SMS Blücher

SMS Blücher[lower-alpha 1] was the last armored cruiser built by the German Empire. She was designed to match what German intelligence incorrectly believed to be the specifications of the British Invincible-class battlecruisers. Blücher was larger than preceding armored cruisers and carried more heavy guns, but was unable to match the size and armament of the battlecruisers which replaced armored cruisers in the British Royal Navy and German Imperial Navy (Kaiserliche Marine). The ship was named after the Prussian Field Marshal Gebhard von Blücher, the commander of Prussian forces at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

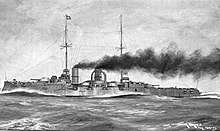

SMS Blücher in 1912 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Blücher |

| Namesake: | Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher[1] |

| Builder: | Kaiserliche Werft, Kiel |

| Laid down: | 21 February 1907 |

| Launched: | 11 April 1908 |

| Commissioned: | 1 October 1909 |

| Fate: | Sunk during the Battle of Dogger Bank, 24 January 1915 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Armored cruiser |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 161.8 m (530 ft 10 in) overall |

| Beam: | 24.5 m (80 ft 5 in) |

| Draft: | 8.84 m (29 ft) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 25.4 knots (47.0 km/h; 29.2 mph) |

| Range: |

|

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Blücher was built at the Kaiserliche Werft shipyard in Kiel between 1907 and 1909, and commissioned on 1 October 1909. The ship served in the I Scouting Group for most of her career, including the early portion of World War I. She took part in the operation to bombard Yarmouth and the raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby in 1914.

At the Battle of Dogger Bank on 24 January 1915, Blücher was slowed significantly after being hit by gunfire from the British battlecruiser squadron under the command of Vice Admiral David Beatty. Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper, the commander of the German squadron, decided to abandon Blücher to the pursuing enemy ships in order to save his more valuable battlecruisers. Under heavy fire from the British ships, she was sunk, and British destroyers began recovering the survivors. However, the destroyers withdrew when a German zeppelin began bombing them, mistaking the sinking Blücher for a British battlecruiser. The number of casualties is unknown, with figures ranging from 747 to around 1,000. Blücher was the only warship lost during the battle.

Design

German armored cruisers—referred to as Grosse Kreuzer (large cruisers)—were designed for several tasks. The ships were designed to engage the reconnaissance forces of rival navies, as well as fight in the line of battle.[2] The earliest armored cruiser—Fürst Bismarck—was rushed through production specifically to be deployed to China to assist in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. Subsequent armored cruisers—with the exception of the two Scharnhorst-class ships—served with the fleet in the reconnaissance force.[3]

On 26 May 1906, the Reichstag authorized funds for Blücher, along with the first two Nassau-class battleships. Though the ship would be much larger and more powerful than previous armored cruisers, Blücher retained that designation in an attempt to conceal its more powerful nature.[4] The ship was ordered under the provisional name "E".[lower-alpha 2] Her design was influenced by the need to match the armored cruisers which Britain was known to be building at the time. The Germans expected these new British ships to be armed with six or eight 9.2 in (23 cm) guns.[5] In response, the German navy approved a design with twelve 21 cm (8.3 in) guns in six twin turrets. This was significantly more firepower than that of the Scharnhorst class, which carried only eight 21 cm guns.[6]

One week after the final decision was made to authorize construction of Blücher, the German naval attache obtained the actual details of the new British ships, called the Invincible class. In fact, HMS Invincible carried eight 30.5 centimetres (12 in) guns of the same type mounted on battleships. It was soon recognized that these ships were a new type of warship, which eventually came to be classified as the battlecruiser. When the details of the Invincible class came to light, it was too late to redesign Blücher, and there were no funds for a redesign, so work proceeded as scheduled.[7] Blücher was therefore arguably obsolete even before her construction started, and was rapidly surpassed by the German Navy's battlecruisers, the first of which (Von der Tann) was ordered in 1907.[8] Despite this, Blücher was typically deployed with the German battlecruiser squadron.[5][lower-alpha 3]

