Rila Monastery Nature Park

Rila Monastery Nature Park (Bulgarian: Природен парк „Рилски манастир“) is among the largest nature parks in Bulgaria spanning a territory of 252.535 km2 in the western part of the Rila mountain range at an altitude between 750 and 2713 metres. It is situated in Rila Municipality, Kyustendil Province and includes forests, mountain meadows, alpine areas and 28 glacial lakes. With a little more than 1 million visitors, it is the second most visited nature park in the country, after Vitosha Nature Park.[1]

| Rila Monastery Nature Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

A view of the nature park | |

| |

| Location | Rila Municipality, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria |

| Nearest city | Rila |

| Coordinates | 42°08′52″N 23°37′38″E |

| Area | 252.532 km2 |

| Established | 1992 |

| Visitors | 1 002 204 (in 2008) |

| Governing body | Ministry of Environment and Water |

It was established in 1992 as part of the newly founded Rila National Park. In 2000 some territory of the national park was reassigned to the Rila Monastery and was recategorized as a nature park because by law all lands in national parks are exclusively state owned. Nowadays most of the park is owned by the monastery. The park includes one nature reserve, Rila Monastery Forest, with an area of 36.65 km2 or 14% of its total territory.[2]

The park falls entirely within the Rodope montane mixed forests terrestrial ecoregion of the Palearctic Temperate broadleaf and mixed forest. There are approximately 1400 species of vascular plants, 282 species of mosses and 130 species of freshwater algae. The fauna is represented by 52 species of mammals, 122 species of birds, 12 species of reptiles, 11 species of amphibians and 5 species of fish, as well as 2600 species of invertebrates. The endemic Rila oak (Quercus protoroburoides) inhabits only the Rilska River valley within the park's boundaries and is of special conservation significance.

The park is named after the Rila Monastery, a cultural and spiritual centre of Bulgaria, founded during the First Bulgarian Empire by the 10th century ascetic and saint John of Rila. It was designated an UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983.

Park administration and ownership history

Rila Monastery Nature Park is administered by a directorate based in the town of Rila and subordinated to the Executive Forest Agency of the Ministry of Environment and Water of Bulgaria.[3][4] The directorate implements the state policy for the management and control of the protected area and controls the coordination between the owner of the larger part of the park, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, and the state institutions. It maintains the ecosystems and the biodiversity and encourages environmentally-friendly tourism.[2] The park falls within the International Union for Conservation of Nature management category V (protected landscape/seascape). Its territory is included in the European Union network of nature protection areas Natura 2000 under the code Rila Monastery BG0000496.[5]

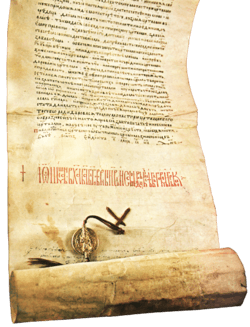

The territory of the modern park has been closely connected with the Rila Monastery ever since its foundation in the 10th century. The Bulgarian emperors Ivan Asen II (r. 1218-1241) and Kaliman I (r. 1241-1246) donated to the monastery lands, forests and pastures in the valley of the river Rilska, as well as in the regions of Kyustendil, Blagoevgrad, Melnik and Razlog.[6] Emperor Ivan Shishman (r. 1371-1395) reconfirmed the monastery's privileges and further increased its territory with the Rila Charter which describes the borders of the lands.[6] After the Liberation of Bulgaria from Ottoman rule in 1878, the territory of the modern park was under the jurisdiction of the Rila Monastery until 1947, when it was nationalized by the government of the People's Republic of Bulgaria.[7] In 1997 the government adopted legislation to allow the restitution of the nationalized forests and in 2000 the former possessions of the monastery were restored.[8]

