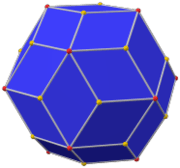

Rhombic triacontahedron

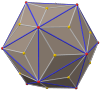

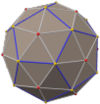

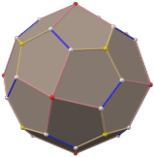

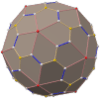

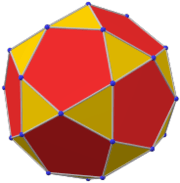

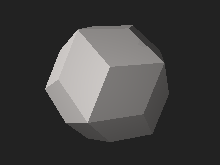

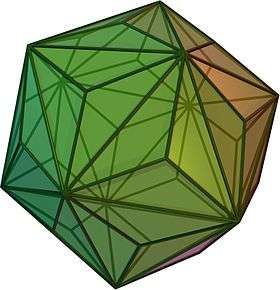

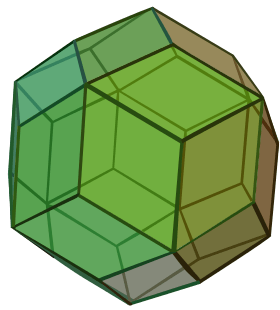

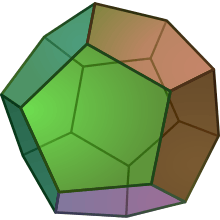

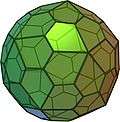

In geometry, the rhombic triacontahedron, sometimes simply called the triacontahedron as it is the most common thirty-faced polyhedron, is a convex polyhedron with 30 rhombic faces. It has 60 edges and 32 vertices of two types. It is a Catalan solid, and the dual polyhedron of the icosidodecahedron. It is a zonohedron.

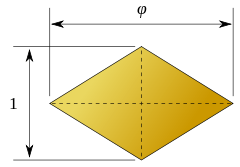

A face of the rhombic triacontahedron. The lengths of the diagonals are in the golden ratio. |

| Rhombic triacontahedron | |

|---|---|

(Click here for rotating model) | |

| Type | Catalan solid |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Conway notation | jD |

| Face type | V3.5.3.5 rhombus |

| Faces | 30 |

| Edges | 60 |

| Vertices | 32 |

| Vertices by type | 20{3}+12{5} |

| Symmetry group | Ih, H3, [5,3], (*532) |

| Rotation group | I, [5,3]+, (532) |

| Dihedral angle | 144° |

| Properties | convex, face-transitive isohedral, isotoxal, zonohedron |

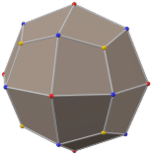

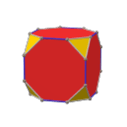

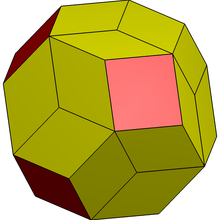

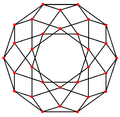

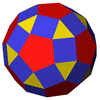

Icosidodecahedron (dual polyhedron) |

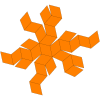

Net |

The ratio of the long diagonal to the short diagonal of each face is exactly equal to the golden ratio, φ, so that the acute angles on each face measure 2 tan−1(1/φ) = tan−1(2), or approximately 63.43°. A rhombus so obtained is called a golden rhombus.

Being the dual of an Archimedean solid, the rhombic triacontahedron is face-transitive, meaning the symmetry group of the solid acts transitively on the set of faces. This means that for any two faces, A and B, there is a rotation or reflection of the solid that leaves it occupying the same region of space while moving face A to face B.

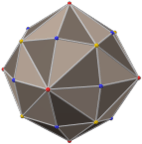

The rhombic triacontahedron is somewhat special in being one of the nine edge-transitive convex polyhedra, the others being the five Platonic solids, the cuboctahedron, the icosidodecahedron, and the rhombic dodecahedron.

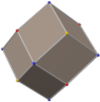

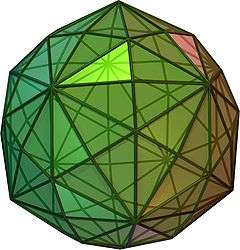

The rhombic triacontahedron is also interesting in that its vertices include the arrangement of four Platonic solids. It contains ten tetrahedra, five cubes, an icosahedron and a dodecahedron. The centers of the faces contain five octahedra.