General characteristics

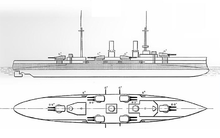

Blücher was 161.1 m (528 ft 7 in) long at the waterline and 161.8 m (530 ft 10 in) long overall. The ship had a beam of 24.5 m (80 ft 5 in), and with the anti-torpedo nets mounted along the sides of the ship, the beam increased to 25.62 m (84 ft 1 in). Blücher had a draft of 8.84 m (29 ft) forward, but slightly less aft, at 8.56 m (28 ft 1 in). The ship displaced 15,842 t (15,592 long tons) at her designed weight, and up to 17,500 t (17,200 long tons) at full load. Her hull was constructed with both transverse and longitudinal steel frames and she had thirteen watertight compartments and a double bottom that ran for approximately 65 percent of the length of the hull.[9]

Documents from the German naval archives generally indicate satisfaction with Blücher's minor pitch and gentle motion at sea.[9] However, she suffered from severe roll, and with the rudder hard over, she heeled over up to 10 degrees from the vertical and lost up to 55 percent of her speed. Blücher's metacentric height was 1.63 m (5 ft 4 in). The ship had a standard crew of 41 officers and 812 enlisted men, with an additional 14 officers and 62 sailors when she served as a squadron flagship. She carried a number of smaller vessels, including two picket boats, three barges, two launches, two yawls, and one dinghy.[9]

Propulsion

Blücher was equipped with three vertical, 4-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines. Each engine drove a screw propeller, the center screw being 5.3 m (17 ft 5 in) in diameter, while the outer two screws were slightly larger, at 5.6 m (18 ft 4 in) in diameter. The ship had a single rudder with which to steer. The three engines were segregated in individual engine rooms. Steam was provided by eighteen coal-fired, marine-type water-tube boilers, which were also divided into three boiler rooms. Electrical power for the ship was supplied by six turbo-generators that provided up to 1,000 kilowatts, rated at 225 volts.[9]

The ship had a designed maximum speed of 24.5 knots (45.4 km/h; 28.2 mph), but during her trials, she achieved 25.4 knots (47.0 km/h; 29.2 mph). The ship was designed to carry 900 t (890 long tons) of coal, though voids in the hull could be used to expand the fuel supply to up to 2,510 t (2,470 long tons) of coal. This provided a cruising radius of 6,600 nautical miles (12,200 km; 7,600 mi) at a cruising speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). At a speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), her range was cut down to 3,250 nmi (6,020 km; 3,740 mi).[9] The highest power ever achieved by a reciprocating engine warship was the 37,799 indicated horsepower (28,187 kW) produced by Blücher on her trials in 1909.[10]

Armament

Blücher was equipped with twelve 21 cm (8.27 in) SK L/45[lower-alpha 4] quick-firing guns in six twin turrets, one pair fore and one pair aft, and two pairs in wing turrets on either side of the superstructure. The guns were supplied with a total of 1,020 shells, or 85 rounds per gun.[9] Each shell weighed 108 kg (238 lb), and was 61 cm (24 in) in length. The guns could be depressed to −5° and elevated to 30°, providing a maximum range of 19,100 m (20,900 yd).[9] Their rate of fire was 4–5 rounds per minute.[12]

The ship had a secondary battery of eight 15 cm (5.91 in) quick-firing guns mounted in MPL C/06 casemates,[14] four centered amidships on either side of the vessel.[9] These guns could engage targets out to 13,500 m (14,800 yd).[12] They were supplied with 1320 rounds, for 165 shells per gun, and had a sustained rate of fire of 5–7 rounds per minute. The shells were 45.3 kg (99.9 lb),[14] and were loaded with a 13.7 kg (30.2 lb) RPC/12 propellant charge in a brass cartridge. The guns fired at a muzzle velocity of 835 m (2,740 ft) per second,[12] and were expected to fire around 1,400 shells before they needed to be replaced.

