Ship and boat building in Whitby

Ship and boat building in Whitby[note 2] was a staple part of the industry of Whitby, North Yorkshire, England between the 17th and 19th centuries. Building continued throughout the 20th century but on a smaller scale both in terms of output and overall size of the vessels being built.

The position of the town, being geographically hard to reach due to the surrounding moorland, meant that until the coming of the railways, the town was largely reliant on the sea for imports and trade. Whitby was a safe haven from storms in the North Sea and was also a useful stop-off point for the resupply of ships. Given Whitby's status as a whaling port, and supply port, it developed a burgeoning ship and boat-building business that ranged from ocean-going barques, to small fishing cobles. One builder still exists in the town, Parkol Marine, which up to 2019, had constructed over 40 trawlers and other ships, mainly for the fishing industry along the Yorkshire Coast, and other businesses in the north-east of Scotland.

During the height of the ship and boat building industry in Whitby (the 1790s), the town was ranked as the third largest boat building centre after London and Newcastle. The town had at least 20 shipbuilders spread across different yards, though not all were in operation at the same time as each other. As some businesses went bankrupt, others assumed control of their yards, which led to some shipbuilders switching yards during the years of their operations.

Background

Throughout Whitby's early history, the town was a small collection of buildings clustered around the east cliff side of the present town, underneath the cliffs that held the church and abbey.[4] The east side of the town developed as the fishing village, whereas the growth of the western side, was accelerated through the 18th and 19th centuries by the ship and boat building industries.[5] Whitby has had a fishing fleet since at least the 14th century,[6] but the growth in larger shipping both entering and being built in the harbour, was driven by the local alum industry that had several processing sites along the coast of Yorkshire.[7][8] Alum was originally imported from Italy and was a monopoly industry for the Papacy, with one story suggesting that the supply was cut off during the Reformation. Another tale involved a way to get alum cheaper locally than by importing it at a vastly increased price from Italy. This story relates that Sir Thomas Chaloner visited the alum works owned by the Pope and recognised that the same rocks existed beneath his estate in Guisborough, North Yorkshire. He spirited away several of the Italian workers and set about his own alum business, which could produce alum at £40 cheaper (£12 instead of £52) than the imported Italian product. This led to Pope Clement III (term 1187-1191) excommunicating Chaloner and any others in the trade.[9]

The alum industry in Whitby was started c. 1608,[10] and the river and harbour provided a good starting point for the outward transportation of alum and an appropriate receiving point for inward goods needed in the alum producing process, such as coal and human urine.[11][12][13][note 3] Long before the alum trade, Whitby was noted as being a safe haven for shipping to wait out storms in the North Sea, and as a convenient stopping off point between the Humber and the Tees rivers.[15]

18th century

The mass building of maritime vessels is recorded as having started around 1730,[16] though this does not acknowledge the small-scale building of fishing cobles, which had been happening along the Yorkshire Coast for centuries beforehand. George Young attributes this to what was built before as being simply boats, whereas, after the early 18th century, the harbour was greatly enlarged which allowed ships to be built.[17] The town had a fishing industry during this time, but it was a very small operation in comparison to the fishing fleets at Robin Hood's Bay and other ports on the Yorkshire Coast. However, until the expansion of the upper harbour at Whitby in the 1730s, fishing boats were built on the seaward side of the bridge straddling the upper and lower harbours.[18] Also, vessels registered to the ports of London and Newcastle in 1626 are described as having been built in Whitby, with one ship, The Pelican, weighing 170 tonnes (190 tons), being constructed by Henry Potter and Christopher Bagwith.[19]

But traces of shipbuilding can be found even further back; in 1301, the town was called upon to furnish a vessel for use against the Scots. Again in 1544, the town stated it would "provide ships for war", on condition that the harbour was repaired,[20] and, in 1724, Daniel Defoe visited the town and claimed Whitby as a place "....where they build very good ships for the Coal Trade[sic], and many of them too, which makes the Town[sic] rich."[21]

Shipbuilding on an industrial scale seems to have commenced around 1717, when Jarvis Coates launched William and Jane, a three-masted vessel weighing 237 tonnes (261 tons).[22] Coates had been in business since 1697, when his name first appears in a rate book.[23] By 1706, the town was the sixth largest port in Britain, having over 130 vessels built in Whitby.[24] A dry dock was uncovered underneath a car park on Church Street in the town during building works in 1998. The town had a plethora of dry docks for the maintenance of ships during the 18th and 19th centuries. The dry docks at Whitby were the first in the region, and only the second behind those in Portsmouth which were built between 1680 and 1700.[24]

