Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia

The Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (Russian: Ру́сская Правосла́вная Це́рковь Заграни́цей, romanized: Russkaya Pravoslavnaya Tserkov' Zagranitsey, lit. 'Russian Orthodox Church Abroad'), or ROCOR, is a semi-autonomous part of the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate).

| Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia Ру́сская Правосла́вная Це́рковь Заграни́цей | |

|---|---|

ROCOR headquarters, 75 E 93rd St, New York. | |

| Abbreviation | ROCOR |

| Classification | Eastern Orthodox |

| Primate | Patriarch of Moscow & All Rus' Kirill Metropolitan Hilarion |

| Language | Church Slavonic (worship), Russian (preaching), English (USA, Canada, UK, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand), Spanish (Spain and Latin America), German (Germany), French (France, Switzerland, Canada), Indonesian (Indonesia), Haitian Creole (Haiti) and others |

| Headquarters | Patriarchal: Moscow, Russia Jurisdictional: New York City, NY |

| Territory | Americas Europe Australia New Zealand |

| Founder | Anthony (Khrapovitsky) Anastassy (Gribanovsky) others |

| Independence | 1920 |

| Recognition | Semi-Autonomous by Russian Orthodox Church |

| Separations | Russian Orthodox Autonomous Church (1994, then called the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad) |

| Members | 27,700 in the U.S. (9,000 regular church attendees) [1]

|

| Official website | www.synod.com |

| This article forms part of the series | ||||

| Eastern Orthodox Christianity in North America | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| History | ||||

| People | ||||

| Jurisdictions (list) | ||||

|

||||

| Monasteries | ||||

| List of monasteries in the United States | ||||

| Seminaries | ||||

| Organizations | ||||

|

||||

The ROCOR was established in the early 1920s as a de facto independent ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Eastern Orthodoxy. In the beginning, this was a result of some of the Russian bishops having lost regular liaison with the central church authority in Moscow due to their voluntary exile after the Russian Civil War. They migrated with other Russians to European cities and nations, including Paris and other parts of France, and to the United States and other western countries. Later these bishops rejected the Moscow Patriarchate′s unconditional political loyalty to the Bolshevik regime in the USSR. This loyalty was formally promulgated by the Declaration of 20 July 1927 of Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky), deputy Patriarchal locum tenens. Metropolitan Antony (Khrapovitsky), of Kiev and Galicia, was the founding First Hierarch of the ROCOR.[2]

After 80 years of separation and the fall of the Soviet Union, on 17 May 2007 the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia officially signed the Act of Canonical Communion with the Moscow Patriarchate, restoring the canonical link between the churches. This resulted in a split with the much diminished Russian Orthodox Autonomous Church (ROAC), which remained within the True Orthodoxy movement independent of the Moscow Patriarchate.

The ROCOR jurisdiction has around 400 parishes worldwide and an estimated membership of more than 400,000 people.[3] Of these, 232 parishes and 10 monasteries are in the United States; they have 92,000 declared adherents and over 9,000 regular church attendees.[1] ROCOR has 13 hierarchs, with male and female monasteries in the United States, Canada, and the Americas; Australia, New Zealand, and Western Europe.[4]

Precursors and early history

In May 1919 during the Russian Revolution, the White military forces under Gen Anton Denikin were achieving their peak of success. In the Russian city of Stavropol, then controlled by the White Army, a group of Russian bishops organised an ecclesiastical administration body, the Temporary Higher Church Administration in South–East Russia (Russian: Временное высшее церковное управление на Юго-Востоке России). On 7 November (20 November) 1920, Tikhon, Patriarch of Moscow, his Synod, and the Supreme Church Council in Moscow issued a joint resolution, No. 362, instructing all Russian Orthodox Christian bishops, should they be unable to maintain liaison with the Supreme Church Administration in Moscow, to seek protection and guidance by organizing among themselves. The resolution was believed to effectively legitimise the Temporary Higher Church Administration; it served as the legal basis for the eventual establishment of a completely independent church body.[5]

In November 1920, after the final defeat of the Russian Army in South Russia, a number of Russian bishops evacuated from Crimea to Constantinople, then occupied by British, French, and Italian forces. After learning that Gen Pyotr Wrangel intended to keep his army, they decided to keep the Russian ecclesiastical organisation as a separate entity abroad as well. The Temporary Church Authority met on 19 November 1920, aboard the ship Grand Duke Alexader Mikhailovich (Russian: «Великий князь Александр Михайлович»), presided over by Metropolitan Antony (Khrapovitsky). Metropolitan Antony and Bishop Benjamin (Fedchenkov) were appointed to examine the canonicity of the organization. On 2 December 1920, they received permission from Metropolitan Dorotheos of Prussia, Locum Tenens of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, to establish "for the purpose of the service of the population [...] and to oversee the ecclesiastic life of Russian colonies in Orthodox countries a temporary committee (epitropia) under the authority of the Ecumenical Patriarchate"; the committee was called the Temporary Higher Church Administration Abroad (THCAA).

