Xōchiquetzal

In Aztec mythology, Xochiquetzal (Classical Nahuatl: Xōchiquetzal [ʃoːtʃiˈketsaɬ]), also called Ichpochtli Classical Nahuatl: Ichpōchtli [itʃˈpoːtʃtɬi], meaning "maiden",[1] was a goddess associated with concepts of fertility, beauty, and female sexual power, serving as a protector of young mothers and a patroness of pregnancy, childbirth, and the crafts practiced by women such as weaving and embroidery. In pre-Hispanic Maya culture, a similar figure is Goddess I.

Name

The name Xōchiquetzal is a compound of xōchitl (“flower”) and quetzalli (“precious feather; quetzal tail feather”). In Classical Nahuatl morphology, the first element in a compound modifies the second and thus the goddess' name can literally be taken to mean “flower precious feather” or ”flower quetzal feather”. Her alternative name, Ichpōchtli, corresponds to a personalized usage of ichpōchtli (“maiden, young woman”).

Description

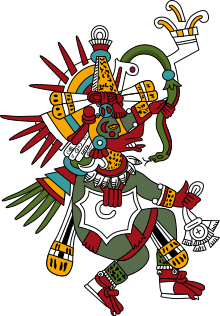

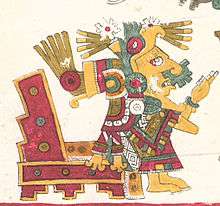

Unlike several other figures in the complex of Aztec female earth deities connected with agricultural and sexual fecundity, Xochiquetzal is always depicted as an alluring and youthful woman, richly attired and symbolically associated with vegetation and in particular flowers. By connotation, Xochiquetzal is also representative of human desire, pleasure, and excess, appearing also as patroness of artisans involved in the manufacture of luxury items.[2]

Worshipers wore animal and flower masks at a festival, held in her honor every eight years. Her husband was Tlaloc until Tezcatlipoca kidnapped her and she was forced to marry him. At one point, she was also married to Centeotl and Xiuhtecuhtli. By Mixcoatl, she was the mother of Quetzalcoatl.

Anthropologist Hugo Nutini identifies her with the Virgin of Ocotlan in his article on patron saints in Tlaxcala.[3]

Notes

- Nahuatl Dictionary. (1997). Wired Humanities Project. University of Oregon. Retrieved September 1, 2012, from link

- Clendinnen (1991, p.163); Miller & Taube (1993, p.190); Smith (2003, p.203)

- Nutini (1976), passim.

References

- Bierhorst, John (1985). A Nahuatl-English Dictionary and Concordance to the Cantares Mexicanos: With an Analytic Transcription and Grammatical Notes. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1183-6. OCLC 11185890.

- Clendinnen, Inga (1991). Aztecs: An Interpretation. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40093-7. OCLC 22451031.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317.

- Nutini, Hugo G. (1976). "Syncretism and Acculturation: The Historical Development of the Cult of the Patron Saint in Tlaxcala, Mexico (1519-1670)". Ethnology. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh. 15 (3): 301–321. doi:10.2307/3773137. ISSN 0014-1828. JSTOR 3773137. OCLC 1568323.

- Smith, Michael E. (2003). The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23015-7. OCLC 48579073.

- Wimmer, Alexis (2006). "Dictionnaire de la langue nahuatl classique" (online version, incorporating reproductions from Dictionnaire de la langue nahuatl ou mexicaine [1885], by Rémi Siméon). (in French and Nahuatl languages)