Saola

The saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis), also called siola, Vu Quang ox, spindlehorn, Asian unicorn, or, infrequently, the Vu Quang bovid, is one of the world's rarest large mammals, a forest-dwelling bovine found only in the Annamite Range of Vietnam and Laos. Related to cattle, goats, and antelopes,[2][3] the species was described following a discovery of remains in 1992 in Vũ Quang Nature Reserve by a joint survey of the Vietnamese Ministry of Forestry and the World Wide Fund for Nature.[4] Saolas have since been kept in captivity multiple times, although only for short periods. A living saola in the wild was first photographed in 1999 by a camera trap set by WWF and the Vietnamese government's Forest Protection Department (SFNC).[5][6]

| Saola | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Bovinae |

| Tribe: | Bovini |

| Genus: | Pseudoryx Dung, Giao, Chinh, Tuoc, Arctander and MacKinnon, 1993 |

| Species: | P. nghetinhensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Pseudoryx nghetinhensis Dung, Giao, Chinh, Tuoc, Arctander, MacKinnon, 1993 | |

| |

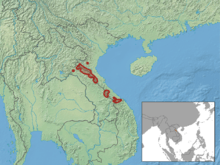

| Range in Vietnam and Laos | |

Etymology

The name 'saola' has been translated as "spindle[-horned]", although the precise meaning is actually "spinning-wheel post horn". The name comes from a Tai language of Vietnam.[7] The meaning is the same in Lao language (ເສົາຫລາ, also spelled ເສົາຫຼາ /sǎo-lǎː/ in Lao). The specific name nghetinhensis refers to the two Vietnamese provinces of Nghệ An and Hà Tĩnh, while Pseudoryx acknowledges the animal's similarities with the Arabian or African oryx. Hmong people in Laos refer to the animal as saht-supahp, a term derived from Lao (ສັດສຸພາບ /sàt supʰáːp/) meaning "the polite animal", because it moves quietly through the forest. Other names used by minority groups in the Saola's range are lagiang (Van Kieu), a ngao (Ta Oi) and xoong xor (Katu) [8] In the press, saolas have been referred to as "Asian unicorns",[9] an appellation apparently due to its rarity and reported gentle nature, and perhaps because both the saola and the oryx have been linked with the unicorn. No known link exists with the Western unicorn myth or the "Chinese unicorn", the qilin.

Discovery

In May 1992, the Ministry of Forestry, Vietnam sent a survey team to examine the biodiversity of the newly established Vu Quang National Park. On this team were Do Tuoc, Le Van Cham and Vu Van Dung (of the Forest Inventory and Planning Institute); Nguyen Van Sang (of the Institute of Ecological and Biological Resources); Nguyen Thai Tu (of Vinh University); and John MacKinnon (of the World Wildlife Fund). On 21 May, the team procured a skull featuring a pair of strange, long and pointed horns from a local hunter. They came across a similar pair in the Annamite Range in the northeastern region of the reserve the following day. The team ascribed these features to a new bovid species, calling it the "saola" or the "Vu Quang ox" to avoid confusion with the sympatric serow. The WWF officially announced the discovery of the new species on 17 July 1992.[10]

According to biodiversity specialist Tony Whitten, though Vietnam boasts a variety of flora and fauna, many of which have been recently described, the discovery of as large an animal as the saola was quite unexpected. The saola was the first large mammal to be discovered in the area for 50 years.[8] Observations of live saola have been few and far between, restricted to the Annamite Range.[9]

Taxonomy and evolution

The scientific name of the saola is Pseudoryx nghetinhensis. It is the sole member of the genus Pseudoryx and is classified under the family Bovidae. The species was first described in 1993 by Vu Van Dung, Do Tuoc, biologists Pham Mong Giao and Nguyen Ngoc Chinh, Peter Arctander of the University of Copenhagen and John MacKinnon.[4] The discovery of saola remains in 1992 generated huge scientific interest due to the animal's special physical traits. The saola differs significantly from all other bovid genera in appearance and morphology, enough to place it in its own genus (Pseudoryx).

