Quetzalcoatl

Quetzalcoatl /ˌkɛtsælkoʊˈɑːtəl/[2] (Spanish: Quetzalcóatl pronounced [ketsalˈkoatl] (![]()

![]()

| Quetzalcoatl | |

|---|---|

| Member of Mesoamerican religion | |

Quetzalcoatl, God of Wind and Wisdom | |

| Other names | Deities: Ehecatl, Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli Nicknames: "Feathered Serpent", "Precious Twin"[1] |

| Major cult center | Temple of the Feathered Serpent, Teotihuacan |

| Planet | Venus |

| Animals | Snake |

| Gender | male |

| Region | Mesoamerica |

| Ethnic group | Aztec, Nahua |

| Festivals | Several |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Mixcoatl and Xochiquetzal |

| Siblings | Xolotl |

The earliest known documentation of the worship of a Feathered Serpent occurs in Teotihuacan in the first century BC or first century AD.[5] That period lies within the Late Preclassic to Early Classic period (400 BC – 600 AD) of Mesoamerican chronology; veneration of the figure appears to have spread throughout Mesoamerica by the Late Classic period (600–900 AD).[6]

In the Postclassic period (900–1519 AD), the worship of the feathered-serpent deity centred in the primary Mexican religious center of Cholula. In this period the deity is known to have been named Quetzalcōhuātl by his Nahua followers. In the Maya area he was approximately equivalent to Kukulkan and Gukumatz, names that also roughly translate as "feathered serpent" in different Mayan languages.

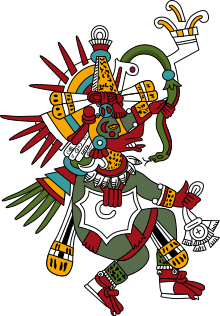

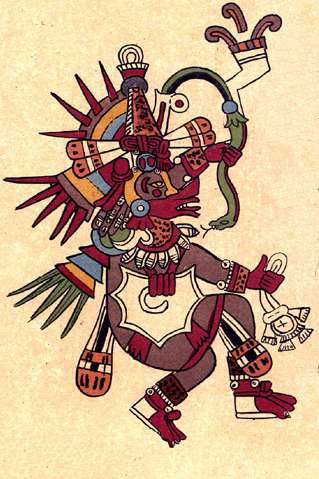

Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec god of wind, air, and learning, wears around his neck the "wind breastplate" ehecailacocozcatl, "the spirally voluted wind jewel" made of a conch shell. This talisman was a conch shell cut at the cross-section and was likely worn as a necklace by religious rulers, as such objects have been discovered in burials in archaeological sites throughout Mesoamerica,[7] and potentially symbolized patterns witnessed in hurricanes, dust devils, seashells, and whirlpools, which were elemental forces that had significance in Aztec mythology. Codex drawings pictured both Quetzalcoatl and Xolotl wearing an ehecailacocozcatl around the neck. Additionally, at least one major cache of offerings includes knives and idols adorned with the symbols of more than one god, some of which were adorned with wind jewels.[8]

In the era following the 16th-century Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, a number of records conflated Quetzalcoatl with Ce Acatl Topiltzin, a ruler of the mythico-historic city of Tollan. Historians debate to what degree, or whether at all, these narratives about this legendary Toltec ruler describe historical events.[9] Furthermore, early Spanish sources written by clerics tend to identify the god-ruler Quetzalcoatl of these narratives with either Hernán Cortés or Thomas the Apostle— identifications which have also become sources of a diversity of opinions about the nature of Quetzalcoatl.[10]

Among the Aztecs, whose beliefs are the best-documented in the historical sources, Quetzalcoatl was related to gods of the wind, of the planet Venus, of the dawn, of merchants and of arts, crafts and knowledge. He was also the patron god of the Aztec priesthood, of learning and knowledge.[11] Quetzalcoatl was one of several important gods in the Aztec pantheon, along with the gods Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli. Two other gods represented by the planet Venus are Quetzalcoatl's ally Tlaloc (the god of rain), and Quetzalcoatl's twin and psychopomp, Xolotl.

