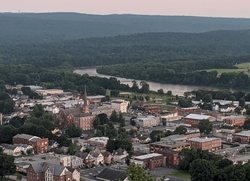

Port Jervis, New York

Port Jervis is a city located at the confluence of the Neversink and the Delaware rivers in western Orange County, New York, north of the Delaware Water Gap. Its population was 8,828 at the 2010 census. The communities of Deerpark, Huguenot, Sparrowbush, and Greenville are adjacent to Port Jervis. Matamoras, Pennsylvania is across the river and connected by bridge. Montague Township, New Jersey borders here.

Port Jervis | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

| Motto(s): Gateway to the Upper Delaware River | |

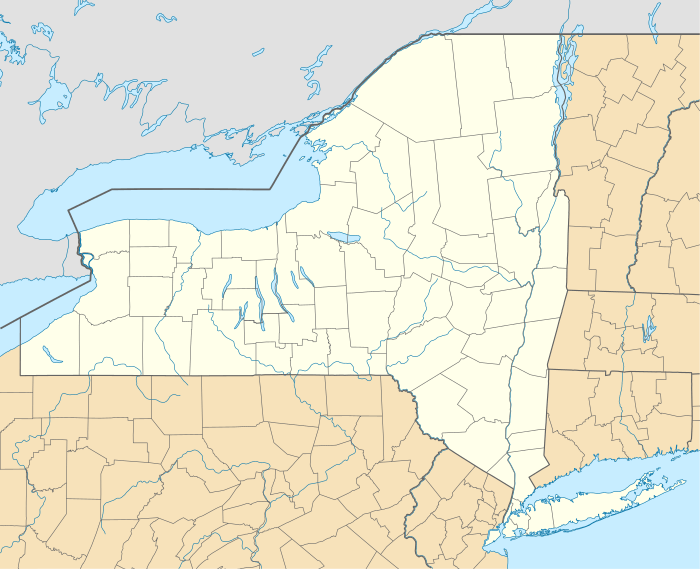

Location in Orange County and the state of New York. | |

Port Jervis Location in Orange County and the state of New York. | |

| Coordinates: 41°22′32″N 74°41′20″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Orange |

| Settled | 1690 |

| Village | 1853 |

| City | July 26, 1907 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Kelly Decker (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.70 sq mi (7.00 km2) |

| • Land | 2.53 sq mi (6.55 km2) |

| • Water | 0.17 sq mi (0.44 km2) 6.64% |

| Elevation | 400 ft (122 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 8,828 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 8,558 |

| • Density | 3,382.61/sq mi (1,306.12/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Postal code | 12771 |

| Area code | 845 Exchanges: 672,856,858 |

| FIPS code | 36-59388 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0960971 |

| Website | City of Port Jervis Website |

It was part of early industrial history, a point for shipping coal to major markets to the southeast by canal and later by railroads. Its residents had long-distance passenger service by railroad until 1970. The restructuring of railroads resulted in a decline in the city's business and economy.[3]

In the 21st century, from late spring to early fall, many thousands of travelers and tourists pass through Port Jervis on their way to enjoying rafting, kayaking, canoeing and other activities in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area and the Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River and the surrounding area.

Port Jervis is part of the Poughkeepsie–Newburgh–Middletown metropolitan area as well as the larger New York metropolitan area. In August 2008, Port Jervis was named one of "Ten Coolest Small Towns" by Budget Travel magazine.[4]

History

The first fully developed European settlement in the area was established by Dutch and English colonists c.1690, and a land grant of 1,200 acres (490 ha) was formalized on October 14, 1697. The settlement was originally known as Mahackamack, after a Lenape word. It was raided and burned in 1779 during the American Revolutionary War, by British and Mohawk forces under the command of Mohawk leader Joseph Brant before the Battle of Minisink. Over the next two decades, residents rebuilt the settlement. They developed more roadways to better connect Mahackamack with the eastern parts of Orange County.

After the Delaware and Hudson Canal was opened in 1828, providing transportation of coal from northeastern Pennsylvania to New York and New England via the Hudson River, trade attracted money and further development to the area.[5] A village was incorporated in 1853. It was renamed as Port Jervis in the mid-19th century, after John Bloomfield Jervis, chief engineer of the D&H Canal. Port Jervis grew steadily into the 1900s, and on July 26, 1907, it became a city.