A recent sequencing study of ribosomal mitochondrial DNA of a large taxon sample divides the bovid family into two major subfamilial clades. The first clade is the subfamily Bovinae consisting of three tribes: Bovini (cattle and buffaloes), Tragelaphini (Strepsicerotini) (African spiral-horned bovids) and Boselaphini (nilgai and four-horned antelope). The second clade is the subfamily Antelopinae, which includes all other bovids. Antelopinae is composed of the three tribes: Caprini (goats, sheep, and muskox), Hippotragini (horse-like antelopes), and Antilopini (gazelles).

Since its physical traits are so complex to classify, Pseudoryx had been classified variously as member of the subfamily Caprinae and as belonging to any of the three tribes of the subfamily Bovinae: Boselaphini, Bovini and Tragelaphini. DNA analysis has led scientists to place the saola as a member of the tribe Bovini.[11] The morphology of its horns, teeth and some other features indicate it should be grouped with less-derived or more ancestral bovids.[12] Scientific consensus may lead to classifying the saola as the sole member of a proposed new tribe Pseudorygini.

Description

In a 1998 publication, William G. Robichaud, the coordinator of the Saola Working Group, recorded physical measurements for a captive female saola he dubbed 'Martha',[13] in a Laotian menagerie. The animal was observed for around 15 days, until she died from unknown causes. Robichaud noted the height of the female as 84 centimetres (33 in) at the shoulder; the back was slightly elevated, nearly 12 centimetres (4.7 in) taller than the shoulder height. The head-and-body length was recorded as 150 centimetres (4.9 ft).[14] The general characteristics of the saola, as shown by studies during 1993–5 as well as the 1998 study, include a chocolate brown coat with patches of white on the face, throat and the sides of the neck, a paler shade of brown on the neck and the belly, a black dorsal stripe, a pair of nearly parallel horns (present on both sexes).[4][14][15]

Robichaud noted that the hair, straight and 1.5–2.5 centimetres (0.59–0.98 in) long, was soft and thin–a feature unusual for an animal that is associated with montane habitats in at least a few parts of its range. While the hair was found to be short on the head and the neck, it thickened to woolly hair on the insides of the forelegs and the belly. Studies before 1998 reported a hint of red in the inspected skins. The neck and the belly are a paler shade of brown compared to the rest of the body. A common observation in all the three aforementioned studies is a 0.5 centimetres (0.20 in) thick stripe extending from the shoulders to the tail along the middle of the back. From the tip to the end, the tail, that measured 23 centimetres (9.1 in) in Robichaud's specimen, is trifurcated into continuous, horizontal bands of black, white and brown.[4][14][15] Saola skin is 1–2 millimetres (0.039–0.079 in) thick over most of the body, but thickens to 5 millimetres (0.20 in) near the nape of the neck and at the upper shoulders. This adaptation is thought to protect against both predators and rivals' horns during fights.[16]

The saola has round pupils with dark-brown irises that appear orange when light is shone into them; a cluster of white whiskers about 2 centimetres (0.79 in) long with a presumably tactile function protrude from the end of the chin. The specimen Robichaud observed could extend its tongue up to 16 centimetres (6.3 in) and reach its eyes and upper parts of the face; the upper surface of the tongue is covered with fine, backward-pointing barbs. Robichaud observed that either of the two maxillary glands (sinuses) had a nearly rectangular hollow with the dimensions 9×3.5×1.5 centimetres (3.54×1.38×0.59 in), covered by a 0.8 centimetres (0.31 in) thick flap. The maxillary glands of the saola are probably the largest among those of all other animals. The glands are covered by a thick, pungent, grayish green, semi-solid secretion beneath which lies a sheath of few flat hairs. Robichaud observed several pores, used probably for secretion, on the upper surface of the lid. Each white facial spot shelters one or more nodules from which originate 2–2.5 centimetres (0.79–0.98 in) long white or black hairs. These secretions are typically rubbed against the underside of vegetation, leaving a musky, pungent paste. The spoor of the forelegs measured 5–6 centimetres (2.0–2.4 in) long by 5.3–6.4 centimetres (2.1–2.5 in) wide, and 6 centimetres (2.4 in) long by 5.7–6 centimetres (2.2–2.4 in) for the hindlegs.[14]

