Pigtown, Baltimore

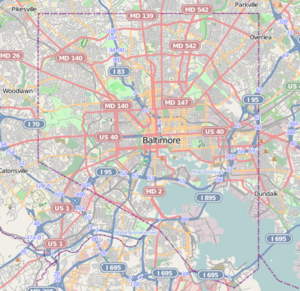

"Pigtown", also known as "Washington Village", is a neighborhood in the southern area of Baltimore, bordered by Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard to the east, Monroe Street to the west, Russell Street to the south, and West Pratt Street to the north.[1][3] The neighborhood acquired its name during the second half of the 19th century, when the area was the site of butcher shops and meat packing plants to process pigs transported from the Midwest on the B&O Railroad; they were herded across Ostend and Cross Streets to be slaughtered and processed.[4]

Pigtown Historic District (aka "Washington Village") | |

Pigtown Historic District, December 2011 | |

| |

| Location | Roughly bounded by McHenry, Ramsay, West Barre, South Paca, West Ostend, Wicomico, Bush and Bayard Streets, plus B&O Railroad (CSX/Amtrak), Baltimore, Maryland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°16′49″N 76°37′56″W |

| Area | 50 acres (20 ha), .325 sq mi[1] |

| Architectural style | Federal, Greek Revival, Italianate |

| NRHP reference No. | 06001177[2] |

| Added to NRHP | December 28, 2006 |

Pigtown's annual festival famously features a pig race, called "The Squeakness", to commemorate its history.[5]

Pigtown has long been considered one of Baltimore's most promising neighborhoods due to its proximity to the I-95 corridor, the University of Maryland Medical Center, Camden Yards, Ravens Stadium, the Inner Harbor, and Downtown Baltimore.[6] New developments on the eastern edge of the neighborhood of luxury townhomes were stalled after the 2008 market crash but eventually resumed and have continued into 2016. Other parts of the neighborhood contain classic Baltimore-style rowhouses, often with 1950s-era formstone facades on brick fronts.

Pigtown has a relatively diverse population, which, besides its longtime residents, includes a sizeable graduate student population. Because of its proximity to Interstate 95, the Baltimore-Washington Parkway, and its low housing costs, Pigtown also has a great number of commuters to Washington, D.C and Fort George G. Meade.

History

The area where Pigtown is now located was originally part of the Mount Clare plantation, a 2,368-acre estate owned by Dr. Charles Carroll in the 18th century. Carroll built one of Maryland's first iron foundries on the property, which operated the largest pig iron furnace in the colonies prior to the American Revolution. Dr. Carroll was a cousin of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, who signed the Declaration of Independence.[7][8][9]

In 1827, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was founded in Baltimore. Ground was broken on the Mount Clare property in 1828, with the first stone laid by Charles Carroll of Carrollton, at the age of 90. Initially providing service between Baltimore and Ellicott Mills (now Ellicott City, Maryland), the railroad began operating along West Pratt Street on May 22, 1830. The horsedrawn cars of the early B&O Railroad were the nation's first regular passenger rail.[8][10]

Construction of the first houses to the north and south of the railroad yards began in 1833. A community of railroad workers grew along Columbia Avenue (now Washington Boulevard) in the 1840s, followed by industrial development in the 1850s and 1860s. Slaughter houses located near the railroad yards earned the area its name as Pigtown as workers herded pigs for slaughter and processing to shops and packing plants across the streets from the rail cars.[8]

Although official records have identified the neighborhood as Washington Village at various points since the 1970s, it has been consistently labeled as Pigtown since 2006 at the insistence of community groups such as Southwest Community Council, Inc.[8]

Historic landmarks

Pigtown has several historic landmarks, including some national landmarks. Patrick's of Pratt Street, which has operated at 934 West Pratt Street for more than 160 years, claims to be "America's Oldest Irish Pub".[11] The Bayard Station valve house at 1415 Bayard Street, built in 1885 by the Chesapeake Gas Company to distribute coal gas in Baltimore, now serves as home to Housewerks, an architectural salvage store.[12] Pigtown is also home to the historic B&O Railroad Museum, which houses exhibits of historic significance to American railroading and items specific to the Pigtown community.

