Platelet-activating factor

Platelet-activating factor, also known as PAF, PAF-acether or AGEPC (acetyl-glyceryl-ether-phosphorylcholine), is a potent phospholipid activator and mediator of many leukocyte functions, platelet aggregation and degranulation, inflammation, and anaphylaxis. It is also involved in changes to vascular permeability, the oxidative burst, chemotaxis of leukocytes, as well as augmentation of arachidonic acid metabolism in phagocytes.

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| MeSH | Platelet+Activating+Factor |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C26H54NO7P | |

| Molar mass | 523.683 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

PAF is produced by a variety of cells, but especially those involved in host defense, such as platelets, endothelial cells, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages. PAF is continuously produced by these cells but in low quantities and production is controlled by the activity of PAF acetylhydrolases. It is produced in larger quantities by inflammatory cells in response to specific stimuli.[1]

History

PAF was discovered by French immunologist Jacques Benveniste in the early 1970s.[2][3] PAF was the first phospholipid known to have messenger functions. Benveniste made significant contributions in the role and characteristics of PAF and its importance in inflammatory response and mediation. Using lab rats and mice, he found that ionophore A23187 (a mobile ion carrier that allows the passage of Mn2+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ and has antibiotic properties against bacteria and fungi) caused the release of PAF. These developments led to the finding that macrophages produce PAF and that macrophages play an important function in aggregation of platelets and liberation of their inflammatory and vasoactive substances.

Further studies on PAF were conducted by Constantinos A. Demopoulos in 1979.[4] Demopoulos found that PAF plays a crucial role in heart disease and strokes. His experiment’s data found that atherosclerosis (the accumulation of lipid-rich lesions in the endothelium of the arteries) can be attributed to PAF and PAF-like lipids, and identified biologically active compounds in the polar lipid fractions of olive oil, honey, milk and yoghurt, mackerel, and wine that have PAF-antagonistic properties and inhibit the development of atherosclerosis in animal models.[5] During the course of his studies, he also determined the chemical structure of the compound.

Evolution

PAF can be found in protozoans, yeasts, plants, bacteria, and mammals. PAF has regulatory role in protozoans. The regulatory role is thought to diverge from that point and be maintained as living organisms started to evolve. During evolution, functions of PAF in the cell have been changing and enlarging.

PAF has been found in plants but its function has not yet been determined.

Fungal PAF

The antifungal protein PAF from Penicillium chrysogenum exhibits growth-inhibitory activity against a broad range of filamentous fungi. Evidence suggests that disruption of Ca2+ signaling/homeostasis plays an important role in the mechanistic basis of PAF as a growth inhibitor.[6]

PAF also elicits hyperpolarization of the plasma membrane and the activation of ion channels, followed by an increase in reactive oxygen species in the cell and the induction of an apoptosis-like phenotype [7]

Cumulative evidence reveals that diabetes is a condition in which cell Ca2+ homeostasis is impaired. Defects in cell Ca2+ regulation were found in erythrocytes, cardiac muscle, platelets, skeletal muscle, kidney, aorta, adipocytes, liver, osteoblasts, arteries, lens, peripheral nerves, brain synaptosomes, retinal tissue, and pancreatic beta cells, confirming that this defect in cell Ca2+ metabolism is a basic pathology associated with the diabetic state.[8]

The defects identified in the mechanical activity of the hearts from type 1 diabetic animals include alteration of Ca2+ signaling via changes in critical processes.[9]

Function

PAF is used to transmit signals between neighboring cells and acts as a hormone, cytokines, and other signaling molecules. The PAF signaling system can trigger inflammatory and thrombotic cascades, amplify these cascades when acting with other mediators, and mediate molecular and cellular interactions (cross talk) between inflammation and thrombosis.[10] Unregulated PAF signaling can cause pathological inflammation and has been found to be a cause in sepsis, shock, and traumatic injury. PAF can be used as a local signaling molecule and travel over very short distances or it can be circulated throughout the body and act via endocrine.

PAF initiates an inflammatory response in allergic reactions.[11] This has been demonstrated in the skin of humans and in the paws and skin of lab rabbits and rodents. The inflammatory response is enhanced by the use of vasodilators, including prostaglandin E1 (PGE,) and PGE2 and inhibited by vasoconstrictors.[12]

PAF also induces apoptosis in a different way that is independent of the PAF receptor. The pathway to apoptosis can be inhibited by negative feedback from PAF acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH), an enzyme that catabolizes platelet-activating factor.

It is an important mediator of bronchoconstriction.

It causes platelets to aggregate and blood vessels to dilate. Thus, it is important to the process of hemostasis. At a concentration of 10−12 mol/L, PAF causes life-threatening inflammation of the airways to induce asthma like symptoms.