Both sexes possess slightly divergent horns that are similar in appearance and form almost the same angle with the skull, but differ in their lengths. Horns resemble the parallel wooden posts locally used to support a spinning wheel (thus the familiar name "spindlehorn").[3] These are generally dark-brown or black and about 35–50 cm long; twice the length of their head.[14] Studies in 1993 and 1995 gave the maximum distance between the horn tips of wild specimens as 20 centimetres (7.9 in),[4][15] but the female observed by Robichaud showed a divergence of 25 centimetres (9.8 in) between the tips. Robichaud noted that the horns were 7.5 centimetres (3.0 in) apart at the base. While studies prior to Robichaud's claim the horns are uniformly circular in cross-section, Robichaud observed his specimen had horns with a nearly oval cross-section. The sides of the base of the horns is rugged and indented.[14]

Habitat and distribution

Saola inhabit wet evergreen or deciduous forests in eastern Indochina, preferring rivers and valleys. Sightings have been reported from steep river valleys at 300–1800 m above sea level. In Vietnam and Laos, their range appears to cover approximately 5000 km2, including four nature reserves. During the winters, Saola tend to migrate down to the lowlands.[17]

Ecology and behaviour

Local people reported that the saola is active in the day as well as at night, but prefers resting during the hot midday hours. Robichaud noted that the captive female was active mainly during the day, but pointed out that the observation could have been influenced by the unfamiliar surroundings the animal found herself in. When she rested, she would draw her forelegs inward to her belly, extend her neck so that her chin touched the ground, and close her eyes.[14] Though apparently solitary, saola have been reported in groups of two or three[4] as well as up to six or seven. Grouping patterns of the saola resemble those of the bushbuck, anoa, and sitatunga.[15]

Robichaud observed that the captive female was calm in the presence of humans, but was afraid of dogs. On an encounter with a dog, she would resort to snorting and thrust her head forward, pointing her horns at her opponent. Her erect ears pointed backward, and she stood stiffly with her back arched. Meanwhile, she hardly paid any attention to her surroundings. This female was found to urinate and defecate separately, dropping her hind legs and lowering her lower body – a common observation among bovids. She would spend considerable time grooming herself with her strong tongue. Marking behaviour in the female involved opening up the flap of the maxillary gland and leaving a pungent secretion on rocks and vegetation. She would give out short bleats occasionally.[14]

Diet

Robichaud offered spleenwort (Asplenium) fern species, broad dark-green plants of the genus Homalomena, and various species of broad-leaved shrubs or trees of the subfamily Sterculiaceae to the captive animal. The saola fed on all plants, and showed a preference for the Sterculiaceae species. She did not pull at leaves, she would rather chew or pull them into her mouth using her long tongue. She fed mainly during the day, and rarely in the dark.[14] The saola is also reputed to feed on Schismatoglottis, unlike other herbivores in its range.[18]

Reproduction

Very little information is available about the reproductive cycle of the saola. The saola is likely to have a fixed mating season, from late August to mid-November; only single calf births have been documented, mainly during summer between mid-April and late June.[14][16] In the absence of more specific data, the gestation period has been estimated as similar to that of Tragelaphus species, about 33 weeks.[14] Three reports of saola killings from nearby villagers involved young accompanying mothers. One possessed 9.5 cm (3.7 in) long horns, another an estimated 15 cm (5.9 in), and the third 18.8 cm (7.4 in); these varying horn lengths suggest a birth season extending over at least two to three months.[15]