In Karlovci

On 14 February 1921, Metropolitan Antony (Khrapovitsky) settled in the town of Sremski Karlovci, Serbia (then within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia), where he was given the palace of former Patriarchs of Karlovci (the Patriarchate of Karlovci had been abolished in 1920).[6] In the next months, at the invitation of Patriarch Dimitrije of Serbia, the other eight bishops of the THCAA, including Anastasius (Gribanovsky) and Benjamin (Fedchenkov), as well as numerous priests and monks, relocated to Serbia.[7] On 31 August 1921, the Council of Bishops of the Serbian Church passed a resolution, effective from 3 October, that recognised the THCAA as an administratively independent jurisdiction for exiled Russian clergy outside the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (SHS) as well as for those Russian clergy in the Kingdom who were not in parish or state educational service. The THCAA jurisdiction was extended to hearing divorce cases of exiled Russians.[6]

With the agreement of Patriarch Dimitrije of Serbia, between 21 November and 2 December 1921, the "General assembly of representatives of the Russian Church abroad" (Russian: Всезаграничное Русское Церковное Собрание) took place in Sremski Karlovci. It was later renamed as the "First All-Diaspora Council" and was presided over by Metropolitan Anthony.

The Council established the "Supreme Ecclesiastic Administration Abroad" (SEAA), composed of a patriarchal Locum Tenens, a Synod of Bishops, and a Church Council. The Council decided to appoint Metropolitan Anthony as the Locum Tenens, but he declined to accept the position without permission from Moscow, and instead identified as the President of the SEAA. The Council adopted a number of resolutions and appeals (missives), with the two most notable ones being addressed to the flock of the Russian Orthodox Church ″in diaspora and exile″ («Чадам Русской Православной Церкви, в рассеянии и изгнании сущим») and to the 1922 International Conference in Genoa. The former, adopted with a majority of votes (but not unanimously, Metropolitan Eulogius Georgiyevsky being the most prominent critic of such specific political declarations), expressly proclaimed a political goal of restoring monarchy in Russia with a tsar from the House of Romanov.[8] The appeal to the Genoa Conference, which was published in 1922, called on the world powers to intervene and “help banish Bolshevism” from Russia.[9] The majority of the Council members secretly decided to request that Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich head up the Russian monarchist movement in exile. (But, pursuant to the laws of the Russian Empire, the seniormost surviving male member of the Romanovs was Kirill Vladimirovich, and in August 1924 he proclaimed himself as the Russian Emperor in exile.)[10]

Patriarch Tikhon addressed a decree of 5 May 1922 to Metropolitan Eulogius Georgiyevsky, abolishing the SEAA and declaring the political decisions of the Karlovci Council to be against the position of the Russian Church. Tikhon appointed Metropolitan Eulogius as administrator for the “Russian orthodox churches abroad”.[11] Meeting in Sremski Karlovci on 2 September 1922, pursuant to Tikhon's decree, the Council of Bishops abolished the SEAA, in its place forming the Temporary Holy Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, with Metropolitan Anthony as its head by virtue of seniority. This Synod exercised direct authority over Russian parishes in the Balkans, the Middle East, and the Far East.

In North America, however, a conflict developed among bishops who did not recognize the authority of the Synod, led by Metropolitan Platon (Rozhdestvensky); this group formed the American Metropolia, the predecessor to the OCA. Likewise, in Western Europe, Metropolitan Eulogius (Georgievsky), based in Paris from late 1922, did not recognise the Synod as having more than "a moral authority." Metropolitan Eulogius later broke off from the ROC and in February 1931 joined the Ecumenical Patriarchate. This formed the Patriarchal Exarchate for Orthodox Parishes of Russian Tradition in Western Europe.

On 5 September 1927, the Council of Bishops in Sremski Karlovci, presided over by Metropolitan Anthony, decreed a formal break of liaison with the ″Moscow church authority.″ They rejected a demand by Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky) of Nizhny Novgorod, who was acting on behalf of Locum Tenens (Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy, imprisoned then in the Soviet Gulag, where he later died), to declare political loyalty to the Soviet authorities. The Council of Bishops said that the church administration in Moscow, headed by Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky), was ″enslaved by the godless Soviet power that has deprived it of freedom in its expression of will and canonical governance of the Church.″[12]

While rejecting both the Bolsheviks and Metropolitan Sergius (who in 1943 would be elected as Patriarch), the ROCOR did continue to nominally recognise the authority of the imprisoned Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy. The Council on 9 September stated: "The part of the Russian Church that finds itself abroad considers itself an inseparable, spiritually united branch of the great Russian Church. It doesn't separate itself from its Mother Church and doesn't consider itself autocephalous."[13] Meanwhile, inside the USSR, Metropolitan Sergius′ Declaration caused a schism among the flock of the Patriarch's Church. Many dissenting believers broke ties with Metropolitan Sergius.[3][14]

On 22 June 1934, Metropolitan Sergius and his Synod in Moscow passed judgment on Metropolitan Anthony and his Synod, declaring them to be suspended.[15] Metropolitan Anthony refused to recognize this decision, claiming that it was made under political pressure from Soviet authorities and that Metropolitan Sergius had illegally usurped the position of Locum Tenens. He was supported in this by the Patriarch Varnava of Serbia, who continued to maintain communion with the ROCOR Synod. However, Patriarch Varnava also attempted to mediate between the Karlovci Synod and Metropolitan Sergius in Moscow, and to find a canonically legitimate way to settle the dispute. In early 1934, he had sent a letter to Sergius proposing that the Karlovci bishops be transferred to the jurisdiction of the Serbian Church; the proposal was rejected by Sergius. Sergius continued to demand that all Russian clergy outside the USSR pledge loyalty to the Soviet authorities.[16] Patriarch Varnava's attempts in the mid-1930s to reconcile the rival exile Russian jurisdictions were likewise unsuccessful.[17]

