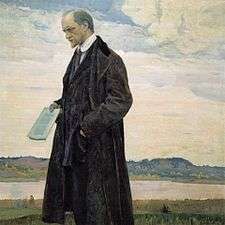

Ivan Ilyin

Ivan Alexandrovich Ilyin (Иван Александрович Ильин, April 9 [O.S. March 28] 1883 – December 21, 1954) was a Russian religious and political philosopher, white émigré publicist and an ideologue of the Russian All-Military Union.

Young years

Ivan Ilyin was born in Moscow in an aristocratic family that claimed Rurikid descent. His father, Alexander Ivanovich Ilyin, had been born and spent his childhood in the Grand Kremlin Palace since Ilyin's grandfather had served as the commandant of the Palace. Alexander Ilyin's godfather had been emperor Alexander III of Russia. Ivan Ilyin's mother, Caroline Louise née Schweikert von Stadion, was a German Russian and confessing Lutheran whose father, Julius Schweikert von Stadion, had been a Collegiate Councillor under the Table of Ranks. She converted to Russian Orthodoxy, took the name Yekaterina Yulyevna, and married Alexander Ilyin in 1880. Ivan Ilyin was brought up also in the centre of Moscow not far from the Kremlin in Naryshkin Lane. In 1901 he entered the Law faculty of the Moscow State University. Ilyin generally disapproved of the Russian Revolution of 1905 and did not participate actively in student political actions. While a student Ilyin became interested in philosophy under influence of Professor Pavel Ivanovich Novgorodtsev (1866-1924), who was a Christian philosopher of jurisprudence and a political liberal. In 1906 Ilyin graduated with a law degree, and from 1909 he began working there as a scholar.

Before the revolution

In 1911, Ilyin moved for a year to Western Europe to work on his thesis: "Crisis of rationalistic philosophy in Germany in the 19th century". He then returned to work in the university and delivered a series of lectures called "Introduction to the Philosophy of Law". Novgorodtsev offered Ilyin to lecture on theory of general law at Moscow Commerce Institute. In total, he lectured at various schools for 17 hours a week.

At that time, Ilyin studied the philosophy of Hegel, particularly his philosophy of state and law. He regarded this work not only as a study of Hegel but also as preparation for his own work on theory of law. His thesis on Hegel was finished in 1916 and published in 1918.

In 1914, after the breakout of World War I, Professor Prince Evgeny Trubetskoy arranged a series of public lectures devoted to the "ideology of the war". Ilyin contributed to this with several lectures, the first of which was called "The Spiritual Sense of the War". He was an utter opponent of any war in general but believed that since Russia had already been involved in the war, the duty of every Russian was to support his country. Ilyin's position was different from that of many Russian jurists, who disliked Germany and Tsarist Russia equally.

Revolution and exile

At first Ilyin perceived the February Revolution as the liberation of the people. Along with many other intellectuals he generally approved of it. However, with the October Revolution complete, disappointment followed. On the Second Moscow Conference of Public Figures he said, "The revolution turned into self-interested plundering of the state". Later, he assessed the revolution as the most terrible catastrophe in the history of Russia, the collapse of the whole state. However, unlike many adherents of the old regime, Ilyin did not emigrate immediately. In 1918, Ilyin became a professor of law in Moscow University; his scholarly thesis on Hegel was published.

After April 1918, Ilyin was imprisoned several times for alleged anti-communist activity. His teacher Novgorodtsev was also briefly imprisoned. In 1922, he was eventually expelled among some 160 prominent intellectuals, on the so-called "philosophers' ship".

Emigration

From 1922 to 1938 he lived in Berlin.[1] He had a German mother and wrote as well in German as in Russian.[2] Between 1923 and 1934, Ilyin worked as a professor of the Russian Scientific Institute in Berlin. He was offered the professorship in the Russian faculty of law in Prague under his teacher Pavel Novgorodtsev but he declined. He became the main ideologue of the Russian White movement in emigration and between 1927 and 1930 was a publisher and editor of the Russian-language journal (Russkiy Kolokol, Russian Bell). He lectured in Germany and other European countries.