Geography

Overview

Rila Monastery Nature Park is situated in the Rila mountain range in the south-west of the country. It is entirely located in Rila Municipality of Kyustendil Province with coordinates between 42°03' and 42°11' northern latitude and 23°12' до 23°32' eastern longitude. The park encompasses the western part of the mountain within the catchment area of the rivers Rilska and Iliytsa.[9] Of the total area of 252.535 km2, forests cover 143.707 km2 and alpine meadows – 130 km2.[10] By road the park is accessible through the III-107 third class road which begins from the I-1 first class road at the town of Kocherinovo.[11]

Relief and geology

The zones of the Rila mountain range that fall within the park are formed mainly by metamorphic rocks – gneiss, biotite gneiss, amphibolite, mica, schist and marble, bordering to the north and to the east with coarse-grained granite, granite-gneiss, smooth-grained granite and pegmatite veins.[12] The metamorphic mantle has a general inclination to the south-west by the magnitude of 35 to 60°.[12]

The average altitude of the park is 1750 m and the highest summit is Rilets at 2713 m.[13] The valley of the river Rilska from the Fish lakes to the Kirilova meadow divides the territory of the park into two principal orographic crests, Skakavishko and Riletsko. They are connected with the main orographic and hydrographic junction of the mountain, Kanarata peak (2691 m), through which passes the watershed between the Black Sea and Aegean Sea catchment areas.[14]

The glacial relief is typical for the highest zone of the park and dates from the Pleistocene. During the glacial periods the limits of the permanent snow cover were at 2200 m. The glaciers melted down 10–12000 years ago. They were of Alpine type and descended into the valleys reaching as low as 1200–1300 m. Evidence of that limit are the moraines along the river Rilska at 1250 m altitude.[15] The most typical features from that period are the cirques found in the glacial valleys of Rilska and its tributaries. Many cirques contain lakes, such as the Smradlivo Lake, the largest glacial lake in the Balkans, or the Fish Lakes.[15]

Climate

The high vertical amplitude and the western orientation of the valleys of the rivers Rilska and Iliyna to the Struma valley have a considerable influence on the climate. The rugged terrain and the thermocline of 0.7 °C per 100 m determine the significant climate difference between the regions with lower and higher altitude in the park.[16] The mean temperature at the Rila Monastery (1175 m altitude) in January is -2.8 °C and in June is 16 °C, with minimum and maximum temperature of -25 °C and 36 °C respectively. The mean annual temperature at the altitude of 2000–2500 m varies in the interval of 0 to 5 °C; it is negative above 2500 m.[16] Rila Monastery Nature Park is characterized with frequent temperature inversions, i.e. increase in temperature with height, due to the penetration of warm and often more humid air masses of Mediterranean origin from the Struma valley to the west.[17] The number of days with temperature inversions varies between 200 and 220 annually.[17]

The annual precipitation in the lower parts of the park is 700–800 mm. At the altitude of 1000–2200 m it varies between 1050 and 1200 mm, and at higher altitudes the precipitation decreases. The driest month is February and the most humid months are May and June.[17] The annual evaporation is 450–500 mm at the altitude of 800–1000 m and 350–400 mm at 1000–2200 m, which determines a positive water balance.[17] At higher altitudes the humidity of the air is 80–85 % and falls to 30% in the cold and dry winter days.[17] Due to the orientation of the slopes in the park, permanent snow cover is formed by mid-December. The duration of the snow cover at around 1200 m is 160–180 days and reaches 190–200 days at higher altitudes.[18] In March the thickness of the snow cover is 60–70 cm in the lower areas of the park but it can surpass 200 cm in the alpine zone.[18] Melting begins during the first ten days of April. In the cirques the snow firn, which forms specific natural habitat, melts in mid-June.[18]

Hydrology

Rila Monastery Nature Park contains 28 glacial lakes situated at altitudes above 2200 m. They provide a source for numerous streams and creeks which form the park's main river, the 51 km-long Rilska River.[19] The river rises at the Fish Lakes and flows into the Struma near the town of Kocherinovo. It has a catchment area of 390 km2 and a total annual discharge of 241.9 million m3.[19] Most of the water flow comes from the left tributaries, situated on the northern slopes of the ridge. The main water source is the snow that accumulates in the winter months.[20]