The most famous of the shipyards was that of Thomas Fishburn, who along with Thomas Brodrick, built many vessels, including the famous 'Whitby Cats'.[25] The Cat was a particular type of vessel that was described as being "bluff in the bow and flat in the floors for maximum capacity".[26][27] The ships were colliers, and transported coal from Newcastle to London and points between in the days before the railways.[28] The Cat's shallow draught allowed them to beach and unload their cargo whilst stranded and be refloated come high tide.[29][30]

The term 'Cat' could be seen as confusing, as at least two writers, Peter Moore and Karl Heinz, have identified differences between a 'Bark' and a 'Cat'.[31] Three of Fishburn's vessels (Earl of Pembroke, Marquis of Granby and Marquis of Rockingham) were all purchased and renamed Endeavour, Resolution and Adventure. Resolution and Adventure were chosen by Cook himself when they were tied up in Whitby. All three had originated in Fishburn's yard, an impact that Moore states as being

...far from being an obscure business on a provincial river, Fishburn's shipyard was becoming something of a Georgian Cape Canaveral: a launch site for expeditions to new worlds.[32]

Cook was known to be familiar with these ships, having served on board several cats and barks as part of his apprenticeship during his early days in Whitby.[33]

The shipbuilding industry led to many other industries in the town such as rope-making and sail making. Two roperies were on the eastern bank, and three others on the western bank of the river. One ropery, at Spital Bridge on the eastern side of the river, where the Spital Beck flows into the Esk, was over 380 yards (350 m) long.[34] This was used up until just after the First World War.[35] At least four sailmakers were located in the town (usually in buildings known as sail lofts.)[36] Whilst most of these were located on the side of the shipyards or the water, one, owned by Campion was situated in the upper part of Bagdale and produced a special type of sailcloth which did not use starch in its preparation as most other manufacturers did.[37] The yardage of cloth produced in the late 1770s was about 5,000 yards (4,600 m) annually, of which, most was supplied to the Royal Navy in London.[38]

Timber yards were also one of the main functions of the town before the use of iron and steel in shipbuilding. Timber, hemp, flax and tar were all needed for the shipbuilding industry, and many of these came from the Baltic States via ships.[39] But as the Gulf of Riga traditionally froze over winter, many Whitby ships were in for repair, which led to an increase in the number of dry docks in the harbour area.[40] The winter work that was carried out on the vessels was a lucrative sideline to the shipbuilders, as in the latter part of the 17th century, this brought in around £2,200 to the port every year. This sum can be compared with the wages earned over one year for a captain of a ship (£131) and an able seaman (£43).[41]

Timber was originally sourced from Yorkshire, probably from the Vale of Pickering area, and it required a good number of oak trees per each ship built. Marquis of Granby (later the famous HMS Endeavour), was estimated to have been constructed from at least 200 mature oaks.[42] As Whitby was isolated from the rest of Yorkshire by its surrounding moorland, transportation of the oaks was problematic as it took an old route over Lockton High Moor.[43] It is believed that the 1759 act to provide a turnpike between Pickering and Whitby, was in part down to the necessity of transporting wood from the Pickering area to the Whitby Shipyards. The route still exists today as the A169 road.[44] Timber was later also imported from Hull and other English ports.[45]

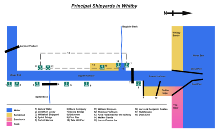

This diagram is not to scale and is representational only.

During the 1790s, the ship and boat building industry in Whitby was at its zenith, with almost 12,000 tonnes (13,000 tons) of shipping launched in the year from 1790 to 1791. This made Whitby the third largest producer of shipping in Britain after London and Newcastle, with Hull, Liverpool, Yarmouth, Whitehaven and Bristol, being less productive than Whitby.[47][48]

19th century

A peace treaty signed between the warring parties at the cessation of the Napoleonic Wars, created a decline in the shipbuilding industry in Whitby, however, by the 1830s, shipbuilding was on the increase again.[49]