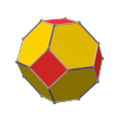

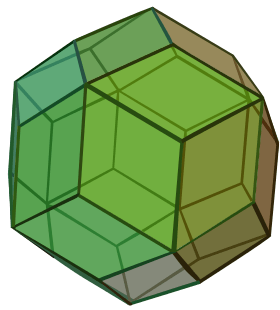

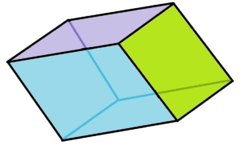

It can be made from a truncated octahedron by dividing the hexagonal faces into 3 rhombi:

Cartesian coordinates

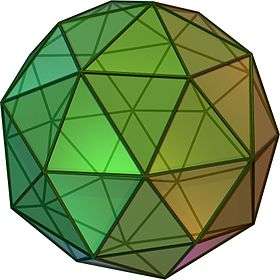

Let be the golden ratio. The 12 points given by and cyclic permutations of these coordinates are the vertices of a regular icosahedron. Its dual regular dodecahedron, whose edges intersect those of the icosahedron at right angles, has as vertices the 8 points together with the 12 points and cyclic permutations of these coordinates. All 32 points together are the vertices of a rhombic triacontahedron centered at the origin. The length of its edges is . Its faces have diagonals with lengths and .

Dimensions

If the edge length of a rhombic triacontahedron is a, surface area, volume, the radius of an inscribed sphere (tangent to each of the rhombic triacontahedron's faces) and midradius, which touches the middle of each edge are:[1]

where φ is the golden ratio.

The insphere is tangent to the faces at their face centroids. Short diagonals belong only to the edges of the inscribed regular dodecahedron, while long diagonals are included only in edges of the inscribed icosahedron.

Dissection

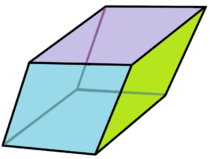

The rhombic triacontahedron can be dissected into 20 golden rhombohedra: 10 acute ones and 10 obtuse ones.[2][3]

| 10 | 10 |

|---|---|

Acute form |

Obtuse form |

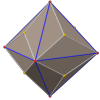

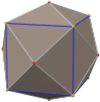

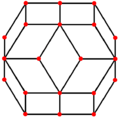

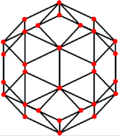

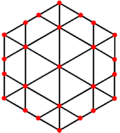

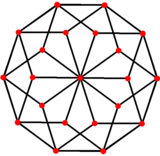

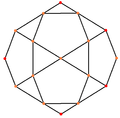

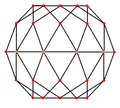

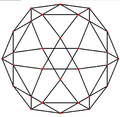

Orthogonal projections

The rhombic triacontahedron has four symmetry positions, two centered on vertices, one mid-face, and one mid-edge. Embedded in projection "10" are the "fat" rhombus and "skinny" rhombus which tile together to produce the non-periodic tessellation often referred to as Penrose tiling.

| Projective symmetry |

[2] | [2] | [6] | [10] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image |  |

|

|

|

| Dual image |

|

|

|

|

Stellations

The rhombic triacontahedron has 227 fully supported stellations.[4][5] Another stellation of the Rhombic triacontahedron is the compound of five octahedra. The total number of stellations of the rhombic triacontahedron is 358,833,097.

Related polyhedra

| Family of uniform icosahedral polyhedra | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [5,3], (*532) | [5,3]+, (532) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| {5,3} | t{5,3} | r{5,3} | t{3,5} | {3,5} | rr{5,3} | tr{5,3} | sr{5,3} |

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

| V5.5.5 | V3.10.10 | V3.5.3.5 | V5.6.6 | V3.3.3.3.3 | V3.4.5.4 | V4.6.10 | V3.3.3.3.5 |

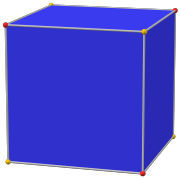

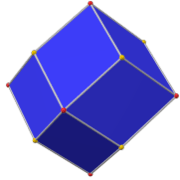

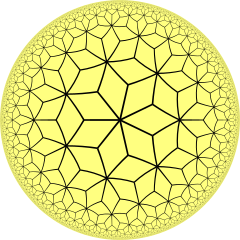

This polyhedron is a part of a sequence of rhombic polyhedra and tilings with [n,3] Coxeter group symmetry. The cube can be seen as a rhombic hexahedron where the rhombi are also rectangles.

| Symmetry mutations of dual quasiregular tilings: V(3.n)2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *n32 | Spherical | Euclidean | Hyperbolic | ||||||||

| *332 | *432 | *532 | *632 | *732 | *832... | *∞32 | |||||

| Tiling |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| Conf. | V(3.3)2 | V(3.4)2 | V(3.5)2 | V(3.6)2 | V(3.7)2 | V(3.8)2 | V(3.∞)2 | ||||

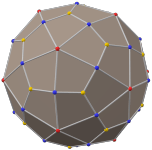

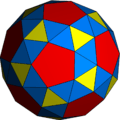

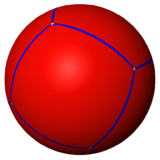

Spherical rhombic triacontahedron

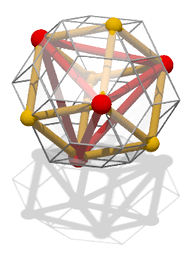

Spherical rhombic triacontahedron A rhombic triacontahedron with an inscribed tetrahedron (red) and cube (yellow).

