Robert Rauschenberg

Milton Ernest "Robert" Rauschenberg (October 22, 1925 – May 12, 2008) was an American painter and graphic artist whose early works anticipated the pop art movement. Rauschenberg is well known for his "combines" of the 1950s, in which non-traditional materials and objects were employed in various combinations. Rauschenberg was both a painter and a sculptor, and the combines are a combination of the two, but he also worked with photography, printmaking, papermaking and performance.[1][2]

Robert Rauschenberg | |

|---|---|

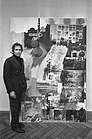

.jpg) Rauschenberg in 1968 | |

| Born | Milton Ernest Rauschenberg October 22, 1925 |

| Died | May 12, 2008 (aged 82) |

| Education | Kansas City Art Institute Académie Julian Black Mountain College Art Students League of New York |

| Known for | Assemblage |

Notable work | Canyon (1959) Monogram (1959) |

| Movement | Neo-Dada, Abstract Expressionism |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Awards | Leonardo da Vinci World Award of Arts (1995) Praemium Imperiale (1998) |

Rauschenberg was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1993[3] and the Leonardo da Vinci World Award of Arts in 1995 in recognition of his more than 40 years of artmaking.[4]

Rauschenberg lived and worked in New York City and on Captiva Island, Florida, until his death from heart failure on May 12, 2008.[5]

Life and career

Rauschenberg was born Milton Ernest Rauschenberg in Port Arthur, Texas, the son of Dora Carolina (née Matson) and Ernest R. Rauschenberg.[6][7][8] His father was of German and Cherokee and his mother of Anglo-Saxon ancestry.[9][10] His parents were Fundamentalist Christians.[9] Rauschenberg was dyslexic.[11] He had a younger sister named Janet Begneaud.

At 16, Rauschenberg was admitted to the University of Texas at Austin where he began studying pharmacology.[11] He was drafted into the United States Navy in 1944. Based in California, he served as a mental hospital technician until his discharge in 1945-1946.[11]

Rauschenberg subsequently studied at the Kansas City Art Institute and the Académie Julian in Paris[12], France, where he met the painter Susan Weil. In 1948 Rauschenberg and Weil decided to attend Black Mountain College in North Carolina.[13][14]

Josef Albers, a founder of the Bauhaus, became Rauschenberg's painting instructor at Black Mountain, something Rauschenberg had looked forward to. His hope was that Albers would curb the younger artist's congenital sloppiness.[15] Albers' preliminary courses relied on strict discipline that did not allow for any "uninfluenced experimentation".[16] Rauschenberg described Albers as influencing him to do "exactly the reverse" of what he was being taught.[5]

Rauschenberg became, in his own words, "Albers' dunce, the outstanding example of what he was not talking about".[17] He found a better suited mentor in John Cage, and after collaborations with the musician Rauschenberg moved forward to create his combines.[15]

From 1949 to 1952 Rauschenberg studied with Vaclav Vytlacil and Morris Kantor at the Art Students League of New York,[18] where he met fellow artists Knox Martin and Cy Twombly.[19]

Rauschenberg married Susan Weil in the summer of 1950 at the Weil family home in Outer Island, Connecticut. Their only child, Christopher, was born July 16, 1951. The two separated in June 1952 and divorced in 1953.[20] According to a 1987 oral history by the composer Morton Feldman, after the end of his marriage, Rauschenberg had romantic relationships with fellow artists Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns.[21] An article by Jonathan D. Katz states that Rauschenberg's affair with Twombly began during his marriage to Susan Weil.[22] His partner for the last 25 years of his life was artist Darryl Pottorf,[23] his former assistant.[18]

Death

Rauschenberg died on May 12, 2008, on Captiva Island, Florida,[24] of heart failure at the age of 82, after a personal decision to go off life support.[25][23]

Artistic contribution

Rauschenberg's approach was sometimes called "Neo Dadaist," a label he shared with the painter Jasper Johns.[26] Rauschenberg was quoted as saying that he wanted to work "in the gap between art and life" suggesting he questioned the distinction between art objects and everyday objects, reminiscent of the issues raised by the Fountain, by Dada pioneer, Marcel Duchamp.[27] At the same time, Johns' paintings of numerals, flags, and the like, were reprising Duchamp's message of the role of the observer in creating art's meaning.

