Saint Catherine's Monastery

Saint Catherine's Monastery (Arabic: دير القدّيسة كاترين; Greek: Μονὴ τῆς Ἁγίας Αἰκατερίνης), officially "Sacred Monastery of the God-Trodden Mount Sinai" (Greek: Ιερά Μονή του Θεοβαδίστου Όρους Σινά), is an Eastern Orthodox monastery located on the Sinai Peninsula, at the mouth of a gorge at the foot of Mount Sinai, near the town of Saint Catherine, Egypt. The monastery is named after Catherine of Alexandria.

The monastery, with Willow Peak (traditionally considered Mount Horeb) in the background | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Church of Sinai |

| Denomination | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Established | AD 565 |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Justinian I |

| Site | |

| Location | Saint Catherine, South Sinai Governorate, Egypt |

| Coordinates | 28°33′20″N 33°58′34″E |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Saint Catherine Area |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 2002 (26th session) |

| Reference no. | 954 |

| State Party | Egypt |

| Region | Arab States |

The monastery is controlled by the autonomous Church of Sinai, part of the wider Greek Orthodox Church, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[1]

Built between 548 and 565, the monastery is one of the oldest working Christian monasteries in the world.[2] The site contains the world's oldest continually operating library,[3] possessing many unique books including the Syriac Sinaiticus and, until 1859, the Codex Sinaiticus.[4][5]

Christian traditions

During her imprisonment more than 200 people came to see her, including Maxentius' wife, Valeria Maximilla; all converted to Christianity and were subsequently martyred.[6] The furious emperor condemned Catherine to death on a spiked breaking wheel, but, at her touch, it shattered.[7] Maxentius ordered her to be beheaded. Catherine herself ordered the execution to commence. A milk-like substance rather than blood flowed from her neck.[8]

Although it is commonly known as Saint Catherine's, the monastery's full official name is the Sacred Monastery of the God-Trodden Mount Sinai. The patronal feast of the monastery is the Feast of the Transfiguration. The monastery has become a favorite site of pilgrimage.

History

_p057_MT._SINAI_OR_JEBEL_MUSA.jpg)

The oldest record of monastic life at Sinai comes from the travel journal written in Latin by a woman named Egeria about 381–384.[9] She visited many places around the Holy Land and Mount Sinai, where, according to the Old Testament, Moses received the Ten Commandments from God.[10]

The monastery was built by order of Emperor Justinian I (reigned 527–565), enclosing the Chapel of the Burning Bush (also known as "Saint Helen's Chapel") ordered to be built by Empress Consort Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, at the site where Moses is supposed to have seen the burning bush.[11] The living bush on the grounds is purportedly the one seen by Moses.[12] Structurally the monastery's king post truss is the oldest known surviving roof truss in the world.[13] The site is sacred to Christianity, Islam, and Judaism.[14]

A mosque was created by converting an existing chapel during the Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171), which was in regular use until the era of the Mamluk Sultanate in the 13th century and is still in use today on special occasions. During the Ottoman Empire, the mosque was in desolate condition; it was restored in the early 20th century.[15]

During the seventh century, the isolated Christian anchorites of the Sinai were eliminated: only the fortified monastery remained. The monastery is still surrounded by the massive fortifications that have preserved it. Until the twentieth century, access was through a door high in the outer walls. From the time of the First Crusade, the presence of Crusaders in the Sinai until 1270 spurred the interest of European Christians and increased the number of intrepid pilgrims who visited the monastery. The monastery was supported by its dependencies in Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Crete, Cyprus and Constantinople.

The monastery, along with several dependencies in the area, constitute the entire Church of Sinai, which is headed by an archbishop, who is also the abbot of the monastery. The exact administrative status of the church within the Eastern Orthodox Church is ambiguous: by some, including the church itself,[16] it is considered autocephalous,[17][18] by others an autonomous church under the jurisdiction of the Greek Orthodox Church of Jerusalem.[19] The archbishop is traditionally consecrated by the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem; in recent centuries he has usually resided in Cairo. During the period of the Crusades which was marked by bitterness between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, the monastery was patronized by both the Byzantine emperors and the rulers of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and their respective courts.

On April 18, 2017, an attack by the Islamic State group at a checkpoint near the Monastery killed one policeman and injured three police officers.[20]

Manuscripts and icons

The library, founded sometime between 548 and 565, is the oldest continuously operating library in the world.[21]The monastery library preserves the second largest collection of early codices and manuscripts in the world, outnumbered only by the Vatican Library.[22] It contains Greek, Georgian, Arabic, Coptic, Hebrew, Armenian, Aramaic and Caucasian Albanian texts.

