Roland Park, Baltimore

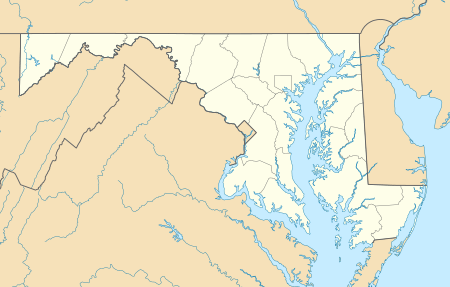

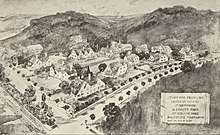

Roland Park is the first planned "suburban" community in North America, located in Baltimore, Maryland. It was developed between 1890 and 1920 as an upper-class streetcar suburb. The early phases of the neighborhood were designed by Edward Bouton and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.

Roland Park Historic District | |

| |

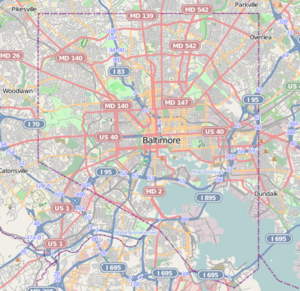

| Location | Irregular pattern between Belvedere Ave., Falls Rd., 39th St., and Stoney Run, Baltimore, Maryland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°20′57″N 76°38′05″W |

| Area | 700 acres (280 ha) |

| Built | 1890 |

| Architect | Olmsted, Frederick Law; Et al. |

| Architectural style | Late 19th And 20th Century Revivals, Late Victorian |

| NRHP reference No. | 74002213[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 23, 1974 |

History

Jarvis and Conklin, a Chicago investment firm, purchased 500 acres (200 ha) of land near Lake Roland in 1891 and founded the Roland Park Company with $1 million in capital. Not long after, the Panic of 1893 forced Jarvis and Conklin to sell the Roland Park Company to the firm of Stewart and Young. Despite the dire economics after 1893, Stewart and Young continued investment in the development.[2][3]

The Roland Park Company hired Kansas City developer Edward H. Bouton as the general manager and George Edward Kessler to lay out the lots for the first tract. They hired the Olmsted Brothers to lay out the second tract, and installed expensive infrastructure, including graded-streets, gutters, sidewalks, and constructed the Lake Roland Elevated Railroad. The company consulted George E Waring, Jr. to advise them on the installation of a sewer system. Bouton placed restrictive covenants on all lots in Roland Park. These included setback requirements and proscriptions against any business operations.[4] Bouton and the Roland Park Company initially intended to include covenants to exclude blacks from the development, but on advice of counsel did not include them in the deeds. The Roland Park Company would later insert these covenants into deeds in Guilford, Homeland and Northwood.[5]

It was a modern development, electricity for lighting throughout the neighborhood as well as gas for cooking and lighting. Water came from artesian wells dug up to 500 feet (150 m), nearly 50,000 feet (15,000 m) of water mains were constructed, in addition to 50,000 feet (15,000 m) of roadways, and 100,000 feet (30,000 m) of sidewalks.[6]

Bouton and some Baltimore investors purchased the interests of Roland Park and reorganized the company in 1903.[7]

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. cited Roland Park as a model residential subdivision to his Harvard School of Design students. Duncan McDuffie, developer of St. Francis Wood in San Francisco, called Roland Park "an ideal residential district." Jesse Clyde Nichols had found inspiration in Roland Park when he was planning the Country Club District of Kansas City.[8] Nichols continued to refer to Roland Park as an ideal residential development when he counselled other residential developers.[9]

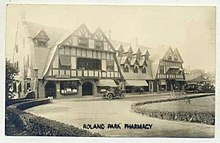

Roland Park Shopping Center

Roland Park Shopping Center (originally Roland Park Business Block)[10] was built at the corner of Upland Road and Roland Avenue in 1896 in the English Tudor style. Developed by Roland Park Company President Edward Bouton and designed by Wyatt and Nolting, it was originally planned as an apartment and office building with a “community room” for civic functions on the upper level.[11]