Alternatively, in 1961, Rauschenberg took a step in what could be considered the opposite direction by championing the role of creator in creating art's meaning. Rauschenberg was invited to participate in an exhibition at the Galerie Iris Clert, where artists were to create and display a portrait of the owner, Iris Clert. Rauschenberg's submission consisted of a telegram sent to the gallery declaring "This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say so."

_(38668628735).jpg)

From the fall of 1952 to the spring of 1953 Rauschenberg traveled through Europe and North Africa with his fellow artist and partner Cy Twombly. In Morocco, he created collages and boxes out of trash. He took them back to Italy, where he was noted by the influential gallery owner Irene Brin[28], and exhibited them at galleries in Rome and Florence. A lot of them sold; those that did not he threw into the river Arno.[29] From his stay, 38 collages survived.[30] In a famously cited incident of 1953, Rauschenberg erased a drawing by de Kooning, which he obtained from his colleague for the express purpose of erasing it as an artistic statement. The result is titled Erased de Kooning Drawing.[31][32]

By 1962, Rauschenberg's paintings were beginning to incorporate not only found objects but found images as well - photographs transferred to the canvas by means of the silkscreen process. Previously used only in commercial applications, silkscreen allowed Rauschenberg to address the multiple reproducibility of images, and the consequent flattening of experience that implies. In this respect, his work is contemporaneous with that of Andy Warhol, and both Rauschenberg and Johns are frequently cited as important forerunners of American Pop Art.

In 1966, Billy Klüver and Rauschenberg officially launched Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) a non-profit organization established to promote collaborations between artists and engineers.[33]

In 1969, NASA invited Rauschenberg to witness the launch of Apollo 11. In response to this landmark event, Rauschenberg created his Stoned Moon Series of lithographs. This involved combining diagrams and other images from NASA's archives with photographs from various media outlets, as well as with his own work.[34][35]

From 1970 he worked from his home and studio in Captiva, Florida. His first project on Captiva Island was a 16.5-meter-long silkscreen print called Currents (1970), made with newspapers from the first two months of the year, followed by Cardboards (1970–71) and Early Egyptians (1973–74), the latter of which is a series of wall reliefs and sculptures constructed from used boxes. He also printed on textiles using his solvent-transfer technique to make the Hoarfrosts (1974–76) and Spreads (1975–82), and in the Jammers (1975–76), created a series of colorful silk wall and floor works. Urban Bourbons (1988–95) focused on different methods of transferring images onto a variety of reflective metals, such as steel and aluminum. In addition, throughout the 1990s, Rauschenberg continued to utilize new materials while still working with more rudimentary techniques, such as wet fresco, as in the Arcadian Retreat (1996) series, and the transfer of images by hand, as in the Anagrams (1995–2000). As part of his engagement with the latest technological innovations, he began making digital Iris prints and using biodegradable vegetable dyes in his transfer processes, underscoring his commitment to caring for the environment.[36]

The White Paintings, black paintings, and Red Paintings

In 1951 Rauschenberg created his White Painting series in the tradition of monochromatic painting established by Kazimir Malevich, who reduced painting to its most essential qualities for an experience of aesthetic purity and infinity.[37] The White Paintings were shown at Eleanor Ward's Stable Gallery in New York in fall 1953. Rauschenberg used everyday white house paint and paint rollers to create smooth, unembellished surfaces which at first appear as blank canvas. Instead of perceiving them to be without content, however, John Cage described the White Paintings as "airports for the lights, shadows and particles";[38] surfaces which reflected delicate atmospheric changes in the room. Rauschenberg himself said that they were affected by ambient conditions, "so you could almost tell how many people are in the room." Like the White Paintings, the black paintings of 1951-1953 were executed on multiple panels and were predominantly single color works. Rauschenberg applied matte and glossy black paint to textured grounds of newspaper on canvas, occasionally allowing the newspaper to remain visible.