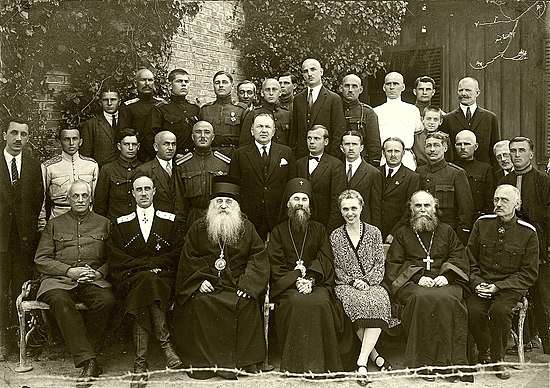

After the deaths of Metropolitan Anthony in August 1936 and Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy in October 1937 (albeit falsely reported a year prior), the Russian bishops in exile held the Second All-Diaspora Council, first in Belgrade, then in Sremski Karlovci, in August 1938.[18] The Council was presided over by Metropolitan Anastasius (Gribanovsky) and attended by 12 other exiled Russian bishops (at least double the number of Orthodox (Patriarchal) bishops who were allowed to serve within the USSR), and 26 priests and 58 laypersons.[19][20] The Council confirmed the leading role of the Church and its bishops in the Russian emigré organisations and adopted two missives: to Russians in the USSR (Russian: «К Русскому народу в Отечестве страждущему») and to the Russian flock in diaspora (Russian: «К Русской пастве в рассеянии сущей»).[21]

From February 1938, Germany′s authorities demanded that all the Russian clergy in the territories controlled by Germany be under the Karlovci jurisdiction (as opposed to that of Paris-based Eulogius). They insisted that an ethnic German, Seraphim Lade, be put in charge of the Orthodox diocese of Berlin.[22]

During World War II and after

The relationship between members of the ROCOR and the Nazis in the run-up to and during World War II has been an issue addressed by both the Church and its critics. Metropolitan Anastassy wrote a letter to Adolf Hitler in 1938, thanking him for his aid to the Russian Diaspora in allowing them to build a Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Berlin and praising his patriotism.[23] This has been defended as an act that occurred when the Metropolitan and others in the church knew "little …of the inner workings of the Third Reich."[24] At the ROCOR Second Church History Conference in 2002, a paper said that “the attempt of the Nazi leadership to divide the Church into separate and even inimical church formations was met with internal church opposition.”[25]

Meanwhile, the USSR leadership's policies towards religion generally and, especially towards the Moscow Patriarchate's jurisdiction in the USSR, changed significantly. In early September 1943, Joseph Stalin met at the Kremlin with a group of three surviving ROC metropolitans headed by Sergius (Stragorodsky). He allowed the Moscow Patriarchate to convene a council and elect a Patriarch, open theological schools, and re-open (keep open) a few major monasteries and some churches (most of which had been re-opened in territory occupied by Germany).[26] The Soviet government decisively sided with the Moscow Patriarchate, while the so-called Obnovlentsi (modernising pro-Soviet current in the ROC), previously favoured by the authorities, were sidelined; their proponents were disappeared shortly after. These developments did not change the mutual rejection between the Moscow Patriarchate and the ROCOR leaderships.

Days after the election in September 1943 of Sergius (Stragorodsky) as Patriarch in Moscow, Metropolitan Anastasius (Gribanovsky) made a statement against recognising this election. The German authorities allowed the ROCOR Synod to hold a convention in Vienna, which took place on 21—26 October 1943. The Synod adopted a resolution declaring the election of Patriarch in Moscow to be uncanonical and hence invalid, and called on all Russian Orthodox faithful to fight against Communism.[27]

On 8 September 1944, days before Belgrade was taken by the Red Army, on the attack from the East, Metropolitan Anastasius (Gribanovsky), along with his office and the other bishops, left Serbia for Vienna.[28] A few months later, they moved to Munich; finally, in November 1950, they immigrated to the United States, together with numerous other Russian Orthodox refugees in the post-war period.

After the end of World War II, the Moscow Patriarchate was the globally dominant branch of Russian Orthodox Christianity. Countries whose Orthodox bishops had been part of the ROCOR in the interwar period, such as Yugoslavia, China, Bulgaria, and East Germany, were now within the USSR-led bloc. Any activity by the ROCOR was politically impossible. A number of ROCOR parishes and clergy, notably Eulogius (Georgiyevsky) (in a jurisdiction under the Ecumenical See since 1931), joined the Moscow Patriarchate, and some repatriated to the USSR.[29]

On the other hand, the ROCOR, by 1950 headquartered in New York, the United States, rejected both the Communist regime in the Soviet Union and the Moscow Patriarchate. Its leaders condemned the Moscow Patriarchate as a Soviet Church run by the secret police.[29]

Conflict with the Moscow Patriarchate after the USSR dissolution

After the end of the Soviet Union in December 1991, ROCOR continued to maintain its administrative independence from the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate).

In May 1990, months prior to the complete disintegration of the USSR, the ROCOR decided to establish new, "Free Russian" parishes in the USSR, and to consecrate bishops to oversee such parishes.