Most of the park's lake groups fall within Rilska's catchment zone – Smradlivite Lakes, a group of three lakes that includes Bulgaria's largest glacial lake with an area of 21.2 ha, a volume of 1.72 million m3 and a depth of 28 m;[20] the Black Lake; Devil's Lake (seven lakes); Monastery Lake (three lakes); Marinkovsko Lake; the Dry Lake; and the Fish Lakes, the largest lake complex in the park, consisting of four entities.[21] The catchment area of the river Iliyna includes the four Karaomerichki Lakes, Mramorets Lake and Lake Kamenitsa.[22]

Biology

Ecosystems and habitats

Forest ecosystems cover 70% of the park's territory. The lowest zones (800–1500 m) are occupied with beech forests consisting primarily of European beech (Fagus sylvatica), riparian deciduous forests dominated by grey alder (Alnus incana) and mixed forests of beech, common hornbeam (Carpinus betulus) and hop hornbeam (Ostrya carpinifolia). Above these ecosystems are located xerothermic oak forests, dominated by sessile oak (Quercus petraea), whose upper zones are covered by European beech, European silver fir (Abies alba) and Bulgarian fir (Abies borisii-regis). Coniferous ecosystems occupy altitudes between 1300 and 2200 m and consist of Norway spruce (Picea abies), Macedonian pine (Pinus peuce), Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and firs.[23] Secondary ecosystems that replace primeval forests cover 5% of the park consist mainly of common aspen (Populus tremula), silver birch (Betula pendula) and common hazel (Corylus avellana) replacing spruce and pine forests.[23] The park is the only habitat of a local endemic tree species, the Rila oak (Quercus protoroburoides) that grows only in three localities along the Rilska River valley.[24]

Alpine ecosystems cover 20% of the park's area at 2200–2500 m and are dominated by dwarf mountain pine (Pinus mugo). Other species in these ecosystems are green alder (Alnus viridis), Waldstein's willow (Salix waldsteiniana), common juniper (Juniperus communis), Chamaecytisus absinthioides and Festuca valida.[25] Grass ecosystems consist primarily of perennial grasses, such as Sesleria comosa, Festuca riloensis, Agrostis rupestris, etc. A specific element of these ecosystems is the calcareous vegetation zone with species like Elyna bellardii, Carex kitaibeliana, Salix retusa, Salix reticulata, Dryas octopetala, etc.[25]

Rila Monastery Nature Park falls within the Rodope montane mixed forests terrestrial ecoregion of the Palearctic Temperate broadleaf and mixed forest. The park includes 85 habitats based on the Coordination of Information on the Environment (CORINE) classification methodology, or 21% of all habitats in Bulgaria. Of them, 37 are found exclusively in the forest zone, 34 in the Alpine zone and 14 are found in both zones.[26]

Flora

The park is home to 1400 species of vascular plants, or 38.88% of Bulgaria's total diversity.[27][28] The highest number of species is concentrated in the coniferous and subalpine zones. The highest concentration of species is found in the Rila Monastery Forest Reserve, the valleys of the rivers Iliyna and Radovichka, and at the foothills of Kalin peak. The least diverse zone is the Alpine, with 250–300 species.[28][29] There are five florogeographic components – Eurasian (158 species), Cirqumboreal (135 species, including glacial relicts), Central European (125 species), Mediterranean (307 species) and endemic (123 species, including 6 local, 27 Bulgarian and 90 Balkan endemic species).[29] The most common local endemics are Rila primrose (Primula deorum) and Rila oak (Quercus protoroburoides), and from the Bulgarian ones – Jasione bulgarica, Alopecurus riloensis, Silene velenovskyana and Rila violet (Viola orbelica).[29] Balkan endemic species include Bulgarian avens (Geum bulgaricum), yellow mountain lily (Lilium jankae), Fritillaria gussichiae, etc.[30] The number of relict species is 110, or 7.86% of the park's vascular flora, including 77 glacial and 33 Tertiary relicts.[31] 96 species are registered in the Red Book of Bulgaria and 14 are included in the IUCN Red List.[31]