Blücher was also armed with sixteen 8.8 cm (3.46 in) SK L/45 quick-firing guns, placed in both casemates and pivot mounts. Four of these guns were mounted in casemates near the bridge, four in casemates in the bow, another four in casemates at the stern, and the remaining four were mounted in pivot mounts in the rear superstructure. They were supplied with a total of 3,200 rounds, or 200 shells per gun,[9] and could fire at a rate of 15 shells per minute. Their high explosive shells weighed 10 kg (22 lb),[14] and were loaded with a 3 kg (6.6 lb) RPC/12 propellant charge. These guns had a life expectancy of around 7,000 rounds. The guns had a maximum range of 10,700 m (11,700 yd).[14]

Blücher was also equipped with four 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes. One was placed in the bow, one in the stern, and the other two were placed on the broadside, all below the waterline. The ship carried a total of 11 torpedoes.[9] The torpedoes carried a 110 kg (240 lb) warhead and had two speed settings, which affected the range. At 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph), the weapon had a range of 2,000 m (2,200 yd) and at 36 knots (67 km/h; 41 mph), the range was reduced to 1,500 m (1,600 yd).[14]

Armor

As with other German capital ships of the period, Blücher was equipped with Krupp cemented armor. The armored deck was between 5–7 cm (2.0–2.8 in) in thickness; more important areas of the ship were protected with thicker armor, while less critical portions of the deck used the thinner armor.[9] The armored belt was 18 cm (7.1 in) thick in the central portion of the ship where propulsion machinery, ammunition magazines, and other vitals were located, and tapered to 8 cm (3.1 in) in less important areas of the hull. The belt tapered down to zero at either end of the ship. Behind the entire length of the belt armor was an additional 3 cm (1.2 in) of teak. The armored belt was supplemented by a 3.5 cm (1.4 in) torpedo bulkhead,[9] though this only ran between the forward and rear centerline gun turrets.[16]

The forward conning tower was the most heavily armored part of the ship. Its sides were 25 cm (9.8 in) thick and it had a roof that was 8 cm thick. The rear conning tower was significantly less well armored, with a roof that was 3 cm thick and sides that were only 14 cm (5.5 in) thick. The central citadel of the ship was protected by 16 cm (6.3 in) armor. The main battery turrets were 8 cm thick in their roofs, and had 18 cm sides. The 15 cm turret casemates were protected by 14 cm of armor.[9]

Service history

Blücher was launched on 11 April 1908 and commissioned into the fleet on 1 October 1909. She served as a training ship for naval gunners starting in 1911. In 1914, she was transferred to the I Scouting Group along with the newer battlecruisers Von der Tann, Moltke, and the flagship Seydlitz.[9] The first operation in which Blücher took part was an inconclusive sweep into the Baltic Sea against Russian forces. On 3 September 1914, Blücher, along with seven pre-dreadnought battleships of the IV Squadron, five cruisers, and 24 destroyers sailed into the Baltic in an attempt to draw out a portion of the Russian fleet and destroy it. The light cruiser Augsburg encountered the armored cruisers Bayan and Pallada north of Dagö (now Hiiumaa) island. The German cruiser attempted to lure the Russian ships back towards Blücher so that she could destroy them, but the Russians refused to take the bait and instead withdrew to the Gulf of Finland. On 9 September, the operation was terminated without any major engagements between the two fleets.[17]

On 2 November 1914, Blücher—along with the battlecruisers Moltke, Von der Tann, and Seydlitz, and accompanied by four light cruisers, left the Jade Bight and steamed towards the English coast.[18] The flotilla arrived off Great Yarmouth at daybreak the following morning and bombarded the port, while the light cruiser Stralsund laid a minefield. The British submarine HMS D5 responded to the bombardment, but struck one of the mines laid by Stralsund and sank. Shortly thereafter, Hipper ordered his ships to turn back to German waters. On the way, a heavy fog covered the Heligoland Bight, so the ships were ordered to halt until visibility improved and they could safely navigate the defensive minefields. The armored cruiser Yorck made a navigational error that led her into one of the German minefields. She struck two mines and quickly sank; only 127 men out of the crew of 629 were rescued.[18]