Animals thought to represent Quetzalcoatl include resplendent quetzals, rattlesnakes (coatl meaning "serpent" in Nahuatl), crows, and macaws. In his form as Ehecatl he is the wind, and is represented by spider monkeys, ducks, and the wind itself.[12] In his form as the morning star, Venus, he is also depicted as a harpy eagle.[13] In Mazatec legends the astrologer deity Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, who is also represented by Venus, bears a close relationship with Quetzalcoatl.[14]

Feathered serpent deity in Mesoamerica

A feathered serpent deity has been worshiped by many different ethnopolitical groups in Mesoamerican history. The existence of such worship can be seen through studies of the iconography of different Mesoamerican cultures, in which serpent motifs are frequent. On the basis of the different symbolic systems used in portrayals of the feathered serpent deity in different cultures and periods, scholars have interpreted the religious and symbolic meaning of the feathered serpent deity in Mesoamerican cultures.

Iconographic depictions

.jpg)

.jpg)

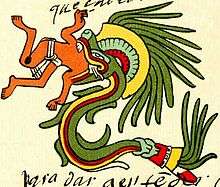

The earliest iconographic depiction of the deity is believed to be found on Stela 19 at the Olmec site of La Venta, depicting a serpent rising up behind a person probably engaged in a shamanic ritual. This depiction is believed to have been made around 900 BC. Although probably not exactly a depiction of the same feathered serpent deity worshipped in classic and post-classic periods, it shows the continuity of symbolism of feathered snakes in Mesoamerica from the formative period and on, for example in comparison to the Maya Vision Serpent shown below.

The first culture to use the symbol of a feathered serpent as an important religious and political symbol was Teotihuacan. At temples such as the aptly named "Quetzalcoatl temple" in the Ciudadela complex, feathered serpents figure prominently and alternate with a different kind of serpent head. The earliest depictions of the feathered serpent deity were fully zoomorphic, depicting the serpent as an actual snake, but already among the Classic Maya, the deity began acquiring human features.

In the iconography of the classic period, Maya serpent imagery is also prevalent: a snake is often seen as the embodiment of the sky itself, and a vision serpent is a shamanic helper presenting Maya kings with visions of the underworld.

The archaeological record shows that after the fall of Teotihuacan that marked the beginning of the epi-classic period in Mesoamerican chronology around 600 AD, the cult of the feathered serpent spread to the new religious and political centers in central Mexico, centers such as Xochicalco, Cacaxtla and Cholula.[6] Feathered serpent iconography is prominent at all of these sites. Cholula is known to have remained the most important center of worship to Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec/Nahua version of the feathered serpent deity, in the post-classic period.

During the epi-classic period, a dramatic spread of feathered serpent iconography is evidenced throughout Mesoamerica, and during this period begins to figure prominently at sites such as Chichén Itzá, El Tajín, and throughout the Maya area. Colonial documentary sources from the Maya area frequently speak of the arrival of foreigners from the central Mexican plateau, often led by a man whose name translates as "Feathered Serpent". It has been suggested that these stories recall the spread of the feathered serpent cult in the epi-classic and early post-classic periods.[6]

Represented as the plumed serpent, Quetzalcoatl was also manifest in the wind, one of the most powerful forces of nature, and this relationship was captured in a text in the Nahuatl language:

Quetzalcoatl; yn ehecatl ynteiacancauh yntlachpancauh in tlaloque, yn aoaque, yn qujqujiauhti. Auh yn jquac molhuja eheca, mjtoa: teuhtli quaqualaca, ycoioca, tetecujca, tlatlaiooa, tlatlapitza, tlatlatzinj, motlatlaueltia.