In 1870, the yard of Turnbull and Son switched to constructing ships made of iron instead of wood. A year later in 1871, Turnbull's launched the first Whitby-built steamship, SS Whitehall.[50] The number of ships and overall tonnage grew steadily and provided a keen income to the yard. In 1882, they launched eight ships with a combined weight of over 13,000 tonnes (14,000 tons).[51] However, in the following year there was a depression in the market and Turnbull's only launched four ships with a combined weight of 7,000 tonnes (7,700 tons).[52] This saw their workforce decimated from nearly 800 men to just 70.[53] Turnbull and Son launched their last vessel, SS Broomfield in 1902, which brought and end to the great shipbuilding in Whitby as Turnbull and son were the last "significant shipbuilders".[54] The last years of building ships into the early twentieth century, saw their displacement rated at over 5,700 tonnes (6,300 tons), which was proving too much for the width available at the swing bridge in Whitby.[55] Even though the swing bridge was replaced in 1909,[56] with a width of 70 feet (21 m),[57][note 4] it was too late for the shipbuilding industry as the skilled workers made redundant from Turnbull and Son, went off to work in other shipyards away from the River Esk and Whitby.[61] Another cause for the loss of the shipbuilding business was that by the turn of the 20th century, steel and iron were the materials that ships were mostly made from, and Whitby could not compete with shipyards on the Tyne, Tees and Humber rivers who had a plentiful supply of metals on their doorstep.[62]

20th century

Other than an occasional or small boat build, ship and boat building disappeared from Whitby, though the widened 1909 swing bridge ironically allowed captured enemy ships from the First World War to be brought into the upper harbour and scrapped.[63] Boats of that size, typically 5,000 tonnes (5,500 tons), would not have been able to reach the upper harbour through the old bridge.[64] Also during the First World War, the former Turnbull shipyard was sold to the Albion Trust who were hoping for a resurgence in shipbuilding at Whitby to support the war effort. In 1917, two ferro-concrete vessels were launched from Whitby, but no further building was undertaken.[65]

Boat building on a regular basis returned to Whitby in the late 1990s, when Parkol Marine Engineering, an established repair and engineering business, started constructing small fishing vessels such as trawlers and seine craft.

Many of the shipyards on the western bank of the River Esk have been lost, first under the railway, and during the latter half of the twentieth century, to a supermarket and marina development.[66]

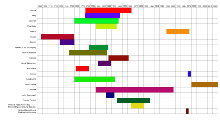

Builders

The table below gives descriptions of the various ship and boat builders known to have existed in Whitby, though the list is not exhaustive. The image shows the relative timelines of each company, though it should be remembered that shipbuilding largely ended in 1902, but that Smales still existed as a company until the 1940s as a repair yard. Similarly, Parkol Marine started up in 1980, but did not start building boats until the late 1990s. Some yards possibly also diversified into ship-breaking, with one breakers known as Clarkson's operating between 1919 and 1921, though it is unknown if this is the same family who went on to make cobles between the 1930s and the 1970s.[67]

Some of the concerns listed amalgamated or took on partners for certain jobs; these are listed if it is specific enough to warrant that information.

| Name | Dates of operation | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barrick | c. 1781–1866 | Location shared with the Barry shipyard at the mouth of Bagdale Beck, (known as Dock End).[68] | Noted shipbuilders, examples being the Isabella (1827 ship), Lotus (1826 ship) and the Regret (1814 ship).[69] |

| Barry (Family) | c. 1780–1845 | West side of the River Esk | Barry's was a venture started by Robert Barry and managed by three generations of the Barry family. The yard was sold in 1845 to the York and North Midland Railway company (later part of the North Eastern Railway), who built the new Whitby Town railway station on the site.[70][71] |

| Campion (also Campion, Irving & Bilbie)[72] | c. 1760–1842 | Just upstream from Spital Bridge (east side of the River Esk)[73] | Originally opened by William Coulson, the yard came into the possession of the Campion family, who, in 1842, went bankrupt. The yard was later acquired by Turnbull and Son in 1850.[74] |

| Peter Cato | c. 1802–1829 | Occupied premises at Green Lane and Whitehall Shipyard[75] | Cato worked independently, but also as part of Eskdale, Smales & Cato (1803) and Eskdale Cato & Co (1803–1808).[76] |

| Clarkson | c. 1933–c. 1976[77][78] | Clarkson's boat building yard was described as being 200 yards (180 m) south of Dock End.[79] | Clarkson's was noted for building cobles,[80] and was probably one of the shipyards to do this in Whitby on a regular basis. Dates of the business are not exact, but William Clarkson is recorded as building boats in 1933, with Gordon Clarkson building boats up to at least 1976. A ship-breakers known a s Clarkson existed at Whitby between 1919 and 1921. |

| Coates | c. 1697–1759 | Walker Sands, by Bagdale Beck mouth (Dock End). This is where the current quayside is on the left bank of the River Esk; in Coates' time, it was a sandbank at low tide.[81] | The shipyard was the first to be recorded in Whitby and was located at Dock End, where Bagdale Beck flowed into the harbour. Coates' shipyard was said to have dominated the shipbuilding industry in Whitby for 40 years.[82] This site has been moved further east and infilled and is the point of a roundabout and road junction.[83] Part of the current Whitby Town railway station used to almost abut the site. At some point. Bagdale Beck was culverted, and whilst it still runs into the harbour, the point where it empties is not discernible. The yard was lost to the Coates family in 1759 through bankruptcy and was taken over by the Barry family.[84] |