Mount Clare Mansion, a brick Georgian plantation house built in 1763, is the oldest remaining Colonial-era structure in Baltimore.[13] It was purchased by the city government in 1890, along with 70 acres of land, for use as a park. Located at 1500 Washington Boulevard, the former home of Dr. Charles Carroll has been maintained as a museum by the Maryland chapter of The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America since 1917.[14]

Culture

The blue collar culture of Pigtown began with the individuals who worked on the B&O Railroad and German immigrants who opened butcher shops in the neighborhood. Community organizations have emphasized the importance of the neighborhood's history and blue collar origin as they rebuffed attempts to rename it Washington Village.[8]

Pigtown celebrates its culture yearly during the Pigtown Festival, which features local food, entertainment and "Squeakness", a race featuring pigs. The pig race pays homage to the neighborhood's beginning with the railroad, railroad workers and German butchers.[5]

Many white residents of Pigtown are out-migrants or descendants of out-migrants from Appalachia, particularly West Virginia and Western Maryland. Poor white Appalachian residents of Pigtown report discrimination from the police on the basis of class. Some poor white residents of Pigtown allege that while poor black people in Pigtown and the nearby neighborhood of Sandtown experience more discrimination due to the combination of racism and classism, poor whites nonetheless experience targeting and harassment from the police. According to David Simon, a police reporter from the Baltimore Sun, a nickname for Pigtown among police officers is "Billyland", derived from the term hillbilly, a derogatory term for poor white Appalachians.[15]

Horseshoe pit

Since the 1970s, an empty lot at the corner of Ward and Bayard Streets has served as the community horseshoe pit. Its significance in the community is commemorated by a mural, painted on a building beside the lot, about 15 years after the first horseshoe stakes were planted there. In 2007, the 12-by-60 foot area was sold by the city government to a developer. It was repurchased by the city in 2010, and is now preserved and maintained as the community horseshoe pit by Baltimore Green Space, a local nonprofit organization. The first Annual Horseshoe Tournament at the Pit In Pigtown was held in 2011.[16][17]

Tailgating Parties

Another empty lot, this time on the corners of Ostend and Wicomico streets serves as the location of tailgate parties before Ravens football games. The lot has an area of 35,718 square feet and can hold around twenty trucks and tents during those tailgating parties.

Attractions

Mobtown Ballroom draws a diverse crowd of hundreds of people from surrounding towns and neighborhood to Pigtown for its swing dance, Belly dance, and Lindy Hop lessons.[18]

The B&O Railroad Museum forms the northern boundary of Pigtown. It has the largest collection of 19th Century locomotives in the U.S.

Second Chance, Inc. is a 200,000 square foot store that sells reclaimed furniture and materials.[19]

Demographics

Pigtown is a diverse region of Baltimore, containing many races and income brackets. Pigtown is one of the many stops on the Gwynn Falls trail connecting more than thirty Baltimore neighborhoods. It is home to the historic Carroll Park that consists of baseball fields, football fields, basketball courts, a skate park, playgrounds, and Mount Clare. The area also consists of a multitude of warehouses and industrial areas. The community contains varying types of architecture in the neighborhood's business and residential buildings.

In its community statistical area profile for the Pigtown area, the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance reported a population of 5,503 residents in the neighborhood, living in approximately 2,740 homes during 2010. These homes consisted of newly built town homes, older row houses, condominiums and apartments, with an average of 2.4 residents per household. By 2012, neighborhood housing was estimated to have increased to 2,760 homes. Its population mix in 2010 was estimated as 49 percent African American, 39 percent white, 5.3 percent Hispanic and 6.7 percent other, giving the area a 61.2 diversity index, well above the 54.5 citywide index. The majority (59.9 percent) of the area's population was reported in the age range of 25 to 64. Median income of $44,993 was estimated for 2010, but 30.5 percent of the area's households were under $25,000 and 25.3 percent were considered below the poverty line. Its poverty rate was significantly greater than the citywide rate of 17.7 percent.[20]

