Sesklo

Sesklo (Greek: Σέσκλο) is a village in Greece that is located near Volos, a city located within the municipality of Aisonia. The municipality is located within the regional unit of Magnesia that is located within the administrative region of Thessaly.

Sesklo Σέσκλο | |

|---|---|

Sesklo | |

| Coordinates: 39°21.3′N 22°50.1′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Thessaly |

| Regional unit | Magnesia |

| Municipality | Volos |

| Municipal unit | Aisonia |

| Elevation | 200 m (700 ft) |

| Community | |

| • Population | 970 (2011) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 385 00 |

| Area code(s) | 24210 |

| |

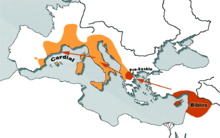

| Alternative names | Map showing the main cultures of Neolithic Greece c. 7000 BC — c. 3200 BC |

|---|---|

| Geographical range | Eastern Europe |

| Period | Neolithic Greece |

| Dates | c. 6850 BC — c. 4400 BC |

| Type site | Sesklo |

| Major sites | Sesklo |

| Preceded by | Neolithic Greece |

| Followed by | Dimini culture, Starčevo–Kőrös–Criș culture |

Sesklo culture

The settlement at Sesklo gives its name to the earliest known Neolithic culture of Europe, which inhabited Thessaly and parts of Macedonia. The Neolithic settlement was discovered in the 1800s and the first excavations were made by the Greek archaeologist, Christos Tsountas.

Pre-Sesklo

The oldest fragments researched at Sesklo place development of the culture as far back as c. 7510 BC — c. 6190 BC, known as proto-Sesklo and pre-Sesklo. They show an advanced agriculture and a very early use of pottery that rivals in age those documented in the near east.

Available data also indicates that domestication of cattle occurred at Argissa as early as c. 6300 BC, during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic.[2] The aceramic levels at Sesklo also contained bone fragments of domesticated cattle. The earliest similar occurrence documented in the Near East is at Çatalhöyük, in stratum VI, dating c. 5750 BC, although it might have been present in stratum XII too — c. 6100 BC.

The Neolithic settlement of Sesklo covered an area of approximately 20 hectares during its peak period at c. 5000 BC and comprised about 500 to 800 houses with a population estimated potentially, to be as large as 5,000 people.[3][4]

| c. 5000 BC | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 | |

| Historical Population of Sesklo | 1,000 — 5,000 | 781 | 857 | 906 | 970 |

The people of Sesklo built their villages on hillsides near fertile valleys, where they grew wheat and barley. They kept herds of mainly sheep and goats, although they also had cattle, swine, and dogs.

Their houses were small, with one or two rooms, built of wood or mudbrick in the early period. Construction techniques later became more homogeneous and all homes were built of adobe with stone foundations. The first houses with two levels were found and a clearly intentional urbanism existed. The lower levels of proto-Sesklo lack pottery, but the Sesklo people soon developed very fine-glazed earthenware that they decorated with geometric symbols in red or brown colors. New types of pottery were incorporated in the Sesklo period.

Images of the Sesklo archaeological site:

Megaron foundations

Megaron foundations View of Sesklo archaeological site

View of Sesklo archaeological site Remains of a building

Remains of a building

An "invasion theory" states that the Sesklo culture lasted more than one full millennium, until c. 5000 BC, when it was violently conquered by people of the Dimini culture. The Dimini culture in this theory is considered different from that found earlier at Sesklo, however, in a contrary theory by Professor Ioannis Lyritzis about the end of the unique Sesklo culture, he describes as the "Seskloans". He and R. Galloway compared ceramic materials from both Sesklo and Dimini using thermoluminescence dating methods. They discovered evidence that the inhabitants of the settlement in Dimini first appeared among the Seskloans c. 4800 BC, four centuries before the end of the Sesklo culture c. 4400 BC. Lyritzis concluded that the "Seskloans" and the "Diminians" co-existed for a period of time.

Ceramic decoration evolves to flame motifs toward the end of the Sesklo culture. Pottery of this "classic" Sesklo style also was used in Western Macedonia, as at Servia. That there are many similarities between the rare Asia Minor pottery and early Greek Neolithic pottery was acknowledged when investigations were made regarding whether these settlers could be migrants from Asia Minor, but such similarities seem to exist among all early pottery found in near eastern regions. The repertoire of shapes is not very different, but the Asia Minor vessels demonstrate significant differences.