| Coulson | c. 1733–1750 | The first name listed as being the occupier at Whitehall shipyard between Spital Bridge and Larpool on the eastern bank of the Esk.[85] | Coulson came to Whitby from Scarborough sometime between 1733 and 1735. He died in 1750 and there is no record of anyone named Coulson carrying on the family business, although the yard survived in different ownership.[85][86] |

| Eskdale, Cato & Company (also Ingram Eskdale and Eskdale Smales & Cato) | 1787–c. 1823 | Whitehall Shipyard | Ingram Eskdale built ships between 1787 and 1807. He also built as Eskdale Smales & Cato in 1803 and as Eskdale, Cato & Company between 1803 and 1828, though it was 1823 before the name was no longer listed as a shipbuilder.[76][87][88] |

| Thomas Fishburn (later Fishburn & Brodrick) | c. 1750–1822[85] | Fishburn took a rental of the former Coates shipyard in 1750 afterall of the Coates family had died, bar Mercy Coates, who was Jarvis Coates' wife. When she died in 1759, Fishburn took full ownership of the yard.[89] Fishburn also constructed a dry dock at Boghall, which came into the possession of the Turnbull family in the late 19th century.[90] | Three ships from the Fishburn yard are probably the most famous of those constructed at Whitby. Fishburn's specialised in the Whitby Cat, a collier ship with a flat bottom. In 1768, the admiralty purchased the Earl of Pembroke and renamed her HMS Bark Endeavour, with a young seafarer James Cook taking her to Australia. Fishburn's also built HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure; both of which were used in the historic voyages by Cook and his entourage to the Southern Seas. The site of the shpyard was infilled as part of the works for the railway in the 1840s. One of the old grade II listed closed engine sheds, was built upon the former shipyard.[91][92] |

| Hobkirks | 1824-1862 | West side of the Esk | Hobkirks shipyard occupied land reclaimed from the Esk, which later became part of the railway dockside and later still, the marine development. Hobkirk's last shop was the Merrie England launched in 1862 and weighing 444 tonnes (489 tons).[93] |

| Holt and Richardson | c. 1804–1819 | Downstream from Spital Bridge on the east bank of the Esk[94] | Holt and Richardson were two of the original four members of the Dock Company who established a dry dock and shipyard on the eastern bank of the River Esk. In conjunction, the company produced 27 ships between 1804 and 1819.[95] Before these dates, they operated independently of each other and Holt was in a partnership with Reynolds during the 1790s.[76] Holt and Richardson operated the ropery at Spital Bridge during the early years of the 19th century.[34] |

| Hutchinson | c. 1763–c. 1787 | Hutchinson was one of several who had a yard at Dock End and the site is believed to be where the present Angel Inn is located on New Quay Road.[76] | Hutchinson sold his business to the Barry family c. 1787.[76][note 5] He is listed as being among those who built the Lotus in 1826, despite having relinquished his business some 50 years earlier. |

| Intrepid | c. 1974–c. 1979 | Whitehall Yard - previously run by Whitby Shipbuilding Company | Intrepid was a shipbuilding company based in Berwick-upon-Tweed who used a smaller site at Whitby.[97] |

| Langbourne[note 6] | c. 1760–1837[85] | On the eastern bank of the Esk further downstream than the mouth of the Spital Beck. Owned by the Dock Company, but leased out.[17] | The Langbourne's built a dry dock in their yard in 1760.[99] Langbourne's yard built the Diligence which was bought by the Admiralty in 1775 and renamed HMS Discovery. She sailed as part of Cook's last expedition to the Pacific.[100] |

| Parkol Marine | 1980–present | East side of the Esk, near Spital Bridge | Originally started out as an engineering yard for ship repairs. Ventured into boat building in the late 1990s. Has produced over 40 boats since then including trawlers, yachts and service boats.[101] The facility has the capability of accepting vessels uop to 148 feet (45 m) long and weighing 500 tonnes (550 tons) in its dry dock.[102] |

