Poplar admiral

The poplar admiral (Limenitis populi) is a butterfly in the subfamily Limenitinae of the family Nymphalidae.

| Poplar admiral | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Nymphalidae |

| Genus: | Limenitis |

| Species: | L. populi |

| Binomial name | |

| Limenitis populi | |

Habitat

Poplar admiral is widespread in continental Europe and across the Palearctic to Japan. The large, seldom-seen poplar admiral is one of the biggest butterflies in Europe. It is found in deciduous forests, where aspen (Populus tremula) or black poplar (Populus nigra) trees grow. This is because the caterpillar only eats the leaves of these species. At altitude, for instance in the Alps, where there are not large Populus forests, they accommodate with a grove, in the southeast of France they can be seen flying in large open spaces, for instance in the department of Alpes-Maritimes, as noted by Jacques Rigout.[1] The males are easier to find. The females are rarer, because they tend to stay in the tops of the trees and seldom venture to the ground.

Characteristics

The wingspan in spread specimens varies for the males from 72 to 80 mm, and for the females from 82 to 96 mm, all measures done on the larger private collection of Limenitis populi, now in the hands of Jean-Claude Weiss, a specialist of Parnassius. In fact, specimens in the field are relatively of the same size; the differences are mainly because of variations among subspecies, not variations at one location. There are some specimens that are very small, about half the usual size, but they have been specifically bred. There is a noticeable difference in size between sexes. The females have distinct broad white lines over their back wings. On the males the lines are narrower and fainter, and sometimes are not there at all. The upper surface is dark brown with white spots. The white stripe is surrounded by orange and blue borders. The underside is orange. Seitz - L. populi L. (56d). male. upperside black-brown, forewing with indistinct cell-spot, a curved row of discal spots and a straight row in the marginal area, all white or whitish: besides with a feeble brownish spot at the cellend and a double row of submarginal spots, of which the anterior ones are reddish, while the others are bluish or grey. Hindwing with a narrow whitish median band, a row of red-brown lunules in the marginal area and a double row of bluish spots at the margin. Underside for the most part light red-brown, with the markings of the upperside repeated in a grey-greenish tint, the margin of both wings greenish grey with a black undulate line, and near it two rows of black spots, which are less developed on the forevsing; basal and abdominal areas of the hindwing more or less grey-green, there being some black transverse bars in the anterior half of the basal area. The female larger, the spots of the forewing considerably wider, purer white, the median band of the hindwing much broader, transsected by the dark veins, the markings near the margin more prominent, glossy metallic green; the median band varies from greenish white to yellowish, being in some cases even deep yellow (Spuler).[2]

_Dos.jpg) Dorsal side – MHNT

Dorsal side – MHNT_Ventre.jpg) Ventral side – MHNT

Ventral side – MHNT Side view – MHNT

Side view – MHNT With opened wings

With opened wings

Behavior

They are attracted to foul smells, such as those given off by carrion or dung. The butterflies use their proboscis to draw important minerals from the sap of trees, from the ground or from sweat. They do not visit flowers.

Metamorphosis

The butterflies feed on aspens, and occasionally also black poplars in warm, wind-free locations. It is there that they lay their green eggs on the top side of the leaves.

Egg

Many errors in the literature still persist, such as Eugen Niculescu who described the egg as having ribs.[3] In fact, the egg is covered with hollow polygons.[4] The duration of the egg stage is 7 days, not 14 as E. Niculescu writes (l.c.).[5]

Caterpillar

Georg Dorfmeister was the first to describe and measure the caterpillar and chrysalid.[6]

Ekkehard Friedrich clearly described the early stages of the young larva.[7]

In Europe, the caterpillars feed on Populus tremula and P. nigra (not on P. alba). In Japan, they eat Populus maximowiczii (Tabuchi), and the Japanese subspecies even accept many varieties of willow (Salix sp.) in captivity.[8] In August the caterpillars, which are still quite small, make a cocoon from a leaf that they cut out and roll up. They spend the winter in this cocoon and then emerge from it before the leaves come out in the spring.

The green caterpillar has black and brown shades. Its head is reddish brown, and its sides are black. First it eats the leaf buds, then the new leaves. Pupation takes place in June in a leaf that is lightly spun together.

Adult

As a general rule, hatching occurs from the third week of June to mid-July, although some have been known to leave as early as May (which is often the case in Japan). In France the record dates of the flight period is from 30 May (in 1971) to 16 August (in 1974).

Male are seen first; the females stay at the top of the trees and are sometimes found on the ground about two weeks later, only in the morning, often when the males are no longer seen. Male flight can be very fast, the female flight is quite slow, somewhat like a glider.

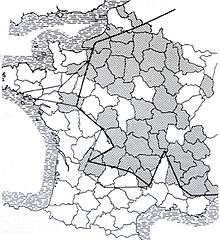

Distribution

The species is known to occur in western Europe from Denmark to northern Italy (the Spanish record noted by Miguel-Angel Gomez Bustillo[9] is doubtful), then Germany to Greece, Russia to Japan including China. Jacques Rigout has published precise distribution maps in France of this butterfly.[10] The study was done by listing the data from the specimens preserved in the Paris Museum and the British Museum and captures done by the French entomologists.