Coming of the railroad

The first rail line to run through Port Jervis was the New York & Erie Railroad, which in 1832 was chartered to run from Piermont, New York, on the Hudson River in Rockland County, to Lake Erie. Ground was broken in 1835, but construction was delayed by a nationwide financial panic, and did not start again until 1838. The line was completed in 1851, and the first passenger train – with President Millard Fillmore and former United States Senator Daniel Webster on board – came through the city on May 14. The railroad went through a number of name changes, becoming the Erie Railroad in 1897.[6]

A second railroad, the Port Jervis and Monticello Railroad, later leased to the New York, Ontario and Western Railway (O&W), opened in 1868, running north out of the city, and eventually connecting to Kingston, New York, Weehawken, New Jersey and western connections.[6]

Like the D&H Canal, the railroads brought new prosperity to Port Jervis in the form of increased trade and investment in the community from the outside. However, the competition by the railroad, which could deliver products faster, hastened the decline of the canal, which ceased operation in 1898. The railroads were the basis of the city's economy for the coming decades. Port Jervis became Erie's division center between Jersey City, New Jersey and Susquehanna, Pennsylvania, and by 1922, twenty passenger trains went through the city every day. More than 2,500 Erie RR employees made their homes there.[7]

The railroads began to decline after the Great Depression.[7] A shift in transportation accelerated after World War II with the federal subsidy of the Interstate Highway System and increased competition from trucking companies. One of the first Class I railroads to shut down was the O&W, in 1957, leaving Port Jervis totally reliant on the Erie. A few years later, in 1960, the Erie, also on a shaky financial footing, merged with Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad to become the Erie Lackawanna. Railroad restructuring continued and in 1976, the Erie Lackawana became part of Conrail, along with a number of other struggling railroads, such as the Penn Central.[6] Since the breakup of Conrail, the trackage around Port Jervis has been controlled by Norfolk Southern. The decline of the railroads was an economic blow to Port Jervis. The city has struggled to find a new economic basis.

Racial incidents

On June 2, 1892, Robert Lewis, an African American, was lynched, hanged on Main Street in Port Jervis by a mob after being accused of participation in an assault on a white woman.[8][9] A grand jury indicted nine people for assault and rioting rather than Lewis's lynching.[10] Some literary critics think this event may have influenced Stephen Crane's 1898 novella The Monster. Crane lived in Port Jervis from 1878 until 1883 and frequently visited the area from 1891 to 1897.[11]

In the mid-1920s some residents in the area formed a Ku Klux Klan chapter, in the period of the KKK's early 20th-century revival. They burned crosses on Point Peter, the mountain peak that overlooks the city.[12]

Recent history

The city's location at the confluence of the Delaware and Neversink rivers has made it subject to occasional flooding. There was flooding during the 1955 Hurricane Diane, and a flood-related rumor started a panic in the population. This incident was studied and a 1958 report issued by the National Research Council: "The Effects of a Threatening Rumor on a Disaster-Stricken Community".[13]

In addition to the rivers having flooded during periods of heavy rainfall, at times ice jams have effectively dammed the Delaware, also causing flooding. In 1875 ice floes destroyed the bridge to Matamoras, Pennsylvania.[7] In 1981 a large ice floe resulted in the highest water crest measured to date at the National Weather Service's Matamoras river gauge 26.6 feet (8.1 m).[14]

Geography

Port Jervis is located on the north bank of the Delaware River at the confluence where: 1) the Neversink River – the Delaware's largest tributary – empties into the larger river. Port Jervis is connected by the Mid-Delaware Bridge across the Delaware to Matamoras, Pennsylvania.

From here the Delaware flows to the southwest, running parallel to Kittatinny Ridge until reaching the Delaware Water Gap. It heads southeast from there, continuing past New Hope, Pennsylvania and Lambertville, New Jersey; and the capital Trenton, New Jersey; to Philadelphia, and the Delaware Bay.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.7 square miles (7.0 km2), of which, 2.5 square miles (6.5 km2) is land and 0.2 square miles (0.52 km2) (6.64%) is water.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 6,377 | — | |

| 1880 | 8,678 | 36.1% | |

| 1890 | 9,327 | 7.5% | |

| 1900 | 9,385 | 0.6% | |

| 1910 | 9,564 | 1.9% | |

| 1920 | 10,171 | 6.3% | |

| 1930 | 10,243 | 0.7% | |

| 1940 | 9,749 | −4.8% | |

| 1950 | 9,372 | −3.9% | |

| 1960 | 9,268 | −1.1% | |

| 1970 | 8,852 | −4.5% | |

| 1980 | 8,699 | −1.7% | |

| 1990 | 9,060 | 4.1% | |

| 2000 | 8,860 | −2.2% | |

| 2010 | 8,828 | −0.4% | |

| Est. 2019 | 8,558 | [2] | −3.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[15] | |||

As of the census[16] of 2000, there were 8,860 people, 3,533 households, and 2,158 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,500/sq mi (1,300/km2). There were 3,851 housing units at an average density of 1,500/sq mi (590/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 82.4% White, 8.2% African American, 0.59% Native American, 0.64% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 2.19% from other races, and 2.26% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 7.5% of the population.

There were 3,533 households out of which 32.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.9% were married couples living together, 15.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.9% were non-families. 32.6% of all households were made up of individuals and 15.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 3.15.

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 27.8% under the age of 18, 8.4% from 18 to 24, 28.3% from 25 to 44, 20.3% from 45 to 64, and 15.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,241, and the median income for a family was $35,481. Males had a median income of $31,851 versus $22,274 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,525. About 14.2% of families and 15.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 25.5% of those under age 18 and 10.3% of those age 65 or over.

Points of interest

State line monuments

Port Jervis lies near the points where the states of New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania come together. South of the Laurel Grove Cemetery, under the viaduct for Interstate 84, are two monuments marking the boundaries between the three states.[18]

The larger monument is a granite pillar inscribed "Witness Monument". It is not on any boundary itself, but instead is a witness for two boundary points. On the north side (New York), it references the corner boundary point between New York and Pennsylvania that is located in the center of the Delaware River 475 feet (145 m) due west of the Tri-State Rock. On the south side (New Jersey), it references the Tri-State Rock 72.25 feet (22.02 m) to the south.

The smaller monument, the Tri-States Monument, also known as the Tri-State Rock, marks both the northwest end of the New Jersey and New York boundary and the north end of the New Jersey and Pennsylvania boundary.[19] It is a small granite block with inscribed lines marking the boundaries of the three states and a bronze National Geodetic Survey marker.[20] Both monuments were erected in 1882.[18]

Transportation

US 6, U.S. Route 209, New York State Route 42, and New York State Route 97 (the "Upper Delaware Scenic Byway"[21]) pass through Port Jervis. Interstate 84 passes to the south.

Port Jervis is the last stop on the 95-mile-long (153 km) Port Jervis Line, which is a commuter railroad service from Hoboken, New Jersey and New York City (via a Secaucus Transfer) that is contracted to NJ Transit by the Metro-North Railroad of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The track itself continues on to Binghamton and Buffalo, but passenger service west of Port Jervis was discontinued in November 1966.

Short Line provides bus service between Honesdale, Pennsylvania, Port Jervis, and the Port Authority Bus Terminal.[22]

Media

On July 4, 1953 WDLC at 1490 on the AM dial signed-on. Co-owned WDLC-FM (96.7) began operation in 1970, changing call letters to WTSX in 1984. In 2012, the call letters became WABT-FM. They also can receive WSPK-FM K104.7 and WRRV on 92.7.

Notable residents

Notable current and former residents of Port Jervis include:

- Frank Abbott, Mayor of Port Jervis from 1874 to 1876

- Ed Banach and Lou Banach, University of Iowa wrestlers, NCAA All Americans, and NCAA Tournament Champions, 1984 Summer Olympics wrestling gold medalists lived in Port Jervis and graduated from Port Jervis Senior High School.[23]

- Stephen Crane, author of The Red Badge of Courage, lived in Port Jervis between the ages 6–11 and frequently visited and wrote there from 1890 to early 1897.[24]

- William Howe Crane (1854–1926), older brother of Stephen Crane, lived and practiced law in Port Jervis for many years.

- Stefanie Dolson, basketball player for the Washington Mystics and formerly of the Connecticut Huskies Women's Basketball team, was born in Port Jervis. She was a high school standout at nearby Minisink Valley High School, where she was a McDonald's All-American and won multiple National Championships with Connecticut.

- Samuel Fowler (1851–1919) represented New Jersey's 4th congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1893–1895.[25]

- E. Arthur Gray (1925–2006) was the longest-serving mayor of Port Jervis and was later a New York State Senator. The Port Jervis United States Post Office building is dedicated to his name.[26]

- Benjamin Hafner (March 24, 1821 – Spring of 1899), known as "The Flying Dutchman" and "Uncle Ben", was an American locomotive engineer who worked for the Erie Railway.

- Bucky Harris, Baseball Hall of Famer born in Port Jervis.