By 1953 Rauschenberg had moved from the White Painting and black painting series to the heightened expressionism of his Red Painting series. He regarded red as "the most difficult color" with which to paint, and accepted the challenge by dripping, pasting, and squeezing layers of red pigment directly onto canvas grounds that included patterned fabric, newspaper, wood, and nails.[39] The complex material surfaces of the Red Paintings were forerunners of Rauschenberg's well-known Combine series (1954-1964).[37]

Combines

Rauschenberg collected discarded objects on the streets of New York City and brought them back to his studio where he integrated them into his work. He claimed he "wanted something other than what I could make myself and I wanted to use the surprise and the collectiveness and the generosity of finding surprises. [...] So the object itself was changed by its context and therefore it became a new thing."[32]

Rauschenberg's comment concerning the gap between art and life provides the departure point for an understanding of his contributions as an artist.[27] He saw the potential beauty in almost anything; he once said, "I really feel sorry for people who think things like soap dishes or mirrors or Coke bottles are ugly, because they're surrounded by things like that all day long, and it must make them miserable."[40] His Combine series endowed everyday objects with a new significance by bringing them into the context of fine art alongside traditional painting materials. The Combines eliminated the boundaries between art and sculpture so that both were present in a single work of art. While "Combines" technically refers to Rauschenberg's work from 1954 to 1964, Rauschenberg continued to utilize everyday objects such as clothing, newspaper, urban debris, and cardboard throughout his artistic career.

His transitional pieces that led to the creation of Combines were Charlene (1954) and Collection (1954/1955), where he collaged objects such as scarves, electric light bulbs, mirrors, and comic strips. Although Rauschenberg had implemented newspapers and patterned textiles in his black paintings and Red Paintings, in the Combines he gave everyday objects a prominence equal to that of traditional painting materials. Considered one of the first of the Combines, Bed (1955) was created by smearing red paint across a well-worn quilt, sheet, and pillow. The work was hung vertically on the wall like a traditional painting. Because of the intimate connections of the materials to the artist’s own life, Bed is often considered to be a self-portrait and a direct imprint of Rauschenberg’s interior consciousness. Some critics suggested the work could be read as a symbol for violence and rape,[41] but Rauschenberg described Bed as “one of the friendliest pictures I’ve ever painted.”[42] Among his most famous Combines are those that incorporate taxidermied animals, such as Monogram (1955-1959) which includes a stuffed angora goat, and Canyon (1959), which features a stuffed golden eagle. Although the eagle was salvaged from the trash, Canyon drew government ire due to the 1940 Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.[43]

Critics originally viewed the Combines in terms of their formal qualities: color, texture, and composition. The formalist view of the 1960s was later refuted by critic Leo Steinberg, who said that each Combine was “a receptor surface on which objects are scattered, on which data is entered."[44] According to Steinberg, the horizontality of what he called Rauschenberg's "flatbed picture plane" had replaced the traditional verticality of painting, and subsequently allowed for the uniquely material-bound surfaces of Rauschenberg’s work.