In 1934, the German National Socialists sacked Ilyin and put him under police surveillance. In 1938 with financial help from Sergei Rachmaninoff, he was able to leave Germany and continue his work in Geneva, Switzerland. He died in Zollikon near Zürich on December 21, 1954.

Russian President Vladimir Putin was personally involved in moving his remains back to Russia, and in 2009 consecrated his grave.[3]

Doctrine

Ilyin's works about Russia

In exile, Ivan Ilyin argued that Russia should not be judged by the Communist danger it represented at that time but looked forward to a future in which it would liberate itself with the help of Christian Fascism.[4] Starting from his 1918 thesis on Hegel's philosophy, he authored many books on political, social and spiritual topics pertaining to the historical mission of Russia. One of the problems he worked on was the question: what has eventually led Russia to the tragedy of the revolution? He answered that the reason was "the weak, damaged self-respect" of Russians. As a result, mutual distrust and suspicion between the state and the people emerged. The authorities and nobility constantly misused their power, subverting the unity of the people. Ilyin thought that any state must be established as a corporation in which a citizen is a member with certain rights and certain duties. Therefore, Ilyin recognized inequality of people as a necessary state of affairs in any country. But that meant that educated upper classes had a special duty of spiritual guidance towards uneducated lower classes. This did not happen in Russia.

The other point was the wrong attitude towards private property among common people in Russia. Ilyin wrote that many Russians believed that private property and large estates are gained not through hard labour but through power and maladministration of officials. Therefore, property becomes associated with dishonest behaviour.

In his 1949 article, Ilyin argued against both totalitarianism and "formal" democracy in favor of a "third way" of building a state in Russia:[5]

Facing this creative task, appeals of foreign parties to formal democracy remain naive, light-minded and irresponsible.

For Ilyin to talk of a Ukraine separate from Russia was to be a mortal enemy of Russia. He disputed that an individual could choose their nationality any more than cells can decide whether they are part of a body.[6]

The concept of consciousness of law

The two above mentioned factors led to egalitarianism and to revolution. The alternative way of Russia according to Ilyin was to develop due "consciousness of law" of an individual based on morality and religiousness. Ilyin developed his concept of the "consciousness of law" for more than 20 years until his death. He understood it as a proper understanding of law by an individual and ensuing obedience to the law. During his life he refused to publish his major work About the Essence of Consciousness of Law and continued to rewrite it. He considered the consciousness of law as essential for the very existence of law. Without proper understanding of law and justice, the law would not be able to exist.

Attitude towards monarchy

Another major work of Ilyin, "On Monarchy", was not finished. He planned to write a book concerning the essence of monarchy in the modern world and its differences from the republic consisting of twelve chapters, but he died having written the introduction and seven chapters. Ilyin argued that the main difference lay not in legal matters but in the conscience of law of common people. According to Ilyin, the main distinctions were the following:

- in monarchy, the consciousness of law tends to unite the people within the state, but in a republic, the consciousness of law tends to disregard the role of the state for the society;

- monarchical consciousness of law tends to perceive the state as a family and the monarch as a pater familias, but the republican consciousness of law denies this notion. Since the republican conscience of law praises individual freedom in the republican state, people do not recognize the people of the state as a family;

- monarchical conscience of law is very conservative and prone to keeping traditions while republican consciousness of law is always eager to rapid change.

Ilyin was a monarchist. He believed that monarchical consciousness of law corresponds to such values as religious piety and family. His ideal was the monarch who would serve for the good of the country, would not belong to any party and would embody the union of all people, whatever their beliefs are.

However he was critical of the monarchy in Russia. He believed that Nicholas II was to a large degree the one responsible for the collapse of Imperial Russia in 1917. His abdication and the subsequent abdication of his brother Mikhail Alexandrovich were crucial mistakes which led to the abolition of monarchy and consequent troubles.

He was also critical of many figures of the emigration, including Kirill Vladimirovich, Grand Duke of Russia, who had proclaimed himself the new tsar in exile.