They seem to be deeper than their Thessalian counterparts. Shallow, slightly open bowls are characteristic of the Sesklo culture, but are absent in Anatolian settlements. Use of a ring base was almost unknown in Anatolia, flat and plano-convex bases were worked instead. Altogether, the appearance of the vessels is different. The very rare examples of pottery from levels XII and XI at Çatalhöyük closely resemble the shape of the very coarse earthenware of Early Neolithic I from Sesklo, but the paste is significantly different, having a partly-vegetable temper, and this pottery is contemporaneous, not a predecessor, of the better-made products in the Thessalian material.

The earliest appearance of figurines is completely different as well. One significant characteristic of this culture is the abundance of statuettes of women, often pregnant, probably connected to widely hypothesized prehistoric fertility cults during the Paleolithic Period and the Neolithic Period. These sculptures of women are present in all the Balkan cultures and most of the Danube civilization throughout many millennia, although they may not be considered exclusive to this area. Archaeologist Marija Gimbutas even mentions recognition of a gorgon mask from the Sesklo culture,[5] an image that persisted throughout Ancient and Classical Greek arts.

._Archaeological_Museum_Athens.jpg) Monochrome bowls from Sesklo. Early Neolithic period (6500-5800 BC). Archaeological Museum Athens

Monochrome bowls from Sesklo. Early Neolithic period (6500-5800 BC). Archaeological Museum Athens Torso of woman with hands on chest, small terracotta, Sesklo culture, Neolithic, 6th–5th millennium BC

Torso of woman with hands on chest, small terracotta, Sesklo culture, Neolithic, 6th–5th millennium BC Female figurine, marble, Thessaly, 5300–3300 BC

Female figurine, marble, Thessaly, 5300–3300 BC Female figurine of a woman holding a baby, Sesklo, Neolithic, 4800–4500 BC

Female figurine of a woman holding a baby, Sesklo, Neolithic, 4800–4500 BC Sesklo culture

Sesklo culture

On the whole, the artifactual data argues in favor of a largely independent indigenous development of the Greek Neolithic settlements. The Sesklo culture is crucial in the expansion of the Neolithic into Europe. Dating and research points to the influence of Sesklo culture on both the Karanovo and Körös cultures that seem to originate there, and who in turn, gave rise to the important Danube civilization current.

See also

- Sesklo and Dimini fortifications

- Dimini

- Neolithic Greece

- Dispilio Tablet

- Dispilio Lakeside Neolithic Settlement Archaeological Collection

- Old Europe

- Vinča culture

- Vinča symbols

- Varna culture

- Hamangia culture

- Cucuteni–Trypillia culture

- Gumelniţa–Karanovo culture

- Butmir Culture

- Boian culture

- Tisza culture

- Linear Pottery culture

- Lengyel culture

- Funnelbeaker culture

- Starčevo culture

- Karanovo culture

Notes

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- Argissa-Magoula at the Wayback Machine (archived 2007-02-10)

- "History of Volos" on the web publication of the ESREA Life History and Biography Network's 2006 Conference Transitional Spaces, Transitional Processes and Research Volos, Greece, 2–5 March 2006.

- Curtis Neil Runnels, Priscilla Murray: Greece Before History: An Archaeological Companion and Guide. Stanford University Press, Stanford/CA 2001, p. 146: "Theocharis believed that the entire area from there to the upper acropolis of the site was filled with habitations and that Sesklo was a town of perhaps 5,000 people, rather than a village. Other archaeologists working at the site have reduced the population estimate to between 1,000 and 2,000, but either way, Sesklo was a settlement of impressive size in its day."

- Gimbutas 2001, p. 25.

References

- Liritzis, I (1981). Dating by thermoluminescence: Application to Neolithic settlement of Dimini. In: Anthropologika 2, 37–48 (in Greek with English summary).

- Liritzis, Y and Galloway, RB (1982). Thermoluminescence dating of Neolithic Sesklo and Dimini, Thessaly, Greece. In: PACT Journal 6, 450–459.

- Liritzis, Y and Dixon, J (1984). Cultural contacts between Neolithic settlements of Sesklo and Dimini, Thessaly. In: Anthropologika 5, 51–62 (in Greek, with complete English version sent on request).

- Reingruber, Agathe and Thissen, Laurens (2005). Aegean Catchment Aegean Catchment (E Greece, S Balkans and W Turkey) 10,000 – 5500 cal BC (paper on CANeW 14C databases and 14C charts).

External links

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 13, Table 1.1 "Chronology of the Ancient Near East". ISBN 9781134750917.

- Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428.

- Thorpe, I. J. (2003). The Origins of Agriculture in Europe. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 9781134620104.

- Price, T. Douglas (2000). Europe's First Farmers. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521665728.

- Jr, William H. Stiebing; Helft, Susan N. (2017). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781134880836.