Kiryas Joel, New York

Kiryas Joel (Yiddish: קרית יואל, Kiryas Yoyel, Yiddish pronunciation: [ˈkɪr.jəs ˈjɔɪ.əl], often locally abbreviated as KJ) is a village within the Town of Palm Tree in Orange County, New York, United States. The majority of its residents are Yiddish-speaking Hasidic Jews who belong to the worldwide Satmar Hasidic sect.

Kiryas Joel | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| |

| Nickname(s): KJ | |

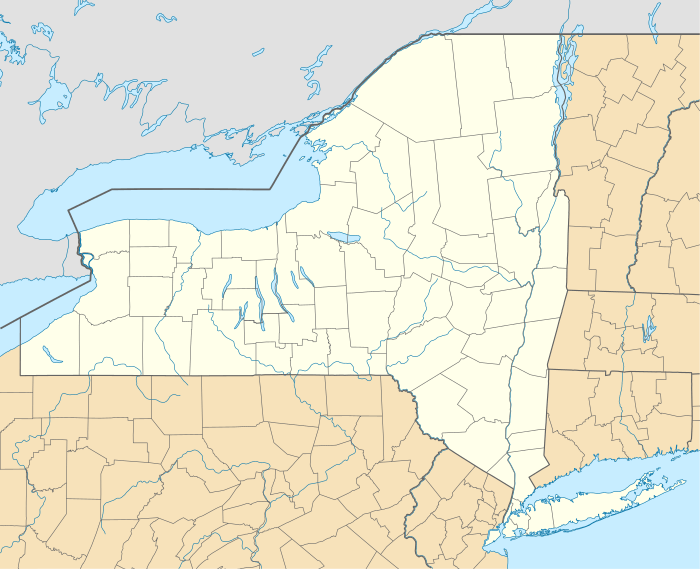

Location in Orange County and the state of New York. | |

Kiryas Joel Location within the state of New York  Kiryas Joel Location within the US | |

| Coordinates: 41°20′24″N 74°10′2″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Orange |

| Government | |

| • Administrator | Gedalye Szegedin |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.39 sq mi (3.61 km2) |

| • Land | 1.36 sq mi (3.53 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.08 km2) |

| Elevation | 842 ft (257 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 20,175 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 26,813 |

| • Density | 19,672.05/sq mi (7,593.95/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (US EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern Daylight Time) |

| Area code(s) | 845 Exchange: 492, 781, 782, 783 |

| FIPS code | 36-39853 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0979938 |

Kiryas Joel is part of the Poughkeepsie–Newburgh–Middletown, NY, Metropolitan Statistical Area, as well as the larger New York–Newark–Bridgeport, NY-NJ-CT-PA, Combined Statistical Area.

According to the Census Bureau's American Community Survey, Kiryas Joel has by far the youngest median age population of any municipality in the United States,[3] and the youngest, at 13.2 years old, of any population center of over 5,000 residents in the United States.[4] Residents of Kiryas Joel, like those of other Haredi Jewish communities, typically have large families, and this has driven rapid population growth.[5]

According to 2008 census figures, the village has the highest poverty rate in the nation. More than two-thirds of residents live below the federal poverty line, and 40% receive food stamps.[6] It is also the place in the United States with the highest percentage of people who reported Hungarian ancestry, as 18.9% of the population reported Hungarian descent in 2000.[7]

As of 2019, the village of Kiryas Joel separated from the town of Monroe, to become part of the town of Palm Tree.[8][9] On July 1, 2018, Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed a bill to create Palm Tree, triggering elections for the first governing board. The new town had 10 elected positions on the November 2018 ballot, including a supervisor, four council members, and two justices to preside over a town court.[10]

History

Kiryas Joel is named for the late Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum, the rebbe of Satmar and driving spirit behind the project. Rabbi Teitelbaum himself helped select the location a few years before his death in 1979. Rabbi Teitelbaum, originally from Hungary, was the rebbe who rebuilt the Satmar Hasidic dynasty in the years following World War II. The Satmar Hasidim who established Kiryas Joel came from Satu Mare, Romania, known when under Hungarian rule as Szatmár.[11]

In 1947, Rabbi Teitelbaum originally settled with his followers in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, a borough of New York City. By the 1970s, however, he decided to move the growing community to a location more secluded from the harmful influences and immorality of the outside world, while still close to the commercial center of New York. Rabbi Teitelbaum's choice was Monroe. The land for Kiryas Joel was purchased in the early 1970s, and fourteen Satmar families settled there in the summer of 1974. When he died in 1979, Teitelbaum was the first person to be buried in the town's cemetery. His funeral reportedly brought over 100,000 mourners to Kiryas Joel.[12]

It is widely believed that no candidates run for the village's board or the school board unless first approved by the grand rebbe, Rabbi Aaron Teitelbaum. In 2001, Kiryas Joel held a competitive election in which all candidates supported by the grand rebbe were re-elected by a 55–45% margin.[13]

