Regional integration

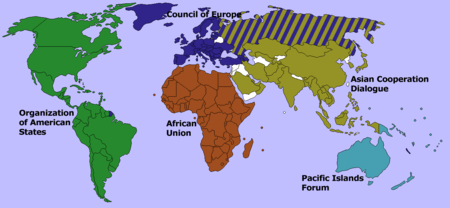

Regional Integration is a process in which neighboring states enter into an agreement in order to upgrade cooperation through common institutions and rules. The objectives of the agreement could range from economic to political to environmental, although it has typically taken the form of a political economy initiative where commercial interests are the focus for achieving broader socio-political and security objectives, as defined by national governments. Regional integration has been organized either via supranational institutional structures or through intergovernmental decision-making, or a combination of both.

.png)

Past efforts at regional integration have often focused on removing barriers to free trade in the region, increasing the free movement of people, labour, goods, and capital across national borders, reducing the possibility of regional armed conflict (for example, through Confidence and Security-Building Measures), and adopting cohesive regional stances on policy issues, such as the environment, climate change and migration.

Intra-regional trade refers to trade which focuses on economic exchange primarily between countries of the same region or economic zone. In recent years countries within economic-trade regimes such as ASEAN in Southeast Asia for example have increased the level of trade and commodity exchange between themselves which reduces the inflation and tariff barriers associated with foreign markets resulting in growing prosperity.

Overview

Regional integration has been defined as the process through which independent national states "voluntarily mingle, merge and mix with their neighbors so as to lose the factual attributes of sovereignty while acquiring new techniques for resolving conflicts among themselves."[1] De Lombaerde and Van Langenhove describe it as a worldwide phenomenon of territorial systems that increases the interactions between their components and creates new forms of organization, co-existing with traditional forms of state-led organization at the national level.[2] Some scholars see regional integration simply as the process by which states within a particular region increase their level interaction with regard to economic, security, political, or social and cultural issues.[3]

In short, regional integration is the joining of individual states within a region into a larger whole. The degree of integration depends upon the willingness and commitment of independent sovereign states to share their sovereignty. The deep integration that focuses on regulating the business environment in a more general sense is faced with many difficulties.[4]

Regional integration initiatives, according to Van Langenhove, should fulfill at least eight important functions:

- the strengthening of trade integration in the region

- the creation of an appropriate enabling environment for private sector development

- the development of infrastructure programmes in support of economic growth and regional integration

- the development of strong public sector institutions and good governance;

- the reduction of social exclusion and the development of an inclusive civil society

- contribution to peace and security in the region

- the building of environment programmes at the regional level

- the strengthening of the region’s interaction with other regions of the world.[5]

The crisis of the post-war order led to the emergence of a new global political structure. This new global political structure made obsolete the classical Westphalian concept of a system of sovereign states to conceptualize world politics. The concept of sovereignty became looser and the old legal definitions of the ultimate and fully autonomous power of a nation-state are no longer meaningful. Sovereignty, which gained meaning as an affirmation of cultural identity, has lost meaning as power over the economy. All regional integration projects during the Cold War were built on the Westphalian state system and were designed to serve economic growth as well as security motives in their assistance to state building goals. Regional integration and globalization are two phenomena that have challenged the pre-existing global order based upon sovereign states since the beginning of the twenty-first century. The two processes deeply affect the stability of the Westphalian state system, thus contributing to both disorder and a new global order.

Closer integration of neighbouring economies has often been seen by governments as a first step in creating a larger regional market for trade and investment. This is claimed to spur greater efficiency, productivity gain and competitiveness, not just by lowering border barriers, but by reducing other costs and risks of trade and investment. Bilateral and sub-regional trading arrangements have been advocated by governments as economic development tools, as they been designed to promote economic deregulation. Such agreements have also aimed to reduce the risk of reversion towards protectionism, locking in reforms already made and encouraging further structural adjustment.

