SMS Stralsund

SMS Stralsund was a Magdeburg-class light cruiser of the German Kaiserliche Marine. Her class included three other ships: Magdeburg, Breslau, and Strassburg. She was built at the AG Weser shipyard in Bremen from 1910 to December 1912, when she was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet. The ship was armed with a main battery of twelve 10.5 cm SK L/45 guns and had a top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph).

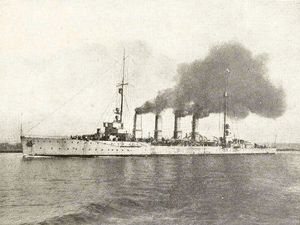

Stralsund in French service as Mulhouse | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Stralsund |

| Namesake: | Stralsund |

| Builder: | AG Weser, Bremen |

| Laid down: | 1910 |

| Launched: | 4 November 1911 |

| Commissioned: | 10 December 1912 |

| Fate: | Ceded to France in 1920 and scrapped in 1935 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Magdeburg-class cruiser |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 138.7 m (455 ft 1 in) |

| Beam: | 13.5 m (44 ft 3 in) |

| Draft: | 4.4 m (14 ft 5 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph) |

| Range: | 5,820 nmi (10,780 km; 6,700 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Stralsund was assigned to the reconnaissance forces of the High Seas Fleet for the majority of her career. She saw significant action in the early years of World War I, including several operations off the British coast and the Battles of Heligoland Bight and Dogger Bank, in August 1914 and November 1915, respectively. She was not damaged in either action. The ship was in dockyard hands during the Battle of Jutland, and so she missed the engagement. After the end of the war, she served briefly in the Reichsmarine before being surrendered to the Allies. She was ceded to the French Navy, where she served as Mulhouse until 1925. She was formally stricken in 1933 and broken up for scrap two years later.

Design

Stralsund was 138.7 meters (455 ft) long overall and had a beam of 13.5 m (44 ft) and a draft of 4.4 m (14 ft) forward. She displaced 4,570 t (4,500 long tons; 5,040 short tons) normally and up to 5,587 t (5,499 long tons) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of two sets of AEG-Vulcan steam turbines driving two 3.4-meter (11 ft) propellers. They were designed to give 25,000 shaft horsepower (19,000 kW), but reached 33,482 shp (24,968 kW) in service. These were powered by sixteen coal-fired Marine-type water-tube boilers, although they were later altered to use fuel oil that was sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate. These gave the ship a top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph). Stralsund carried 1,200 t (1,200 long tons) of coal, and an additional 106 t (104 long tons) of oil that gave her a range of approximately 5,820 nautical miles (10,780 km; 6,700 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Stralsund had a crew of 18 officers and 336 enlisted men.[1]

The ship was armed with a main battery of twelve 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/45 guns in single pedestal mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, eight were located amidships, four on either side, and two were side by side aft. The guns had a maximum elevation of 30 degrees, which allowed them to engage targets out to 12,700 m (41,700 ft).[2] They were supplied with 1,800 rounds of ammunition, for 150 shells per gun. She was also equipped with a pair of 50 cm (19.7 in) torpedo tubes with five torpedoes; the tubes were submerged in the hull on the broadside. She could also carry 120 mines. The ship was protected by a waterline armored belt that was 60 mm (2.4 in) thick amidships. The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick sides, and the deck was covered with up to 60 mm thick armor plate.[3]

Service history

Stralsund was ordered under the contract name "Ersatz Cormoran" and was laid down at the AG Weser shipyard in Bremen in 1910 and launched on 4 November 1911, after which fitting-out work commenced. She was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet on 10 December 1912.[1] Stralsund spent the majority of her career in the reconnaissance forces of the High Seas Fleet.[4] On 16 August, some two weeks after the outbreak of World War I, Stralsund and Strassburg conducted a sweep into the Hoofden to search for British reconnaissance forces. The two cruisers encountered a group of sixteen British destroyers and a light cruiser at a distance of about 10,000 m (33,000 ft). Significantly outnumbered, the two German cruisers broke contact and returned to port.[5]

The ship's first major action was the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28 August 1914. British battlecruisers and light cruisers raided the German reconnaissance screen in the Heligoland Bight. At 12:30, Stralsund, Danzig, and Ariadne arrived to reinforce Rear Admiral Leberecht Maass, and quickly turned the tide against the British light cruisers. Shortly thereafter, the British battlecruisers intervened and sank Ariadne and Maass's flagship Cöln. Stralsund and the rest of the surviving light cruisers retreated into the haze and were reinforced by the battlecruisers of the I Scouting Group.[6] Stralsund and Danzig returned and rescued most of the crew of Ariadne.[7]