Quetzalcoatl—he was the wind, the guide and road sweeper of the rain gods, of the masters of the water, of those who brought rain. And when the wind rose, when the dust rumbled, and it crack and there was a great din, became it became dark and the wind blew in many directions, and it thundered; then it was said: "[Quetzalcoatl] is wrathful."[15]

Quetzalcoatl was also linked to rulership and priestly office; additionally, among the Toltec, it was used as a military title and emblem.[16]

In the post-classic Nahua civilization of central Mexico (Aztec), the worship of Quetzalcoatl was ubiquitous. Cult worship may have involved the ingestion of hallucinogenic mushrooms (psilocybes), considered sacred.[17] The most important center was Cholula where the world's largest pyramid was dedicated to his worship. In Aztec culture, depictions of Quetzalcoatl were fully anthropomorphic. Quetzalcoatl was associated with the wind god Ehecatl and is often depicted with his insignia: a beak-like mask.

Interpretations

On the basis of the Teotihuacan iconographical depictions of the feathered serpent, archaeologist Karl Taube has argued that the feathered serpent was a symbol of fertility and internal political structures contrasting with the War Serpent symbolizing the outwards military expansion of the Teotihuacan empire.[18] Historian Enrique Florescano also analyzing Teotihuacan iconography argues that the Feathered Serpent was part of a triad of agricultural deities: the Goddess of the Cave symbolizing motherhood, reproduction and life, Tlaloc, god of rain, lightning and thunder and the feathered serpent, god of vegetational renewal. The feathered serpent was furthermore connected to the planet Venus because of this planet's importance as a sign of the beginning of the rainy season. To both Teotihuacan and Maya cultures, Venus was in turn also symbolically connected with warfare.[19]

While not usually feathered, classic Maya serpent iconography seems related to the belief in a sky-, Venus-, creator-, war- and fertility-related serpent deity. In the example from Yaxchilan, the Vision Serpent has the human face of the young maize god, further suggesting a connection to fertility and vegetational renewal; the Maya Young Maize god was also connected to Venus.

In Xochicalco, depictions of the feathered serpent are accompanied by the image of a seated, armed ruler and the hieroglyph for the day sign 9 Wind. The date 9 Wind is known to be associated with fertility, Venus and war among the Maya and frequently occurs in relation to Quetzalcoatl in other Mesoamerican cultures.

On the basis of the iconography of the feathered serpent deity at sites such as Teotihuacan, Xochicalco, Chichén Itzá, Tula and Tenochtitlan combined with certain ethnohistorical sources, historian David Carrasco has argued that the preeminent function of the feathered serpent deity throughout Mesoamerican history was the patron deity of the Urban center, a god of culture and civilization.[20]

In Aztec culture

To the Aztecs, Quetzalcoatl was, as his name indicates, a feathered serpent, a flying reptile (much like a dragon), who was a boundary-maker (and transgressor) between earth and sky. He was a creator deity having contributed essentially to the creation of mankind. He also had anthropomorphic forms, for example in his aspects as Ehecatl the wind god. Among the Aztecs, the name Quetzalcoatl was also a priestly title, as the two most important priests of the Aztec Templo Mayor were called "Quetzalcoatl Tlamacazqui". In the Aztec ritual calendar, different deities were associated with the cycle-of-year names: Quetzalcoatl was tied to the year Ce Acatl (One Reed), which correlates to the year 1519.[21]

Myths

Attributes

The exact significance and attributes of Quetzalcoatl varied somewhat between civilizations and through history. There are several stories about the birth of Quetzalcoatl. In a version of the myth, Quetzalcoatl was born by a virgin named Chimalman, to whom the god Onteol appeared in a dream.[22] In another story, the virgin Chimalman conceived Quetzalcoatl swallowing an emerald.[23] A third story narrates that Chimalman was hit in the womb by an arrow shot by Mixcoatl and nine months later she gave birth to a child which was called Quetzalcoatl.[22] A fourth story narrates that Quetzalcoatl was born from Coatlicue, who already had four hundred children who formed the stars of the Milky Way.[22]