It opened in 1907 as shops.[12][13][14] It has been credited by Guinness World Records as the world's first shopping center (though some editions of Guinness incorrectly date it to 1896, when it was not yet a shopping center). Since it had only six stores, qualifying today as a strip mall, other, larger centers have received more recognition as “firsts”, such as Market Square in Lake Forest, Illinois (1916, the first uniformly planned neighborhood shopping center) and the Country Club Plaza (1923) in Kansas City, Missouri, the first uniformly-planned regional shopping center.[15][16][17]

Education

The neighborhood is within the bounds of Baltimore City Public Schools and is assigned to Roland Park Elementary/Middle School,[18] a K-8 school[19] that earned the Blue Ribbon for Academic Excellence from the state department of education in 1997 and 1998.

There are several private schools in the neighborhood: Friends School of Baltimore, Gilman School, Roland Park Country School, the Bryn Mawr School, Cathedral School, and Boys' Latin School of Maryland. In addition, St. Mary's Seminary and University is located in Roland Park.

There is also a branch of the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Roland Park.

Transportation

The Baltimore Light Rail's Cold Spring Lane Station is to the west, within walking distance of much of the neighborhood, just across Falls Road and running alongside the Jones Falls Expressway.

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Robert M. Fogelson (2005). Bourgeois Nightmares: suburbia, 1870-1930, p.59-60.

- Catharine F. Black (November 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Roland Park Historic District" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- Robert M. Fogelson (2005). Bourgeois Nightmares: suburbia, 1870-1930, p.60-63, 66-67.

- MacGillis, Alec (March 21, 2016). "The Third Rail". Places Journal. doi:10.22269/160321 – via placesjournal.org.

- Tom (2013-09-23). "History of Roland Park". Ghosts of Baltimore. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- Robert M. Fogelson (2005). Bourgeois Nightmares: suburbia, 1870-1930, p.64.

- Robert M. Fogelson (2005). Bourgeois Nightmares: suburbia, 1870-1930, p.63.

- Cheryl Caldwell Ferguson (Oct 2000). "River Oaks:1920s Suburban Planning and Development in Houston". Southwestern Historical Quarterly 104, p.121.

- "How Roland Park Was Founded and Developed". Baltimore Sun. December 27, 1908.

- "Roland Park Welcomes You". rolandparkhistory.org.

- Wallach, Bret (2005). Understanding the Cultural Landscape. Guilford Publications. p. 320. ISBN 9781593851194.

- Borden, Iain (2004). The City Cultures Reader. Routledge. p. 161. ISBN 9780415302456.

- Scharoun, Llisa (2012). American at the Mall. p. 7. ISBN 9780786490509.

- Rybczynski, Witold. City Life p.204 (Scribner 1996) (ISBN 978-0684825298)

- Urban Land Institute, The community builders handbook p. 125 (1954)

- Marx, Paul. Jim Rouse: capitalist/idealist, p.111 (2007) (ISBN 978-0761839446) ("...it has a small cluster of shops near its center. That group of shops is generally considered to be the very first shopping center in America.")

- "Elementary/K-8 Schools and Attendance Zones School Year 2014-15" and "Elementary/K-8 Schools and Attendance Zones School Year 2015-16" in: Appendix C." Baltimore City Public Schools. The 2014-2015 map is on p. 120 (PDF p. 10/34) and the 2015-2016 map is on p. 122 (PDF p. 12/34). Retrieved on July 10, 2016. Roland Park is no. 233 on both maps.

- Roland Park Public School http://rolandparkpublic.org/?page_id=2

External links

- Roland Park Historic District, Baltimore City, including undated photo, at Maryland Historical Trust, and accompanying map

- Community of Roland Park

- History of Roland Park

- Baltimore, Maryland, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Historical Marker Database, Roland Park, includes photos

- Roland Park: Most Fashionable and Pretentious Suburb - Ghosts of Baltimore blog