Pub rock (United Kingdom)

Pub rock is a rock music genre that was developed in the early to mid-1970s in the United Kingdom. A back-to-basics movement which incorporated roots rock, pub rock was a reaction against expensively-recorded and produced progressive rock and flashy glam rock. Although short-lived, pub rock was notable for rejecting huge stadium venues and for returning live rock to the small intimate venues (pubs and clubs) of its early years.[1] Since major labels showed no interest in pub rock groups, pub rockers sought out independent record labels such as Stiff Records. Indie labels used relatively inexpensive recording processes, so they had a much lower break-even point for a record than a major label.

| Pub rock | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | 1970s, London and Essex, United Kingdom |

| Typical instruments | |

| Derivative forms | |

| Other topics | |

| Pub rock (Australia) | |

With pub rock's emphasis on small venues, simple, fairly inexpensive recordings and indie record labels, it was the catalyst for the development of the British punk rock scene. Despite these shared elements, though, there was a difference between the genres: while pub rock harked back to early rock and roll and R&B, punk was iconoclastic, and sought to break with the past musical traditions.

Characteristics

Pub rock was deliberately nasty, dirty and post-glam.[2] Dress style was based around denim and plaid shirts, tatty jeans and droopy hair.[3] The figureheads of the movement, Dr. Feelgood, were noted for their frontman's filthy white suit.[4] Bands looked menacing and threatening, "like villains on The Sweeney".[5] According to David Hepworth, Dr Feelgood looked as if they had "come together in some unsavoury section of the army".

Pub rock groups disdained any form of flashy presentation. Scene leaders like Dr. Feelgood, Kilburn and the High Roads and Ducks Deluxe played simple, "back to mono" rhythm and blues in the tradition of white British groups like The Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds, with fuzzy overdriven guitars and whiny vocals.[5] Lesser acts played funky soul (Kokomo, Clancy, Cado Belle) or country rock (The Kursaal Flyers, Chilli Willi and the Red Hot Peppers).[6] While pub rockers did not have expensive stage shows, they took inspiration from early R&B and increased the dynamism and intensity of their live shows.[7] Pub rock allowed a variety of singers and musicians to perform, even if they did not adhere to a clearly defined musical genre.[7] Major labels scouted pub rock acts, thinking they might find the next Beatles at a local pub; however A&R representatives decided that pub rock did not have potential for mass market hits.[7] With no interest from major labels, pub rockers put out their records through small independent record labels such as Stiff Records and Chiswick Records.[7]

By 1975, the standard for mainstream rock album recordings was expensive, lengthy studio recording processes overseen by highly-paid record producers, with the goal of creating highly polished end products, with overdubs, double-tracking and studio effects. Some mainstream bands spent months in the studio perfecting their recording, to achieve a meticulously crafted and perfect product.[7] Pub rockers rejected this type of costly, complex recording process; instead, with pub rockers, the goal was simply to capture the band's "live" sound and feel in the studio. The difference between mainstream rock and pub rock recording approaches not only produced different sounds (polished vs. raw), it also had a significant impact on the economics of each rock genre. With mainstream rock, the costly sound recording process meant that the break-even point for the record label was around 20,000 records; with pub rock, the less expensive recording process meant that pub rock labels could break even with as few as 2,000 records.[8] This means that pub rock labels could afford to put out records with a tenth of the sales of mainstream bands.

The pub rock scene was primarily a live phenomenon. During the peak years of 1972 to 1975, there was just one solitary Top 20 single (Ace's "How Long"), and all the bands combined sold less than an estimated 150,000 albums.[9] Many acts suffered in the transition from pub to studio recording and were unable to recapture their live sound.[6] The genre's primary characteristic is, as the name suggests, the pub. By championing smaller venues, the bands reinvigorated a local club scene that had dwindled since the 1960s as bands priced themselves into big theatres and stadia.[6] New aspiring bands could now find venues to play without needing to have a record company behind them.