In May 1844 and February 1859, Constantin von Tischendorf visited the monastery for research and discovered the Codex Sinaiticus, dating from the 4th Century, at the time the oldest almost completely preserved manuscript of the Bible. The finding from 1859 left the monastery in the 19th century for Russia, in circumstances that had been long disputed. But in 2003 Russian scholars discovered the donation act for the manuscript signed by the Council of Cairo Metochion and Archbishop Callistratus on 13 November 1869. The monastery received 9000 rubles as a gift from Tsar Alexander II of Russia.[23] The Codex was sold by Stalin in 1933 to the British Museum and is now in the British Library, London, where it is on public display. Prior to September 1, 2009, a previously unseen fragment of Codex Sinaiticus was discovered in the monastery's library.[24][25]

In February 1892, Agnes Smith Lewis identified a palimpsest in St Catherine's library that became known as the Syriac Sinaiticus and is still in the Monastery's possession. Agnes and her sister Margaret Dunlop Gibson returned with a team of scholars that included J. Rendel Harris, to photograph and transcribe the work in its entirety.[26] As the manuscript predates the Codex Sinaiticus, it became crucial in understanding the history of the New Testament.

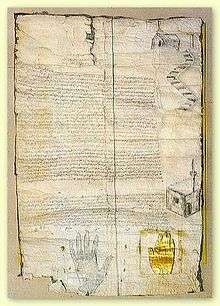

The Monastery also has a copy of the Ashtiname of Muhammad, in which the Islamic prophet Muhammad is claimed to have bestowed his protection upon the monastery.[27]

Additionally, the monastery houses a copy of Mok'c'evay K'art'lisay, a collection of supplementary books of the Kartlis Cxovreba, dating from the 9th century.[28]

The most important manuscripts have since been filmed or digitized, and so are accessible to scholars. With planning assistance from Ligatus, a research center of the University of the Arts London, the library was extensively renovated, reopening at the end of 2017.[29][30]

Sinai Palimpsests Project

Since 2011, a team of imaging scientists and scholars from the U.S. and Europe has studied the library's collection of palimpsests.[11][31] The project's original leaders were history professor Claudia Rapp of the University of California, Los Angeles, and Michael Phelps of the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library.[31] Images from the project are freely available for research at the UCLA Online Library.[32]

Palimpsests are notable for having been reused one or more times over the centuries. Since parchment was expensive, monks would erase certain texts with lemon juice and write over them.[3][33] Though the original texts were once assumed to be lost,[9] the scholars used narrowband multispectral imaging techniques and technologies to reveal features that were difficult to see with the human eye, including ink residues and small grooves in the parchment.[11][22] Each page took approximately eight minutes to scan completely.[22]

As of June 2018, at least 170 palimpsests were identified, with over 6,800 pages of texts recovered.[22] Many of these newer finds were discovered in a secluded storage area in 1975.[11] Highlights include "108 pages of previously unknown Greek poems and the oldest-known recipe attributed to the Greek physician Hippocrates," as well as insight into dead languages such as Caucasian Albanian and Christian Palestinian Aramaic.[33][34] These images have subsequently been digitized and distributed online for scholarly use.[1][9]

Works of art

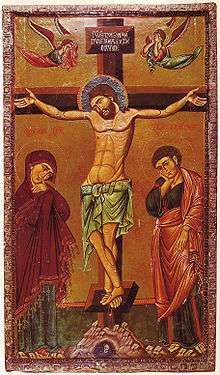

The complex houses irreplaceable works of art: mosaics, the best collection of early icons in the world, many in encaustic, as well as liturgical objects, chalices and reliquaries, and church buildings. The large icon collection begins with a few dating to the 5th (possibly) and 6th centuries, which are unique survivals; the monastery having been untouched by Byzantine iconoclasm, and never sacked. The oldest icon on an Old Testament theme is also preserved there. A project to catalogue the collections has been ongoing since the 1960s. The monastery was an important centre for the development of the hybrid style of Crusader art, and still retains over 120 icons created in the style, by far the largest collection in existence. Many were evidently created by Latins, probably monks, based in or around the monastery in the 13th century.[35]

Icons

Icon of the enthroned Virgin and Child with saints and angels, 6th century

Icon of the enthroned Virgin and Child with saints and angels, 6th century The oldest known icon of Christ Pantocrator, encaustic on panel

The oldest known icon of Christ Pantocrator, encaustic on panel Crucifixion, 13th century

Crucifixion, 13th century Holy doors

Holy doors Madonna and Child, 13th century

Madonna and Child, 13th century 13th century Byzantine icon of Saint Michael the Archangel

13th century Byzantine icon of Saint Michael the Archangel Transfiguration, 12th century