There are 35 tree species in the park, which is 32% of the 109 tree species found in Bulgaria. Coniferous woods form 68.3% of the forests and deciduous woods make up the other 31.7%. The distribution by species is as follows: European beach – 21.6%, dwarf mountain pine – 17.4%, Norway spruce – 16.7%, Scots pine – 14.6%, silver fir and Bulgarian fir – 12.7%, Macedonian pine – 6.9%, sessile oak and Rila oak – 4.6%, silver birch – 1.5%, common aspen – 1.3%, grey alder – 1.1%, other – 1.6%.[28][32] The average age of the woods is 99 years; centenary forests form 53.7% of the total forest mass.[33]

There are 164 moss species, or 58% of the known diversity in the Rila mountain range. The highest moss concentrations are found in and along the rivers Rilska and Iliyna, their tributaries and the wet meadows in the Alpine zone.[28][34]

Fungi

The number of fungi species in the park is 306.[35] They are classified into 3 classes, 26 orders, 54 families and 140 genera. The most common order are Agaricales with 109 species and the most diverse families are Tricholomataceae (62 species), Russulaceae (40 species), Cortinariaceae (31 species), Coriolaceae (19 species) и Boletaceae (15 species).[36] The species distribution by forest ecosystems is as follows: beech (69), alder (47), spruce and fir (80), and Macedonian pine (36).[36]

The species with highest conservation importance is Suillus sibiricus which in Europe grows only in the forests of Macedonian pine in Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia, and in the forests of Swiss pine in the Alps.[37] The number of edible mushrooms is 38, including Agaricus augustus, mosaic puffball (Handkea utriformis), peppery milk-cap (Lactifluus piperatus), weeping milk cap (Lactifluus volemus), charcoal burner (Russula cyanoxantha), Russula grisea and Russula olivacea.[37]

Fauna

Rila Monastery Nature Park is inhabited by 202 vertebrate species.[38][39] There are 52 species of mammals. The number of bats species is 15, or 50% of the diversity in Bulgaria and 45% in Europe. There are 20 species of small mammals: 9 Insectivora, 1 Lagomorpha and 13 Rodentia. Of them the European snow vole is a relict.[40] The large mammals include 13 Carnivora and 4 Artiodactyla species.[39] The most typical mammals in the park are the grey wolf, golden jackal, red fox, brown bear, European badger, European polecat, European otter, European pine marten, beech marten, wildcat, wild boar, red deer, roe deer and chamois.[41]

The avian species in the park are 122, of which at least 97 are nesting. Important birds of prey with high conservation value include the griffon vulture, cinereous vulture, eastern imperial eagle and booted eagle.[42] The park is one of the two nesting localities in the country of the lanner falcon and the common rosefinch.[42] Rila Monastery Nature Park is an important sanctuary of the hazel grouse, rock partridge, western capercaillie, Eurasian pygmy owl, boreal owl, black woodpecker, white-backed woodpecker, red-breasted flycatcher, wallcreeper, Alpine accentor and Alpine chough.[42] Most of the listed species have at least 5% of their total national population in the territory of the park.[42]

There are 12 reptile species, not counting the spur-thighed tortoise which breeds just outside the park's limits near the village of Pastra. The largest diversity is found in the lower zones – 10 species. Rila Monastery Forest Reserve is home to 5 reptile species.[43] The population of the Aesculapian snake is of European importance.[44] Of national importance are the populations of the slowworm, viviparous lizard, smooth snake and common European viper.[45] The amphibians are represented with 11 species, with highest diversity in the wet deciduous forests and the forest streams. Rila Monastery Forest Reserve is the most important area for amphibians conservation.[43] Three species have a population of national importance: the Alpine newt, yellow-bellied toad and common frog.[45]

