War Revisited", India Review, 7 (2): 115–154, doi:10.1080/14736480802055455

- Brown, Gilgit Rebellion 2014, p. 264.

- Schofield 2003, pp. 63-64.

- Dani, History of Northern Areas of Pakistan 2001, p. 362–.

- Brown, Gilgit Rebellion 2014, p. 268.

- Francis, J. (30 August 2013). Short Stories from the History of the Indian Army Since August 1947. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9789382652175.

- Harbans Singh, Spare a thought for those defenders of Skardu, The Tribune, 19 August 2015.

- Cheema, Brig Amar (2015), The Crimson Chinar: The Kashmir Conflict: A Politico Military Perspective, Lancer Publishers, pp. 51–, ISBN 978-81-7062-301-4

- Schroder Jr, John F. (2002). Himalaya to the Sea: Geology, Geomorphology and the Quaternary. Routledge. ISBN 9781134919772.

- "Skardu Climate Data". web.archive.org. 2014. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- "SATPARA DAM PROJECT Updated as". Wapda.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Bibliography

- M. S. Asimov; C. E. Bosworth, eds. (1998), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV, Part 1 — The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century — The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO, ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1998), "The Western Himalayan States", Ibid, UNESCO, pp. 215–225, ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1

- Chahryar Adle; Irfan Habib, eds. (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. V — Development in contrast: From the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pirumshoev, H. S.; Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2003), "The Pamirs, Badakhshan and the Trans-Pamir States", Ibid, pp. 225–246

- Brown, William (2014), Gilgit Rebelion: The Major Who Mutinied Over Partition of India, Pen and Sword, ISBN 978-1-4738-4112-3

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2001), History of Northern Areas of Pakistan: Upto 2000 A.D., Sang-e-Meel Publications, ISBN 978-969-35-1231-1

- Petr, T. (1999). Fish and Fisheries at Higher Altitudes: Asia. Food & Agriculture Org. ISBN 978-92-5-104309-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Jettmar, Karl et al. (1985): Zwischen Gandhara und den Seidenstrassen: Felsbilder am Karakorum Highway: Entdeckungen deutsch-pakistanischer Expeditionen 1979–1984. 1985. Mainz am Rhein, Philipp von Zabern.

- Jettmar. Karl (1980): Bolor & Dardistan. Karl Jettmar. Islamabad, National Institute of Folk Heritage.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Skardu. |

- Skardu - Emerging Pakistan