ROCOR and ROC conflict over Palestinian properties

Until well after World War II, most of the Orthodox Church properties in Palestine were controlled by leaders opposed to both the Soviet rule and the Moscow Patriarchate, i.e. mainly within the ROCOR.[30]

When Israel became a state in 1948, it transferred all of the property under the control of the ROCOR within its borders to the Soviet-dominated Russian Orthodox Church in appreciation for Moscow's support of the Jewish state (this support was short-lived).[30] The ROCOR maintained control over churches and properties in the Jordanian-ruled West Bank until the late 1980s.[30] In January 1951, the Soviets reopened the Russian Palestine Society under the direction of Communist Party agents from Moscow, and replaced Archimandrite Vladimir with Ignaty Polikarp, who had been trained by Communists. They attracted numerous Christian Arabs to the ROC who had Communist sympathies. The members of other branches of Orthodoxy refused to associate with the Soviet-led ROC in Palestine.[31]

Decades later, shortly before the fall of the Soviet Union, in 1997 Patriarch of Moscow Alexei II attempted to visit a ROCOR-held monastery in Hebron with Yasser Arafat. "The Moscow-based church has enjoyed a close relationship with Arafat since his guerrilla fighter days."[32] The ROCOR clergy refused to allow Arafat and the patriarch to enter the church, holding that Alexei had no legitimate authority. Two weeks later police officers of the Palestinian Authority arrived; they evicted the ROCOR clergy and turned the property over to the ROC.[30]

Alexei made another visit in early January 2000 to meet with Arafat, asking "for help in recovering church properties"[33] as part of a "worldwide campaign to recover properties lost to churches that split off during the Communist era".[34] Later that month the Palestinian Authority again acted to evict ROCOR clergy, this time from the 3-acre (12,000 m2) Monastery of Abraham's Oak in Hebron.[30][33]

Views on the Moscow Patriarchate, pre-reconciliation

After the declaration of Metropolitan Sergius of 1927, there were a range of opinions regarding the Moscow Patriarchate within ROCOR. A distinction must be made between the various opinions of bishops, clergy, and laity within ROCOR, and official statements from the Synod of Bishops. There was a general belief in ROCOR that the Soviet government was manipulating the Moscow Patriarchate to one extent or another, and that under such circumstances administrative ties were impossible. There were also official statements made that the elections of the patriarchs of Moscow which occurred after 1927 were invalid because they were not conducted freely (without the interference of the Soviets) or with the participation of the entire Russian Church.[35] However, these statements only declared that ROCOR did not recognize the Patriarchs of Moscow who were elected after 1927 as being the legitimate primates of the Russian Church—they did not declare that the Bishops of the Moscow Patriarchate were illegitimate bishops, or without grace. There were, however, under the umbrella of this general consensus, various opinions about the Moscow Patriarchate, ranging for those who held the extreme view that the Moscow Patriarchate had apostatized from the Church (those in the orbit of Holy Transfiguration Monastery being the most vocal advocates of this position), to those who considered them to be innocent sufferers at the hands of the Soviets, and all points in between. Advocates of the more extreme view of the Moscow Patriarchate became increasingly strident in the 1970s, at a time when ROCOR was increasingly isolating itself from much of the rest of the Orthodox Church due to concerns over the direction of Orthodox involvement in the Ecumenical Movement. Prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, there wasn't a burning need to settle the question of what should be made of the status of the Moscow Patriarchate, although beginning in the mid-1980s (as the period of glasnost began in the Soviet Union, which culminated in the ultimate collapse of the Soviet government in 1991), these questions resulted in a number of schisms, and increasingly occupied the attention of those in ROCOR.

There are certain basic facts about the official position of ROCOR that should be understood. Historically, ROCOR has always affirmed that it was an inseparable part of the Russian Church, and that its autonomous status was only temporary, based upon Ukaz 362, until such time as the domination of the Soviet government over the affairs of the Church should cease:

- "The Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia is an indissoluble part of the Russian Orthodox Church, and for the time until the extermination in Russia of the atheist government, is self-governing on conciliar principles in accordance with the resolution of the Patriarch, the Most Holy Synod, and the Highest Church Council [Sobor] of the Russian Church dated 7/20 November 1920, No. 362."[36]

Similarly, Metropolitan Anastassy (Gribanovsky) wrote in his Last Will and Testament:

- "As regards the Moscow Patriarchate and its hierarchs, then, so long as they continue in close, active and benevolent cooperation with the Soviet Government, which openly professes its complete godlessness and strives to implant atheism in the entire Russian nation, then the Church Abroad, maintaining Her purity, must not have any canonical, liturgical or even simply external communion with them whatsoever, leaving each one of them at the same time to the final judgment of the Council (Sobor) of the future free Russian Church."[37]

ROCOR viewed the Russian Church as consisting of three parts during the Soviet period: 1. The Moscow Patriarchate, 2. the Catacomb Church, and 3. The Free Russian Church (ROCOR). The Catacomb Church had been a significant part of the Russian Church prior to World War II. Most of those in ROCOR had left Russia during or well before World War II. They were unaware of the changes that had occurred immediately after World War II—most significantly that with the election of Patriarch Alexei I, most of the Catacomb Church was reconciled with the Moscow Patriarchate. By the 1970s, due to this reconciliation, as well as to continued persecution by the Soviets, there was very little left of the Catacomb Church. Alexander Solzhenitsyn made this point in a letter to the 1974 All-Diaspora Sobor of ROCOR, in which he stated that ROCOR should not "show solidarity with a mysterious, sinless, but also bodiless catacomb."[38]

