Aequi

The Aequi (Ancient Greek: Αἴκουοι and Αἴκοι) were an Italic tribe on a stretch of the Apennine Mountains to the east Latium in central of Italy who appear in the early history of ancient Rome. After a long struggle for independence from Rome, they were defeated and substantial Roman colonies were placed on their soil. Only two inscriptions believed to be in the Aequian language remain. No more can be deduced than that the language was Italic. Otherwise, the inscriptions from the region are those of the Latin-speaking colonists in Latin. The colonial exonym documented in these inscriptions is Aequi and also Aequicoli ("colonists of Aequium"). The manuscript variants of the classical authors present Equic-, Aequic-, Aequac-.[1] If the form without the -coli is taken as an original, it may well also be the endonym, but to date further evidence is lacking.

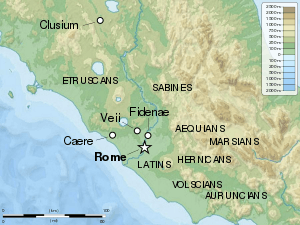

Historical geography

The historians made many entries concerning the wars between the Aequi and Rome; the geographers scarcely mention them. Pliny the Elder and Ptolemy both make the same brief statement: the towns of the Aequiculi were Cliternia or Cliternum and Carsoli or Carsioli respectively.[2][3] Pliny places them in Augustus' Regio IV; Ptolemy adds that they were to the east of the Sabini. By the time of the early Roman Empire, all vestige of the Italic Aequi was gone. The two cities mentioned had been Roman colonies. The forms mentioned in inscriptions from there are Carsioli and Cliternia.[1]

They occupied the upper reaches of the valleys of the Aniene, Tolenus and Himella, the last two being mountain streams running northward to join the Nera river.

History

According to Strabo, the Aequi were in existence when the city of Rome was founded.[4] They are first mentioned by Livy as an ancient nation from which the Romans borrowed the rites of declaring war.[5] Livy also mentions that the last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, made peace with the Aequi.[6]

They fought several wars against the Romans, among which was the Battle of Mount Algidus (458 BC). Their chief center is said to have been taken by the Romans about 484 BC.[7] and again about 90 years later.[8]

Records of fighting between Romans and Aequi become much sparser in the second half of the 5th century BC. Likely the Aequi had gradually become a more settled people and their raiding petered out as a result.[9]

In 390 BC, a Gaulish war band defeated the Roman army at the Battle of Allia and then sacked Rome. The ancient writers report that, in 389 BC, the Etruscans, Volsci, and Aequi all raised armies in the hope of exploiting this blow to Roman power. According to Livy and Plutarch, the Aequi gathered their army at Bolae. However, the Roman dictator, Marcus Furius Camillus, had just inflicted a severe defeat on the Volsci. He surprised the Aequian army and captured both their camp and the town.[10] According to Diodorus Siculus, the Aequi were actually besieging Bolae when they were attacked by Camillus.[11] According to Livy, a Roman army ravaged Aequian territory again in 388, this time meeting no resistance.[12] Oakley (1997) considers these notices of Roman victories against the Aequi in 389 and 388 to be historical, confirmed by the disappearance of the Aequi from the sources until 304. Owing to the dispute in the sources, however, the precise nature of the fighting around Bolae cannot be determined. Bolae was a Latin town, but it was also the scene of much fighting between Romans and Aequi, and it changed hands several times. Either an (unreported) Aequian capture followed by Roman recapture, or a failed Aequan siege, are therefore possible.[13]

The Aequi were not finally subdued until the end of the second Samnite war,[14] when they seem to have received a limited form of franchise.[15]

All we know of their subsequent political condition is that after the Social War the folk of Cliternia and Nersae appear united in a res publica Aequiculorum, which was a municipium of the ordinary type[16] located in what is now the municipality of Pescorocchiano. The Latin colonies of Alba Fucens (304 BC) and Carsioli (298 BC) must have spread the use of Latin all over the district; through it lay the chief (and for some time the only) route (Via Valeria) to Lucera and the south.

At the end of the Republican period, the Aequi appear under the name Aequiculi or Aequicoli, organized as a municipium, the territory of which seems to have comprised the upper part of the valley of the Salto, still known as Cicolano (from Latin Ager Aequicolanus). It is probable, however, that they continued to live in their villages as before. Of these, Nersae (modern Civitella di Nesce) was the most considerable. Remains include large polygonal terrace walls.

References

- Conway, Robert Seymour (1897). The Italic Dialects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 301–305.

- Pliny the Elder. "Book III, Chapter 12". Natural History.

- Ptolemy. "Book III, Chapter 1". Geography.

- Strabo. "Book V, Chapter 3, Section 2 (C 229)". Geography.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1:32

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1:55

- D.S. xi.140

- D.S. xiv.106

- Cornell, T. J. (1995). The Beginnings of Rome- Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c. 1000-264 BC). New York: Routledge. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-415-01596-7.

- Livy, 6.2.14; Plutarch, Camillus 33.1, 35.1

- D.S., xiv.117.4

- Livy, 6.4.8

- Oakley, S. P. (1997). A Commentary on Livy Books VI-X, Volume 1 Introduction and Book VI. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 352–353. ISBN 0-19-815277-9.

- Livy, 9:45, 10:1; Diod. xx. 101

- Cicero, Off. i. n, 35

- C.I.L. ix. p. 388