Conservation

The saola is currently considered to be critically endangered.[1] Its restrictive habitat requirements and aversion to human proximity are likely to endanger it through habitat loss and habitat fragmentation. Saola suffer losses through local hunting and the illegal trade in furs, traditional medicines, and for use of the meat in restaurants and food markets.[19] They also sometimes get caught in snares that have been set to catch animals raiding crops, such as wild boar, sambar, and muntjac. More than 26,651 snares have so far been removed from Saola habitats by conservation groups.[20]

The key feature of the area occupied by the saola is its remoteness from human disturbance.[21] Saola are shot for their meat, but hunters also gain high esteem in the village for the production of a carcass. Due to the scarcity, the locals place much more value on the saola than more common species. Because the people in this area are traditional hunters, their attitude about killing the saola is hard to change; this makes conservation difficult. The intense interest from the scientific community has actually motivated hunters to capture live specimens. Commercial logging has been stopped in the nature reserve area of Bu Huong, and there is an official ban on forest clearance within the boundaries of the reserve.[21]

Species of conservation concern are frequently hard to study; there are often delays in implementing or identifying necessary conservation needs due to lack of data.[22] Because the species is so rare, there is a continuous lack of adequate data; this is one of the major problems facing saola conservation. Trained scientists have never observed saola in the wild. Unfortunately, because it is unlikely that intact saola populations exist, field surveys to discover these populations are not a conservation priority.[22]

The Saola Working Group was formed by the IUCN Species Survival Commission's Asian Wild Cattle Specialist Group, in 2006[23] to protect the saolas and their habitat. This coalition includes about 40 experts from the forestry departments of Laos and Vietnam, Vietnam's Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Vinh University, biologists and conservationists from Wildlife Conservation Society, and the World Wide Fund for Nature.[24]

A group of scientists from the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology in central Hanoi, within the Institute of Biotechnology, investigated a last resort effort of conserving the species by cloning, an extremely difficult approach even in the case of well-understood species.[3] However, the lack of female saola donors (of enucleated ovocytes), receptive females, as well as the interspecific barriers, greatly compromise the success of the cloning technique.[25]

See also

References

- Timmins, R. J.; Hedges, S.; Robichaud, W. (2016). "Pseudoryx nghetinhensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2016: e.T18597A46364962. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T18597A46364962.en. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Artiodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 695. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Stone, R. (2006). "The Saola's Last Stand". Science. 314 (5804): 1380–1383. doi:10.1126/science.314.5804.1380. PMID 17138879.

- Dung, Vu Van; Giao, Pham Mong; Chinh, Nguyen Ngoc; Tuoc, Do; Arctander, Peter; MacKinnon, John (1993). "A new species of living bovid from Vietnam". Nature. 363 (6428): 443–445. doi:10.1038/363443a0.

- "Saola sighting in Vietnam raises hopes for rare mammal's recovery: Long-horned ox photographed in forest in central Vietnam, 15 years after last sighting of threatened species in wild", The Guardian, (November 13 2013).

- "Saola Rediscovered: Rare Photos of Elusive Species from Vietnam", World Wildlife Federation (February 13 2013).

- ""ม้ายูนิคอร์น" แห่งเวียดนามกลับมาให้เห็นอีกครั้งหลังจากหายหน้า 15 ปี". ASTV Manager (in Thai). November 16, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- Cox, S.; Dao, N.T.; Johns, A.G.; Seward, K. (2004). Hardcastle, J. (ed.). Proceedings of the "Rediscovering the saola – a status review and conservation planning workshop", Pu Mat National Park, Con Cuong District, Nghe An Province Vietnam, 27-28 February 2004 (PDF) (Report). Hanoi, Vietnam: WWF Indochina Programme, SFNC Project, Pu Mat National Park. pp. 1–115.