Performance and dance

Rauschenberg began exploring his interest in dance after moving to New York in the early 1950s. He was first exposed to avant-garde dance and performance art at Black Mountain College, where he participated in John Cage's Theatre Piece No. 1 (1952), often considered the first Happening. He began designing sets, lighting, and costumes for Merce Cunningham and Paul Taylor. In the early 1960s he was involved in the radical dance-theater experiments at Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village, and he choreographed his first performance, Pelican (1963), for the Judson Dance Theater in May 1963. Rauschenberg was close friends with Cunningham-affiliated dancers including Carolyn Brown, Viola Farber, and Steve Paxton, all of whom featured in his choreographed works. Rauschenberg's full-time connection to the Merce Cunningham Dance Company ended following its 1964 world tour.[45] In 1977 Rauschenberg, Cunningham, and Cage reconnected as collaborators for the first time in thirteen years to create Travelogue (1977), for which Rauschenberg contributed the costume and set designs.[36] Rauschenberg did not choreograph his own works after 1967, but he continued to collaborate with other choreographers, including Trisha Brown, for the remainder of his artistic career.

Commissions

In 1965, when Life magazine commissioned him to visualize a modern Inferno, he did not hesitate to vent his rage at the Vietnam War and other contemporary sociopolitical issues, including racial violence, neo-Nazism, political assassinations, and ecological disaster.[29] On December 30, 1979 the Miami Herald printed 650,000 Rauschenbergs as the cover of its Sunday magazine, Tropic. In essence an original lithograph, it showed images of south Florida. The artist signed 150 of them.[11]

In 1966, Rauschenberg created the Open Score performance for part of 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering at the 69th Regiment Armory, New York. The series was instrumental in the formation of the Experiments in Art and Technology foundation.[46][47]

In 1983, he won a Grammy Award for his album design of Talking Heads' album Speaking in Tongues.[48] In 1986 Rauschenberg was commissioned by BMW to paint a full size BMW 635 CSi for the sixth installment of the famed BMW Art Car Project. Rauschenberg's contribution was the first to include the wheels in the project, as well as incorporating previous works of art into the design. In 1998, the Vatican commissioned (and later refused)[36] a work by Rauschenberg based on the Apocalypse to commemorate Saint Pio of Pietrelcina, the controversial Franciscan priest who died in 1968 and who is revered for having had stigmata and a saintly aura, at Renzo Piano's Padre Pio Pilgrimage Church in Foggia, Italy.[29]

Works

%2C_1952_(39564308751).jpg) Rauschenberg, untitled (Scatole Personali), 1952, assemblage of box with painted interior, fabric, thorns and snail shells, collection of Jasper Johns

Rauschenberg, untitled (Scatole Personali), 1952, assemblage of box with painted interior, fabric, thorns and snail shells, collection of Jasper Johns.jpg) Rauschenberg, Retroactive II, 1963, combine painting with paint and photos

Rauschenberg, Retroactive II, 1963, combine painting with paint and photos Rauschenberg, untitled, before 1968, combine painting with photos and paint; photo in Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Feb. 1968

Rauschenberg, untitled, before 1968, combine painting with photos and paint; photo in Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Feb. 1968_(34587118200).jpg) Rauschenberg, Tire, in 1996-97 designed; in 2005 made in blown glass and silver-plated brass

Rauschenberg, Tire, in 1996-97 designed; in 2005 made in blown glass and silver-plated brass

Exhibitions

In 1951 Rauschenberg had his first one-man show at the Betty Parsons Gallery[49]. In 1953, while in Italy, he was noted by Irene Brin and Gaspero del Corso and they organized his first European exhibition in their famous gallery in Rome[50]. In 1954 had a second one-man show at the Charles Egan Gallery.[51] In 1955, at the Charles Egan Gallery, Rauschenberg showed Bed (1955), one of his first and certainly most famous Combines.[52]

Rauschenberg had his first career retrospective, organized by the Jewish Museum, New York, in 1963, and in 1964 he was the first American artist to win the Grand Prize at the Venice Biennale (Mark Tobey and James Whistler had previously won the Painting Prize). After that time, he enjoyed a rare degree of institutional support. A retrospective organized by the National Collection of Fine Arts (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum), Washington, D.C., traveled throughout the United States in 1976 and 1978.[36][53] A retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (1997), traveled to Houston, Cologne, and Bilbao (through 1999).[54] Recent exhibitions were presented at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2005; traveled to Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, and Moderna Museet, Stockholm, through 2007); at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (2009; traveled to the Tinguely Museum, Basel, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, and Villa e Collezione Panza, Varese, through 2010); and Botanical Vaudeville at Inverleith House, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (2011).[55]