Movement toward reconciliation with the Moscow Patriarchate

In 2000 Metropolitan Laurus became the First Hierarch of the ROCOR; he expressed interest in the idea of reunification. At the time ROCOR insisted that the Moscow Patriarchate address the murders of Tsar Nicholas II and his family in 1918 by the Bolsheviks. The ROCOR held that "the Moscow Patriarchy must speak clearly and passionately about the murder of the tsar's family, the defeat of the anti-Bolshevik movement, and the execution and persecution of priests."[4] The ROCOR accused the leadership of the ROC as being submissive to the Russian government and were also alarmed by their ties with other denominations of Christianity, especially Catholicism.[4]

At the jubilee Council of Bishops in 2000, the Russian Orthodox Church canonized Tsar Nicholas and his family, along with more than 1,000 martyrs and confessors. This Council also enacted a document on relations between the Church and the secular authorities, censoring servility and complaisance. They also rejected the idea of any connection between Orthodoxy and Catholicism.[4]

In 2001, the Synod of the Patriarchate of Moscow and ROCOR exchanged formal correspondence. The Muscovite letter said that previous and current separation of the religious groups were purely political matters. ROCOR responded that they were still worried about continued Muscovite involvement in ecumenism, suggesting that would compromise Moscow's Orthodoxy. This was more friendly a discourse than in previous decades.

In 2003 President Vladimir Putin of Russia met with Metropolitan Laurus in New York. Patriarch Alexy II of ROC later hailed this event as an important step, saying that it showed the ROCOR that "not a fighter against God, but an Orthodox Christian is at the country's helm."[39]

In May 2004, Metropolitan Laurus, the Primate of the ROCOR, visited Russia participating in several joint services.[40] In June 2004, a contingent of ROCOR clergy met with Patriarch Alexey II. Both parties agreed to set up committees to begin dialogue towards rapprochement. Both sides set up joint commissions, and determined the range of issues to be discussed at the All-Diaspora Council, which met for the first time since 1974.[40]

The possibility of rapprochement, however, led to a minor schism from the ROCOR in 2001.[41][42] ROCOR's former First Hierarch, Metropolitan Vitaly (Oustinoff), and the suspended Bishop Varnava (Prokofieff) of Cannes, were two leaders who did not join this movement. The two formed a loosely associated jurisdiction under the name Russian Orthodox Church in Exile (ROCiE). They claimed that Metropolitan Vitaly's entourage forged his signature on epistles and documents.[43] Bishop Varnava subsequently issued a letter of apology; he was received back into the ROCOR in 2006 as a retired bishop. Even before the death of Metropolitan Vitaly in 2006, the ROCiE began to divide, and its members eventually formed four rival factions, each claiming to be the true ROCOR.

Reconciliation talks

After a series of six reconciliation meetings,[44] the ROCOR and the Patriarchate of Moscow, on June 21, 2005, simultaneously announced that rapprochement talks were leading toward the resumption of full relations between the ROCOR and the Patriarchate of Moscow. They said that the ROCOR would be given autonomous status.[45][46] In this arrangement, the ROCOR was announced to

"join the Moscow Patriarchate as a self-governed branch, similar to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. It will retain its autonomy in terms of pastoral, educational, administrative, economic, property and secular issues."[40]

While Patriarchate Alexy said that the ROCOR would keep its property and fiscal independence, and that its autonomy would not change "in the foreseeable future", he added that "Maybe this will change in decades and there will be some new wishes. But today we have enough concerns and will not make guesses.”[47]

On May 12, 2006, the general congress of the ROCOR confirmed its willingness to reunite with the Russian Orthodox Church. The latter hailed this resolution as:

"an important step toward restoring full unity between the Moscow Patriarchate and the part of the Russian emigration that was isolated from it as a result of the revolution, the civil war in Russia, and the ensuing impious persecution against the Orthodox Church." [48]

In September 2006, the ROCOR Synod of Bishops approved the text of the document worked out by the commissions, an Act of Canonical Communion. In October 2006, the commissions met again to propose procedures and a time for signing the document.[49] The Act of Canonical Communion went into effect upon its confirmation by the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church, based the decision of the Holy Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church on the Relationship with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, held in Moscow on October 3–October 8, 2004; as well as by decision of the Synod of Bishops of the ROCOR, on the basis of the resolution regarding the Act on Canonical Communion of the Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, held in San Francisco on May 15–May 19, 2006.[50]

Signing of the Act of Canonical Communion

On December 28, 2006, the leaders officially announced that the Act of Canonical Communion would be signed. The signing took place on May 17, 2007, followed immediately by a full restoration of communion with the Moscow Patriarchate. It was celebrated by a Divine Liturgy at the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, at which the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia Alexius II and the First Hierarch of ROCOR concelebrated for the first time in history.

On 17 May 2007, at 9:15 a.m., Metropolitan Laurus was greeted at Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Moscow by a special peal of the bells. Shortly thereafter, Patriarch Alexey II entered the Cathedral. After the Patriarch read the prayer for the unity of the Russian Church, the Act of Canonical Communion was read aloud, and two copies were each signed by both Metropolitan Laurus and Patriarch Alexey II. The two hierarchs exchanged the "kiss of peace," and they and the entire Russian Church sang "God Grant You Many Years." Following this, the Divine Liturgy of the Feast of the Ascension of Our Lord began, culminating with the entirety of the bishops of both ROCOR and MP partaking of the Eucharist.

