Displacement (ship)

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into weight. Traditionally, various measurement rules have been in use, giving various measures in long tons.[1] Today, metric tonnes are more commonly used.

.jpg)

Ship displacement varies by a vessel's degree of load, from its empty weight as designed (known as "lightweight tonnage"[2]) to its maximum load. Numerous specific terms are used to describe varying levels of load and trim, detailed below.

Ship displacement should not be confused with measurements of volume or capacity typically used for commercial vessels and measured by tonnage: net tonnage, gross tonnage, and deadweight tonnage.

Calculation

The process of determining a vessel's displacement begins with measuring its draft[3] This is accomplished by means of its "draft marks" (or "load lines"). A merchant vessel has three matching sets: one mark each on the port and starboard sides forward, midships, and astern.[3] These marks allow a ship's displacement to be determined to an accuracy of 0.5%.[3]

The draft observed at each set of marks is averaged to find a mean draft. The ship's hydrostatic tables show the corresponding volume displaced.[4] To calculate the weight of the displaced water, it is necessary to know its density. Seawater (1025 kg/m3) is more dense than fresh water (1000 kg/m3);[5] so a ship will ride higher in salt water than in fresh. The density of water also varies with temperature.

Devices akin to slide rules have been available since the 1950s to aid in these calculations. It is done today with computers.[6]

Displacement is usually measured in units of tonnes or long tons.[7]

Definitions

There are terms for the displacement of a vessel under specified conditions:

Loaded displacement

- Loaded displacement is the weight of the ship including cargo, passengers, fuel, water, stores, dunnage and such other items necessary for use on a voyage. These bring the ship down to its "load draft",[8] colloquially known as the "waterline".

- Full load displacement and loaded displacement have almost identical definitions. Full load is defined as the displacement of a vessel when floating at its greatest allowable draft as established by a classification society (and designated by its "waterline").[9] Warships have arbitrary full load condition established.[9]

- Deep load condition means full ammunition and stores, with most available fuel capacity used.

Light displacement

- Light displacement (LDT) is defined as the weight of the ship excluding cargo, fuel, water, ballast, stores, passengers, crew, but with water in boilers to steaming level.[8]

Normal displacement

- Normal displacement is the ship's displacement "with all outfit, and two-thirds supply of stores, ammunition, etc., on board."[10]

Standard displacement

- Standard displacement, also known as "Washington displacement", is a specific term defined by the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922.[11] It is the displacement of the ship complete, fully manned, engined, and equipped ready for sea, including all armament and ammunition, equipment, outfit, provisions and fresh water for crew, miscellaneous stores, and implements of every description that are intended to be carried in war, but without fuel or reserve boiler feed water on board.[11]

Gallery

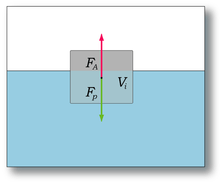

A floating ship's displacement Fp and buoyancy Fa must be equal

A floating ship's displacement Fp and buoyancy Fa must be equal Greek philosopher Archimedes having his famous bath, the birth of the theory of displacement

Greek philosopher Archimedes having his famous bath, the birth of the theory of displacement- A ship's hydrostatic curves. Lines 4 and 5 are used to convert from mean draft in meters to displacement in tonnes (table in Spanish)

See also

- Naval architecture

- Hull (watercraft)

- Hydrodynamics

- Tonnage

References

- "Ship Tonnage Explained - Displacement, Deadweight, Etc. | GG Archives". www.gjenvick.com. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- "A Guide to Understanding Ship Weight and Tonnage Measurements – The Maritime Site". www.themaritimesite.com. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- George, 2005. p.5.

- George, 2005. p. 465.

- Turpin and McEwen, 1980.

- George, 2005. p. 262.

- Otmar Schäuffelen (2005). Chapman Great Sailing Ships of the World. Hearst Books. p. xix.

- Military Sealift Command.

- Department of the Navy, 1942.

- United States Naval Institute, 1897. p 809.

- Conference on the Limitation of Armament, 1922. Ch II, Part 4.

Bibliography

- Dear, I.C.B.; Kemp, Peter (2006). Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea (Paperback ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-920568-X.

- George, William E. (2005). Stability & Trim for the Ship's Officer. Centreville, Md: Cornell Maritime Press. ISBN 0-87033-564-2.

- Hayler, William B. (2003). American Merchant Seaman's Manual. Cambridge, Md: Cornell Maritime Press. ISBN 0-87033-549-9..

- Turpin, Edward A.; McEwen, William A. (1980). Merchant Marine Officers' Handbook (4th ed.). Centreville, MD: Cornell Maritime Press. ISBN 0-87033-056-X.

- Navy Department (1942). "Nomenclature of Naval Vessels". history.navy.mil. United States Navy. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- Military Sealift Command. "Definitions, Tonnages and Equivalents". MSC Ship Inventory. United States Navy. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- MLCPAC Naval Engineering Division (2005-11-01). "Trim and Stability Information for Drydocking Calculations". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- United States of America (1922). "Conference on the Limitation of Armament, 1922". Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States: 1922. 1. pp. 247–266.

- United States Naval Institute (1897). Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. United States Naval Institute. Retrieved 2008-03-24.