Pub rock was generally restricted to Greater London with some overspill into Essex,[6] although the central belt in Scotland also produced local bands such as The Cheetahs and The Plastic Flies. Pub rockers believed that mainstream stars who played at arenas had lost touch with their audiences. Instead, pub rock groups preferred intimate venues, which were essential to creating meaningful music and connecting with the audience.[10] Pub rock's small venue approach increased the importance of good songwriting and well-written lyrics, in contrast to mainstream pop which had marginalized both elements.[11] The UK pub rock scene wound down by 1976.[8] The record industry was already looking into early punk, thinking it might be the next "big thing". In 1976, some pub rock labels were putting out both the harder-edged pub rock acts and early punk bands such as The Damned.

History

American country-rock band Eggs over Easy were the precursors of the movement when they broke the jazz-only policy of the "Tally Ho" pub in Kentish Town, in May 1971.[12] They were impressive enough to inspire local musicians such as Nick Lowe.[13] They were soon joined by a handful of London acts such as Bees Make Honey, Max Merritt and the Meteors, who actually were from Australia and had moved to London, Ducks Deluxe, The Amber Squad and Brinsley Schwarz who had been victims of the prevailing big-venue system.[6]

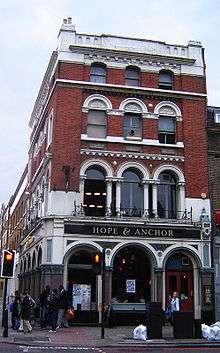

Most of the venues were in large Victorian pubs "north of Regents Park" where there were plenty of suitable pubs.[14] One of the most notable venues was the Hope and Anchor pub on Islington's Upper Street, still a venue.[5]

Following the Tally Ho and the Hope and Anchor came the Cock, the Brecknock, the Lord Nelson, the Greyhound in Fulham, the Red Lion, the Rochester Castle, the Nashville in West Kensington, the Pegasus Pub on Green Lanes, The Torrington in North Finchley, Dingwalls and the Dublin Castle in Camden Town, the Pied Bull at Angel, Bull and Gate in Kentish Town, the Kensington near Olympia, the Newlands Tavern in Nunhead, Half Moon in Putney and Half Moon in Herne Hill (south London outposts) and The Sir George Robey in Finsbury Park. Out of London, venues included the Dagenham Roundhouse, the Grand in Leigh on Sea and the Admiral Jellicoe on Canvey Island.[6] This network of venues later formed a ready-made launch pad for the punk scene.[4]

In 1974, pub rock was the hottest scene in London.[15] At that point it seemed that nearly every large pub in London was supplying live music, along with hot snacks and the occasional stripper.[6] The figureheads were Essex-based R&B outfit Dr. Feelgood.[2] By Autumn 1975, they were joined by acts such as The Stranglers, Roogalator, Eddie and the Hot Rods, Kilburn and the High Roads, and Joe Strummer's 101ers.[16]

Pub rock was rapidly overtaken by the UK punk explosion after spawning what are now seen as several proto-punk bands. Some artists were able to make the transition by jumping ship to new outfits, notably Joe Strummer, Ian Dury and Elvis Costello.[6] A few stalwarts were later able to realise Top 40 chart success, but the moment was gone. Many of the actual pubs themselves survived as punk venues (especially the Nashville and The Hope & Anchor),[6] but a range of notable pubs such as the George Robey and the Pied Bull have since been closed or demolished. The Newlands Tavern survived and is now called The Ivy House.