Present at all of this was Russian President Vladimir Putin, who was thanked by Patriarch Alexey for helping to facilitate the reconciliation. Putin addressed the audience of Orthodox Christians, visitors, clergy, and press, saying,

"The split in the church was caused by an extremely deep political split within Russian society itself. We have realized that national revival and development in Russia are impossible without reliance on the historical and spiritual experience of our people. We understand well, and value, the power of pastoral words which unite the people of Russia. That is why restoring the unity of the church serves our common goals."[3]

The Hierarchs of the Russian Church Abroad served again with the Patriarch on 19 May, in the consecration of the Church of the New Martyrs in Butovo firing range. They had laid the cornerstone of the church in 2004 during their initial visit.[51][52] Finally, on Sunday, May 20, they concelebrated in a liturgy at the Cathedral of the Dormition in the Kremlin.

President Vladimir Putin gave a reception at the Kremlin to celebrate the reunification. In attendance were Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow and All Russia and members of the Holy Synod for the Russian Orthodox Church; Metropolitan Laurus for the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia; presidential chief of staff Sergei Sobyanin, First Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, and Minister of Culture and Mass Communications Aleksandr Sokolov. Before the reception the participants posed for photographs by the Assumption Cathedral.[53]

Post-reconciliation schism

Critics of the reunification argue that "the hierarchy in Moscow still has not properly addressed the issue of KGB infiltration of the church hierarchy during the Soviet period."[3][54] Some also note that "some parishes and priests of the ROCOR have always rejected the idea of a reunification with the ROC and said they would leave the ROCOR if this happened. The communion in Moscow may accelerate their departure."[4]

After this act was signed, there was another small schism in the ROCOR: Bishop Agathangel (Pashkovsky) of Odessa and Tauria left, and with him some of ROCOR's parishes in Ukraine. They refused to enter the jurisdiction of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). They had fought schisms resulting in the establishment of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyivan Patriarchate and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, which were both free of Russian influence. Agathangel was subsequently suspended by the ROCOR synod for disobedience.[55][56] Despite censure, Agathangel persisted with the support of ROCOR parishes inside and outside Ukraine which had also refused to submit to the Act of Canonical Communion.[57] Agathangel subsequently ordained Bishop Andronik (Kotliaroff), with the assistance of Greek bishops from the Holy Synod in Resistance; these ordinations signified the breach between ROCOR and those who refused communion with Moscow.[57]

At a Fifth All-Diaspora Council (composed of clergy who did not accept the Act of Canonical Communion), Bishop Agathangel was elevated to the rank of metropolitan. He heads the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad - Provisional Supreme Church Authority (ROCA-PSCA) as Metropolitan Agathangel of New York and Eastern America.[58][59]

Present

ROCOR currently has 593 parishes and 51 monasteries for men and women in 43 countries throughout the world, served by 672 clergy. The distribution of parishes is as follows: 194 parishes and 11 monasteries in the United States; 67 parishes and 11 monasteries in the Australian diocese; 48 parishes in Germany; 25 parishes and 3 monasteries in Canada; 22 parishes in Indonesia. ROCOR churches and communities also exist in Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Denmark, Dominican Republic, France, Haiti, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Luxembourg, Mexico, Morocco, Palestine, Paraguay, Portugal, South Korea, Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, Uganda, United Kingdom, Uruguay and Venezuela.

There are twelve ROCOR monasteries for men and women in North America, the most important and largest of which is Holy Trinity Monastery (Jordanville, New York), to which is attached ROCOR's seminary, Holy Trinity Orthodox Seminary.

The main source of income for the ROCOR central authority is lease of a part of the building that houses the headquarters of the ROCOR's Synod of Bishops situated at the intersection of East 93rd Street and Park Avenue to a private school, estimated in 2016 to generate about $500,000; the ROCOR was said not to make any monetary contributions towards the ROC's budget.[60]

ROCOR oversees and owns properties of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem, which acts as caretaker to three holy sites in East Jerusalem and Palestine, all of which are monasteries.

The current First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church outside Russia is Metropolitan Hilarion (Kapral) (since 28 May 2008).

Western Rite in ROCOR

There is a long history of the Western Rite in ROCOR, although attitudes toward it have varied, and the number of Western Rite parishes is relatively small. St. Petroc Monastery in Tasmania is now under the oversight of Metropolitan Daniel of the Moscow Metropolitanate.[61] Christ the Saviour Monastery, founded in 1993 in Rhode Island and moved to Hamilton, Ontario, in 2008 (see main article for references) has incorporated the Oratory of Our Lady of Glastonbury as its monastery chapel. The oratory had previously been a mission of the Antiochian Western Rite Vicariate in the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America but since October 2007 has been a part of ROCOR. There are a few other parishes that either use the Western Rite exclusively or in part. An American parish, St Benedict of Nursia, in Oklahoma City, uses both the Western Rite and the Byzantine Rite.

In 2011, the ROCOR declared all of its Western Rite parishes to be a "vicariate", parallel to the Antiochian Western Rite Vicariate, and established a website.[62]

On 10 July 2013 an extraordinary session of the Synod of Bishops of ROCOR removed Bishop Jerome of Manhattan and Fr Anthony Bondi from their positions in the vicariate; ordered a halt to all ordinations and a review of those recently conferred by Bishop Jerome; and decreed preparations be made for the assimilation of existing Western Rite communities to mainstream ROCOR liturgical practice.