Transfiguration, 12th century

Emperor John VIII Palaiologos

Emperor John VIII Palaiologos Icon of Saint Catherine of Alexandria

Icon of Saint Catherine of Alexandria The monastery, 18th century

The monastery, 18th century

Historical images

1762

1762_p145_THE_CONVENT_MOUNT_SINANI.jpg) 1855

1855_b_060.jpg) 1861

1861 1892

1892

Saint Catherine's Foundation

The Saint Catherine's Foundation is a UK-based non-profit organization that aims to preserve the monastery. The conservation of its architectural structures, paintings, and books comprise much of the Foundation's purpose. The Saint Catherine's Foundation works with its academic partner, the Ligatus Research Center at the University of the Arts, London, to raise awareness of the monastery's unique cultural significance via lectures, books and articles.[36] Founded on November 2, 2007 at the Royal Geographical Society in London needs new funds for the conservation workshop, digitization studio and full complement of conservation boxes designed to protect the most vulnerable manuscripts of the monastery. About 2000 manuscripts should be stored in boxes.

See also

- Archbishop of Mount Sinai and Raithu

- Ashtiname of Muhammad

- Charnel House

- Desert fathers

- Gregory of Sinai

- Ladder of Divine Ascent

- Oldest churches in the world

- Poustinia

- Kurt Weitzmann

References

- Georgiou, Aristos (December 20, 2017). "These spectacular ancient texts were lost for centuries, and now they can be viewed online". International Business Times. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018.

- Din, Mursi Saad El et al.. Sinai: The Site & The History: Essays. New York: New York University Press, 1998. 80. ISBN 0814722032

- Gray, Richard (August 9, 2017). "The Invisible Poems Hidden in One of the World's Oldest Libraries". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018.

- Schrope, Mark (June 1, 2015). "Medicine's Hidden Roots in an Ancient Manuscript". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- Jules Leroy; Peter Collin (2004). Monks and Monasteries of the Near East. Gorgias Press. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-59333-276-1.

- "Saint Catherine of Alexandria". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- Clugnet 1908.

- Morton 1841, p. 133.

- Marchant, Jo (December 11, 2017). "Archaeologists Are Only Just Beginning to Reveal the Secrets Hidden in These Ancient Manuscripts". Smithsonian. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Pilgrimage of Etheria text at ccel.org

- Schrope, Mark (September 6, 2012). "In the Sinai, a global team is revolutionizing the preservation of ancient manuscripts". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- "Is the Burning Bush Still Burning?". Friends of Mount Sinai Monastery. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Feilden, Bernard M.. Conservation of historic buildings. 3rd ed. Oxford: Architectural Press, 2003. 51. ISBN 0750658630

- "The Monastery". St-Katherine-net. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- "Saint Catherine Area".

- The official Website describes the Church as "διοικητικά "αδούλωτος, ασύδοτος, ακαταπάτητος, πάντη και παντός ελευθέρα, αυτοκέφαλος" or "administratively 'free, loose, untresspassable, free from anyone at any time, autocephalous'" (see link below)

- Weitzmann, Kurt, in: Galey, John; Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine, p. 14, Doubleday, New York (1980) ISBN 0-385-17110-2

- Ware, Kallistos (Timothy) (1964). "Part I: History". The Orthodox Church. Penguin Books. Retrieved 2007-07-14. Under Introduction Bishop Kallistos says that Sinai is "autocephalous"; under The twentieth century, Greeks and Arabs he states that "There is some disagreement about whether the monastery should be termed an 'autocephalous' or merely an 'autonomous' Church."

- The Orthodox Church of Mount Sinai CNEWA Canada, "A papal agency for humanitarian and pastoral support" Archived May 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Deadly attack near Egypt's old monastery". BBC News. April 19, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Esparza, Daniel. "The library of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai has never closed its doors". Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- Macdonald, Fleur (June 13, 2018). "Hidden writing in ancient manuscripts". BBC News. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018.

- The History of the acquisition of the Sinai Bible by the Russian Government in the context of recent findings in Russian archives (english Internetedition). The article from A.V. Zakharova was first published in Montfaucon. Études de paléographie, de codicologie et de diplomatique, Moscow–St.Petersburg, 2007, pp. 209–66) see also Alexander Schick, Tischendorf und die älteste Bibel der Welt. Die Entdeckung des Codex Sinaiticus im Katharinenkloster (Tischendorf and the oldest Bible in the world – The discovery of the Codex Sinaiticus in St. Catherine's Monastery), Muldenhammer 2015, pp. 123–28, 145–55.

- "Fragment from world's oldest Bible found hidden in Egyptian monastery". The Independent, 2 Sept, 2009.

- "Oldest known Bible to go online". BBC News, 3 August 2005.

- Soskice, Janet (2009). "Chapter 14". The Sisters of Sinai: How two lady adventurers discovered the hidden gospels. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-1-4000-3474-1.

