Königsberg-class cruiser (1905)

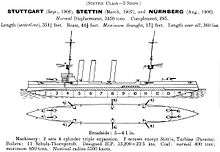

The Königsberg class was a group of four light cruisers built for the German Imperial Navy. The class comprised four vessels: SMS Königsberg, the lead ship, SMS Nürnberg, SMS Stuttgart, and SMS Stettin. The ships were an improvement on the preceding Bremen class, being slightly larger and faster, and mounting the same armament of ten 10.5 cm SK L/40 guns and two 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes.

SMS Königsberg | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | Bremen class |

| Succeeded by: | Dresden class |

| Built: | 1905–07 |

| In service: | 1907–18 |

| Completed: | 4 |

| Lost: | 2 |

| Retired: | 2 |

| General characteristics [lower-alpha 1] | |

| Type: | Light cruiser |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 115.30 m (378 ft 3 in) |

| Beam: | 13.20 m (43 ft 4 in) |

| Draft: | 5.29 m (17 ft 4 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 23 knots (42.6 km/h) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

The four ships saw extensive service during World War I. Königsberg conducted commerce warfare in the Indian Ocean before being trapped in the Rufiji River and sunk by British warships. Her guns nevertheless continued to see action as converted artillery pieces for the German Army in German East Africa. Nürnberg was part of the German East Asia Squadron, and participated in the Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands. At the former, she sank the British armored cruiser HMS Monmouth, and at the latter, she was in turn sunk by the cruiser HMS Kent.

Stuttgart and Stettin remained in German waters during the war, and both saw action at the Battle of Jutland on 31 May and 1 June 1916. The two cruisers engaged in close-range night fighting with the British fleet, but neither was significantly damaged. Both ships were withdrawn from service later in the war, Stettin to serve as a training ship, and Stuttgart to be converted into a seaplane tender in 1918. They both survived the war, and were surrendered to Britain as war prizes; they were dismantled in the early 1920s.

Design

The 1898 Naval Law authorized the construction of 30 new light cruisers by 1904;[1] the Gazelle and Bremen classes filled the requirements for the first seventeen vessels. The Königsberg design followed the same general parameters as the two earlier classes, but with significant improvements in terms of size and speed. Like the Bremens, one member of the Königsberg class, Stettin, was fitted with steam turbines to evaluate their performance compared to traditional triple-expansion engines.[2][3]

General characteristics

The ships of the Königsberg class had slightly different characteristics. The lead ship was 114.80 meters (376 ft 8 in) long at the waterline and 115.30 m (378 ft 3 in) long overall. She had a beam of 13.2 m (43 ft 4 in) and a draft of 5.29 m (17 ft 4 in) forward. The remaining three ships were 116.80 m (383 ft 2 in) long at the waterline and 117.40 m (385 ft 2 in) long overall; they had a beam of 13.3 m (43 ft 8 in) and a draft of 5.14 to 5.4 m (16 ft 10 in to 17 ft 9 in) forward. Königsberg displaced 3,390 metric tons (3,340 long tons) as designed and up to 3,814 t (3,754 long tons) at full load. Nürnberg and Stuttgart were designed to displace 3,469 t (3,414 long tons), with full load displacements of 3,902 t (3,840 long tons) and 4,002 t (3,939 long tons), respectively. Stettin displaced 3,480 t (3,430 long tons) as designed and 3,822 t (3,762 long tons) at combat load.[4]

The ships' hulls were constructed with transverse and longitudinal steel frames, over which the steel outer hull was built. The hulls were divided into thirteen or fourteen watertight compartments. A double bottom ran for forty-seven percent of the length of the keel. Steering was controlled by a single rudder. The ships of the class were good sea boats, but they were crank and rolled up to twenty degrees. They were also very wet at high speeds and suffered from a slight weather helm; in the case of Stuttgart, she suffered from quite severe weather helm. The ships' metacentric height was .54 to .65 m (1 ft 9 in to 2 ft 2 in). The ships had a crew of fourteen officers and 308 enlisted men. They carried a number of smaller boats, including one picket boat, one barge, one cutter, two yawls, and two dinghies.[4]

Machinery

The first three Königsberg-class ships' propulsion system consisted of two 3-cylinder triple expansion engines rated at 13,200 indicated horsepower (9,800 kW) for a top speed of 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph). Stettin was instead equipped with a pair of Parsons steam turbines, rated at 13,500 shaft horsepower (10,100 kW) and a top speed of 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph). Each ship exceeded their design speed by at least half a knot on speed trials, however. All four ships' engines were powered by eleven coal-fired Marine-type boilers, which were trunked into three funnels. The ships were designed to carry 400 t (390 long tons) of coal, though they could store up to 880 t (870 long tons). Königsberg could steam for 5,750 nautical miles (10,650 km; 6,620 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph), while the other three ships' ranges were considerably shorter. Nürnberg and Stuttgart could cruise for 4,120 nmi (7,630 km; 4,740 mi) at the same speed, and Stettin had a range of 4,170 nmi (7,720 km; 4,800 mi). Königsberg had two electricity generators, while the other three ships were equipped with three generators. The generators produced a total output of 90 and 135 kilowatts at 100 volts, respectively.[4]

Armament and armor

The ships were armed with ten 10.5 cm SK L/40 guns in single pedestal mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, six were located amidships, three on either side, and two were side by side aft.[2] The guns had a maximum elevation of 30 degrees, which allowed them to engage targets out to 12,700 m (13,900 yd).[5] They were supplied with 1,500 rounds of ammunition, for 150 shells per gun.[4] Königsberg later had a pair of 8.8 cm (3.5 in) guns installed.[6] The last three ships were also equipped with eight 5.2 cm SK L/55 guns with 4,000 rounds of ammunition. All four ships were also equipped with a pair of 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes with five torpedoes submerged in the hull on the broadside.[4]