A memorial exhibition of Rauschenberg's photographs opened October 22, 2008, (on the occasion of what would have been his 83rd birthday) at the Guggenheim Museum.[56]

Further exhibitions include: 5 Decades of Printmaking, Leslie Sacks Contemporary (2012); Robert Rauschenberg: Jammers, Gagosian Gallery, London (2013); Robert Rauschenberg: Hoarfrost Editions, Gemini G.E.L. (2014); Robert Rauschenberg: The Fulton Street Studio, 1953–54, Craig F. Starr Associates (2014); Collecting and Connecting, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University (2014); A Visual Lexicon, Leo Castelli Gallery (2014); Robert Rauschenberg: Works on Metal, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills (2014).;[57] Robert Rauschenberg, de Sarthe Gallery, Hong Kong (2016), Museum of Modern Art retrospective (2017), and Rauschenberg: The 1/4 Mile at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, (2018-2019).[58]

On June 4, 2004 the Gallery of Fine Art at Florida SouthWestern State College was renamed the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery, celebrating a long-time friendship with the artist.[59] The gallery has been host to many of Rauschenberg's exhibitions since 1980.[60]

Legacy

Already in 1984, Rauschenberg announced his Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI) at the United Nations. This would culminate in a seven-year, ten-country tour to encourage "world peace and understanding", through Mexico, Chile, Venezuela, Beijing, Lhasa (Tibet), Japan, Cuba, Soviet Union, Berlin, and Malaysia in which he left a piece of art, and was influenced by the cultures he visited. Paintings, often on reflective surfaces, as well as drawings, photographs, assemblages and other multimedia were produced, inspired by these surroundings, and these were considered some of his strongest works. The ROCI venture, supported by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., went on view in 1991.

In 1990, Rauschenberg created the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation (RRF) to promote awareness of the causes he cared about, such as world peace, the environment and humanitarian issues. He also set up Change, Inc., to award one-time grants of up to $1,000 to visual artists based on financial need. Rauschenberg's will, filed in Probate Court on October 9, 2008, named his charitable foundation as a major beneficiary, along with Darryl Pottorf, Christopher Rauschenberg, Begneaud, his nephew Byron Richard Begneaud, and Susan Weil Kirschenbaum. The amounts to be given to the beneficiaries were not named, but the estate is "worth millions", said Pottorf, who is also executor of the estate.[61]

The RRF today owns many works by Rauschenberg from every period of his career. In 2011, the foundation, in collaboration with Gagosian Gallery, presented "The Private Collection of Robert Rauschenberg", selections from Rauschenberg's personal art collection; proceeds from the collection helped fund the endowment established for the foundation's philanthropic activities.[62] Also in 2011, the foundation launched its "Artist as Activist" print project and invited Shepard Fairey to focus on an issue of his choice. The editioned work he made was sold to raise funds for the Coalition for the Homeless.[63] The RRF artist residency takes place at the late artist's property in Captiva Island, Florida. The foundation also maintains the 19th Street Project Space in New York.

In 2000, Rauschenberg was honored with amfAR's Award of Excellence for Artistic Contributions to the Fight Against AIDS.[64]

Art market

Robert Rauschenberg had his first solo show in 1951, at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York.[65] Later, only after much urging from his wife, Ileana Sonnabend, did Leo Castelli finally organize a solo show for Rauschenberg in the late 1950s.[66] The Rauschenberg estate was long handled by Pace Gallery before, in May 2010,[67] it moved to Gagosian Gallery, a dealership that had first exhibited the artist's work in 1986.[68] In 2010 Studio Painting (1960‑61), one of Rauschenberg's "Combines", originally estimated at $6 million to $9 million, was bought from the collection of Michael Crichton for $11 million at Christie's, New York.[69]

Lobbying for artists' resale royalties

In the early 1970s, Rauschenberg unsuccessfully lobbied U.S. Congress to pass a bill that would compensate artists when their work is resold. The artist later supported a state bill in California that did become law, the California Resale Royalty Act of 1976.[70] Rauschenberg took up his fight for artist resale royalties after the taxi baron Robert Scull sold part of his art collection in a 1973 auction, including Rauschenberg's 1958 painting Thaw that he had originally sold to Scull for $900 but brought $85,000 at an auction at Sotheby Parke Bernet in New York.[71]

See also

References

-

Marlena Donohue (November 28, 1997). "Rauschenberg's Signature on the Century". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on July 7, 2006.

Rauschenberg's mammoth career retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (and other New York sites) from Sept. 19 to Jan. 7, 1998… along with longtime friends pre-Pop painter Jasper Johns and the late conceptual composer John Cage, Rauschenberg pretty much defined the technical and philosophic art landscape and its offshoots after Abstract Expressionism.

-

"The Century's 25 Most Influential Artists". ARTnews. May 1999 – via askART.com.

Born with the name Milton Rauschenberg in Port Arthur, Texas, Robert Rauschenberg became one of the major artists of his generation and is credited along with Jasper Johns of breaking the stronghold of Abstract Expressionism. Rauschenberg was known for assemblage, conceptualist methods, printmaking, and willingness to experiment with non-artistic materials—all innovations that anticipated later movements such as Pop Art, Conceptualism, and Minimalism.

- Lifetime Honors - National Medal of Arts Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- "Leonardo da Vinci World Award of Arts 1995". Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- Franklin Bowles Galleries. "Robert Rauschenberg". FranlinkBowlesGallery.com. Archived from the original on 2007-08-21.

Significantly, given his use of print media imagery, he was also the first living American artist to be featured by Time magazine on its cover.

- "American Art Great Robert Rauschenberg Dies at 82". The Ledger. Archived from the original on May 19, 2008.

- Rauschenberg's Roots, Theind, 2005

- Knight, Christopher (May 14, 2008). "He led the way to Pop Art". Los Angeles Times.

- Hughes, Robert (27 October 1997). "Art: Robert Rauschenberg: The Great Permitter". Time.

- "Robert Rauschenberg". Museum of the Gulf Coast.

- Patricia Burstein (May 19, 1980), In His Art and Life, Robert Rauschenberg Is a Man Who Steers His Own Daring Course People.

- https://www.waddingtoncustot.com/artists/53-robert-rauschenberg/biography/

- Kotz, Mary Lynn (2004). Rauschenberg: Art and Life. New York City: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8109-3752-9.

-

Kotz, Mary Lynn (1990). Rauschenberg: Art and Life. Publishers Weekly. ISBN 0810937522.

Rauschenberg, enfant terrible of American modernism in the 1950s and 1960s, is now an ambassador for global good will. ROCI (Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange), an organization he founded in 1984, sponsors art exhibits and fosters cross-cultural collaborations with the aim of promoting world peace.

"… his boyhood escape from the conformity of the oil town of Port Arthur, Texas, his formative years at Black Mountain College, his political activism in the service of civil rights and peace, and above all, his restless experimentation blurring the boundaries of painting, sculpture, photography, and printmaking.

"… the varied facets of Rauschenberg's output, including his color drawings for Dante's Inferno, his sets for Merce Cunningham's dances, the cardboard-box constructions and the sensual fabric collages and mud sculptures inspired by a 1975 trip to India. - Collins, Bradford R., 1942- (2012). Pop art : the independent group to Neo pop, 1952-90. London: Phaidon. ISBN 9780714862439. OCLC 805600556.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "bauhaus-archiv museum für gestaltung: startseite". Bauhaus.de. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- Tomkins, Calvin, 1925- (2005). Off the wall : a portrait of Robert Rauschenberg (1st Picador ed.). New York: Picador. ISBN 0312425856. OCLC 63193548.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Michael Kimmelman (May 14, 2008). "Robert Rauschenberg, American Artist, Dies at 82". New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- Walter Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s, ISBN 0-940619-07-5

- "The Most Living Artist". Time magazine. November 29, 1976. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- Richard Wood Massi. "Captain Cook's first voyage: an Interview with Morton Feldman". Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- Jonathan Katz. "LOVERS AND DIVERS: INTERPICTORAL DIALOG IN THE WORK OF JASPER JOHNS AND ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG". Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- Ella Nayor,"The Pine Island Eagle, "Bob Rauschenberg, art giant, dead at 82", May 13, 2008

- Kimmelman, Michael (May 13, 2008). "Robert Rauschenberg, American Artist, Dies at 82". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

Robert Rauschenberg, the irrepressibly prolific American artist who time and again reshaped art in the 20th century, died on a Monday night at his home on Captiva Island, Fla. He was 82.

- "Artist Robert Rauschenberg Dead at 82". Voice of America.

- Roberta Smith (1995-02-10). "Art in Review". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- Rauschenberg, Robert; Miller, Dorothy C. (1959). Sixteen Americans [exhibition]. New York: Museum of Modern Art. p. 58. ISBN 978-0029156704. OCLC 748990996. “Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in that gap between the two.)”

- "It's a Roman Holiday for Artists: The American Artists of L'Obelisco After World War II". Center for Italian Modern Art. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

- Richardson, John (September 1997). "Rauschenberg's Epic Vision". Vanity Fair.

- Holland Cotter (June 28, 2012), Robert Rauschenberg: 'North African Collages and Scatole Personali, c. 1952' New York Times.

- "Explore Modern Art | Multimedia | Interactive Features | Robert Rauschenberg's Erased de Kooning Drawing". SFMOMA. Archived from the original on 2011-01-06. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- "Robert Rauschenberg Dead at 82". Blouin Artinfo.

- Kristine Stiles & Peter Selz, Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists' Writings (Second Edition, Revised and Expanded by Kristine Stiles) University of California Press 2012, p. 453

- Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art : guide to the collection. [Birmingham, Ala]: Birmingham Museum of Art. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5.

- "Signs of the Times: Robert Rauschenberg's America". Madison Museum of Contemporary Art. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Robert Rauschenberg Archived 2013-01-21 at the Wayback Machine Guggenheim Collection.

- "Pop art - Rauschenberg - Untitled (Red Painting)". Guggenheim Collection. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- Cage, John (1961). Silence. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. pp. 102.

- Rauschenberg, Robert; Rose, Barbara (1987). Rauschenberg. New York: Vintage Books. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-394-75529-8. OCLC 16356539.

- Kimmelman, Michael (2008-05-14). "Robert Rauschenberg, American Artist, Dies at 82". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- "Robert Rauschenberg". The Daily Telegraph. London. 13 May 2008.

- Tomkins, Calvin (Feb. 29, 1964). "Profiles: Moving Out". The New Yorker 40, no. 2. “Rauschenberg is perplexed by such reactions. 'I think of Bed as one of the friendliest pictures I've ever painted,' [Rauschenberg] said recently. 'My fear has always been that someone would want to crawl into it.'” p. 76.

- The New York Times, "MArt's Sale Value? Zero. The Tax Bill? $29 Million, A Catch-22 of Art and Taxes, Starring a Stuffed Eagle" by Cohen, Patricia, July 22, 2012.

- Steinberg, Leo (1972). Other criteria: Confrontations with twentieth-century art. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 90. ISBN 9780226771854.