According to another version of the myth, Quetzalcoatl is one of the four sons of Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, the four Tezcatlipocas, each of whom presides over one of the four cardinal directions. Over the West presides the White Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, the god of light, justice, mercy and wind. Over the South presides the Blue Tezcatlipoca, Huitzilopochtli, the god of war. Over the East presides the Red Tezcatlipoca, Xipe Totec, the god of gold, farming and springtime. And over the North presides the Black Tezcatlipoca, known by no other name than Tezcatlipoca, the god of judgment, night, deceit, sorcery and the Earth.[24] Quetzalcoatl was often considered the god of the morning star, and his twin brother Xolotl was the evening star (Venus). As the morning star, he was known by the title Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, meaning "lord of the star of the dawn". He was known as the inventor of books and the calendar, the giver of maize (corn) to mankind, and sometimes as a symbol of death and resurrection. Quetzalcoatl was also the patron of the priests and the title of the twin Aztec high priests. Some legends describe him as opposed to human sacrifice[25] while others describe him practicing it.[26][27]

Most Mesoamerican beliefs included cycles of suns. Often our current time was considered the fifth sun, the previous four having been destroyed by flood, fire and the like. Quetzalcoatl went to Mictlan, the underworld, and created fifth-world mankind from the bones of the previous races (with the help of Cihuacoatl), using his own blood, from a wound he inflicted on his earlobes, calves, tongue, and penis, to imbue the bones with new life.

It is also suggested that he was a son of Xochiquetzal and Mixcoatl.

In the Codex Chimalpopoca, it is said Quetzalcoatl was coerced by Tezcatlipoca into becoming drunk on pulque, cavorting with his older sister, Quetzalpetlatl, a celibate priestess, and neglecting their religious duties. (Many academics conclude this passage implies incest.) The next morning, Quetzalcoatl, feeling shame and regret, had his servants build him a stone chest, adorn him in turquoise, and then, laying in the chest, set himself on fire. His ashes rose into the sky and then his heart followed, becoming the morning star (see Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli).[28]

Belief in Cortés as Quetzalcoatl

Since the sixteenth century, it has been widely held that the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma II initially believed the landing of Hernán Cortés in 1519 to be Quetzalcoatl's return. This view has been questioned by ethno-historians who argue that the Quetzalcoatl-Cortés connection is not found in any document that was created independently of post-Conquest Spanish influence, and that there is little proof of a pre-Hispanic belief in Quetzalcoatl's return.[29][30][31][32][33] Most documents expounding this theory are of entirely Spanish origin, such as Cortés's letters to Charles V of Spain, in which Cortés goes to great pains to present the naive gullibility of the Aztecs in general as a great aid in his conquest of Mexico.

Much of the idea of Cortés being seen as a deity can be traced back to the Florentine Codex written down some 50 years after the conquest. In the Codex's description of the first meeting between Moctezuma and Cortés, the Aztec ruler is described as giving a prepared speech in classical oratorial Nahuatl, a speech which, as described in the codex written by the Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún and his Tlatelolcan informants, included such prostrate declarations of divine or near-divine admiration as:

You have graciously come on earth, you have graciously approached your water, your high place of Mexico, you have come down to your mat, your throne, which I have briefly kept for you, I who used to keep it for you.

and:

You have graciously arrived, you have known pain, you have known weariness, now come on earth, take your rest, enter into your palace, rest your limbs; may our lords come on earth.

Subtleties in, and an imperfect scholarly understanding of, high Nahuatl rhetorical style make the exact intent of these comments tricky to ascertain, but Restall argues that Moctezuma's politely offering his throne to Cortés (if indeed he did ever give the speech as reported) may well have been meant as the exact opposite of what it was taken to mean: politeness in Aztec culture was a way to assert dominance and show superiority.[34] This speech, which has been widely referred to, has been a factor in the widespread belief that Moctezuma was addressing Cortés as the returning god Quetzalcoatl.