Toxins such as fragments of destroyed bacteria induce the synthesis of PAF, which causes a drop in blood pressure and reduced volume of blood pumped by the heart, which leads to shock and possibly death.

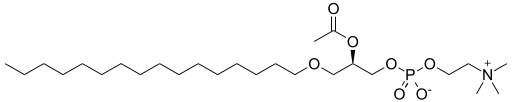

Structure

Several molecular species of platelet-activating factor that vary in the length of the O-alkyl side-chain have been identified.

- Its alkyl group is connected by an ether linkage at the C1 carbon to a 16-carbon chain.

- The acyl group at the C2 carbon is an acetate unit (as opposed to a fatty acid) whose short length increases the solubility of PAF allowing it to function as a soluble signal messenger.

- The C3 has a phosphocholine head group, just like standard phosphatidylcholine.

Studies found that PAF could not be modified without losing its biological activity. Thus, small changes in the structure of PAF could render its signaling abilities inert.[13] Investigation led to the understanding that platelet and blood pressure response were dependent on the sn-2 propionyl analog. If the sn-1 was removed then PAF lacked any sort of biological activity. Finally, the sn-3 position of PAF was experimented with by removing methyl groups sequentially. As more and more methyl groups were removed, biological activity diminished until it was eventually inactive.

Biochemistry

Biosynthesis

PAF is produced by stimulated basophils, monocytes, polymorphonuclear neutrophils, platelets, and endothelial cells primarily through lipid remodeling. A variety of stimuli can initiate the synthesis of PAF. These stimuli could be macrophages going through phagocytosis or endothelium cells uptake of thrombin.

There are two different pathways in which PAF can be synthesized: de novo pathway and remodeling. The remodeling pathway is activated by inflammatory agents and it is thought to be the primary source of PAF under pathological conditions. The de novo pathway is used to maintain PAF levels during normal cellular function.

The most common pathway taken to produce PAF is remodeling. The precursor to the remodeling pathway is a phospholipid, which is typically phosphatidylcholine (PC). The fatty acid is removed from the sn-2 position of the three-carbon backbone of the phospholipid by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) to produce the intermediate lyso-PC (LPC). An acetyl group is then added by LPC acetyltransferase (LPCAT) to produce PAF.

Using the de novo pathway, PAF is produced from 1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (AAG). Fatty acids are joined on the sn-1 position with 1-O-hexadecyl being the best for PAF activity. Phosphocholine is then added to the sn-3 site on AAG creating PAF.

Regulation

The concentration of PAF is controlled by the synthesis of the compound and by the actions of PAF acetylhydrolases (PAF-AH). PAF-AH are a family of enzymes that have the ability to catabolize and degrade PAF and turn it into an inactive compound. The enzymes within this family are lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, cytoplasmic platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase 2, and platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase 1b.

Cations are one form of regulation in the production of PAF. Calcium plays a large role in the inhibition of enzymes that produce PAF in the denovo pathway of PAF biosynthesis.

The regulation of PAF is still not completely understood. Enzymes that are associated with the production of PAF are controlled by metal ions, thiol compounds, fatty acids, pH, compartmentalization, and phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. These controls on these PAF producing enzymes are believed to work in conjunction to control it, but the overall pathway and reasoning is not well understood.

Pharmacology

Inhibition

PAF antagonists is a type of receptor ligand or drug that does not provoke an inflammatory response upon binding, but blocks or lessens the effect of PAF. Examples of PAF antagonists are:[14]

- CV-3988 is a PAF antagonist that blocks signaling events correlated to the expression and binding of PAF to the PAF Receptor.

- SM-12502 is a PAF antagonist, which is metabolized in the liver by the enzyme CYP2A6.[15]

- Rupatadine is an antihistamine and PAF antagonist used to treat allergies.

- Etizolam is a benzodiazepine analog and PAF antagonist used to treat anxiety and panic attacks.[16]

- Apafant[17]

- Lexipafant (Zacutex) for treatment of pancreatitis.

- Modipafant

- A full list in a review: Negro Alvarez JM, Miralles López JC, Ortiz Martínez JL, Abellán Alemán A, Rubio , del Barrio R (1997). "Platelet-activating factor antagonists". Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 25: 249–58. PMID 9395010.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Clinical significance

High PAF levels are associated with a variety of medical conditions. Some of these conditions include:

•Allergic reactions

•Stroke

•Sepsis

•Myocardial infarction

•Colitis, inflammation of the large intestine

•Multiple sclerosis

While the effects that PAF has on inflammatory response and cardiovascular conditions are well understood, PAF is still a subject for discussion. Over the past 23 years, papers written on PAF have almost doubled from approximately 7,500 in 1997 to 14,500 in 2020.PubMed (June 2020). "Platelet-activating factor search results and historical activity metrics". PubMed. Research into PAF is ongoing.