- Brandie Ratliff, "The monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai and the Christian communities of the Caliphate." Sinaiticus. The bulletin of the Saint Catherine Foundation (2008) Archived 2015-02-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- Kavtaradze, Giorgi (2001). "THE GEORGIAN CHRONICLES AND THE RAISON D'ÈTRE OF THE IBERIAN KINGDOM". JOURNAL OF HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE ANCIENT WORLD.

- http://www.ligatus.org.uk/stcatherines/node/3877 Retrieved 20 May 2018

- "Egypt Reopens Ancient Library at St. Catherine Monastery". Voice of America. Retrieved 2019-11-23.

- Hsing, Crystal (April 15, 2011). "Scholars use tech tools to reveal texts". Daily Bruin. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- "Sinai Palimpsests Research Site". Archived from the original on 2018-11-03.

- Farrell, Jeff (August 28, 2017). "Scientists discover languages that haven't been used since the dark ages". The Independent. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018.

- Katz, Brigit (September 5, 2017). "Lost Languages Discovered in One of the World's Oldest Continuously Run Libraries". Smithsonian. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Kurt Weitzmann in The Icon, Evans Brothers Ltd, London (1982), pp. 201–07 (trans. of Le Icone, Montadori 1981), ISBN 0-237-45645-1

- "St Catherine Monastery – United Kingdom – Saint Catherine Foundation". St Catherine Monastery – United Kingdom – Saint Catherine Foundation.

Further reading

- The Monastery of St Catherine. Oriana Baddeley and Earleen Brunner. 1996. pp. 120 pages with 79 colour illustrations. ISBN 978-0-9528063-0-1.

- Böttrich, Christfried (2011). Der Jahrhundertfund. Entdeckung und Geschichte des Codex Sinaiticus (The Discovery of the Century. Discovery and history of Codex Sinaiticus). Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt. ISBN 978-3-374-02586-2.

- Forsyth, G. H.; Weitzmann, K. (1973). The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai - The Church and Fortress of Justinian: Plates. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-472-33000-4.

- Porter, Stanley E. (2015). Constantine Tischendorf. The Life and Work of a 19th Century Bible Hunter. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-5676-5803-6.

- Schick, Alexander (2015). Tischendorf und die älteste Bibel der Welt - Die Entdeckung des CODEX SINAITICUS im Katharinenkloster (Tischendorf and the oldest Bible in the world. The discovery of the Codex Sinaiticus in St. Catherine's Monastery. Biography cause of the anniversary of the 200th birthday of Tischendorf with many unpublished documents from his estate. These provide insight into previously unknown details of the discoveries and the reasons behind the donation of the manuscript. Recent research on Tischendorf and the Codex Sinaiticus and its significance for New Testament Textual Research). Muldenhammer: Jota. ISBN 978-3-935707-83-1.

- Soskice, Janet (1991). Sisters of Sinai: How Two Lady Adventurers Found the Hidden Gospels. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-1-4000-3474-1.

- Sotiriou, G. and M. (1956–1958). Icones du Mont Sinaï. 2 vols (plates and texts). Collection de L'Institut francais d'Athènes 100 and 102. Athens.

- Weitzmann, K. (1976). The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mihnt Sinai: The Icons, Volume I: From the Sixth to the Tenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Weitzmann, K.; Galavaris, G. (1991). The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai. The Illuminated Greek Manuscripts, Volume I. From the Ninth to the Twelfth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03602-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai. |

- Official Website of the Holy Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai

- Saint Catherine Area/ World Heritage Listing on UNESCO's Website

- Saint Catherine Foundation

- St. Catherine's Monastery, Sinai, Egypt

- St Catherine Project (digitisation) video

- Holy Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai Getty exhibit

- Early Icons from Sinai, Belmont U

- St. Catherine's Monastery (Sinai) (OrthodoxWiki article)

- The text of the Charter from Muhammad can be read here or here.

- At a Mountain Monastery, Old Texts Gain Digital Life article from New York Times

- Information about the town of St. Catherine

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Prophet Muhammad's Letter to Monks of St. Catharine Monastery

- More on Saint Catherine's Monastery and Mount Sinai

- Caucasian Albanian Alphabet: Ancient Script Discovered in the Ashes [St. Catherine's], Azerbaijan International, Vol. 11:3 (Autumn 2003), pp. 38–41.

- Article on the Orthodox Church of Mount Sinai by Ronald Roberson on the CNEWA web site

- The Albanian Script: The Process – How Its Secrets Were Revealed [St. Catherine's], Azerbaijan International, Vol. 11:3 (Autumn 2003), pp. 44–51.

- Map showing the Monastery, 18th century. Eran Laor Cartographic Collection. The National Library of Israel