Other parties have also promulgated the idea that the Mesoamericans believed the conquistadors, and in particular Cortés, to be awaited gods: most notably the historians of the Franciscan order such as Fray Gerónimo de Mendieta.[35] Some Franciscans at this time held millennarian beliefs[36] and some of them believed that Cortés' coming to the New World ushered in the final era of evangelization before the coming of the millennium. Franciscans such as Toribio de Benavente "Motolinia" saw elements of Christianity in the pre-Columbian religions and therefore believed that Mesoamerica had been evangelized before, possibly by Thomas the Apostle, who, according to legend, had "gone to preach beyond the Ganges". Franciscans then equated the original Quetzalcoatl with Thomas and imagined that the Indians had long-awaited his return to take part once again in God's kingdom. Historian Matthew Restall concludes that:

The legend of the returning lords, originated during the Spanish-Mexica war in Cortés' reworking of Moctezuma's welcome speech, had by the 1550s merged with the Cortés-as-Quetzalcoatl legend that the Franciscans had started spreading in the 1530s. (Restall 2001 p. 114)

Some scholarship maintains the view that the Aztec Empire's fall may be attributed in part to the belief in Cortés as the returning Quetzalcoatl, notably in works by David Carrasco (1982), H. B. Nicholson (2001 (1957)) and John Pohl (2016). However, a majority of Mesoamericanist scholars, such as Matthew Restall (2003, 2018[34]), James Lockhart (1994), Susan D. Gillespie (1989), Camilla Townsend (2003a, 2003b), Louise Burkhart, Michel Graulich and Michael E. Smith (2003), among others, consider the "Quetzalcoatl/Cortés myth" as one of many myths about the Spanish conquest which have risen in the early post-conquest period.

There is no question that the legend of Quetzalcoatl played a significant role in the colonial period. However, this legend likely has a foundation in events that took place immediately prior to the arrival of the Spaniards. A 2012 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Dallas Museum of Art, "The Children of the Plumed Serpent: the Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico", demonstrated the existence of a powerful confederacy of Eastern Nahuas, Mixtecs and Zapotecs, along with the peoples they dominated throughout southern Mexico between 1200–1600 (Pohl, Fields, and Lyall 2012, Harvey 2012, Pohl 2003). They maintained a major pilgrimage and commercial center at Cholula, Puebla which the Spaniards compared to both Rome and Mecca because the cult of the god united its constituents through a field of common social, political, and religious values without dominating them militarily. This confederacy engaged in almost seventy-five years of nearly continuous conflict with the Aztec Empire of the Triple Alliance until the arrival of Cortés. Members of this confederacy from Tlaxcala, Puebla, and Oaxaca provided the Spaniards with the army that first reclaimed the city of Cholula from its pro-Aztec ruling faction, and ultimately defeated the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan (Mexico City). The Tlaxcalteca, along with other city-states across the Plain of Puebla, then supplied the auxiliary and logistical support for the conquests of Guatemala and West Mexico while Mixtec and Zapotec caciques (Colonial indigenous rulers) gained monopolies in the overland transport of Manila galleon trade through Mexico, and formed highly lucrative relationships with the Dominican order in the new Spanish imperial world economic system that explains so much of the enduring legacy of indigenous life-ways that characterize southern Mexico and explain the popularity of the Quetzalcoatl legends that continued through the colonial period to the present day.

Contemporary use

Latter Day Saints movement

According to the Book of Mormon, the resurrected Jesus Christ descended from heaven and visited the people of the American continent, shortly after his resurrection. Some followers of the Latter Day Saints movement believe that Quetzalcoatl was historically Jesus Christ, but believe his name and the details of the event were gradually lost over time.

Quetzalcoatl is not a religious symbol in the Latter-day Saint faith, and is not taught as such, nor is it in their doctrine that Quetzalcoatl is Jesus.[37] However, one president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, John Taylor, wrote:[38]

The story of the life of the Mexican divinity, Quetzalcoatl, closely resembles that of the Savior; so closely, indeed, that we can come to no other conclusion than that Quetzalcoatl and Christ are the same being. But the history of the former has been handed down to us through an impure Lamanitish source, which has sadly disfigured and perverted the original incidents and teachings of the Savior's life and ministry." (Mediation and Atonement, p. 194.)

