Rock music and the fall of communism

Rock music played a role in subverting the political order of the Soviet Union and its satellites. The attraction of the unique form of music served to undermine Soviet authority by humanizing the West, helped alienate a generation from the political system, and sparked a youth revolution. This contribution was achieved not only through the use of words or images, but through the structure of the music itself. Furthermore, the music was spread as part of a broad public diplomacy effort, commercial ventures, and through the efforts of the populace in the Eastern Bloc.

In the 1960s, The Beatles sparked the love of rock in the Soviet youth and its popularity spread. In May 1979, Elton John became the first Western rock act to play behind the Iron Curtain, playing eight concerts in the Soviet Union; four dates in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) and four in Moscow.[1] Throughout the 1980s a number of Western acts performed behind the Iron Curtain, including Queen, The Rolling Stones, David Bowie, Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel and Ozzy Osbourne.

History and background

1950s

The stilyagi, the first youth counterculture movement in the Soviet Union, emerged in the 1950s. The stilyagi, meaning stylish in Russian, listened to the music and copied the western fashion trends. Unlike later youth movements, the regime made no attempt to infiltrate and channel the movement toward their own ends, opting instead for public oppression. The stilyagi virtually disappeared by the early 1960s because many restrictions on the flow of information were relaxed, showing that the styles the stilyagi drew inspiration from were outdated.[2][3]

The 6th World Festival of Youth and Students took place in Moscow in 1957, permitting jazz and western forms of dance for one of the first times in the Soviet Union. Although there was some hope that this was an indication of relaxation of restrictions, by the end of the 1950s, Eastern Bloc countries began arresting stilyagi and rock fans.[4] In 1958, partially in response to these events, NATO published a report speculating on the intentional use of rock music for subversive purposes.[5]

1960s

The Beatles sparked the love of rock in the Soviet youth and its popularity spread in the early 1960s.[6] Their impact on fashion was one of the more obvious external signs of their popularity. "Collarless Beatles jackets, known as 'Bitlovka', were assembled from cast-offs; clumsy army boots were refashioned in Beatles style." [7] In addition to their influence in fashion, they also helped drive the expansion of music in the black market. Illicit music albums were created by recording copies onto discarded X-ray emulsion plates.[8] The music itself was acquired either by smuggling copies from the west, or recording it from western radio.[9] The latter became easier and more common after United States president Lyndon Johnson made international broadcasting a priority in the mid-1960s.[10]

Hippie culture emerged in the late 60s and early 70s. Although very similar in terms of aesthetic to their western cousins, Soviet hippies were more passive. The Soviet hippie movement did not develop the same radical social and political sensibilities as did the New Left in the United States.[11] Elsewhere in the eastern bloc, however, rockers and hippies were quite politically active and in the Prague Spring of 1968 numerous concerts were held in support of greater liberalization.[12]

1970s

The major development for rock behind the Iron Curtain in the 1970s was original songs written in the authors' native language. Bands like Illés in Hungary, the Plastic People of the Universe in Czechoslovakia, and Time Machine in the Soviet Union adapted their native languages to rock. They managed to enjoy a steady following, unlike similar attempts by other bands in the 1960s, although they were mostly underground.[13][14] The mainstream was dominated by VIAs (vocal instrument ensembles) which were officially sanctioned rock and pop groups whose lyrics were vetted and whose music was considerably tamer than the underground groups.[15] The East German government even established a bureau for rock, indicating their desire to gain control of the movement.[16]

Although the Seventies were mainly a doldrums for Soviet rock fans, resistance to official policy would still erupt from time to time elsewhere in the bloc, particularly East Germany.[17][18] Even in places where rock's suppression did not produce violent reactions, like Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union itself, the underground continued to flourish, creating a "second culture", which would have dramatic effects in the future.[19]

1980s

In 1980, the Tbilisi Rock Festival was held. The festival was significant because the bands that generated the most "buzz" were not official VIA groups but underground acts like Aquarium.[20] As the 80s progressed, more authentic and "street" oriented groups would gain popularity. Mike Naumenko upset the status quo of even the underground with frank lyrics about life in the Soviet Union; he even addressed taboo subjects such as sex in songs like "Outskirts Blues" and "Ode to the Bathroom".[21] A result of this greater enthusiasm for a genuine native rock scene was a burgeoning home-made album movement. Bands would simply make their own albums; many artists would record copies by using personal reel to reel machines. The finished products were often complete with album art and liner notes, bringing a greater level of quality and sophistication to amateur recordings.[22] By the mid-eighties, under pressure from the Composers' Union and out of concern for the negative effects of rock, the underground and rock music were effectively outlawed. Clubs were closed, rock journalists were censored, popular underground bands were criticized in the press, and official bands were forced to play songs written by the Composers' Union.[23] Elsewhere in the Eastern Bloc, punk was beginning to take hold due to dissatisfaction with political and economic situation for the youth in Czechoslovakia and East Germany.[24]