View on fascism and antisemitism

A number of Ilyin's works[7][8] (including those written after the German defeat in 1945) advocated fascism.[9] Ilyin saw Hitler as a defender of civilization from Bolshevism and approved the way Hitler had, in his view, derived his antisemitism from the ideology of the Russian Whites.[10]

Although Ilyin was related by marriage to several prominent Jewish families he was accused of antisemitism by Roman Gul, a fellow émigré writer. According to a letter by Gul to Ilyin the former expressed extreme umbrage at Ilyin's suspicions that all those who disagreed with him were Jews.[11]

In his article "The main thing" of "Our Tasks" Ilyin writes: "It is impossible to build the great and powerful Russia on any hatred: not on social class hatred (social-democrats, communists, anarchists), nor on racial hatred (racists, antisemites), nor on political hatred."

Influence

Ilyin's views influenced other 20th-century Russian authors such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn as well as many Russian nationalists. As of 2005, 23 volumes of Ilyin's collected works have been republished in Russia.[12]

The Russian filmmaker Nikita Mikhalkov, in particular, was instrumental in propagating Ilyin's ideas in post-Soviet Russia. He authored several articles about Ilyin and came up with the idea of transferring his remains from Switzerland to the Donskoy Monastery in Moscow, where the philosopher had dreamed to find his last retreat. The ceremony of reburial was held in October 2005.

Following the death of Ilyin's wife in 1963, Ilyin scholar Nikolai Poltoratzky had Ilyin's manuscripts and papers brought from Zurich to Michigan State University, where he was a professor of Russian. In May 2006, MSU transferred Ilyin's papers to the Russian Culture Fund, affiliated with the Russian Ministry of Culture.[13]

Major works

- Hegel's philosophy as a doctrine of the concreteness of God and man (Философия Гегеля как учение о конкретности Бога и человека, 2 vols., 1918; German: Die Philosophie Hegels als kontemplative Gotteslehre, 1946)

- Resistance to Evil By Force (О сопротивлениии злу силою, 1925).

- The Way of Spiritual Revival (1935).

- Foundations of Struggle for the National Russia (1938).

- The Basis of Christian Culture (Основы христианской культуры, 1938).

- About the Future Russia (1948).

- On the Essence of Conscience of Law (О сущности правосознания, 1956).

- The Way to Insight (Путь к очевидности, 1957).

- Axioms of Religious Experience (Аксиомы религиозного опыта, 2 volumes, 1953).

- On Monarchy and Republic (О монархии и республики, 1978).

See also

- Russian philosophy

Notes

- Snyder, Timothy The road to unfreedom : Russia, Europe, America, 2018, p. 19

- Snyder, Timothy The road to unfreedom : Russia, Europe, America, p. 20

- Brooks, David. "Putin Can't Stop". New York Times.

- Snyder, Timothy The road to unfreedom : Russia, Europe, America, p. 21

- "Иван Ильин". www.hrono.ru.

- Snyder, Timothy The road to unfreedom : Russia, Europe, America, p. 23

- "I. Ilyin, National-Socialism: The New Spirit. 1933 (Национал-социализм. Новый дух)". Iljinru.tsygankov.ru. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- "I. Ilyin, On Fascism, 1948 (О фашизме)". Ru-contra.nm.ru. Archived from the original on 2005-02-14. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- Snyder, Timothy (September 20, 2016). "How a Russian Fascist Is Meddling in America's Election". The New York Times. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

Ilyin looked on Mussolini and Hitler as exemplary leaders who were saving Europe by dissolving democracy. His 1927 article “On Russian Fascism” was addressed to “My White brothers, the fascists.” Later, in the 1940s and ’50s, he provided the outlines for a constitution of a fascist Holy Russia governed by a “national dictator” who would be “inspired by the spirit of totality.”

- Snyder, Timothy The road to unfreedom : Russia, Europe, America, p. 20

- Archived July 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Ivan A Il'in. 1993-1999. Sobranie sochinenii [The Collected Works] (10 vols, 6,704pp). Moscow: Russkaia kniga. ISBN 5-268-01393-9.

- "Michigan State University returning papers of late dissident Russian philosopher Ivan Il'in". Newsroom.msu.edu. Archived from the original on 2006-06-13.

References

- History of Russian Philosophy «История российской Философии »(1951) by N. O. Lossky. Publisher: Allen & Unwin, London ASIN: B000H45QTY International Universities Press Inc NY, NY ISBN 978-0-8236-8074-0 sponsored by Saint Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary.