Federal Hill, Baltimore

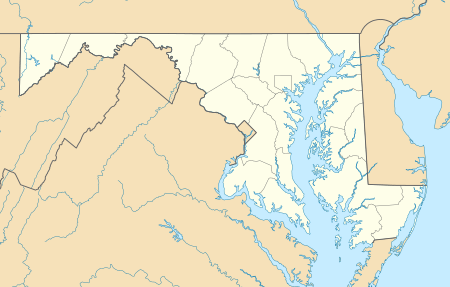

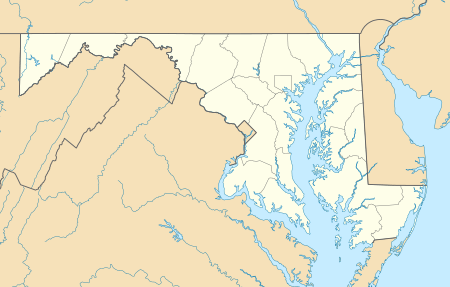

Federal Hill is a neighborhood in Baltimore, Maryland, United States that lies just to the south of the city's central business district. Many of the structures are included in the Federal Hill Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.[2][2][3][4] Other structures are included in the Federal Hill South Historic District, listed in 2003.[2]

Federal Hill Montgomery | |

|---|---|

Federal Hill Park | |

| Nickname(s): Fed | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Maryland |

| City | Baltimore |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT |

| ZIP code | 21230[1] |

| Area code | 410, 443, and 667 |

Federal Hill Historic District | |

| |

| Location | Bounded by Baltimore Harbor, Hughes, Hanover, and Cross Sts., Baltimore, Maryland |

| Coordinates | 39°16′44″N 76°36′36″W |

| Built | 1780 |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival, Federal |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000859[2] |

Federal Hill South Historic District | |

| |

| Location | Roughly bounded by Cross St., Olive St., Marshall St., Ostend St., Fort Ave. and Covington St., Baltimore, Maryland |

| Coordinates | 39°16′33″N 76°36′39″W |

| Area | 70 acres (28 ha) |

| Built | 1830 |

| Architect | Jackson Gott and others |

| Architectural style | Federal, Mid 19th Century Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 03001331[2] |

| Added to NRHP | December 22, 2003 |

| Added to NRHP | April 17, 1970 |

Location

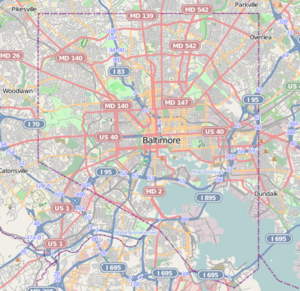

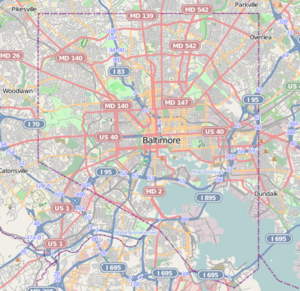

The neighborhood is named for the prominent hill that is easily viewed from the Inner Harbor area, to which the neighborhood forms the physical south boundary. The hillside is a lush green and serves as a community park. The neighborhood occupies the northwestern part of a peninsula that extends along two branches of the Patapsco River—the Northwest Branch (ending at the Inner Harbor) and the Middle Branch. This peninsula is generally referred to as the South Baltimore Peninsula, and includes the neighborhoods of Federal Hill, Locust Point, Riverside, South Baltimore, and Sharp-Leadenhall. While not physically a part of the peninsula, Otterbein is also included in the collection of neighborhoods which make up greater South Baltimore. Traditionally, Federal Hill was roughly triangular, bordered by Hanover Street to the west; Hughes Street, the harbor, and Key Highway to the north and east; and Cross Street to the south.

Amenities

The Cross Street Market, a historic marketplace built in the 19th century, continues to serve residents and is the primary social and commercial hub for the neighborhood. As of late 2016, the City of Baltimore has entered into an agreement with Caves Valley Partners to renovate Cross Street Market. The multimillion-dollar rebuild is anticipated to break ground during Spring 2017.[5]

The primary business district is bounded by Montgomery, Ostend, Light, Charles and Hanover Streets, and is home to a large number of restaurants of a wide range of taste, quality, and price, and many small shops as well as a few larger, more practical stores. The neighborhood is a popular destination for tavern goers and music lovers, with street festivals several times a year. These are organized through a very active neighborhood organization and business organization, as is the annual Shakespeare on the Hill series of summer performances in the park atop the actual Federal Hill. The neighborhood is also home to the American Visionary Art Museum and Maryland Science Center.

Significant and historic houses of worship include Christ Lutheran Church, Church of the Advent-Episcopal, Ebenezer African Methodist Episcopal Church, Light Street Presbyterian Church, Lee Street Baptist Church, Holy Cross Roman Catholic Church, and St. Mary's Star of the Sea Roman Catholic Church. Federal Hill is served by Federal Hill Elementary School, Thomas Johnson Elementary Middle School, Francis Scott Key Elementary and Middle School, and Digital Harbor High School. The public library is the Light Street Branch of the famous Enoch Pratt Free Library.

Federal Hill is also home to many popular retail, dining, and entertainment options all within walking distance for most neighborhood residents. With most daily needs covered by businesses within a few blocks of the community center, Federal Hill has emerged as a premier neighborhood for the increasing number of people choosing an urban lifestyle.