In 1985, with the election of Gorbachev and the inauguration of glasnost and perestroika, official attitudes toward rock music became much more permissive. At the 12th International Festival of Youth and Students, foreign bands were allowed to play. They ranged from English rock bands, to Finnish punks, to a reggae group that ritually smoked ganja in red square.[25] All these changes inspired the new slang word of the day tusovka - "meaning something's happening, some kind of mess, some activity."[26] When the Rock Lab Festival took place in 1986, the tusovka spirit was on display with Zvuki Mu front man Peter Mamonov singing lyrics like:

I'm dirty, I'm exhausted.

My neck's so thin.

Your hand won't tremble

When you wring it off.

I'm so bad and nasty.

I'm worse than you are.

I'm the most unwanted.

I'm trash, I'm pure dirt.

BUT I CAN FLY![27]

After the Chernobyl disaster, a benefit concert was organized. When government bureaucrats attempted to enforce compliance with a series of regulations and paperwork, the artists and planners simply ignored their requests. There was no official reprimand, confiscation of instruments, or violence from the police in response, something unthinkable even a few years prior.[28] More signs of dissent occurred; at a festival in Petersburg shortly after, the band Televisor stirred the crowd with a song entitled 'Get Out Of Control':

We were watched from the days of kindergarten

Some nice men and kind women

Beat us up. They chose the most painful places

And treated us like animals on the farm.

So we grew up like a disciplined herd.

We sing what they want and live how they want.

And we look at them downside up as if we're trapped.

We just watch how they hit us.

Get out of control.

Get out of control.

And sing what you want.

And not just what is allowed.

We have a right to yell.[29]

Collapse of the Berlin Wall

All over the Eastern Bloc, resistance to rock was being worn down. In 1987, David Bowie, Genesis, and the Eurythmics played in West Berlin. Radio in the American Sector announced the lineup and time well before hand and the concert planners pointed the speakers over the wall so that East Berliners would be ready and could enjoy the concert. When East German security forces tried to disband the crowd of fans assembled by the wall, the fans promptly rioted, chanting "tear down the wall!" In 1988, a similar situation erupted when Michael Jackson performed in West Berlin, and the security forces, while trying to disperse the fans, even attacked western camera crews that were filming the scene.

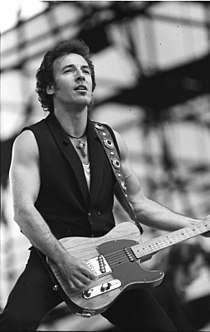

In an attempt to improve its image, the East German government invited Bruce Springsteen to perform in East Berlin in July 1988. No violence erupted during this concert. The crowd joined in enthusiastically while Springsteen was singing "Born in the USA", with many clutching small, hand-painted American flags (something the official East German press neglected to mention).

Additionally, Springsteen said: "I am not for or against any government. I have come here to play rock and roll for you East Berliners in the hope that one day all barriers can be torn down", showing his understanding of the restrictions East Germans faced while avoiding the impression that he was playing in support of the East German government.[30] A few months after that concert, Erich Honecker, the leader of East Germany, resigned.[31] The Berlin Wall itself collapsed in 1989.

Rock's social and political effects

Soviet inflexibility

Thomas Nichols, in "Winning the World," holds that the ideological pronouncements of the Soviet State required that virtually all actions be seen in terms of political import. For example, KGB documents show that the intelligence agency interpreted vigils for John Lennon in 1980 as protests against the regime. The song In the Navy by the Village People was even described by the Soviet press as supporting militarism, an inaccurate claim seeing as the lyrics are a series of thinly veiled references to homosexual behavior. This extreme rigidity in ideology made the Soviet system especially weak in adapting to social changes, and very open to human rights critiques and ridicule.[32]