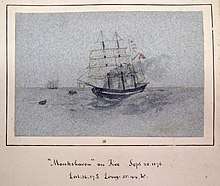

| Smales | c. 1800–1946 | On the eastern bank of the Esk further downstream than the mouth of the Spital Beck. Owned by the Dock Company, but leased out.[17] | The company was started by Gideon Smales, and continued by his son and grandson, followed by other members of the family. Their shipyard was noted as being the one that constructed the last wooden sailing ship in Whitby, The Monkshaven, in 1871.[note 7] The yard closed down in 1946.[105][106] |

| John Spencelayh | 1819–1835 | Larpool | Spencelayh built eleven ships between 1819 and 1835.[95] |

| Thomas Turnbull & Son | 1840–1902 | Whitehall Yard (see below), and a dry dock at Boghall, on the opposite (western) side of the River Esk near to Larpool Viaduct. They took over Whitehall yard in 1851.[59] | In 1840, the twenty-one year old Thomas Turnbull leased a yard at Larpool Wood that had had two previous owners. Turnbull was described as a capable draughtsman who had been apprenticed to the Barrick shipyard before forming his own company.[107] Originally, the Turnbull family built in wood, but switched to iron construction in 1870, which allowed for the closure of the Boghall site in 1899. Closure was precipitated by a downturn in business and a desire by shipowners to have ships that were larger than could exit the harbour at Whitby.[108][109] |

| Whitby & Robin Hood's Bay Shipbuilding and Graving Dock Company | c. 1866–c. 1891[110] | Located at the dry dock site on Church Street | Recorded as a company as far back as 1866. The company produced 91 tonnes (100 tons) of shipping in 1886,[111] with evidence showing the company to still be operating in 1891, though probably only in repairs at the graving (dry) dock.[112][113] |

| Whitby Shipbuilding Company | –1931[114] | Whitehall Yard | Taken over and closed by the National Shipbuilders Securities.[115] |

| Whitby Shipbuilding & Engineering Company | c. 1960–c. 1964 | Builder of small ships such as motor vessels weighing up to 50 tonnes (55 tons).[116] Was known to have been carrying out repairs in 1958.[117] | |

| Whitehall Yard | c. 1700–1902 | At Larpool on the eastern side[118] | Operated by various concerns during its lifetime (Ingram Eskdale,[119] Thomas Turnbull etc) the site was converted in the early part of the 21st century into a series of residential properties, some with access to the moorings.[120][121] |

In addition to the above, minor concerns that were in business for a short time (typically less than three years) were; Jonathan Lacey (1800–1803), Reynolds & Co. (1790) and William Simpson (1760).[76]

Ships

Whilst the list below is not exhaustive, it does cover some of the more notable ships to have been built in Whitby. Years in brackets are when the vessel was launched.

- Earl of Pembroke (1764), became HMS Endeavour in 1768 after being bought by the Admiralty

- Marquis of Granby (1770), became HMS Resolution in 1771 after being bought by the Admiralty

- Marquis of Rockingham (1770), which became HMS Adventure in 1771 after being bought by the Admiralty

- Dilligence (1774), became HMS Discovery in 1774 after being bought by the Admiralty

- Chapman (1777)

- Fishburn (1780)

- Ann and Amelia (1781)

- Sylph (1791)

- Hannah (1793)

- Ceres (1794)

- Coverdale (1795)

- Cambridge (1797)

- Herald (1799), became HMS Scourge in 1803 after being bought by the Admiralty

- Diadem (1800)

- Paragon (1800)

- Majestic (1801)

- Cullands Grove (1802)

- Majestic (1804)

- Kingston (1806)

- Mariner (1807)

- Aurora (1808)

- Ocean (1808)

- Hyperion (1810)

- Atlas (1811)

- Asia (1813)

- Regret (1814)

- Skelton (1818)

- Hercules (1822)

- Timandra (1822)

- Lotus (1826)

- Isabella (1827)

- Whitby (1837)

- Rosebud (1841)

Gallery

Former engine shed sited on a shipyard at Whitby

Former engine shed sited on a shipyard at Whitby Shipyard Sculpture Whitby with Abbey in background

Shipyard Sculpture Whitby with Abbey in background Former Whitehall Shipyard at Whitby

Former Whitehall Shipyard at Whitby Shipyard Sculpture Whitby

Shipyard Sculpture Whitby Parkol Marine shipyard Whitby

Parkol Marine shipyard Whitby Shipyard Sculpture plaque

Shipyard Sculpture plaque Spital Beck emptying into the River Esk at Spital Bridge

Spital Beck emptying into the River Esk at Spital Bridge Shipyard Sculpture with Parkol Marine in the background

Shipyard Sculpture with Parkol Marine in the background

See also

- Prospect of Whitby - a pub on the River Thames in London. Said to be so named after a ship regularly berthed there carrying coal from Newcastle, but the ship was built in, and named after, Whitby.[122] An area of Whitby to the south west of the town is known as Prospect Hill and was a viewpoint that offered travellers and sailors an extensive and commanding view of the harbour and the sea. The ship Prospect of Whitby was said to have been named after this area.[123]