Transportation

Federal Hill is located conveniently to Interstate 95, Interstate 395, the Baltimore-Washington Parkway, and Charles and Light Streets, which provide the major north-south surface route through Baltimore. The western portions of the neighborhood are within walking distance of the Hamburg Street and Camden Yards stops on the Baltimore Light Rail. The Charm City Circulator is a free bus system that services central Baltimore and consists of four separate routes. Two of the routes, the Purple Route which runs from Penn Station to Federal Hill, and the Banner Route which runs from the Inner Harbor to Fort McHenry, service Federal Hill.

Early history

Early in the colonial period the area known as Federal Hill was the site of a paint pigment mining operation. The hill has several tunnels beneath its present parklike setting. On occasion a part of a tunnel will collapse causing the need to infill the area if the depression is near the surface of the edges of the hill.

From early in the history of the city, the hill was a public gathering place and civic treasure. The hill itself was given the name in 1789 after serving as the location for the end of a parade and a following civic celebration of the ratification of the new "Federal" constitution of the United States of America.[6] For much of the early history of Baltimore, the hill was known as Signal Hill because it was home to a maritime observatory serving the merchant and shipping interests of the city by observing the sailing of ships up the Patapsco River and signalling their impending arrival to downtown businesspeople.[7]

On the night of May 12, following the Baltimore riot of 1861, the hill was occupied in the middle of the night by a thousand Union troops and a battery under the command of General Benjamin F. Butler, who had entered the city, under cover of darkness and during a thunderstorm, from Annapolis via the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.[8] During the night, Butler and his men erected a small fort, with cannon pointing towards the central business district. Their goal was to guarantee the allegiance of the city and the state of Maryland to the United States government (with the implicit threat of force, should it have been necessary). This fort and the Union army presence persisted for the duration of the Civil War. A large flag, a few cannons, and a small Grand Army of the Republic monument remain to testify to this period of the hill's history.

Recent history

In the 20th century, Federal Hill was a working-class neighborhood, and by the late 1970s was yet another struggling Baltimore inner city neighborhood, with increasing crime, racial tension, depressed property values, and an aging and decaying housing stock. Many of the industrial jobs, particularly in the shipyards and factories along the south shore of the Patapsco River, which had long provided the main source of employment for neighborhood residents were in the process of disappearing. The Bethlehem Steel shipyards on the east side of the hill were one of the last to close, in the early 1980s. The nationally recognized urban homesteading program in nearby Otterbein, begun in 1975, helped spur interest among individuals and businesses in rehabilitating homes in Federal Hill, and it soon became a hotbed of investment and rehabilitation, particularly by young professional baby boomers who had grown up in the suburbs but worked downtown.[9]

The investment and growth throughout downtown and especially at the Inner Harbor through the 1980s and 1990s only increased the popularity of Federal Hill living over the decades following the initial reinvestment period. A second period of intense investment and rising property values began in the mid 1990s. This second stage of neighborhood investment has included not just single-family home rehabilitation but increasingly large development projects on former industrial sites, particularly on the edges of the neighborhood around the water's edge. Within the core of the neighborhood itself, there has been an influx of new restaurants and shops. The city's population grew 0.6% in 2006 for the first time since the 1950s with much of the growth focused in Federal Hill. Streets that used to have vacant houses on every block have now been fully renovated. Many families have moved into these houses.

Demographics

As of the census[10] of 2000, there were 2,400 people living in the neighborhood. The racial makeup of Federal Hill was 87.3% White, 9.0% African American, 0.2% Native American, 2.1% Asian, 0.6% from other races, and 1.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.3% of the population. 55.6% of occupied housing units were owner-occupied. 8.8% of housing units were vacant.

82.5% of the population is employed and 4.0% is unemployed, with the remainder not in the labor force.[11] The median household income was $62,466. About 1.0% of families and 7.0% of the population were below the poverty line.

21.8% of Federal Hill residents walked to work.

References

- http://www.zipmap.net/Maryland/Baltimore_city/Z_Hampden-Woodberry-Remington.htm

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Mrs. Preston Parish (n.d.). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Federal Hill Historic District" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- Betty Bird; Jennifer Goold; Julie Darsie (March 2003). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Federal Hill South Historic District" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- "City reaches deal with Caves Valley Partners for overhaul of Cross Street Market".

- "Federal Hill Baltimore City". Baltimore Metro Real Estate. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "Federal Hill Park". US News – Travel. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Improvised War, 1861–1862 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1959), p. 87.

- "Federal Hill".

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "American Community Survey" (PDF). American Community Survey. Retrieved 2019-03-23.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Federal Hill, Baltimore. |

- Illustrated Walking Tour Interactive Map Official website for Friends of Federal Hill Park

- Official site for Historic Federal Hill Main Street

- A description of Federal Hill Park with interactive walking tour map

- Federal Hill Baltimore Guide

- Demographics from Neighborhood Indicators Alliance

- Baltimore, Maryland, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Federal Hill Historic District, Baltimore City, including undated photo and boundary map, at Maryland Historical Trust

- Federal Hill listing at CHAP includes map

- Federal Hill South Historic District, Baltimore City, including undated photo and boundary map, at Maryland Historical Trust

- Federal Hill South listing at CHAP includes map