Bombardment of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby

Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, commander of the German High Seas Fleet, decided that another raid on the English coast should be carried out in the hopes of luring a portion of the Grand Fleet into combat where it could be destroyed.[18] At 03:20, CET on 15 December 1914, Blücher, Moltke, Von der Tann, the new battlecruiser Derfflinger, and Seydlitz, along with the light cruisers Kolberg, Strassburg, Stralsund, Graudenz, and two squadrons of torpedo boats left the Jade estuary.[19] The ships sailed north past the island of Heligoland, until they reached the Horns Reef lighthouse, at which point the ships turned west towards Scarborough. Twelve hours after Hipper left the Jade, the High Seas Fleet, consisting of 14 dreadnoughts and eight pre-dreadnoughts and a screening force of two armored cruisers, seven light cruisers, and 54 torpedo boats, departed to provide distant cover for the bombardment force.[19]

On 26 August 1914, the German light cruiser Magdeburg had run aground in the Gulf of Finland; the wreck was captured by the Russian navy, which found code books used by the German navy, along with navigational charts for the North Sea. These documents were then passed on to the Royal Navy. Room 40 began decrypting German signals, and on 14 December, intercepted messages relating to the plan to bombard Scarborough.[19] The exact details of the plan were unknown, and it was assumed that the High Seas Fleet would remain safely in port, as in the previous bombardment. Vice Admiral Beatty's four battlecruisers, supported by the 3rd Cruiser Squadron and the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron, along with the 2nd Battle Squadron's six dreadnoughts, were to ambush Hipper's battlecruisers.[20]

On the night of 15/16 December, the main body of the High Seas Fleet encountered British destroyers. Fearing the prospect of a nighttime torpedo attack, Admiral Ingenohl ordered the ships to retreat.[20] Hipper was unaware of Ingenohl's reversal, and so he continued with the bombardment. Upon reaching the British coast, Hipper's battlecruisers split into two groups. Seydlitz, Moltke, and Blücher went north to shell Hartlepool, while Von der Tann and Derfflinger went south to shell Scarborough and Whitby. Of the three towns, only Hartlepool was defended by coastal artillery batteries.[21] During the bombardment of Hartlepool, Seydlitz was hit three times and Blücher was hit six times by the coastal battery. Blücher suffered minimal damage, but nine men were killed and another three were wounded.[21] By 09:45 on the 16th, the two groups had reassembled, and they began to retreat eastward.[22]

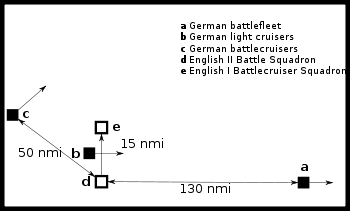

By this time, Beatty's battlecruisers were in position to block Hipper's chosen egress route, while other forces were en route to complete the encirclement. At 12:25, the light cruisers of the II Scouting Group began to pass through the British forces searching for Hipper.[23] One of the cruisers in the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron spotted Stralsund and signaled a report to Beatty. At 12:30, Beatty turned his battlecruisers towards the German ships. Beatty presumed that the German cruisers were the advance screen for Hipper's ships, but the battlecruisers were some 50 km (27 nmi; 31 mi) ahead.[23] The 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, which had been screening for Beatty's ships, detached to pursue the German cruisers, but a misinterpreted signal from the British battlecruisers sent them back to their screening positions.[lower-alpha 5] This confusion allowed the German light cruisers to escape and alerted Hipper to the location of the British battlecruisers. The German battlecruisers wheeled to the northeast of the British forces and made good their escape.[23]

Both the British and the Germans were disappointed that they failed to effectively engage their opponents. Admiral Ingenohl's reputation suffered greatly as a result of his timidity. The captain of Moltke was furious; he stated that Ingenohl had turned back "because he was afraid of eleven British destroyers which could have been eliminated ... Under the present leadership we will accomplish nothing."[24] The official German history criticized Ingenohl for failing to use his light forces to determine the size of the British fleet, stating: "He decided on a measure which not only seriously jeopardized his advance forces off the English coast but also deprived the German Fleet of a signal and certain victory."[24]