Some claim the desire for closer integration is usually related to a larger desire for opening nation states to the outside world, or that regional economic cooperation is pursued as a means of promoting development through greater efficiency, rather than as a means of disadvantaging others. It is also claimed that the members of these arrangements hope that they will succeed as building blocks for progress with a growing range of partners and towards a generally freer and open global environment for trade and investment and that integration is not an end in itself, but a process to support economic growth strategies, greater social equality and democratisation.[6] However, regional integration strategies as pursued by economic and national interests, particularly in the last 30 years, have also been highly contested across civil society. There is no conclusive evidence to suggest that the strategies of economic deregulation or increased investor protection implemented as forms of regional integration have succeeded in contributing to "progress" in sustainable economic growth, as the number of economic crises around the world has increased in frequency and intensity over the past decades. Also, there is increasing evidence that the forms of regional integration employed by nation states have actually worsened social inequality and diminished democratic accountability. As a result of the persisting contradiction between the old promises of regional integration and real-world experience, the demand from across global civil society for alternative forms of regional integration has grown.[7]

Regional integration arrangements are a part and parcel of the present global economic order and this trend is now an acknowledged future of the international scene. It has achieved a new meaning and new significance. Regional integration arrangements are mainly the outcome of necessity felt by nation-states to integrate their economies in order to achieve rapid economic development, decrease conflict, and build mutual trusts between the integrated units. The nation-state system, which has been the predominant pattern of international relations since the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 is evolving towards a system in which regional groupings of states is becoming increasingly important vis-a-vis sovereign states. Some have argued that the idea of the state and its sovereignty has been made irrelevant by processes that are taking place at both the global and local level. Walter Lippmann believes that "the true constituent members of the international order of the future are communities of states."[8] E.H. Carr shares Lippmann view about the rise of regionalism and regional arrangements and commented that "the concept of sovereignty is likely to become in the future even more blurred and indistinct than it is at present."[9]

Regional integration agreements

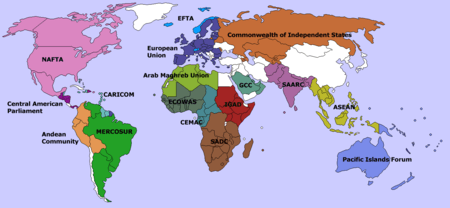

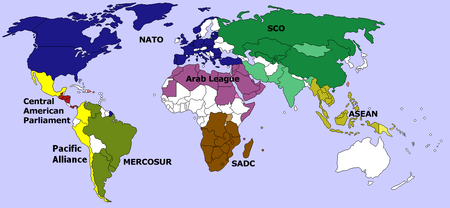

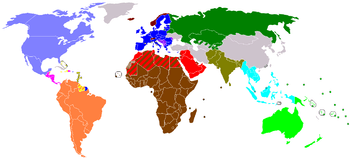

Regional integration agreements (RIAs) have led to major developments in international relations between and among many countries, specifically increases in international trade and investment and in the formation of regional trading blocs. As fundamental to the multi-faceted process of globalization, regional integration has been a major development in the international relations of recent years. As such, Regional Integration Agreements has gained high importance. Not only are almost all the industrial nations part of such agreements, but also a huge number of developing nations too are a part of at least one, and in cases, more than one such agreement.

The amount of trade that takes place within the scope of such agreements is about 35%, which accounts to more than one-third of the trade in the world. The main objective of these agreements is to reduce trade barriers among those nations concerned, but the structure may vary from one agreement to another. The removal of the trade barriers or liberalization of many economies has had multiple impacts, in some cases increasing Gross domestic product (GDP), but also resulting in greater global inequality, concentration of wealth and an increasing frequency and intensity of economic crises.

The number of agreements agreed under the rules of the GATT and the WTO and signed in each year has dramatically increased since the 1990s. There were 194 agreements ratified in 1999 and it contained 94 agreements form the early 1990s.[10]

The last few years have experienced huge qualitative as well as quantitative changes in the agreements related to the Regional Integration Scheme. The top three major changes were the following:

- Deep Integration Recognition

- Closed regionalism to open model

- Advent of trade blocs

Deep Integration Recognition

Deep Integration Recognition analyses the aspect that effective integration is a much broader aspect, surpassing the idea that reducing tariffs, quotas and barriers will provide effective solutions. Rather, it recognizes the concept that additional barriers tend to segment the markets. That impedes the free flow of goods and services, along with ideas and investments. Hence, it is now recognized that the current framework of traditional trade policies are not adequate enough to tackle these barriers. Such deep-integration was first implemented in the Single Market Program in the European Union. However, in the light of the modern context, that debate is being propounded into the clauses of different regional integration agreements arising out of increase in international trade.[10] (EU).