A rhombic triacontahedron with an inscribed tetrahedron (red) and cube (yellow).

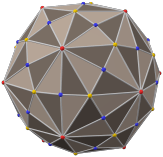

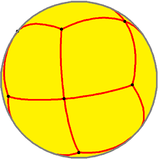

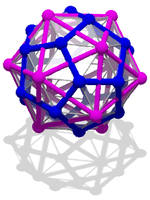

(Click here for rotating model) A rhombic triacontahedron with an inscribed dodecahedron (blue) and icosahedron (purple).

A rhombic triacontahedron with an inscribed dodecahedron (blue) and icosahedron (purple).

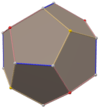

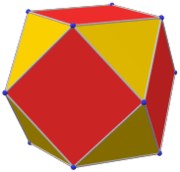

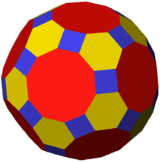

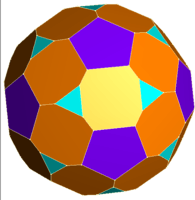

(Click here for rotating model) Fully truncated rhombic triacontahedron

Fully truncated rhombic triacontahedron

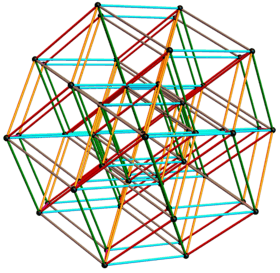

6-cube

The rhombic triacontahedron forms a 32 vertex convex hull of one projection of a 6-cube to three dimensions.

The 3D basis vectors [u,v,w] are:

|

Shown with inner edges hidden 20 of 32 interior vertices form a dodecahedron, and the remaining 12 form an icosahedron. |

Uses

Danish designer Holger Strøm used the rhombic triacontahedron as a basis for the design of his buildable lamp IQ-light (IQ for "Interlocking Quadrilaterals").

Woodworker Jane Kostick builds boxes in the shape of a rhombic triacontahedron.[6] The simple construction is based on the less than obvious relationship between the rhombic triacontahedron and the cube.

Roger von Oech's "Ball of Whacks" comes in the shape of a rhombic triacontahedron.

The rhombic triacontahedron is used as the "d30" thirty-sided die, sometimes useful in some roleplaying games or other places.

Christopher Bird, co-author of The Secret Life of Plants wrote an article for New Age Journal in May, 1975, popularizing the dual icosahedron and dodecahedron as "the crystalline structure of the Earth," a model of the "Earth (telluric) energy Grid." The EarthStar Globe by Bill Becker and Bethe A. Hagens purports to show "the natural geometry of the Earth, and the geometric relationship between sacred places such as the Great Pyramid, the Bermuda Triangle, and Easter Island." It is printed as a rhombic triacontahedron, on 30 diamonds, and folds up into a globe.[7]

See also

- Golden rhombus

- Rhombille tiling

- Truncated rhombic triacontahedron

References

- Stephen Wolfram, "" from Wolfram Alpha. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Dissection of the rhombic triacontahedron

- Pawley, G. S. (1975). "The 227 triacontahedra". Geometriae Dedicata. Kluwer Academic Publishers. 4 (2–4): 221–232. doi:10.1007/BF00148756. ISSN 1572-9168.

- Messer, P. W. (1995). "Stellations of the Rhombic Triacontahedron and Beyond". Structural Topology. 21: 25–46.

- triacontahedron box - KO Sticks LLC

- http://www.vortexmaps.com/grid-history.php

- Williams, Robert (1979). The Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure: A Source Book of Design. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-23729-X. (Section 3-9)

- Wenninger, Magnus (1983), Dual Models, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511569371, ISBN 978-0-521-54325-5, MR 0730208 (The thirteen semiregular convex polyhedra and their duals, p. 22, Rhombic triacontahedron)

- The Symmetries of Things 2008, John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strass, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 21, Naming the Archimedean and Catalan polyhedra and tilings, p. 285, Rhombic triacontahedron )

External links

- Eric W. Weisstein, Rhombic triacontahedron (Catalan solid) at MathWorld.

- Rhombic Triacontrahedron – Interactive Polyhedron Model

- Virtual Reality Polyhedra – The Encyclopedia of Polyhedra

- Stellations of Rhombic Triacontahedron

- EarthStar globe – Rhombic Triacontahedral map projection

- IQ-light—Danish designer Holger Strøm's lamp

- Make your own

- a wooden construction of a rhombic triacontahedron box – by woodworker Jane Kostick

- 120 Rhombic Triacontahedra, 30+12 Rhombic Triacontahedra, and 12 Rhombic Triacontahedra by Sándor Kabai, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project

- A viper drawn on a rhombic triacontahedron.