Notes

- Dock End was historically known as Dark End when the whole area was very poorly lit at night. The name Dock End is probably a mispronunciation of Dark End. Another alternative name was Graving Dock, which indicates its repair yard status.[1]

- Ships and boats are often separated as to their definitions based on a number of criteria; mostly upon the belief that a ship can carry a boat, but a boat cannot carry a ship. Other definitions revolve around overall tonnage and whether or not the vessel was required to cross oceans or just stay close to the coast in particular areas, such as fishing boats before the days of ocean-going trawlers. Boats are still made in Whitby by Parkol Marine, but some ships have been built there too, most notable ones that were commanded by Captain Cook, such as HM Bark Endeavour.[2][3]

- Coal was traded through the port as far back as 1394, when the town was recorded as being a port for fish, coal and wool.[14]

- The width of the 1766 drawbridge was 32 feet (9.8 m) and its replacement swing bridge (1835) was 45 feet (14 m).[58][59][60]

- Young, writing in 1817, states that Hutchinson gave up his business "40 years ago", whereas White states that up to 1787, he was still building ships, though in a slightly different area than when he started in 1763.[96][76]

- Barker and White refer to the yard as being spelt Langborne.[15][85] Others, such as Bebb and Young refer to it as Langbournes.[98]

- The Monkshaven sank some 133 miles (214 km) east of Montevideo whilst carrying coal from the United Kingdom to Valparaiso. The crew were rescued by a steam yacht called The Sunbeam owned by Earl Brassey.[103][104]

References

- Waters 2011, p. 38.

- "What's the Difference Between a 'Boat' and a 'Ship'?". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Kantharia, Rank. "7 Differences Between a Ship and a Boat". www.marineinsight.com. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Barker 2011, p. 18.

- Hall 2013, p. 13.

- "England's Historic Seascapes: Scarborough to Hartlepool". Archaeology Data Service. 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- Historic England. "Alum quarries and works 800m north of Sandsend Bridge (1018139)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Historic England. "Saltwick Nab alum quarries (1017779)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "Genuki: WHITBY, Yorkshire (North Riding)". www.genuki.org.uk. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Barker 2011, p. 22.

- "How alum shaped the Yorkshire coast". National Trust. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "Where I live, North Yorkshire: Coast Point 7 - Alum". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "Nostalgia: Ancient rivalry of two sea ports". The Scarborough News. 20 March 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Barker, Rosalin (2003). "10.8: Whitby". In Butlin, Robin A (ed.). Historical atlas of North Yorkshire. Otley: Westbury. p. 211. ISBN 1-84103-023-6.

- Barker 1990, p. 34.

- Barker 2011, p. 5.

- Young 1817, p. 548.

- Whitworth 2002, p. 214.

- Barker 2011, p. 35.

- "Parishes: Whitby | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Defoe, Daniel (1753). A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain ... Vol. 2. London: S Birt. p. 656. OCLC 852195558.

- Davis 2012, p. 61.

- Weatherill 1908, p. 26.

- Buglass & Brigham 2008, p. 32.

- "Whitby History". www.hmbarkendeavour.co.uk. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- "England's Historic Seascapes: Scarborough to Hartlepool". archaeologydataservice.ac.uk. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- Truss, Lynne (2016). The lunar cats. London: Penguin Books. p. 17. ISBN 9781780896724.

- Flanagan, Emily (20 September 2018). "Archaeologists may have found Captain Cook's Endeavour ship". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- Cornish, Anthony (2008). The voyages of Captain Cook : 101 questions and answers about the explorer and his three great scientific expeditions. London: Conway. p. 13. ISBN 9781844860609.

- Waters 1992, p. 162.

- Moore 2019, p. 47.

- Moore 2019, p. 260.

- Ossowski, Waldemar (2008). The General Carleton shipwreck, 1785 = Wrak statku General Carleton, 1785 (in Polish). Gdansk: Centralne Muzeum Morskie. p. 131. ISBN 9788392436010.

- Young 1817, p. 556.

- Lewis, Stephen (29 August 2011). "Turning tides of fortune of the North Yorkshire coast". York Press. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Young 1817, p. 557.

- Young 1840, pp. 207–208.

- Charlton 1779, p. 358.

- Bebb 2000, p. 15.

- Barker 1990, p. 35.

- Barker 2011, p. 90.

- Moore 2019, p. 19.

- MacMahon, Kenneth Austin (1964). "Roads and Turnpike Trusts in Eastern Yorkshire". East Yorkshire Local History Series. York: East Yorkshire Local History Society (18): 16–17. OCLC 562277081.