Closed regionalism to open model

The change from a system of closed regionalism to a more open model had arisen out of the fact that the section of trading blocs that were created among the developing countries during the 1960s and 1970s were based on certain specific models such as those of import substitution as well as regional agreements coupled with the prevalence generally high external trade barriers. The positive aspects of such shifting is that there has been some restructuring of certain old agreements. The agreements tend to be more forward in their outward approach as well as show commitment in trying to advance international trade and commerce instead to trying to put a cap on it by way of strict control.[10]

Trade blocks

The Advent of Trade Blocks tend to draw in some parity between high-income industrial countries and developing countries with a much lower income base in that they tend to serve as equal partners under such a system. The concept of equal partners grew out of the concept of providing reinforcement to the economies to all the member countries. The various countries then agree upon the fact that they will help economies to maintain the balance of trade between and prohibit the entry of other countries in their trade process.

An important example would be the North American Free Trade Area, formed in 1994 when the Canada - US Free Trade Agreement was extended to Mexico. Another vibrant example would entail as to how EU has formed linkages incorporating the transition economies of Eastern Europe through the Europe Agreements. It has signed agreements with the majority of Mediterranean countries by highly developing the EU-Turkey customs union and a Mediterranean policy.[10] Vysegrád four is a group of states co-operating in order to achieve higher economic results[11]

Recent regional integration

Regional integration in Europe was consolidated in the Treaty on the European Union (the Maastricht Treaty), which came into force in November 1993 and established the European Union. The European Free Trade Association is a free trade bloc of four countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Switzerland and Norway) which operates in parallel and is linked to the European Union. In January 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement was formed when Mexico acceded to a prior-existing bilateral free trade agreement between the US and Canada. In The Pacific there was the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) in 1993 which looked into reducing the tariffs. The AFTA started in full swing in 2000.

Alternative Regional Integration

In the last decade regional integration has accelerated and deepened around the world, in Latin America and North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia, with the formation of new alliances and trading blocks. However, critics of the forms this integration has taken have consistently pointed out that the forms of regional integration promoted have often been neoliberal in character, in line with the motives and values of the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank - promoting financial deregulation, the removal of barriers to capital and global corporations, their owners and investors; focusing on industrialisation, boosting global trade volumes and increasing GDP. This has been accompanied by a stark increase in global inequality, growing environmental problems as a result of industrial development, the displacement of formerly rural communities, ever-expanding urban slums, rising unemployment and the dismantling of social and environmental protections. Global financial deregulation has also contributed to the increasing frequency and severity of economic crises, while Governments have increasingly lost the sovereignty to take action to protect and foster weakened economies, as they are held to the rules of free trade implemented by the WTO and IMF.

Advocates of alternative regional integration argue strongly that the solutions to global crises (financial, economic, environmental, climate, energy, health, food, social, etc.) must involve regional solutions and regional integration, since they transcend national borders and territories, and require the cooperation of different peoples across geography. However, they propose alternatives to the dominant forms of neoliberal integration, which attends primarily to the needs of transnational corporations and investors. Renowned economist, Harvard professor, former senior vice president and chief economist of the World Bank, Joseph Stiglitz has also argued strongly against neoliberal globalisation (see Neoliberalism). Stiglitz argues that the deregulation, free trade, and social spending cuts or austerity policies of neoliberal economics have actually created and worsened global crises. In his 2002 book Globalization and Its Discontents he explains how the industrialized economies of the US, Europe, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan developed not with the neoliberal policies promoted in developing countries and the global South by the WTO, IMF and World Bank, but rather with a careful mix of protection, regulation, social support and intervention from national governments in the market.

The People’s Agenda for Alternative Regionalisms

The People’s Agenda for Alternative Regionalisms [12] is a network of civil society, social movement and community-based organisations from around the world, calling for alternative forms of regional integration. PAAR strives to "promote cross-fertilisation of experiences on regional alternatives among social movements and civil society organisations from Asia, Africa, South America and Europe." Further "[i]t aims to contribute to the understanding of alternative regional integration as a key strategy to struggle against neoliberal globalisation and to broaden the base among key social actors for political debate and action around regional integration" and is thus committed to expanding and deepening global democracy.

PAAR aims to "build trans-regional processes to develop the concept of “people’s integration”, articulate the development of new analyses and insights on key regional issues, expose the problems of neoliberal regional integration and the limits of the export-led integration model, share and develop joint tactics and strategies for critical engagement with regional integration processes as well as the development of people’s alternatives." It draws on and extends the work of such, Southern African People’s Solidarity Network- SAPSN (Southern Africa).

The PAAR initiative aims to develop these networks and support their efforts to reclaim democracy in the regions, recreate processes of regional integration and advance people-centred regional alternatives. In the video Global Crises, Regional Solutions the network argues that regional integration and cooperation is essential for tackling the many dimensions of the current global crises and that no country can face these crises alone. The video also calls for countries to break their dependency on the global markets, as well as the dominant development model that has failed to address increasing global hunger, poverty and environmental destruction, resulting instead in greater inequality and social unrest. Regional integration, the video argues, should be much more than macro-economic cooperation between states and corporations; it should protect shared ecological resources and should promote human development - health, wellbeing and democracy - as the base of economic development.

See also

- Free trade area

- Globalization

- European integration

References

- Haas, Ernst B. (1971) ‘The Study of Regional Integration: Reflections on the Joy and Anguish of Pretheorizing’, pp. 3-44 in Leon N. Lindberg and Stuart A. Scheingold (eds.), Regional Integration: Theory and Research. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- De Lombaerde, P. and Van Langenhove, L: "Regional Integration, Poverty and Social Policy." Global Social Policy 7 (3): 377-383, 2007.

- Van Ginkel, H. and Van Langenhove, L: "Introduction and Context" in Hans van Ginkel, Julius Court and Luk Van Langenhove (Eds.), Integrating Africa: Perspectives on Regional Integration and Development, UNU Press, 1-9, 2003.

- Claar, Simone and Noelke Andreas (2010), Deep Integration. In: D+C, 2010/03, 114-117.

- De Lombaerde and Van Langenhove 2007, pp. 377-383.

- Thongkholal Haokip (2012), "Recent Trends in Regional Integration and the Indian Experience", International Area Studies Review, Vol. 15, No. 4, December 2012, pp. 377-392.

- People's Agenda for Alternative Regionalisms. "About PAAR. What is the Initiative People’s Agenda for Alternative Regionalisms?

- Source Needed

- Carr, E.H. The Twenty Years Crisis, 1919-1939. Macmillan, 1978: 230-231.

- "RIA" (PDF).

- Kft., Webra International (2011-03-21). "The Visegrad Group: the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia | News". www.visegradgroup.eu. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- http://www.alternative-regionalisms.org/?page_id=2

Bibliography

- Bösl, Anton, Breytenbach, Willie, Hartzenberg, Trudi, McCarthy, Colin, Schade, Klaus (Eds), Monitoring Regional Integration in Southern Africa, Yearbook Vol 8 (2008), Stellenbosch 2009. ISBN 978-0-9814221-2-1

- Claar, Simone and Noelke Andreas (2010), Deep Integration. In: D+C, 2010/03, 114-117.

- Duina, Francesco (2007). The Social Construction of Free Trade: The EU, NAFTA, and Mercosur. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Haas, Ernst B. (1964). Beyond the Nation State: Functionalism and International Organization. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0187-7

- Lindberg, Leon N., and Stuart A. Scheingold (eds.) (1971). Regional Integration: Theory and Research. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-75326-6

- Michael, Arndt (2013). India's Foreign Policy and Regional Multilateralism. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137263117.

- Nye, Joseph S. (1971). Peace in Parts. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 159089 OCLC 246008784