Conservation

The now rare poplar admiral is a protected species. The species is endangered primarily due to the clearing of forests containing the trees that they must feed on to survive, and replacement with more economically valuable conifer forests.

Subspecies

- Limenitis populi populi (Linnaeus), 1758[11] (Denmark, was described from Sweden but no longer exists there)

- Limenitis populi batangensis Huang, 2001[12] (Sichuan)

- Limenitis populi bucovinensis Hormuzaki, 1897[13] (Altai) (some authors say it is a good species: Limenitis bucovinensis Hormuzaki)

- Limenitis populi enapius Fruhstorfer, 1908[14] (= eunemius Fruhstorfer, 1908, l.c.) (Siberia, Mongolia)

- Limenitis populi fruhstorferi Krulikowsky, 1909[15] (Urals, West Siberia)

- Limenitis populi halasiensis Huang & Murayama, 1992[16] (Xinjiang)

- Limenitis populi jezoensis Matsumura, 1919[17] (Japan)

- Limenitis populi rilocola Stichel, 1908[18]- not Mitis - (South Europe, Greece)

- Limenitis populi szechwanica Murayama, 1981[19] (China)

- Limenitis populi tremulae Esper, 1798[20] with the forms belgiensis Cabeau, 1914[21] or diluta Spuler (most of Europe)

- Limenitis populi ussuriensis Staudinger, 1887[22] (= liliputana Staudinger, 1887, l.c.) (Ussuri, Korea?)

Other names are for aberrations:

- defasciata Schutz, 1908[23] without the white bands at the hindwings.

- excelsior Reiss[24] with the white bands very large.

- monochroma Mitis, 1891[25] with the upper face black with a shade of green.

- nigra Paux, 1901[26] (= monochroma Gilmer, 1909[27] (not Stichel) with the upper face entirely black.

- radiata Schutz, 1912[28] (not Fruhstofer, 1915) with the upper face black except two white spots.

- ruberrima Schutz, 1912[29] much more tawny.

References

- Rigout J. (1969). Observations et captures intéressantes (Nymphalidae, Papilionidae), Alexanor 6(4):174-176

- Seitz. A. in Seitz, A. ed. Band 1: Abt. 1, Die Großschmetterlinge des palaearktischen Faunengebietes, Die palaearktischen Tagfalter, 1909, 379 Seiten, mit 89 kolorierten Tafeln (3470 Figuren)

- Niculescu E. (1965). Fauna republicii populare Romîne. Nymphalidae, p. 116

- Tabuchi Y. (1959). The Alpine Butterflies of Japan.

- Friedrich E. (1986). Breeding Butterflies and Moths. Harley Books.

- Dorfmeister G. (1854). Zur Lebensart der Raupe der Limenitis populi O., Verhandlungen der Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien 4:483-486, and a plate

- Friedrich E. (1971). Zur Biologie von Limenitis populi L. (Lep., Nymphalidae), Entomologische Zeitschrift, 81(23):266-269.

- Friedrich E. (1975). Salix-Arten als futterpflanze von Limenitis populi; weitere Bemerkungen zur Biologie des Falters, Entomologische Zeitschrift 85:164-167

- Gomez Bustillo M.-A. (1974). Mariposas de la Peninsula Iberica. Vol. 1 & 2. Ropaloceros

- Rigout J. (1976). Répartition de Limenitis populi en France, Bulletin de la Société Sciences Nat, 10

- Linnaeus C. Systema Naturae… (ed. 10), 1:476.

- Huang H. (2001). Neue Entomologische Nachrichten 51:88.

- Hormuzaki C. (1897). Die Schmetterlinge (Lepidoptera) der Bukowina. I. Theil. - Verhandlungen der k. k. zoologisch-botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien 47.

- Fruhstorfer H. (1908). Internazionale Entomologische Zeitschrift 2(8):50

- Krulikowsky L. (1909). Revue Russe d'Entomologie 9:111.

- Huang H. & Murayama S. (1992). Tyô to Ga 43:9.

- Matsumura S. (1919). Thousand insects of Japan, Tokyo Additamenta 3.

- Stichel S. (1908). in Seitz: Die Gross-Schmetterlinge der Erde. Vol. 1.

- Murayama S. 1981). Notes on some butterflies of Provinces Szechwan, Zhejiang, Taiwan in China. New Entomol. 30:10-13.

- Esper E. (1798). Die ausländischen oder die ausserhalb Europa zur Zeit in den übrigen Welttheilen vorgefundenen Schmetterlinge in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschribungen 1.

- Cabeau C. (1914). Revue de la Société Entomologique Namuroise 14:23.

- Staudinger O. (1887). Mémoires sur les Lépidoptères 3:143.

- Schutz O. (1908). Abart von Limenitis populi L., Societas Entomologica 22(24):188.

- Reiß H. (1942). Interessante Tagfalteraberrationen aus Württemberg, Entomologische Zeitschrift 55(34):266-268.

- Mitis H. von. (1891). Jahresb. Wien. Ent. Ver 17:114.

- Paux P. (1901). Les Lépidoptères du Département du Nord

- Gilmer W. (1909). Jahreshefte des Vereins für schlesische Insekten-kunde zu Breslau, Heft 2:37.

- Schutz O. (1912). Entomologische Zeitschrift Guben 17:61.

- Schutz O. (1912). Entomologische Zeitschrift Guben 17:62.