Anti-PAF drugs

Anti-PAF drugs are currently being used in cardiac rehabilitation trials. Anti-PAF drugs are used to block angiotensin II type 1 receptors to lower in the risk of atrial fibrillation in individuals with paroxysmal fibrillation. It is also used to lessen the effects of allergies.

References

- Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Stafforini DM (May 2002). "The platelet-activating factor signaling system and its regulators in syndromes of inflammation and thrombosis". Critical Care Medicine. 30 (5 Suppl): S294–301. doi:10.1097/00003246-200205001-00020. PMID 12004251.

- Benveniste J, Henson PM, Cochrane CG (Dec 1972). "Leukocyte-dependent histamine release from rabbit platelets. The role of IgE, basophils, and a platelet-activating factor". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 136 (6): 1356–77. doi:10.1084/jem.136.6.1356. PMC 2139324. PMID 4118412.

- Benveniste J (Jun 1974). "Platelet-activating factor, a new mediator of anaphylaxis and immune complex deposition from rabbit and human basophils". Nature. 249 (457): 581–2. Bibcode:1974Natur.249..581B. doi:10.1038/249581a0. PMID 4275800.

- Demopoulos CA, Pinckard RN, Hanahan DJ (Oct 1979). "Platelet-activating factor. Evidence for 1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glyceryl-3-phosphorylcholine as the active component (a new class of lipid chemical mediators)" (PDF). The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 254 (19): 9355–8. PMID 489536.

- Lordan R, Tsoupras A, Zabetakis I, Demopoulos CA (December 3, 2019). "Forty Years Since the Structural Elucidation of Platelet-Activating Factor (PAF): Historical, Current, and Future Research Perspectives". Molecules. 24 (23): 4414. doi:10.3390/molecules24234414. PMC 6930554. PMID 31816871. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- Binder U, Chu M, Read ND, Marx F (Sep 2010). "The antifungal activity of the Penicillium chrysogenum protein PAF disrupts calcium homeostasis in Neurospora crassa". Eukaryotic Cell. 9 (9): 1374–82. doi:10.1128/EC.00050-10. PMC 2937333. PMID 20622001.

- Marx F, Binder U, Leiter E, Pócsi I (Feb 2008). "The Penicillium chrysogenum antifungal protein PAF, a promising tool for the development of new antifungal therapies and fungal cell biology studies". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 65 (3): 445–54. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7364-8. PMID 17965829.

- Levy J (Feb 1999). "Abnormal cell calcium homeostasis in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a new look on old disease". Endocrine. 10 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1385/ENDO:10:1:1. PMID 10403564.

- Yaras N, Ugur M, Ozdemir S, Gurdal H, Purali N, Lacampagne A, Vassort G, Turan B (Nov 2005). "Effects of diabetes on ryanodine receptor Ca release channel (RyR2) and Ca2+ homeostasis in rat heart". Diabetes. 54 (11): 3082–8. doi:10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3082. PMID 16249429.

- Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, Stafforini DM, McIntyre TM (2000). "Platelet-activating factor and related lipid mediators". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 69: 419–45. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.419. PMID 10966465.

- McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Stafforini DM (Apr 2009). "The emerging roles of PAF acetylhydrolase". Journal of Lipid Research. 50 Suppl: S255–9. doi:10.1194/jlr.R800024-JLR200. PMC 2674695. PMID 18838739.

- Morley J, Page CP, Paul W (Nov 1983). "Inflammatory actions of platelet activating factor (Pafacether) in guinea-pig skin". British Journal of Pharmacology. 80 (3): 503–9. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1983.tb10722.x. PMC 2045011. PMID 6685552.

- Snyder F (Feb 1989). "Biochemistry of platelet-activating factor: a unique class of biologically active phospholipids". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 190 (2): 125–35. doi:10.3181/00379727-190-42839. PMID 2536942.

- Camussi G, Tetta C, Bussolino F, Baglioni C (Oct 1988). "Synthesis and release of platelet-activating factor is inhibited by plasma alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor or alpha 1-antichymotrypsin and is stimulated by proteinases". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 168 (4): 1293–306. doi:10.1084/jem.168.4.1293. PMC 2189082. PMID 3049910.

- Hayashi J, Hiromura K, Koizumi R, Shimizu Y, Maezawa A, Nojima Y, Naruse T (Mar 2001). "Platelet-activating factor antagonist, SM-12502, attenuates experimental glomerular thrombosis in rats". Nephron. 87 (3): 274–8. doi:10.1159/000045926. PMID 11287764.

- https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/3307#section=Pharmacology-and-Biochemistry

- CID 65889 from PubChem

External links

- Srf1 is Essential to Buffer Toxic Effects of Platelet Activating Factor

- Pharmacorama - PAF (Platelet Activating Factor)

- Platelet+Activating+Factor at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)