Deutscher Michel

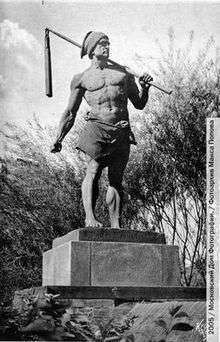

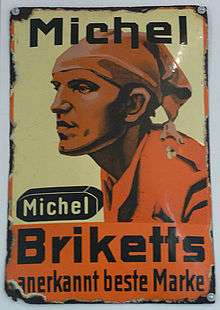

Der Deutsche Michel ("Michael the German") is a figure representing the national character of the German people, rather as John Bull represents the English. He originated in the first half of the 19th century.

Overview

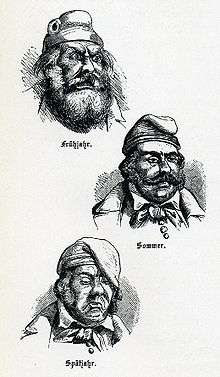

Michel differs from figures that serve as personifications of the nation itself, as Germania did the German nation and Marianne the French, in that he represents the German people.[1] He is usually depicted wearing a nightcap and nightgown, sometimes in the colours of the German flag, and represents the Germans' conception of themselves, especially in his easy-going nature and Everyman appearance. In any event, the nightgown and the night cap, which have been present in all pictorial representations of the German Michel - the first ones dating from the first half of the nineteenth century - are also interpreted in a way that the German Michel is, in fact, a rather naive and gullible person, not prone, for example, to question the authority of the government. On the contrary, he prefers a decent, plain and quiet lifestyle.

Over the centuries, the character traits attributed to the German Michel were subject to some change. The British historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote the most notable aspect of Deutscher Michel as portrayed in Imperial Germany was that: "The point about Deutscher Michel is that his image stressed both the innocence and simple-mindedness so readily exploited by cunning foreigners, and the physical strength he could mobilize to frustrate their knavish tricks and conquests when finally roused. 'Michel' seems to have been essentially an anti-foreign image".[1] The central problem of creating a national identity in the newly unified Reich was all of the various German states had their own histories and traditions, none of which could be used as a symbol to appeal to everybody, leading to a situation where Hobsbawam noted: "Like many another liberated' people', 'Germany' was more easily defined by what it was against than in any way".[2] The xenophobic tendency to the Deutscher Michel character in the 19th century, whose innocence stands in marked contrast to the cunning and devious foreigners who are always trying to trick him, reflected the fact it was more easy to define the Reich in terms of what it was against rather than it was for.[1] In this regard, Deutscher Michel was very different from Marianne who was defined in a more positive way as a symbol of the republic and its values.[1]

A typical cartoon featuring Deutscher Michel occurred in the May 1914 edition of the magazine Kladderadatsch where Deutscher Michel is working happily in his garden with a seductive and voluptuous Marianne on one side and a brutish muzhik (Russian peasant) on the other; the message of the cartoon was that France should not be allied to Russia, and would be better off allied to Germany, since Deutscher Michel with his well tended garden is clearly a better potential husband than the vodka-drinking muzhik whose garden is a disorderly disaster.[3] To further reinforce the point, Deutscher Michel is pouring cold water on two chickens in a cage whose initials stand for Alsace-Lorraine, meaning that Germany can pour cold water on France's hopes of taking back Alsace-Lorriane anytime it wants.[4] The caption has Deutscher Michel saying that he wants peace, but if his neighbors want war, then they will get it, reflecting the fact that Michel for all his good-natured and easy-going ways, is utterly ferocious when angered.[4]

In German, Michel is also the short form of Michael, though quite rare today.

See also

References

- Hobsbawm 1983, p. 276.

- Hobsbawm 1983, p. 278.

- Klahr 2011, p. 544-545.

- Klahr 2011, p. 545.

Sources

- Eric Hobsbawm, "Mass-Producing Traditions: Europe, 1870–1914," in Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, eds., The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge, 1983)

- Klahr, Douglas (2011). "Symbiosis between Caricature and Caption at the Outbreak of War: Representations of the Allegorical Figure Marianne in "Kladderadatsch"". Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte. 74 (1). pp. 437–558.