Latter-day Saint author Brant Gardner, after investigating the link between Quetzalcoatl and Jesus, concluded that the association amounts to nothing more than folklore.[39] In a 1986 paper for Sunstone, he noted that during the Spanish Conquest, the Native Americans and the Catholic priests who sympathized with them felt pressure to link Native American beliefs with Christianity, thus making the Native Americans seem more human and less savage. Over time, Quetzalcoatl's appearance, clothing, malevolent nature, and status among the gods were reshaped to fit a more Christian framework.[40]

In media

Quetzalcoatl was fictionalized in the 1982 film Q as a monster that terrorizes New York City.[41][42] The deity has been featured as a character in the manga and anime series Yu-Gi-Oh! 5D's, Fate/Grand Order - Absolute Demonic Front: Babylonia, Beyblade: Metal Fusion and Miss Kobayashi's Dragon Maid (the latter depicting Quetzalcoatl as a female dragon deity); the Megami Tensei video game franchise; the video games Fate/Grand Order, Final Fantasy VIII, Final Fantasy XV, Sanitarium, Smite (as an alternate costume for his Mayan counterpart, Kukulkan), and Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine; as the main antagonist in the Star Trek: the Animated Series episode How Sharper Than a Serpent's Tooth; and in the last of The Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel books. Quetzelcoatl also appeared on (Season 3) of the Animal Planet mockumentary Lost Tapes in an episode entitled Q the Serpent God.[43]

In 1971 Tony Shearer published a book called Lord of the dawn: Quetzalcoatl and the Tree of Life, inspiring New Age followers to visit Chichen Itza at the summer solstice when dragon-shaped shadows are cast by the Kulkulcan pyramid.[44]

In popular culture

Beginning during the crisis at Standing Rock in 2016, in parallel with the phrase "Mni Wiconi" ("Water is Life"), support from Mexican, Mexican-American, and Mexican indigenous populations included use of the phrase in Spanish "Agua es Vida". Frequently pictured with this phrase was either Tlaloc or Quetzalcoatl as a serpent, or at times both. Quetzalcoatl being the teotl of life, and Tlaloc being the teotl of rain and sustenance, they are often paired with each other dating back to Pre-Columbian times, and this practice continues today, as was seen in support of the Standing Rock Lakota and in other contemporary struggles for water rights.

Quetzalcoatl appears in the manga and anime series Miss Kobayashi's Dragon Maid, where she is depicted as female. She is usually referred to as "Lucoa" by other characters.

Other uses

Mexico's Flagship Airline Aeroméxico has a Boeing 787-9 Dreamliner painted in a special Quezalcoatl livery.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quetzalcoatl. |

- Aztec mythology in popular culture

- Five Suns, one of Quetzalcōātl and his brothers' legend.

- Quetzalcoatlus, a pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous named after Quetzalcoatl

References

- Jacques Soustelle (1997). Daily Life of the Aztecs. p. 1506.

- "Quetzalcoatl". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- The Nahuatl nouns compounded into the proper name "Quetzalcoatl" are: quetzalli, signifying principally "plumage", but also used to refer to the bird—resplendent quetzal—renowned for its colourful feathers, and cohuātl "snake".

- Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl (2019). History of the Chichimeca Nation: Don Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl's Seventeenth-Century Chronicle of Ancient Mexico.

- "Teotihuacan: Introduction". Project Temple of Quetzalcoatl, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico/ ASU. 20 August 2001. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- Ringle et al. 1998

- De Borhegyi, Stephan F. (1966). "The Wind God's Breastplate". Expedition. Vol. 8 no. 4.

This breastplate, the insignia of the wind god, called in Nahuatl the ehecailacacozcatl, (the 'spirally voluted wind jewel') was made by cutting across the upper portion of a marine conch shell, and drilling holes for suspension by a cord. Such conch shell breastplates were either hung on the sculpture of the god himself or were worn by the high priests, the earthly representatives of this god. According to such sixteenth century Spanish authorities as Fray Bernardino de Sahagun, [...] the title of Quetzalcoatl was reserved for the high priests or pontiffs among the Aztecs and other inhabitants of Mexico. Only they were entitled to wear the emblem of ehecailacacozcatl, the insignia of this god. Such marine shell breastplates are therefore extremely rare. Of the few that survived the Spanish Conquest, most were destroyed by overly zealous friars; only a handful have been turned up by archaeologists.