- Alastair Macaulay (May 14, 2008), Rauschenberg and Dance, Partners for Life New York Times

- ""Robert Rauschenberg – Open Score" Film Screening". 13 January 2008. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008.

- "Robert Rauschenberg : Open Score (performance)". www.fondation-langlois.org.

- Richard Lacayo (May 15, 2008), Robert Rauschenberg: The Wild and Crazy Guy Time.

- The New York Times, May 14, 1951,

- "It's a Roman Holiday for Artists: The American Artists of L'Obelisco After World War II". Center for Italian Modern Art. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

- Stuart Preston, New York Times, December 19, 1954

- Willem de Kooning. "Gallery - The Charles Egan Gallery". The Art Story. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- National Collection of Fine Arts (U.S.); Rauschenberg, Robert; Alloway, Lawrence; Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Art Institute of Chicago; Albright-Knox Art Gallery, eds. (1976). Robert Rauschenberg. Washington: National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0874741704.

- Hopps, W., Rauschenberg, R., Davidson, S., Brown, T., & Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. (1998). Robert Rauschenberg, a retrospective. New York: Guggenheim Museum. ISBN 0-8109-6903-3.

- Robert Rauschenberg Gagosian Gallery.

- Art Daily, Guggenheim Museum Honors Late Artist Robert Rauschenberg With Photographic Tribute, retrieved December 16, 2008

- "Rauschenberg, Robert - 1785 Exhibitions and Events". www.mutualart.com.

- "Rauschenberg: The 1/4 Mile | LACMA". www.lacma.org. Retrieved 2019-01-08.

- "Mission & History – Bob Rauschenberg Gallery". www.rauschenberggallery.com.

- "Bob Rauschenberg at FSW – Bob Rauschenberg Gallery". www.rauschenberggallery.com.

- "Rauschenberg will names charitable causes, family". The News-Press. Fort Myers, Florida. October 9, 2008. p. 19.

- The Private Collection of Robert Rauschenberg, November 3 - December 23, 2011 Gagosian Gallery.

- Cristina Ruiz (28 March 2012), Rauschenberg's foundation could outspend Warhol's The Art Newspaper.

- Award of Excellence for Artistic Contributions to the Fight Against AIDS amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research.

- Michael McNay (13 May 2008), Obituary: Robert Rauschenberg The Guardian

- Andrew Russeth (June 7, 2010), Ten Juicy Tales from the New Leo Castelli Biography, Blouartinfo

- Carol Vogel (September 29, 2010), Pace Gallery to Represent de Kooning Estate New York Times

- Robert Rauschenberg: Jammers, February 16 - March 28, 2013 Gagosian Gallery, London.

- Carol Vogel (May 12, 2010), At Christie's, a $28.6 Million Bid Sets a Record for Johns New York Times.

- Jori Finkel (February 6, 2014), Jori Finkel: Lessons of California's droit de suite debacle Archived 2014-02-28 at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

- Patricia Cohen (November 1, 2011), Artists File Lawsuits, Seeking Royalties New York Times.

Further reading

- Busch, Julia M., A Decade of Sculpture: the New Media in the 1960s (The Art Alliance Press: Philadelphia; Associated University Presses: London, 1974) ISBN 0-87982-007-1, ISBN 978-0-87982-007-7.

- Marika Herskovic, New York School Abstract Expressionists Artists Choice by Artists, (New York School Press, 2000.) ISBN 0-9677994-0-6. p. 8; p. 32; p. 38; p. 294-297.

- Fugelso, Karl. "Robert Rauschenberg's Inferno Illuminations." In: Postmodern Medievalisms. Ed. Richard Utz and Jesse G. Swan (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2004). pp. 47–66.

- Sweeney, Louise M. "Rauschenberg's Worldwide Quest for Art and Ideas," The Christian Science Monitor, May 20, 1991.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Robert Rauschenberg |