- Moskvitch, K. (16 September 2010). "Rare antelope-like mammal caught in Asia". BBC. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- "Saola still a mystery 20 years after its spectacular debut". World Wildlife Fund. 21 May 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Hassanin, A.; Douzery, E. J. P. (1999). "Evolutionary affinities of the enigmatic saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) in the context of the molecular phylogeny of Bovidae". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 266 (1422): 893–900. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0720. PMC 1689916. PMID 10380679.

- Bibi, Faysal; Vrba, Elisabeth S (2010). "Unraveling bovin phylogeny: Accomplishments and challenges". BMC Biology. 8: 50. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-50. PMC 2861646. PMID 20525112.

- deBuys, William (2015). The Last Unicorn: A Search for One of Earth's Rarest Creatures. Back Bay Books. p. 138.

- Robichaud, W.G. (1998). "Physical and behavioral description of a captive saola, Pseudoryx nghetinhensis" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 79 (2): 394–405. doi:10.2307/1382970. JSTOR 1382970.

- Schaller, G.B.; Rabinowitz, A. (1995). "The saola or spindlehorn bovid Pseudoryx nghetinhensis in Laos". Oryx. 29 (2): 107–114. doi:10.1017/S0030605300020974.

- Huffman, B. "Saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) - Detailed information". Ultimate Ungulate. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- Burgess, Neil (1997). "The Saola (Pseudoryx Nghetinhensis) in Vietnam - New Information on Distribution and Habitat Preferences, and Conservation Needs". GreenFile.

- deBuys, William (2015). The Last Unicorn: A Search for One of Earth's Rarest Creatures. Back Bay Books. p. 163.

- "Saola | Species | WWF." WWF - Endangered Species Conservation World Wide Fund for Nature. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 April 2013

- " Home - Saola Working Group ." N.p., n.d. Web. 18 April 2013

- Kemp, Neville; Dilger, Michael; Burgess, Neil; Dung, Chu Van (2003). "The saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) in Vietnam - new information on distribution and habitat preferences, and conservation needs". Oryx. 31 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3008.1997.d01-86.x.

- Turvey, Samuel T.; Trung, Cao Tien; Quyet, Vo Dai; Nhu, Hoang Van; Thoai, Do Van; Tuan, Vo Cong Anh; Hoa, Dang Thi; Kacha, Kouvang; Sysomphone, Thongsay (2015-04-01). "Interview-based sighting histories can inform regional conservation prioritization for highly threatened cryptic species". Journal of Applied Ecology. 52 (2): 422–433. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12382. ISSN 1365-2664. PMC 4407913. PMID 25926709.

- "Priorities for Success: 2nd Meeting of the Saola Working Group wraps up in Vietnam". IUCN. 2011-05-31.

- "Experts on the saola: The "Last chance" to save one of the world's rarest mammals". Scientific American.

- Rojas, Mariana; Venegas, Felipe; Montiel, Enrique; Servely, Jean Luc; Vignon, Xavier; Guillomot, Michel (2005). "Attempts at Applying Cloning to the Conservation of Species in Danger of Extinction". International Journal of Morphology. 23 (4): 329–336. doi:10.4067/S0717-95022005000400008. ISSN 0717-9502.

Further reading

- DeBuys, William, The Last Unicorn: a Search for One of Earth's Rarest Creatures, Little, Brown and Company, 2015 ISBN 978-0-316-23287-6

- Shuker, Karl P.N. The New Zoo: New and Rediscovered Animals of the Twentieth Century, House of Stratus, 2002 ISBN 978-1842325612

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pseudoryx nghetinhensis. |

- Saola Foundation

- savethesaola.org, Saola Working Group Website

- BBC: Rare antelope-like mammal caught in Asia

- ARKive - images and movies of the saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis)

- Saola factsheet at Ultimate Ungulate

- "A new cow - a new species of ox, the pseudoryx, found in Southeast Asia - 1993 - The Year in Science", from Discover, Jan. 1994.

- The Vu Quang Bovid at BrainBox

- Vu Quang Ox - Pseudoryx nghetinhensis from the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre

- Saola Conservation in Central Vietnam - Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, American Museum of Natural History