- "Personified knives". www.mexicolore.co.uk.

- Nicholson 2001, Carrasco 1982, Gillespie 1989, Florescano 2002

- Lafaye 1987, Townsend 2003, Martínez 1980, Phelan 1970

- Smith 2003 p. 213

- "Study the... WIND GOD". www.mexicolore.co.uk.

- de Borhegyi, Carl (30 October 2012). "Evidence of Mushroom Worship in Mesoamerica". The Yucatan Times. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- "The god with the longest name?". www.mexicolore.co.uk.

- Sahagún, Bernardino de (1950). Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. Santa Fe, New Mexico. Book 1, Ch. 5, p. 2.

- Townsend, Richard F. (2009). The Aztecs. Thames & Hudson. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-500-28791-0.

- Guzman, Gaston (2012). "New Taxonomical and Ethnomycological Observations on Psilocybe S.S. (Fungi, Basidiomycota, Agaricomycetidae, Agaricales, Strophariaceae) From Mexico, Africa, and Spain" (PDF). Acta Botanica Mexicana. 100: 88–90. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Florescano 2002 p. 8

- Florescano 2002 p. 821

- Carrasco 1982

- Townsend 2003 p. 668

- J. B. Bierlein, Living Myths. How Myth Gives Meaning to Human Experience, Ballantine Books, 1999

- Carrasco 1982

- Smith 2003

- LaFaye, Jacques (1987). Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe: The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness, 1531–1813 (New ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0226467887.

- Carrasco 1982 p. 145

- Read, Kay Almere (2002). Mesoamerican Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs of Mexico and Central America. Oxford University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0195149098.

- "Readings in Classical Nahuatl: The Death of Quetzalcoatl". pages.ucsd.edu. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Gillespie 1989

- Townsend 2003a

- Townsend 2003b

- Restall 2003a

- Restall 2003b

- Restall, Matthew (2018). When Montezuma Met Cortés: The True Story of the Meeting That Changed History. New York: Harper Collins. p. 345.

- Martinez 1980

- Phelan 1956

- Wirth 2002

- Taylor 1892 p. 201

- Blair 2008

- Gardner 1986

- Ebert, Roger (1 January 1982). "Q Movie Review & Film Summary (1982)". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- Carr, Nick (29 October 2010). "The Complete New York City Horror Movie Marathon!". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- "Lost Tapes Schedule Fallback". 25 September 2014.

- Zolov, Eric (2015). Iconic Mexico: An Encyclopedia from Acapulco to Zócalo [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia from Acapulco to Zócalo. ABC-CLIO. p. 508. ISBN 978-1-61069-044-7.

Bibliography

- Boone, Elizabeth Hill (1989). Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: The Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 79 part 2. Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-792-0. OCLC 20141678.

- Burkhart, Louise M. (1996). Holy Wednesday: A Nahua Drama from Early Colonial Mexico. New cultural studies series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1576-1. OCLC 33983234.

- Carrasco, David (1982). Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of Empire: Myths and Prophecies in the Aztec Tradition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-09490-8. OCLC 0226094871.

- Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxóchitl (2019). History of the Chichimeca Nation: Don Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl's Seventeenth-Century Chronicle of Ancient Mexico. Edited and translated by Amber Brian, Bradley Benton, Peter B. Villella, & Pablo García Loaeza. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-6398-7.

- Florescano, Enrique (1999). The Myth of Quetzalcoatl. Translated by Lysa Hochroth. Raúl Velázquez (illus.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7101-8. OCLC 39313429. Translation of El mito de Quetzalcóatl, original Spanish-language.

- Gardner, Brant (1986). "The Christianization of Quetzalcoatl". Sunstone. 10 (11).