Viral spread

Artemy Troitsky contends that rock music inspired the same sort of youth revolution that occurred in the west, but the Soviet system could not adapt to the resulting social upheaval.[33] Throughout his book on the Soviet rock movement, Back in the USSR, he describes rock as a virus invading a host body.[34] He also gives accounts of Soviet leadership and bureaucrats describing rock as a form of infection or a virus, supporting his virus metaphor.[35] The main route for "infection" from "alien influences," in his view, came from the problem of permeable borders. The system could never effectively block out all outside influence, nor could it adapt to the ones that came through.[36]

Impact of the Beatles

Leslie Woodhead, in the 2009 documentary "How the Beatles Rocked the Kremlin," argues that rock music, and the Beatles in particular, alienated the youth against the leadership of the Soviet bloc governments. Artemy Troistky, who appeared in the documentary, asserted that the Beatles' appeal reached religious heights. Woodhead supported this assertion by showcasing fan testimony about the Beatles' ubiquitous popularity and the extent to which it still permeates Russian popular culture.[37]

Western radio

The debate over the role of rock in the US public diplomacy effort began almost as soon as it became popular, and lasted through the Reagan administration.[38] "Rock music was blasted to through the Iron Curtain through government-subsidized Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, and we interviewed the legal counsel for VOA who described the debates inside the Reagan administration about the appropriateness of sending "degenerate" rock music eastward. But even the advisory boards came to understand that it was the structure of rock, as much as the lyrics, that counted." [39]

In the mid-60s President Johnson expressed his desire to build cultural and economic bridges with the Soviet Union. This drove intensified radio broadcasts by the VOA, BBC, RFE, and Radio Luxembourg into the Iron Curtain, especially musical programming. All of this was viewed by the Soviets as an overt political subversion campaign. Nevertheless, the Soviet-bloc responded by increasing domestic broadcasts of pop and rock, or big beat as they called it. The results of this saturation of the airwaves with popular music was revealed in a 1966 RFE study of requests from behind the Iron Curtain. The study showed that the taste in music among teenagers from the east and west were largely identical.[40]

Although American funding and support for such broadcasting varied, their broadcasting remained popular. KGB memos asserted that, at one point, 80% of Soviet youth listed to western broadcasts. In addition to the basic popularity of western broadcasts and whatever role that played in undermining the Soviets politically, by the mid 1980s the Soviets were spending more than three billion dollars to jam or block RFE and Radio Liberty broadcasts.[41] Václav Havel attributed this continuous appeal to the inherent rebelliousness of rock music, at least at the time.

The underground and the black market

Magnitizdat were DIY recordings that were the audio counterpart to the written Samizdat. Many of the early DIY recordings were made from plastic X-ray plates [42][43] Rock fans and black marketeers would smuggle records in from the west and would steal discarded X-Ray emulsion plates from dumpsters and garbage cans at hospitals. They would then bring their X-Ray plates and records into small recording studios, which were designed so that Soviet soldiers could record audio messages for family back home. Because the X-ray plates were flexible, they could be rolled and hidden in a sleeve which aided in the concealment and transport of the record.[44] The recordings would still bear images of human skeletons, so they were referred to as "bones," "ribs," or roentgenizdat. This practice began in the 50s, but proliferated in the 60s especially as Beatlemania spread.[45]

It didn't take long before Soviet youth wanted to form bands to emulate the Fab Four, but the lack of instruments was a serious impediment to the formation of rock bands. Soviet youths had to improvise. They did so by creating their own guitars by sawing old tables into the shape of a guitar. Creating pickups and amps was a problem until an inspired young electrical engineer discovered that they could be created from phone receivers and loudspeakers, respectively. The only readily available sources for these items were public telephone booths and speakers used for propaganda broadcasts, so young rockers would vandalize both for parts.[46]

From the early to mid sixties, the subculture was mostly ignored by the authorities. That is not to stay that fans could display their love for rock openly, but it wasn't actively persecuted until later.[47] Most of these new bands would imitate the Beatles as best they could with their improvised instruments, and even clothing fashioned after Beatles stage costumes.[48] They would play anywhere they could; cafes, front stoops, basements, dormitories; anywhere they could convince someone to let them.[49][50] As the bands became more sophisticated and popular, rock scenes began to develop. How the authorities would react depended greatly upon the area and the time period. From the late 60s on, long haired men often would have their offending manes cut and bands would be denied official status, financial support, press coverage, and permission to play in bigger venues. In their place VIA's (the Russian acronym for vocal/instrumental ensemble), officially sanctioned bands were established to play state approved music and lyrics with less "teeth." VIA's would avoid controversial topics in their lyrics, musical styles, or anything deemed "degenerate".[51]