The ichthyofauna includes 5 fish species: common minnow, Maritsa barbel, brown trout, rainbow trout and brook trout. The limited number of species is determined by the predominant bodies of water – glacial lakes, streams and upper river courses, which are inhabited by few fish species. Most of the fishes are found in the river Rilska.[43]

The invertebrate fauna is poorly studied. There are between 2475 and 2600[39] identified species, including 1703 insects, but their actual number is estimated to be 6500–7000.[46] The main hotspots are Rila Monastery Forest Reserve, the area around the Fish Lakes to the east and the Kalin reservoir, as well as the areas around the river Radovichka and Bukovo bardo.[46] There are 96 rare, 85 endemic and 146 relict species; 116 are included in worldwide or European lists of endangered animals.[46] Some of the endangered species include beetles: Calosoma sycophanta, Carabus intricatus, Morimus funereus; net-winged insects: Libelloides macaronius; ants: Formica lugubris, Formica pratensis, Formica rufa; butterflies: Parnassius apollo, Parnassius mnemosyne, Euphydryas aurinia, Polyommatus eroides, Apatura iris, Carterocephalus palaemon, Colias caucasica, Erebia rhodopensis, Charissa obscurata, Limenitis populi, Melitaea trivia, Zerynthia polyxena, etc.[47]

Cultural and historical heritage

The principal architectural monument in the park is Rila Monastery, situated at an altitude of 1147 m and declared a UNESCO's world heritage site in 1983.[1][48] The Monastery is considered to be a cultural and spiritual centre of Bulgaria.[48] With its architecture and frescos Rila Monastery represents a masterpiece of the creative genius of the Bulgarian people and has exerted considerable influence on architecture and aesthetics within the Balkan area.[49]

The monastery was founded by the medieval Bulgarian hermit and saint John of Rila during the reign of emperor Peter I of Bulgaria (r. 927–969).[50] It developed into one of the main cradles of Bulgarian culture, literature and spirituality, and was richly donated by several Bulgarian emperors. In the 13th century the relics of John of Rila were transferred to the capital Tarnovo but after the fall of the Bulgarian Empire under Ottoman rule they were returned to the monastery in 1469.[49] Rila Monastery remained an important centre for pilgrimage. In the 18th century it became one of the main hubs of the Bulgarian National Revival.[49][50]

The monastery complex covers an area of 8,800 m2 and consists of a church, a defensive tower and monastic apartments encircling an inner yard. The exterior of the complex resembles a fortress with its high stone walls and little windows. The oldest surviving structure is the 23 m high Hrelyo's Tower, constructed in 1334–1335 by orders of the feudal lord Hrelyo. The five-storey tower contains a chapel dedicated to the Transfiguration and decorated frescoes dated from the second half of the 14th century.[49][51] The other medieval edifices were destroyed in a fire in the early 19th century. The five-domed Church of Our Lady of the Assumption was built in 1833. It is covered with spectacular frescoes and houses a magnificent carved wooden iconostasis, executed in 1842.[49][51] The residential part contains about 300 chambers, four chapels, an abbot's room, a kitchen, a library housing 250 manuscripts and 9,000 old printed books, and a donor's room. They have spacious verandas, wood-carving decoration, paintings and furniture.[49]

The centrepiece of the monastery's museum is Rafail's Cross, a wooden cross made from a single piece of wood measuring 81×43 cm. It contains 104 biblical scenes and 650 miniature figures. The cross was carved by a monk named Rafail using fine burins and magnifying lenses. The whole process took 12 years and the monk had gone blind in 1802 when the work was finished.[52]

Tourism

Tourism is the most important sector in the park and has the largest potential to be a source for sustainable income. Rila Monastery Nature park is the second most visited nature park in Bulgaria after Vitosha, which is situated next to the nation's capital Sofia.[53] Around 96% of all adult Bulgarians have visited the Rila Monastery at least once; of them 60% have come more than twice.[54] In 2008 the park was visited by 1,002,204 people.[1] Of them, approximately 1/3 are foreign citizens. More than 2/3 of the visitors come to the park for a one-day trip without staying overnight. Around 90% of all tourists visit the monastery.[55] Half of the tourists arrive in two of the summer months, July and August.[56] More than 2/3 arrive by car via the III-107 third class road, the park's only highway access; the rest come by foot from Rila National Park.[57]