- Gillespie, Susan D (1989). The Aztec Kings: The Construction of Rulership in Mexica History. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1095-4. OCLC 60131674.

- Harvey, Doug (2012). "How a Feathered God Presided Over a Golden Age of Mexican Art". Humanities: The Magazine of the National Endowment of the Humanities. Vol. 33 no. 5. pp. 34–39.

- Hodges, Blair (29 September 2008). "Method and Skepticism (and Quetzalcoatl...)". Life on Gold Plates. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012.

- James, Susan E (Winter 2000). "Some Aspects of the Aztec Religion in the Hopi Kachina Cult". Journal of the Southwest. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. 42 (4): 897–926. ISSN 0894-8410. OCLC 15876763.

- Knight, Alan (2002). Mexico: From the Beginning to the Spanish Conquest. Mexico, vol. 1 of 3-volume series (pbk ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89195-7. OCLC 48249030.

- Lafaye, Jacques (1987). Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe: The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness, 1531–1813. Translated by Benjamin Keen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46788-0.

- Lawrence, D.H. (1925). The Plumed Serpent.

- Locke, Raymond Friday (2001). The Book of the Navajo. Hollaway House.

- Lockhart, James, ed. (1993). We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Repertorium Columbianum, vol. 1. James Lockhart (trans. and notes). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07875-6. OCLC 24703159. (in English, Spanish, and Nahuatl languages)

- Martínez, Jose Luis (1980). "Gerónimo de Mendieta (1980)". Estudios de Cultura Nahuatl. 14.

- Nicholson, H.B. (2001). Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl: the once and future lord of the Toltecs. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-547-4.

- Nicholson, H.B. (2001). The "Return of Quetzalcoatl": did it play a role in the conquest of Mexico?. Lancaster, CA: Labyrinthos.

- Phelan, John Leddy (1970) [1956]. The Millennial Kingdom of the Franciscans in the New World. University of California Press.

- Pohl, John M.D. (2003). "Creation Stories, Hero Cults, and Alliance Building: Postclassic Confederacies of Central and Southern Mexico from A.D. 1150–1458". In Michael Smith; Frances Berdan (eds.). The Postclassic Mesoamerican World. University of Utah Press. pp. 61–66.

- Pohl, John M.D. (2016). "Dramatic Performance and the Theater of the State: The Cults of the Divus Triumphator, Parthenope, and Quetzalcoatl". In John M.D. Pohl; Claire L. Lyons (eds.). Altera Roma: Art and Empire from Mérida to México. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. pp. 127–146.

- Pohl, John M.D.; Virginia M. Fields & Victoria L. Lyall (2012). "Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico: Introduction". Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico. Scala Publishers Ltd. pp. 15–49.

- Restall, Matthew (2003). Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516077-0. OCLC 51022823.

- Restall, Matthew (2003). "Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl: The Once and Future Lord of the Toltecs (review)". Hispanic American Historical Review. 83 (4). doi:10.1215/00182168-83-4-750.

- Ringle, William M.; Tomás Gallareta Negrón; George J. Bey (1998). "The Return of Quetzalcoatl". Ancient Mesoamerica. Cambridge University Press. 9 (2): 183–232. doi:10.1017/S0956536100001954.

- Smith, Michael E. (2003). The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-23015-1. OCLC 48579073.

- Taylor, John (1892) [1882]. An Examination into and an Elucidation of the Great Principle of the Mediation and Atonement of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Deseret News. p. 201.

- Townsend, Camilla (2003). "No one said it was Quetzalcoatl: Listening to the Indians in the conquest of Mexico". History Compass. 1 (1): **. doi:10.1111/1478-0542.034.

- Townsend, Camilla (2003). "Burying the White Gods: New perspectives on the Conquest of Mexico". The American Historical Review. 108 (3). doi:10.1086/ahr/108.3.659.

- Wirth, Diane E (2002). "Quetzalcoatl, the Maya maize god and Jesus Christ". Journal of Book of Mormon Studies. Provo, Utah: Maxwell Institute. 11 (1): 4–15.