Legacy

According to Nostalgia Central, "Pub rock may have been killed by punk, but without it there might not have been any punk in Britain at all".[9] The boundaries were originally blurred:[4] at one point, the Hot Rods and the Sex Pistols were both considered rival kings of "street rock".[17] The Pistols played support slots for the Blockheads[18] and the 101ers at the Nashville.[4] Their big break was supporting Eddie and the Hot Rods at the Marquee in Feb 1976.[19] Dr. Feelgood played with the Ramones in New York. The word "punk" debuted on Top of the Pops on a T-shirt worn by a Hot Rod. Punk fanzine Sniffin' Glue reviewed Feelgood album Stupidity as "the way rock should be".[4]

Apart from the ready-made live circuit, punk also inherited the energy of pub rock guitar heroes like Dr. Feelgood's Wilko Johnson, his violence and mean attitude.[4] Feelgood have since been described as John the Baptist to punk's messiahs.[20] In the gap between the music-press hype and vinyl releases of early punk, the rowdier Pub Rock bands even led the charge for those impatient for actual recorded music,[4] but it was not to last.

Punks such as Sex Pistols singer John Lydon eventually rejected the pub rock bands as "everything that was wrong with live music" because they had failed to fight the stadium scene and, as he saw it, preferred to narrow themselves into an exclusive pub clique.[3] The back-to-basics approach of pub rock apparently involved chord structures that were still too complicated for punk guitarists like the Sex Pistols' Steve Jones, who complained "if we had played those complicated chords we would have sounded like Dr. Feelgood or one of those pub rock bands".[21] By the time the Year Zero of punk (1976) was over, punks wanted nothing to do with pub rockers.[22] Bands like The Stranglers were shunned but they didn't care.[23]

It was independent record label Stiff Records, formed from a £400 loan from Feelgood's Lee Brilleaux, who went on to release the first British punk single—The Damned's "New Rose".[23] Stiff Records' early clientele consisted of a mix of pub rockers and punk rock acts for which they became known.

See also

- British popular music

- Garage rock

- List of public house topics

- Mod revival

- New wave music

- Power pop

- Roots rock

- Oi!

- Pub rock (Australia)

References

- "Pub Rock | Music". Britannica.com. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Savage (1991), p. 587.

- Lydon (1995), p. 106.

- Atkinson, Mike. "Give pub rock another chance". The Guardian. 21 January 2010. Retrieved on 19 January 2011.

- Savage (1991), p. 81.

- Carr, Roy. "Pub Rock". NME. 29 October 1977.

- Laing, Dave. One Chord Wonders: Power and Meaning in Punk Rock. PM Press, 2015. p. 18

- Laing, Dave. One Chord Wonders: Power and Meaning in Punk Rock. PM Press, 2015. p. 19

- "Pub Rock". Nostalgiacentral.com. 20 June 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Laing, Dave. One Chord Wonders: Power and Meaning in Punk Rock. PM Press, 2015. p. 17

- Laing, Dave. One Chord Wonders: Power and Meaning in Punk Rock. PM Press, 2015. p. 16

- Birch (2003), pp. 120–129

- "Pub Rock". Archived from the original on 17 July 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- "Pub Rock- Pre Punk music". Punk77.co.uk. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- Savage (1991), p. 80.

- Savage (1991), p. 107 & 124.

- Savage (1991), p. 151.

- Lydon (1995), p. 94.

- Lydon (1995), p. 105.

- "The Dr Feelgood factor | Features | Culture". The Independent. 13 February 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Lydon (1995), p. 87.

- Lydon (1995), p. 107.

- Savage (1991), p. 215.

Sources

- Blaney, John (2011) – A Howlin' Wind: Pub Rock and the Birth of New Wave (London: Soundcheck Books). ISBN 0-9566420-4-7

- Savage, Jon (1991). England's Dreaming: The Sex Pistols and Punk Rock (London: Faber and Faber). ISBN 0-312-28822-0

- Lydon, John (1995). Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs (New York: Picador). ISBN 0-312-11883-X

- Birch, Will (2003). No Sleep Till Canvey Island: The Great Pub Rock Revolution (1st ed. London: Virgin Books) ISBN 0-7535-0740-4.

- Abad, Javier (2002) "Música y Cerveza" (Editorial Milenio. Spain) ISBN 84-9743-041-7

External links

- Southend Music Venues by Southend Sites

- Pub Rock at Nostalgia Central