The most popular routes through the park are: Rila Monastery–Kirilova polyana–Dry Lake–Kobilino branishte; Rila Monastery–Fish Lakes–Smradlivo Lake; Rila Monastery–Malyovitsa; Rila Monastery–Seven Rila Lakes and E4 European long distance path.[1]

See also

Citations

- "Rila Monastery Nature Park: Publications. Basic Information". Trans-Border Network. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery Nature Park: Basic Information". Trans-Border Network. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery Nature Park". Forest Agency to the Ministry of Environment and Water. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery Nature Park: Administration". Trans-Border Network. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery". Information System on the Protected Areas under Natura 2000. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Yankov 2004, p. 9

- Yankov 2004, pp. 9–10

- Yankov 2004, p. 10

- Yankov 2004, p. 3

- Yankov 2004, p. 7

- Yankov 2004, p. 87

- Yankov 2004, p. 24

- Yankov 2004, p. 28

- Yankov 2004, pp. 27–28

- Yankov 2004, p. 30

- Yankov 2004, p. 21

- Yankov 2004, p. 22

- Yankov 2004, p. 23

- Yankov 2004, p. 32

- Yankov 2004, p. 33

- Yankov 2004, pp. 33–35

- Yankov 2004, pp. 35–36

- Yankov 2004, p. 43

- "Forests of Rila oak (Quercus protoroburoides)". Red Book of Bulgaria, Volume III. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Yankov 2004, p. 44

- Yankov 2004, pp. 44–45

- Yankov 2004, p. 57

- "Rila Monastery Nature Park: Flora". Trans-Border Network. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Yankov 2004, p. 58

- "Rila Monastery Nature Park, Protected Plants". Official Site of the Executive Forest Agency. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Yankov 2004, p. 59

- Yankov 2004, p. 52

- Yankov 2004, p. 53

- Yankov 2004, pp. 60–61

- Yankov 2004, p. 64

- Yankov 2004, p. 65

- Yankov 2004, p. 66

- Yankov 2004, p. 71

- "Rila Monastery Nature Park: Fauna". Trans-Border Network. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Yankov 2004, pp. 73–74

- Yankov 2004, p. 74

- Yankov 2004, p. 73

- Yankov 2004, p. 72

- Yankov 2004, p. 77

- Yankov 2004, p. 78

- Yankov 2004, p. 67

- Yankov 2004, pp. 70–71

- "Rila Monastery Nature Park: Cultural Heritage". Trans-Border Network. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery". Official Site of UNESCO. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery: History and General Information". Official Site of the Rila Monastery. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery: Architecture". Official Site of the Rila Monastery. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery: Museum". Official Site of the Rila Monastery. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- Yankov 2004, p. 95

- Yankov 2004, p. 107

- Yankov 2004, pp. 95–96

- Yankov 2004, p. 97

- Yankov 2004, p. 98

Sources

References

- Yankov (Янков), Petar (Петър) (2004). Rila Monastery Nature Park. Management Plan 2004–2013 (Природен парк "Рилски манастир". План за управление 2004–2013) (PDF) (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Ministry of Environment and Water.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rila Monastery Nature Park. |

- "Official Site of the Ministry of Environment and Water of Bulgaria". Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery Nature Park" (in Bulgarian). Official Site of Rila Monastery Nature Park. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery Nature Park" (in Bulgarian). Cross-Border Network: Nature for People and People for Nature. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery Nature Park" (in Bulgarian). Forest Agency to the Ministry of Environment and Water. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Rila Monastery". Official Site of Rila Monastery. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

_-_panoramio_(4).jpg)