The 50-acre community statistical area measured by the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicator's Alliance is somewhat larger than Pigtown, including the neighborhoods of Carroll Park and Barre Circle.[20]

During 2012, the Pigtown community statistical area experienced an unemployment rate of 12.7 percent, somewhat better than the citywide rate of 13.9 percent for the year.[20]

Transportation

Eastern portions of Pigtown are within walking distance of Camden Station, served by both the Baltimore Light Rail and the MARC Camden Line. The neighborhood's proximity to Camden Station, Interstate-95 and the Baltimore-Washington Parkway, provides residents with access to important regional commuter routes.

Route 36 (MTA Maryland) provides the neighborhood with local bus service along Washington Boulevard, on its daily route between Northern Parkway (north) and Lansdowne (south).[21]

Education

Three elementary schools are located in Pigtown: George Washington Elementary, Charles Carroll Barrister Elementary, and Southwest Baltimore Charter School. There are two middle schools in Pigtown: Mount Clare Christian School and Franklin Middle. No high schools are located in the neighborhood.

In 2011, 88.87 percent of the children in Pigtown were receiving free or reduced price school lunches, and 15 percent were enrolled in special education programs. The racial composition of Pigtown students was 76.6 percent African-American, 17.2 percent white, and 2.1 percent Hispanic. Thirty-two percent of Pigtown's adult residents had a bachelor's degree or higher in 2011, while another 41 percent had at least a high school diploma, but 26 percent had not completed high school.

Crime rate

The overall crime rate in the Pigtown community statistical area (which includes Carroll Park and Barre Circle), at 121.4 per thousand residents for the year of 2012, was markedly higher than the citywide average 61.8 per thousand, reflecting problems associated with poverty. Violent crime in Pigtown was 23.1 per thousand, while the city saw an average of 14.7 per thousand. The city had a property crime rate of 47 per thousand residents in 2012, but the rate in Pigtown hit 98.3. Juvenile arrests were at a rate of 91.7 per thousand in Pigtown, compared to the citywide rate of 79.2 in 2012.[20]

References

- "Washington Village neighborhood in Baltimore, Maryland". City-Data.com. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "Pigtown/Washington Village". Live Baltimore. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- "History". Pigtown Main Street. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- "Pigtown Festival". Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- Sun, Baltimore. "More businesses head to Pigtown". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved 2016-03-03.

- Michael Anft (April 15, 2005). "Washington Village/Pigtown". The Baltimore Sun.

- "The History of Pigtown's Name" (PDF). Historic Pigtown. Citizens of Pigtown Community Association. September 2007.

- Mary Ellen Hayward (February 2006). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Pigtown Historic District" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- Harwood, Herbert W., Jr. (1979). Impossible Challenge. Baltimore: Bernard, Roberts and Co. pp. 12–21. ISBN 0-934118-17-5.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Best of Baltimore 2007". Baltimore Magazine. August 2007.

- "The History of Bayard Station". Housewerks. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- "Mount Clare". National Historic Landmark. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- "Mount Clare". National Park Service. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- "Baltimore's poor white residents also feel sting of police harassment". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- Jonathan Pitts (June 25, 2011). "Horseshoe pit helps build Pigtown's neighborhood spirit". The Baltimore Sun.

- "Pigtown Horseshoe Pit". Baltimore Office of Sustainability. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- Sun, Baltimore. "Class of the Month: Belly dancing at Mobtown Ballroom". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved 2016-03-03.

- "About Us - Second Chance Inc". Second Chance Inc. Retrieved 2016-03-03.

- "Vital Signs 12 Community Statistical Area (CSA) Profiles: Washington Village" (PDF). Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- "Route 36 Local Bus Schedule" (PDF). MTA Maryland. February 9, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pigtown, Baltimore. |

- Pigtown Festival

- Pigtown Historic District, Baltimore City, including photo from 2005 and boundary map, at Maryland Historical Trust

- Citizens of Pigtown