She also participated in the raid on Yarmouth on 2–3 November 1914, as reconnaissance screen for the I Scouting Group. While the battlecruisers bombarded the town of Yarmouth, Stralsund laid a minefield, which sank a steamer and the submarine HMS D5 which had sortied to intercept the German raiders. After completing the bombardment, the German squadron returned to port without encountering British forces. Stralsund was also present during the raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, again screening for the I Scouting Group. In the withdrawal after bombarding the towns, the Germans were nearly intercepted by British forces; the cruiser HMS Southampton spotted Stralsund and several torpedo boats. Confusion aboard the British flagship allowed the German squadron to escape, however.[8] On 25 December, the British launched the Cuxhaven Raid, an air attack on the German naval base in Cuxhaven and the Nordholz Airbase. Stralsund engaged one of the attacking seaplanes, but was unable to shoot it down.[9]

The ship was again part of the reconnaissance screen for the I Scouting Group at the Battle of Dogger Bank on 24 January 1915. Stralsund and Graudenz were assigned to the front of the screen and Rostock and Kolberg steamed on either side of the formation; each cruiser was supported by a half-flotilla of torpedo boats. At 08:15, lookouts on Stralsund and Kolberg spotted heavy smoke from large British warships approaching the formation. As the main German fleet was in port and therefore unable to support the battlecruisers, Hipper decided to retreat at high speed. The British battlecruisers were able to catch up to the Germans, however, and in the ensuing battle, the large armored cruiser Blücher was sunk.[10]

Stralsund was not available for the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916 as she was being rearmed with 15 cm SK L/45 guns.[11] The refit was completed at the Kaiserliche Werft shipyard in Kiel. The twelve 10.5 cm guns were replaced with seven 15 cm weapons and two 8.8 cm SK L/45 guns.[1] On 2 February 1918, Stralsund struck a mine laid by British ships in the North Sea. The dreadnought Kaiser and several other ships steamed out to escort Stralsund back to port.[12] The ship was unavailable for the major fleet operation on 23–24 April 1918 to intercept a British convoy to Norway.[13]

Postwar and French service

After the war, Stralsund served briefly with the reorganized Reichsmarine in 1919.[14] The Treaty of Versailles specified that the ship was to be disarmed and handed over to the Allies within two months of the signing of the treaty.[15] She was ceded to France as a war prize under the transaction name "Z". The ship was formally handed over in Cherbourg on 3 August 1920.[14] On arriving in France, she underwent a minor refit that consisted primarily of replacing her 8.8 cm guns with 75 mm (3.0 in) anti-aircraft guns.[16]

The ship was renamed Mulhouse and served briefly with the French Navy in the French Mediterranean Fleet as part of the 3rd Light Division in company with the other ex-German cruisers Metz and Strasbourg and the ex-Austro-Hungarian Thionville.[16] Mulhouse remained in service until a refit in 1925 in Brest. By this time, she was thoroughly worn out and was therefore placed in reserve shortly after completing the refit. On 15 February 1933, Mulhouse was stricken from the naval register and broken up for scrap in Brest in 1935. The ship's bell was later returned to Germany and is now on display at the Laboe Naval Memorial.[14][17]

Footnotes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stralsund (ship, 1911). |

- Gröner, pp. 107–108.

- Gardiner & Gray, pp. 140, 159.

- Gröner, p. 107.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 160.

- Scheer, p. 42.

- Bennett, pp. 145–150.

- Scheer, p. 45.

- Tarrant, pp. 30–34.

- Barber, p. 48.

- Scheer, pp. 77–85.

- Campbell, p. 23.

- Staff, p. 12.

- Halpern, p. 418.

- Gröner, p. 108.

- See: Treaty of Versailles Section II: Naval Clauses, Article 185

- Dodson, p. 151.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 201.

References

- Barber, Mark (2010). Royal Naval Air Service Pilot 1914–18. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-949-2.

- Bennett, Geoffrey (2005). Naval Battles of the First World War. London: Pen & Sword Military Classics. ISBN 1-84415-300-2.

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 1-55821-759-2.

- Dodson, Aidan (2017). "After the Kaiser: The Imperial German Navy's Light Cruisers after 1918". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2017. London: Conway. pp. 140–159. ISBN 978-1-8448-6472-0.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Scheer, Reinhard (1920). Germany's High Seas Fleet in the World War. London: Cassell and Company. OCLC 52608141.

- Staff, Gary (2006). German Battlecruisers: 1914–1918. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-009-3.

- Tarrant, V.E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.