See also

Notes

- 1.^ The number of adherents given in the "Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches" is defined as "individual full members" with the addition of their children. It also includes an estimate of how many are not members but regularly participate in parish life. Regular attendees includes only those who regularly attend church and regularly participate in church life.[63]

References

- Krindatch, A. (2011). Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches. (p. 80). Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press

- Burlacioiu, Ciprian (April 2018). "Russian Orthodox Diaspora as a Global Religion after 1918". Studies in World Christianity. 24 (1): 4–24. doi:10.3366/swc.2018.0202. ISSN 1354-9901.

- David Holley (May 17, 2007). "Russian Orthodox Church ends 80-year split". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2007-05-20.

- "Russian Orthodox Church reunited: Why only now?". 2007-05-17. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- Положение о Русской Православной Церкви Заграницей: ″Пр. 1. Русская Православная Церковь заграницей есть неразрывная часть поместной Российской Православной Церкви, временно самоуправляющаяся на соборных началах до упразднения в России безбожной власти, в соответствии с Постановлением Св. Патриарха, Св. Синода и Высшего Церковного Совета Российской Церкви от 7/20 ноября 1920 г. за № 362. [...] Пр. 4. Русская Православная Церковь заграницей в своей внутренней жизни и управлении руководствуется: Священным Писанием и Священным Преданием, священными канонами и церковными законами, правилами и благочестивыми обычаями Поместной Российской Православной Церкви и, в частности, — Постановлением Святейшего Патриарха, Свящ. Синода и Высшего Церковного Совета Православной Российской Церкви от 7/20 ноября 1920 года № 362, [...]″

- ″Загранична црква у Сремским Карловцима: Из тајних архива УДБЕ: РУСКА ЕМИГРАЦИЈА У ЈУГОСЛАВИЈИ 1918–1941.″ // Politika, 23 December 2017, p. 22.

- ″Прихваћен позив патријарха Димитрија: Из тајних архива УДБЕ: РУСКА ЕМИГРАЦИЈА У ЈУГОСЛАВИЈИ 1918–1941.″ // Politika, 21 December 2017, p. 25.

- “[...] И ныне пусть неусыпно пламенеет молитва наша – да укажет Господь пути спасения и строительства родной земли; да даст защиту Вере и Церкви и всей земле русской и да осенит он сердце народное; да вернет на всероссийский Престол Помазанника, сильного любовью народа, законного православного Царя из Дома Романовых. [...]” (Протоиерей Аркадий Маковецкий. Белая Церковь: Вдали от атеистического террора: Питер, 2009, ISBN 978-5-49807-400-9 , pp. 31–32).

- Протоиерей Аркадий Маковецкий. Белая Церковь: Вдали от атеистического террора: Питер, 2009, ISBN 978-5-49807-400-9 , p. 35.

- ″У вртлогу политичке борбе: Из тајних архива УДБЕ: РУСКА ЕМИГРАЦИЈА У ЈУГОСЛАВИЈИ 1918–1941.″ // Politika, 15 January 2018, p. 22.

- Протоиерей Аркадий Маковецкий. Белая Церковь: Вдали от атеистического террора: Питер, 2009, ISBN 978-5-49807-400-9 , p. 38.

- Митрополит Антоний (Храповицкий). Избранные труды. Письма. Материалы. Moscow: ПСТГУ, 2007, р. 786: ″«Заграничная часть Всероссийской Церкви должна прекратить сношения с Московской церковной властью ввиду невозможности нормальных сношений с нею и ввиду порабощения её безбожной советской властью, лишающей её свободы в своих волеизъявлениях и каноническом управлении Церковью»″.

- РПЦЗ: КРАТКАЯ ИСТОРИЧЕСКАЯ СПРАВКА: «Заграничная часть Русской Церкви почитает себя неразрывною, духовно-единою ветвью великой Русской Церкви. Она не отделяет себя от своей Матери-Церкви и не считает себя автокефальною».

- Karen Dawisha (1994). Russia and the New States of Eurasia: The Politics of Upheaval. New York, NY: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

- Постановления Заместителя Патриаршего Местоблюстителя и при нем Патриаршего Священного Синода: О Карловацкой группе (от 22 июня 1934 года, № 50) (ЖМП, 1934 г.)

- ″Домети мисије патријарха Варнаве: Из тајних архива УДБЕ: РУСКА ЕМИГРАЦИЈА У ЈУГОСЛАВИЈИ 1918–1941.″ // Politika, 4 January 2018, p. 25.

- ″Нови покушај патријарха Варнаве: Из тајних архива УДБЕ: РУСКА ЕМИГРАЦИЈА У ЈУГОСЛАВИЈИ 1918–1941.″ // Politika, 5 January 2018, p. 18.

- ″Нема Русије без православне монархије: Из тајних архива УДБЕ: РУСКА ЕМИГРАЦИЈА У ЈУГОСЛАВИЈИ 1918–1941.″ // Politika, 6 January 2018, p. 30.

- II Всезарубежный Собор (1938)

- И. М. Андреев. Второй Всезарубежный Собор Русской православной церкви заграницей

- Деяния Второго Всезарубежного Собора Русской Православной Церкви заграницей. Белград, 1939, pp. 18-19.

- прот. Владислав Цыпин. ГЛАВА XI. Церковная диаспора // История Русской Церкви (1917–1997), 1997. Издательство. Издательство Спасо-Преображенского Валаамского монастыря.

- Dimitry Pospielovsky, The Russian Church Under the Soviet Regime 1917–1982, Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir Seminary Press, 1984, p.223

- Archbishop Chrysostomos. "Book Review: The Price of Prophecy". Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- "The Second Ecclesio-Historical Conference "The History of the Russian Orthodox Church of the 20th c. (1930-1948)"". Archived from the original on 2007-06-25.