- The Kalin Twins, Hal (1934–2005) and Herbie (1934–2006), were one hit wonders whose record "When" made the top 5 in the U.S. and was number one for five weeks in the U.K. in 1958.

- Amar'e Stoudemire (1982 – ), professional basketball player for the NY Knicks. Lived in Port Jervis for a duration of grade school and middle school. While living in Port Jervis he played Pop Warner Football and excelled at the sport. It is said that this is where he played basketball at local parks and first fell in love with the sport of basketball. He later moved to the state of Florida to live with his grandmother. Stoudemire then played high school basketball for six different schools, before graduating from Cypress Creek High School, and declaring for the NBA draft as a prep-to-pro player. In high school, Stoudemire won several honors most notably being selected as Mr. Basketball for the state of Florida. He was selected in the first round with the ninth overall pick in the 2002 NBA Draft by the Phoenix Suns and would spend eight seasons with them before signing with the New York Knicks.

Gallery

The E. Arthur Gray Post Office, on the NRHP

The E. Arthur Gray Post Office, on the NRHP The Free Library, a Carnegie library built in 1903

The Free Library, a Carnegie library built in 1903 The largest working rail turntable in the U.S. is in Port Jervis

The largest working rail turntable in the U.S. is in Port Jervis One of the many Victorian style houses in the city

One of the many Victorian style houses in the city Fort Decker (1793), the oldest building in the city

Fort Decker (1793), the oldest building in the city

References

- Notes

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Minisink Valley Historical Society - Port Jervis and the Gilded Age". minisink.org. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- Harrison, Karen Tina. "10 Coolest Small Towns: Port Jervis" Archived 2010-09-22 at the Wayback Machine. Budget Travel. (September 2008). Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- "D&H Canal & Gravity Railroad", Minisink Valley Historical Society

- "Railroads of Port Jervis". Minisink Valley Historical Society website

- "Port Jervis and the Gilded Age", Minisink Valley Historical Society

- "Lynching at Port Jervis. – Robert Jackson, a colored man, hanged by a mob" (PDF). New York Times. June 3, 1892.

- https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1025&context=ho_pubs

- "Port Jervis Lynching indictments" (PDF). New York Times. June 30, 1892.

- Wertheim, Stanley. A Stephen Crane Encyclopedia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1997. ISBN 0-313-29692-8. p. 195

- "Boys get 'K.K.K.' Warning – Port Jervis Youths are Ordered to restore crosses to Point Peter" (PDF). New York Times. August 13, 1922.

- "The Effects of a Threatening Rumor on a Disaster-Stricken Community ". National Research Council (NRC). (1958) Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- Weyandt, Kimberly. "Flooding is old news". The River Reporter (September 30 – October 6, 2004). Retrieved March 5, 2011.

However, the NWS' list of "Historical Crests" for the river at Matamoras/Port Jervis shows a peak of 25.5 feet (7.8 m) in 1904, and no record peak in 1981 at all. - "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- City of Port Jervis historical marker at the church site

- Graff, Bill (Summer 2006). "Sentinels at the Northern Border" (pdf). Unearthing New Jersey Vol. 2, No. 2. New Jersey Geological Survey.

- Vermeule, C. Clarkson (1888). "Physical Description of New Jersey: Northern Boundary Between New Jersey and New York". In Cook, George H. (ed.). Final Report of the State Geologist. 1. Trenton, New Jersey: Geological Survey of New Jersey. pp. 66–67.

- "LY2604: TRI STATES". U.S. National Geodetic Survey.

- "Upper Delaware Scenic Byway website Archived 2011-10-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Short Line bus schedules

- Rimer, Sara. "Port Jervis Celebrates Its Conquering Heroes", New York Times, September 3, 1984. Accessed October 10, 2007. "The Banach boys, as everyone knows them here, came back home this weekend, and as the townspeople celebrated their own Olympic gold medalists with a day of marching bands, waving flags and heartfelt speeches, all the hard times and disasters Port Jervis had endured seemed at last forgotten."

- Wertheim, Stanley and Paul Sorrentino. 1994. The Crane Log: A Documentary Life of Stephen Crane, 1871–1900. pp. 13-30, 54, 65, 71, 108, et al to 240, New York: G. K. Hall & Co. ISBN 0-8161-7292-7.

- Samuel Fowler, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed September 4, 2007.

- "E. Arthur Gray Post Office Building" in the Congressional Record (March 10, 2008)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Port Jervis, New York. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Port Jervis. |