Battle of Dogger Bank

In early January 1915 the German naval command found out that British ships were conducting reconnaissance in the Dogger Bank area. Admiral Ingenohl was initially reluctant to attempt to destroy these forces, because the I Scouting Group was temporarily weakened while Von der Tann was in drydock for periodic maintenance. Konteradmiral (counter admiral) Richard Eckermann—the Chief of Staff of the High Seas Fleet—insisted on the operation, and so Ingenohl relented and ordered Hipper to take his battlecruisers to the Dogger Bank.[25]

On 23 January, Hipper sortied, with Seydlitz in the lead, followed by Moltke, Derfflinger, and Blücher, along with the light cruisers Graudenz, Rostock, Stralsund, and Kolberg and 19 torpedo boats from V Flotilla and II and XVIII Half-Flotillas. Graudenz and Stralsund were assigned to the forward screen, while Kolberg and Rostock were assigned to the starboard and port, respectively. Each light cruiser had a half-flotilla of torpedo boats attached.[25]

Again, interception and decryption of German wireless signals played an important role. Although they were unaware of the exact plans, the cryptographers of Room 40 were able to deduce that Hipper would be conducting an operation in the Dogger Bank area.[25] To counter it, Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron, Rear Admiral Gordon Moore's 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron and Commodore William Goodenough's 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron were to rendezvous with Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt's Harwich Force at 08:00 on 24 January, approximately 30 nmi (56 km; 35 mi) north of the Dogger Bank.[25]

At 08:14, Kolberg spotted the light cruiser Aurora and several destroyers from the Harwich Force.[26] Aurora challenged Kolberg with a searchlight, at which point Kolberg attacked Aurora and scored two hits. Aurora returned fire and scored two hits on Kolberg in retaliation. Hipper immediately turned his battlecruisers towards the gunfire, when, almost simultaneously, Stralsund spotted a large amount of smoke to the northwest of her position. This was identified as a number of large British warships steaming toward Hipper's ships.[26] Hipper later remarked:

The presence of such a large force indicated the proximity of further sections of the British Fleet, especially as wireless intercepts revealed the approach of 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron ... They were also reported by Blücher at the rear of the German line, which had opened fire on a light cruiser and several destroyers coming up from astern ... The battlecruisers under my command found themselves, in view of the prevailing [East-North-East] wind, in the windward position and so in an unfavourable situation from the outset ...[26]

Hipper turned south to flee, but was limited to 23 kn (43 km/h; 26 mph), which was Blücher's maximum speed at the time.[lower-alpha 6] The pursuing British battlecruisers were steaming at 27 kn (50 km/h; 31 mph), and quickly caught up to the German ships. At 09:52, Lion opened fire on Blücher from a range of approximately 20,000 yards (18,000 m); shortly after, Princess Royal and Tiger began firing as well.[26] At 10:09, the British guns made their first hit on Blücher. Two minutes later, the German ships began returning fire, primarily concentrating on Lion, from a range of 18,000 yd (16,000 m). At 10:28, Lion was struck on the waterline, which tore a hole in the side of the ship and flooded a coal bunker.[27] At around this time, Blücher scored a hit with a 21 cm shell on Lion's forward turret. The shell failed to penetrate the armor, but had concussion effect and temporarily disabled the left gun.[28] At 10:30, New Zealand—the fourth ship in Beatty's line—came within range of Blücher and opened fire. By 10:35, the range had closed to 17,500 yd (16,000 m), at which point the entire German line was within the effective range of the British ships. Beatty ordered his battlecruisers to engage their German counterparts.[lower-alpha 7]