Armor protection for the members of the class consisted of two layers of steel with one layer of Krupp armor. The ships of the Königsberg class were protected by an armored deck that was 80 millimeters (3.1 in) thick amidships, and reduced to 20 mm (0.79 in) thick aft. Sloped armor 45 mm (1.8 in) thick gave a measure of vertical protection. The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick sides and a 20 mm thick roof. The ships' guns were protected with 50 mm (2.0 in) thick gun shields.[4]

Construction

The first three ships of the class were built by government shipyards. Königsberg was laid down at the Imperial Dockyard in Kiel in 1905, launched on 12 December 1905, and commissioned into the German Navy on 6 April 1907. Nürnberg was also laid down at the Imperial Dockyard in Kiel, in 1906. Her launching occurred on 28 August 1906, and she was commissioned on 10 April 1908. Stuttgart was built by the Imperial Dockyard in Danzig. She was laid down in 1905, launched on 22 September 1906, and commissioned on 1 February 1908. Stettin was the only ship of the class built by a private shipbuilding firm, by AG Vulcan in her namesake city. She was laid down in 1906, launched on 7 March 1907, and commissioned just seven months later on 29 October 1907.[7]

Service history

The ships of the Königsberg class served with the High Seas Fleet after their commissionings, though Stuttgart also saw service as a gunnery training ship. Nürnberg and Königsberg were deployed overseas in 1910 and 1914, respectively.[7] Nürnberg was sent to the East Asia Squadron,[8] while Königsberg went to east African waters.[9] Stuttgart and Stettin meanwhile remained in Germany.[10]

All four ships had active careers during World War I and saw action at many major battles during the conflict. At the outbreak of war, Königsberg was stationed in German East Africa; she was ordered to begin raiding British commerce in the region.[11] She was relatively unsuccessful in this regard, having sunk only the British freighter City of Winchester.[12] She did, however, surprise the British cruiser HMS Pegasus in harbor and sank her in the Battle of Zanzibar.[13] She was then blockaded in the Rufiji River and eventually destroyed by two British monitors, HMS Mersey and HMS Severn.[14] Königsberg's guns were removed from the wreck and mounted on improvised gun carriages and used in German East Africa during the World War I land campaign.[15]

Nürnberg was still assigned to the East Asia Squadron under Admiral Maximilian von Spee when war broke out. Initially based in Tsingtao, China, the squadron crossed the Pacific in an attempt to raid British commerce off South America.[16] The ship saw action at the Battle of Coronel in November 1914 where a British squadron attempted to intercept the German flotilla. There she sank the British armored cruiser HMS Monmouth.[17] The following month during the Battle of the Falkland Islands, Nürnberg was sunk by the armored cruiser HMS Kent, part of another British squadron sent to hunt down Spee's squadron.[18]

Stettin and Stuttgart both saw action with the High Seas Fleet in the North Sea. Stettin participated in the Battle of Heligoland Bight in August 1914, and suffered relatively minor damage.[19] Both cruisers participated in the Battle of Jutland on 31 May and 1 June 1916.[20] Stettin was hit twice but was not badly damaged during the night,[21] while Stuttgart emerged from the battle unscathed.[22] Both ships were withdrawn from service in 1917; Stettin was used as a training ship, while Stuttgart was converted into a seaplane tender in 1918. The two ships survived the war and were surrendered to Britain as war prizes; they were later broken up for scrap in the early 1920s.[10]

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Königsberg class cruiser (1905). |

Footnotes

- Figures varied across the class; these statistics are those of the lead ship, SMS Königsberg.

Citations

- Herwig, p. 42

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 157

- Herwig, pp. 45–46

- Gröner, p. 104

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 140

- Farwell, p. 127

- Gröner, pp. 104–105

- Gray, p. 184

- Farwell, p. 128

- Gröner, p. 105

- Halpern, p. 77

- Hoyt, p. 40

- Farwell, p. 133

- Bennett, pp. 132–134

- Herwig, pp. 154–155

- Halpern, pp. 71–72

- Bennett, p. 94

- Bennett, p. 125

- Staff, pp. 7–11

- Tarrant, p. 62

- Campbell, pp. 280–281, 390

- Tarrant, p. 296

References

- Bennett, Geoffrey (2005). Naval Battles of the First World War. London: Pen & Sword Military Classics. ISBN 1-84415-300-2.

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 1-55821-759-2.

- Farwell, Byron (1989). The Great War in Africa, 1914–1918. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-30564-3.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Gray, J.A.C. (1960). Amerika Samoa, A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-790-9.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Herwig, Holger (1980). "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hoyt, Edwin P. (1969). The Germans Who Never Lost. London: Frewin. ISBN 0-09-096400-4.

- Nottleman, Dirk (2020). "The Development of the Small Cruiser in the Imperial German Navy (Part I)". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2020. Oxford: Osprey. pp. 102–118. ISBN 978-1-4728-4071-4.

- Staff, Gary (2011). Battle on the Seven Seas. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84884-182-6.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 0-304-35848-7.

Further reading

- Koop, Gerhard; Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (2004). Kleine Kreuzer 1903–1918: Bremen bis Cöln-Klasse [Small Cruisers 1903–1918: The Bremen Through Cöln Classes] (in German). München: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 3-7637-6252-3.