Youth revolution and political disobedience

Despite the attempts to stifle the native rock movement, the underground survived and managed to create a different culture that many would flee to.[52] Identification with this subculture would make one less susceptible to Soviet propaganda and ideology and less likely to view the West as a threat. "The kids lost their interest in all Soviet unshakeable dogmas and ideals, and stopped thinking of an English-speaking person as an enemy. That's when the Communists lost two generations of young people. That was an incredible impact." [53] Even if the individual did not enjoy rock for political reasons, because the political system was opposed to it, merely listening to music was an act of disobedience. By extension, active participation in the underground made one an active agent against the regime, as far as the leadership was concerned.[54] Some of the more dedicated songwriters would go to great lengths to conceal their dissent, which was described in Rockin' the Wall: "The trick was, [ Leslie Mandoki ] noted in the film, to write a "rat tail." The rat tail was a song that ostensibly was about Ronald Reagan or the United States or capitalism—and would therefore clear censors—but which was obvious to all the kids to be a criticism of the Soviet system."[55] The inability of the Communist regimes to eradicate, replace, or assimilate the influence of rock music probably did much to ensure that the populace would turn against the totalitarian system.[56]

See also

References

Footnotes

- "40 Years Ago: Elton John Makes Historic First Tour of Russia". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Troitsky, Artemy (1987). Back in the USSR: The True Story of Rock in Russia. pp. 13–18.

- Ryback, Timothy (1990). Rock Around the Bloc: A History of Rock Music in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, 1954-1988. pp. 9–10.

- Ryback, p. 18.

- Ryback, p. 26.

- Troitsky, p. 23.

- Woodhead, Leslie (2009-09-04). "How the Beatles rocked the Eastern Bloc". BBC. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- Troitsky, p. 19.

- Leif, Mark (Director) (2010-09-01). Rockin' the Wall (Motion picture). USA: Rockin' the Wall Studios.

- Ryback, p. 85.

- Troitsky, p. 30–36.

- Ryback, p. 76-78.

- Ryback, p. 129.

- Troitsky, p. 39–41.

- Troitsky, p. 27.

- Ryback, p. 135.

- Troitsky, p. 38.

- Ryback, p. 190-191.

- Ryback, p. 142–148.

- Troitsky, p. 57-60.

- Troitsky, p. 63–67.

- Troitsky, p. 90-91.

- Troitsky, p. 95-101.

- Ryback, p. 199-205.

- Troitsky, p. 113-115.

- Troitsky, p. 117.

- Troitsky, p. 117-118.

- Troitsky, p. 124–125.

- Troitsky, p. 126-127.

- Ryback, p. 208-210.

- "1989: East Germany leader ousted". BBC. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

- Nichols, Thomas (2002). Winning the World: Lessons for America's Future from the Cold War. Praeger. pp. 39–42.

- Troitsky, p. 8.

- Troitsky, p. 9.

- Troitsky, p. 37.

- Troitsky, p. 9.

- Woodhead, Leslie (2009-11-08). How the Beatles Rocked the Kremlin (Television production). New York, NY: WNET.org. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- Rockin the Wall.

- "Power Chords of Freedom".

- Ryback, p. 85-87.

- Nichols, p. 39.

- Troitsky, p. 19.

- "How the Beatles rocked the Eastern Bloc".

- How the Beatles rocked the Kremlin

- Ryback, p. 32-33.

- How The Beatles Rocked the Kremlin.

- Troitsky, p. 26.

- How the Beatles Rocked the Kremlin

- Troitsky, p. 25.

- How the Beatles Rocked the Kremlin.

- Troitsky, p. 27-28.

- Ryback, p. 142-148.

- "Beatles 'brought down Communism". BBC. 2000-11-17. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- "How the Beatles rocked the Eastern Bloc".

- "Power Chords of Freedom".

- How The Beatles Rocked the Kremlin

Works cited

- Nichols, Thomas (2002). Winning the World: Lessons for America's Future from the Cold War. Praeger.

- Ryback, Timothy (1990). Rock Around the Bloc: A History of Rock Music in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, 1954-1988.

- Troitsky, Artemy (1987). Back in the USSR: The True Story of Rock in Russia. ISBN 0-19-505633-7.

Films

- Leif, Mark (Director) (2010-09-01). Rockin' the Wall (Motion picture). USA: Rockin' the Wall Studios.

- Woodhead, Leslie (2009-11-08). How the Beatles Rocked the Kremlin (Television production). New York, NY: WNET.org. Retrieved 2012-04-18.