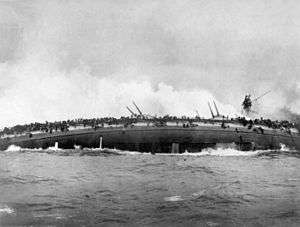

By 11:00, Blücher had been severely damaged after having been pounded by numerous heavy shells from the British battlecruisers. However, the three leading German battlecruisers, Seydlitz, Derfflinger, and Moltke, had concentrated their fire on Lion and scored several hits; two of her three dynamos were disabled and the port side engine room had been flooded.[29] At 11:48, Indomitable arrived on the scene, and was directed by Beatty to destroy the battered Blücher, which was already on fire and listing heavily to port. One of the ship's survivors recounted the destruction that was being wrought:

The shells ... bore their way even to the stokehold. The coal in the bunkers was set on fire. Since the bunkers were half empty, the fire burned merrily. In the engine room a shell licked up the oil and sprayed it around in flames of blue and green ... The terrific air pressure resulting from [an] explosion in a confined space ... roar[ed] through every opening and [tore] its way through every weak spot ... Men were picked up by that terrific air pressure and tossed to a horrible death among the machinery.[29]

The British attack was interrupted due to reports of U-boats ahead of the British ships. Beatty quickly ordered evasive maneuvers, which allowed the German ships to increase the distance from their pursuers.[30] At this time, Lion's last operational dynamo failed, which reduced her speed to 15 kn (28 km/h; 17 mph). Beatty, in the stricken Lion, ordered the remaining battlecruisers to "Engage the enemy's rear", but signal confusion caused the ships to target Blücher alone.[31] She continued to resist stubbornly; Blücher repulsed attacks by the four cruisers of the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron and four destroyers. However, the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron flagship, Aurora, hit Blücher twice with torpedoes. By this time, every main battery gun turret except the rear mount had been silenced. A volley of seven more torpedoes was launched at point-blank range; these hits caused the ship to capsize at 13:13. In the course of the engagement, Blücher had been hit by 70–100 large-caliber shells and several torpedoes.[32]

As the ship was sinking, British destroyers steamed towards her in an attempt to rescue survivors from the water. However, the German zeppelin L5 mistook the sinking Blücher for a British battlecruiser, and tried to bomb the destroyers, which withdrew.[31] Figures vary on the number of casualties; Paul Schmalenbach reported 6 officers of a total of 29 and 275 enlisted men of a complement of 999 were pulled from the water, for a total of 747 men killed.[32] The official German sources examined by Erich Gröner stated that 792 men died when Blücher sank,[9] while James Goldrick referred to British documents, which reported only 234 men survived from a crew of at least 1,200.[33] Among those who had been rescued was Kapitan zur See (captain at sea) Erdmann, the commanding officer of Blücher. He later died of pneumonia while in British captivity.[31] A further twenty men would also die as prisoners of war.[32]

The concentration on Blücher allowed Moltke, Seydlitz, and Derfflinger to escape.[34] Admiral Hipper had originally intended to use his three battlecruisers to turn about and flank the British ships, in order to relieve the battered Blücher, but when he learned of the severe damage to his flagship, he decided to abandon the armored cruiser.[31] Hipper later recounted his decision:

In order to help the Blücher it was decided to try for a flanking move ... But as I was informed that in my flagship turrets C and D were out of action, we were full of water aft, and that she had only 200 rounds of heavy shell left, I dismissed any further thought of supporting the Blücher. Any such course, now that no intervention from our Main Fleet was to be counted on, was likely to lead to further heavy losses. The support of the Blücher by the flanking move would have brought my formation between the British battlecruisers and the battle squadrons which were probably behind.[31]

By the time Beatty regained control over his ships, after having boarded HMS Princess Royal, the German ships had too great a lead for the British to catch them; at 13:50, he broke off the chase.[31] Kaiser Wilhelm II was enraged by the destruction of Blücher and the near sinking of Seydlitz, and ordered the High Seas Fleet to remain in harbor. Rear Admiral Eckermann was removed from his post and Admiral Ingenohl was forced to resign. He was replaced by Admiral Hugo von Pohl.[35]

Footnotes

Notes

- "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (English: His Majesty's Ship).