- MacMahon, Kenneth Austin (1964). "Roads and Turnpike Trusts in Eastern Yorkshire". East Yorkshire Local History Series. York: East Yorkshire Local History Society (18): 38–39. OCLC 562277081.

- "Scarborough Maritime Heritage Centre | Whitbys early history - a fishing town". www.scarboroughsmaritimeheritage.org.uk. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Jones 1982, pp. 149–152.

- "Point 1 - Shipbuilding". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Davis 2012, pp. 67–68.

- White, William (1840). History, gazetteer, and directory, of the East and North Ridings of Yorkshire. Sheffield: White. p. 502. OCLC 319907952.

- Browne 1946, p. 255.

- "Iron Shipbuilding at Whitby". The York Herald (9, 865). Column D. 27 December 1882. p. 6. OCLC 877360086.

- "Ship Building at Whitby". The Northern Echo (4, 628). Column F. 19 December 1884. p. 4. OCLC 56085065.

- "The Trade of Whitby in 1884". The York Herald (10, 475). Column D. 23 December 1884. p. 3. OCLC 877360086.

- Wilkinson, Colin (2016). Whitby between the wars. Stroud: Amberley. p. 8. ISBN 9781445662725.

- Browne 1946, p. 184.

- Simon, Jos (2015). The rough guide to Yorkshire (2 ed.). London: Rough Guides. p. 250. ISBN 9781409371045.

- White 1993, p. 66.

- Waters 2011, p. 25.

- White 1993, p. 69.

- Shaw, Bill Eglon (1974). Frank Meadow Sutcliffe, Hon. F.R.P.S. : Whitby and its people as seen by one of the founders of the naturalistic movement in photography. A selection of his work. Whitby: Sutcliffe Gallery. p. 15. ISBN 0-9503175-0-0.

- Browne 1946, p. 185.

- Fryer 1958, p. 250.

- Cook, Robin (2013). Whitby through time. Stroud: Amberley. p. 18. ISBN 9781848682184.

- Waters 1992, p. 145.

- Whitworth 2002, p. 250.

- Waters 2011, p. 44.

- "Ship breaking Industry". www.naval-history.net. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Barker 1990, p. 36.

- Weatherill 1908, p. 147.

- "Records of Barry's ship owners and shipbuilders of Whitby". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Whitworth, Alan (1998). Esk Valley Railway : a travellers' guide ; a description of the history and topography of the line between Whitby and Middlesbrough. Barnsley: Wharncliffe. p. 19. ISBN 1-871647-49-5.

- Robinson, Debbie. "University of Exeter". humanities.exeter.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Young 1840, pp. 243–244.

- Browne 1946, p. 180.

- "Records of Eskdale, Smales and Cato, Shipbuilders". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- White 1993, p. 70.

- "SUMMER ROSE - H358 - Yorkshire Coble - Hull (H) - Gallery". TrawlerPictures.net. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- "Heroes of the cruel sea". The Yorkshire Post. 27 October 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Fryer 1958, p. 251.

- "Around the US with the Orrs". The Whitby Gazette. 16 January 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- White 1993, p. 67.

- Moore 2019, p. 37.

- Waters 1992, p. 28.

- Young 1817, p. 549.

- White 1993, p. 68.

- "Scarborough Maritime Heritage Centre | History - 2". www.scarboroughsmaritimeheritage.org.uk. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Records of Eskdale, Smales and Cato, Shipbuilders". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Jones 1982, p. 445.

- Moore 2019, p. 39.

- Young 1840, p. 244.

- Minting, Stuart (29 March 2013). "Archaeologists investigate Captain Cook shipyard". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Historic England. "Whitby Engine Shed and Engine Stable Cottage (Grade II) (1239954)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Whitworth 2002, p. 215.

- Jones 1982, p. 150.

- Jones 1982, p. 132.

- Young 1817, p. 550.

- "From Boom to Bust". berwickshipyard.com. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Bebb 2000, p. 17.

- White 1993, p. 71.

- Paine, Lincoln Paxton (2000). Ships of discovery and exploration. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co. p. 41. ISBN 0-395-98415-7.

- "Motor Vessel SUMMER ROSE built by Parkol Marine Engineering Ltd., Whitby in 2018 for John McAlister, Oban, Fishing Vessel". www.teesbuiltships.co.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Whitworth 2002, p. 216.

- "WRECKSITE - MONKSHAVEN BARQUE - BARK 1873-1876". www.wrecksite.eu. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Shipwrecks and Loss of Life". The Manchester Times (987). Column E. 11 November 1876. p. 3.