- Pospielovsky, Dimitry (1998). The Orthodox Church in the History of Russia. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

- Михаил Шкаровский. Политика Третьего рейха по отношению к Русской Православной Церкви в свете архивных материалов 1935—1945 годов / Сборник документов. 2003, стр. 172

- Prof Mikhail Skarovsky. РУССКАЯ ЦЕРКОВНАЯ ЭМИГРАЦИЯ В ЮГОСЛАВИИ В ГОДЫ ВТОРОЙ МИРОВОЙ ВОЙНЫ

- Михаил Шкаровский. Сталинская религиозная политика и Русская Православная Церковь в 1943–1953 годах

- Julie Stahl (28 January 2000). "American Nuns Involved in Jericho Monastery Dispute". CNS. Archived from the original on 2008-01-11.

- "Plot in Progress". Time Magazine. September 15, 1952. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- Abigail Beshkin and Rob Mank (March 24, 2000). "Hunger strike in Jericho". Salon. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-06.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Jerrold Kessel (July 9, 1997). "Russian Orthodox strife brings change in Hebron". CNN.

- "Palestinians Take Sides In Russian Orthodox Dispute". Catholic World News. July 9, 1997. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- See, for example, Resolution of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia Concerning the Election of Pimen (Isvekov) as Patriarch of Moscow, September 1/14) 1971 Archived 2009-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, December 27th, 2007

- Regulations Of The Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, Confirmed by the Council of Bishops in 1956 and by a decision of the Council dated 5/18 June, 1964 Archived 2009-03-30 at the Wayback Machine, first paragraph, December 28, 2007

- The last will and testament of Metropolitan Anastassy, 1957, December 28, 2007

- The Catacomb Tikhonite Church 1974, The Orthodox Word, Nov.-Dec., 1974 (59), 235-246, December 28, 2007.

- "Russian church leader opens Synod's reunification session". 2007-05-16. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- "Russian Church abroad ruling body approves reunion with Moscow". 2006-05-20. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- "Epistle of First-Hierarch, Metropolitan Vitaly, Of ROCOR to All The Faithful Clergy And Flock Of The Church Abroad". Archived from the original on 2008-04-01.

- Archived February 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- The Independent, Obituary: Metropolitan Vitaly Ustinov, 28 September 2006

- "The Sixth Meeting of the Commissions of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia and the Moscow Patriarchate is Held" Archived 2006-09-08 at the Wayback Machine: ROCOR website, downloaded August 25, 2006

- http://www.mospat.ru/text/e_news/id/9553.html. Retrieved July 29, 2005. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "ROCOR website: Joint declarations, April-May 2005". Russianorthodoxchurch.ws. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- "Russian Church To End Schism". Associated Press. May 16, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. "Russian Orthodox Church to keep ROCOR traditions – Alexy II". ITAR-TASS. May 14, 2007. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- "Russian Church abroad to unite with Moscow". Archived from the original on 2007-12-24. RFE/RL website, May 12, 2006

- "The Eighth Meeting of the Church Commissions Concludes": ROCOR website, downloaded November 3, 2006

- "Act of Canonical Communion". Synod.com. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- "Union of Moscow Patriarchate and Russian Church Abroad 17 May 2007":Interfax website, downloaded December 28, 2006

- http://www.orthodoxnews.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=WorldNews.one&content_id=16097&CFID=31445921&CFTOKEN=42692498. Retrieved May 18, 2007. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Putin gives reception for Russian Orthodox Church reunification". 2007-05-19. Archived from the original on 2009-02-14. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- Santana, Rebecca (September 11, 2007). "U.S. Worshipers Refuse to Join Moscow Church". The Associated Press. Associated Press. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- "The Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia - Official Website". Russianorthodoxchurch.ws. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- "Agathangel (Pashkovsky) of Odessa". Orthodoxwiki.org. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- "Russian Orthodox Church Abroad - Provisional Supreme Church Authority". Orthodoxwiki.org. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- "Sinod of Bishops : Russian Orthodox Church Abroad". Sinod.ruschurchabroad.org. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- "Russian Orthodox Church Abroad - Provisional Supreme Church Authority". Sinod.ruschurchabroad.org. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- Расследование РБК: на что живет церковь RBK, 24 February 2017.

- "Saint Petroc Monastery". Orthodoxwesternrite.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- "ROCOR Western-Rite - Home". Rwrv.org. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- Krindatch, A. (2011). Atlas of american orthodox christian churches. (p. x). Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. |

- synod.com Official website of the Synod of bishops of the ROCOR

- fundforassistance.org Official website of the Fund of assistance of the ROCOR

- ROCOR Studies Website dedicated to the history of the ROCOR

- eadiocese.org Official website of the Eastern American diocese

- mcdiocese.com Official website of the diocese of Montreal and Canada

- rocor.org.au Official website of the diocese of Australia and new Zealand

- orthodox-europe.org Official website of Diocese of Great Britain and Western Europe

- chicagodiocese.org Official site of Chicago and Mid-American eprahim

- wadiocese.org Official website of the Western American diocese

- rocor.de Official website of The German diocese

- hts.edu Official website of Holy Trinity Seminary in Jordanville

- rocor-wr.org Western Rite of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia official page

- iglesiarusa.info Official website of The South American diocese