- German warships were ordered under provisional names. For new additions to the fleet, they were given a single letter; for those ships intended to replace older or lost vessels, they were ordered as "Ersatz (name of the ship to be replaced)".

- Contemporary German naval doctrine called for a scouting group to be made up with at least four large ships, or half a squadron. See Philbin, p. 119, Scheer, p. 13. As the largest non-capital warship in the fleet, Blücher was frequently employed as the fourth.

- In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick firing, while the L/45 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/45 gun is 45 caliber, meaning that the gun's barrel is 45 times as long as the diameter of its bore. See: Grießmer, p. 177.

- Beatty had intended to retain only the two rearmost light cruisers from Goodenough's squadron, but HMS Nottingham's signalman misinterpreted the signal, thinking that it was intended for the whole squadron, and thus transmitted it to Goodenough, who ordered his ships back into their screening positions ahead of Beatty's battlecruisers.

- Throughout the war, the German Navy suffered from a chronic shortage of high-quality coal. Consequently, its ships′ engines could not operate at maximum performance. For example, at the Battle of Jutland, the battlecruiser Von der Tann, which had a maximum speed of 27.5 kn (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph), was limited to 18 kn (33 km/h; 21 mph) for a significant length of time as a result of this problem. See: Philbin, pp. 56–57.

- Thus, Lion on Seydlitz, Tiger on Moltke, Princess Royal on Derfflinger, and New Zealand on Blücher.

Citations

- Rüger, p. 160.

- Staff, p. 3.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 142.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 134.

- Herwig, p. 45.

- Gröner, p. 52.

- Staff, pp. 3, 4.

- Staff, p. 4.

- Gröner, p. 53.

- Friedman, p. 91.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 140.

- Staff, p. 6.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 151.

- Halpern, p. 185.

- Tarrant, p. 30.

- Tarrant, p. 31.

- Tarrant, p. 32.

- Tarrant, p. 33.

- Scheer, p. 70.

- Tarrant, p. 34.

- Tarrant, p. 35.

- Tarrant, p. 36.

- Tarrant, p. 38.

- Tarrant, p. 39.

- Goldrick, p. 263.

- Tarrant, p. 40.

- Tarrant, pp. 40–41.

- Tarrant, p. 42.

- Schmalenbach, p. 180.

- Goldrick, p. 279.

- Tarrant, p. 41.

- Tarrant, p. 43.

References

- Friedman, Norman (1978). Battleship Design and Development, 1905–1945. New York City: Mayflower Books. ISBN 978-0-8317-0700-2.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Goldrick, James (1984). The King's Ships Were at Sea: The War in the North Sea, August 1914 – February 1915. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-334-2. OCLC 10323116.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy: 1906–1918; Constructions between Arms Competition and Fleet Laws] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6. OCLC 22101769.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7. OCLC 57447525.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst, New York: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9. OCLC 57239454.

- Philbin, Tobias R. III (1982). Admiral Hipper: The Inconvenient Hero. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-6032-200-0.

- Rüger, Jan (2007). The Great Naval Game: Britain and Germany in the Age of Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87576-9. OCLC 124025616.

- Schmalenbach, Paul (1971). "SMS Blücher". Warship International. Toledo, Ohio: Naval Records Club. VIII (2): 171–181.

- Scheer, Reinhard (1920). Germany's High Seas Fleet in the World War. London, New York: Cassell. OCLC 2765294. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- Staff, Gary (2006). German Battlecruisers: 1914–1918. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-009-3. OCLC 64555761.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9. OCLC 48131785.

Online sources

- DiGiulian, Tony (29 February 2008). "German 21 cm/45 (8.27") SK L/45". NavWeaps.com. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- DiGiulian, Tony (6 July 2007). "German 15 cm/45 (5.9") SK L/45". NavWeaps.com. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- DiGiulian, Tony (16 April 2009). "German 8.8 cm/45 (3.46") SK L/45, 8.8 cm/45 (3.46") Tbts KL/45, 8.8 cm/45 (3.46") Flak L/45". NavWeaps.com. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

External links