- "Shipbuilding family's treasures up for sale". The Yorkshire Post. 2 April 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "A part of town's history". The Whitby Gazette. 28 March 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Whitworth 2002, p. 248.

- Ritchie 1992, p. 153.

- "Thomas Turnbull and Son - Graces Guide". www.gracesguide.co.uk. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Coaling, docking, and repairing facilities of the ports of the world. Washington: Office of Naval Intelligence. 1900. p. 275. OCLC 818431655.

- Commercial relations of the United States with foreign countries during the years 1887 and 1888. : (Annual reports from the consuls of the United States on the commerce, manufactures, industries, etc., of their several districts for the above years.) (4 ed.). Washington: Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce. 1888. p. 277. OCLC 12016620.

- "Genuki: Transcript of the entry for the Post Office, professions and trades for WHITBY in Bulmer's Directory of 1890., Yorkshire (North Riding)". www.genuki.org.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Whitby Shipbuilding & Engineering Co Ltd". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "National Shipbuilders Security - Graces Guide". www.gracesguide.co.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Jones, Leslie (1957). Shipbuilding in Britain : mainly between the two World Wars. Cardiff`: University of Wales Press. pp. 133–137. OCLC 1017775683.

- "Motor Vessel WHITBY built by Whitby Shipbuilding & Engineering Co. Ltd. in 1960 for Tees Conservancy Commissioners, Middlesbrough, Launch". www.teesbuiltships.co.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Fryer 1958, p. 252.

- Browne 1946, p. 179.

- "Records of Eskdale, Smales and Cato, Shipbuilders". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Brannigan, Caroline (21 September 2003). "Buoyed by the bay of plenty". The Times. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- "Work starts on housing development". The Whitby Gazette. 7 May 2002. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Davis 2012, p. 62.

- Waters 2011, p. 93.

Sources

- Barker, Rosalin (1990). The Book of Whitby. Oxfordshire: Barracuda Books. ISBN 0-86023-462-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barker, Rosalin (2011). The Rise of an Early Modern Shipping Industry; Whitby's Golden Fleet 1600-1750. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-631-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bebb, Prudence (2000). Life in Regency Whitby 1811–1820. York: William Sessions. ISBN 1-85072-257-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Browne, Horace Baker (1946). Chapters of Whitby history, 1823-1946 : the story of Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society and of Whitby Museum. Hull: Brown & Sons. OCLC 74365993.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buglass, J & Brigham, T (June 2008). Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment East Yorkshire; Whitby to Reighton (PDF). historicengland.org.uk (Report). Hull: Humber Field Archaeology. Retrieved 21 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Charlton, Lionel (1779). The history of Whitby : and of Whitby Abbey. Collected from the original records of the Abbey, and other authentic memoirs, never before made public. London: A Ward. OCLC 520863806.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Ralph (2012). The rise of the English shipping industry in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Newfoundland: Internatonal Maritime Economic History Association. ISBN 978-0-9864973-8-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fryer, D H (1958). "Whitby Harbour". In Daysh, George Henry John (ed.). A survey of Whitby and the surrounding area. Eton: Shakespeare Head Press. OCLC 869799013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, Chris (January 2013). Whitby Conservation Area – Character Appraisal & Management Plan (PDF) (Report). Scarbrough: Scarborough Borough Council. Retrieved 19 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Stephanie Karen (1982). A Maritime History of the Port of Whitby, 1700-1914 (PDF) (Report). London: University College London. Retrieved 28 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Peter (2019). Endeavour. The Ship and the Attitude That Changed the World. London: PenGuin Books. ISBN 978-1-78470-392-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ritchie, L A, ed. (1992). The Shipbuilding Industry; a Guide to Historical Records. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3805-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waters, Colin (1992). Whitby; a Pictorial History. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-848-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waters, Colin (2011). A History of Whitby & its Place Names. Stroud: Amberley. ISBN 978-1-4456-0429-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, Andrew (1993). A History of Whitby. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-842-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weatherill, Richard (1908). The ancient port of Whitby and its shipping : with some subjects of interest connected therewith. Whitby: Horne & Son. OCLC 153801738.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whitworth, Alan (2002). An A to Z of Whitby History. Whitby: Culva. ISBN 1-871150-05-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, George (1817). A history of Whitby, and Streoneshalh abbey ; with a statistical survey of the vicinity to the distance of twenty-five miles. Whitby: Clark & Medd. OCLC 1046520071.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, George (1840). A picture of Whitby and its environs (2 ed.). Whitby: Horne & Richardson. OCLC 931179820.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shipbuilding in Whitby. |