Geography

Kiryas Joel is located at 41°20′24″N 74°10′02″W.[14]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 1.1 square miles (2.8 km2), and only a very small portion of the area (a small duck pond called "Forest Road Lake" in the center of the village) is covered with water.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1980 | 2,088 | — | |

| 1990 | 7,437 | 256.2% | |

| 2000 | 13,138 | 76.7% | |

| 2010 | 20,175 | 53.6% | |

| Est. 2019 | 26,813 | [2] | 32.9% |

| source:[15] | |||

| Largest ancestries (2000) | Percent |

|---|---|

| Hungarian | 18.9% |

| American | 8.0% |

| Israeli | 3.0% |

| Romanian | 2.0% |

| Polish | 1.0% |

| Czech | 0.3% |

| Russian | 0.3% |

| German | 0.2% |

| Languages (2010) [16][17] | Percent |

|---|---|

| Spoke Yiddish at home | 91.5% |

| Spoke only English at home | 6.3% |

| Spoke Hebrew at home | 2.3% |

| Spoke English "not well" or "not at all." | 46.0% |

Kiryas Joel began with a 1977 founding population of 500 people.[18] As of the census[19] of 2000, there were 13,138 people, 2,229 households, and 2,137 families residing in the village. The population density was 11,962.2 inhabitants per square mile (4,618.6/km2). There were 2,233 housing units, at an average density of 2,033.2 per square mile (785.0/km2). The racial make-up of the village was 99.02% White, 0.21% African American, 0.02% Asian, 0.12% from other races, and 0.63% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.93% of the population.

Kiryas Joel has the highest percentage of people who reported Hungarian ancestry in the United States, as 18.9% of the population reported Hungarian ancestry in 2000.[7] 3% of the residents of Kiryas Joel were Israeli, 2% Romanian, 1% Polish, and 1% European.[20]

The 2000 census also reported that 6.3% of village residents spoke only English at home, one of the lowest such percentages in the United States. 91.5% of residents spoke Yiddish at home, while 2.3% spoke Hebrew.[16] Of the Yiddish-speaking population in 2000, 46% spoke English "not well" or "not at all". Overall, including those who primarily spoke Hebrew and European languages, as well as primary Yiddish speakers, 46% of Kiryas Joel residents speak English "not well" or "not at all".[17]

There were 2,229 households, out of which 79.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 93.2% were married couples living together, 1.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 4.1% were non-families. 2.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 2.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 5.74, and the average family size was 5.84. In the village, the population was spread out with 57.5% under the age of 18, 17.2% from 18 to 24, 16.5% from 25 to 44, 7.2% from 45 to 64, and 1.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 15 years. For every 100 females, there were 116.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 118.0 males.

The village abides by strict Jewish customs, and its welcome sign asks visitors to dress conservatively and to "maintain gender separation in all public areas".[18]

Poverty and crime

The median income for a household in the village was $15,138, and the median income for a family was $15,372. Males had a median income of $25,043, versus $16,364 for females. The per capita income for the village was $4,355. About 61.7% of families and 62.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 63.9% of those under age 18 and 50.5% of those age 65 or over.

According to 2008 census figures, the village has the highest poverty rate in the nation, and the largest percentage of residents who receive food stamps. More than five-eighths of Kiryas Joel residents live below the federal poverty line, and more than 40 percent receive food stamps, according to the American Community Survey, a U.S. Census Bureau study of every place in the country with 20,000 residents or more.[6] A 2011 New York Times report noted that, despite the town's very high statistical poverty rates, "It has no slums or homeless people. No one who lives there is shabbily dressed or has to go hungry. Crime is virtually non-existent."[21] However, hundreds of incidents involving dissidents of the Grand Rebbe being stoned, their house and car windows broken, and their sidewalks stenciled with Hebrew profanities have been reported to the New York State Police.[22]

In November 2017, a local divorce mediator and an Israeli rabbi with ties to the village who were involved in the planning of a contract killing on an estranged husband were sentenced to prison.[23]

Transportation

Kiryas Joel has a very high rate of public transportation usage. Local transit within the area is operated by the Village of Kiryas Joel Bus System, a sub-section of Monsey Trails & Monroe Bus, who also feature service to Manhattan and to the heavily Haredi Jewish-populated Williamsburg and Borough Park sections of Brooklyn.[24]

Impact

Of growth

Friction with surrounding jurisdictions

The village has become a contentious issue in Orange County for several reasons, mainly related to its rapid growth.[25] Unlike most other small communities, it lacks a real downtown and much of it is given over to residential property, which has mostly taken the form of contemporary townhouse-style condominiums. New construction is ongoing throughout the community.

Population growth is strong. In 1990, there were 7,400 people in Kiryas Joel; in 2000, 13,100, nearly doubling the population. In 2005, the population had risen to 18,300.[25] The 2010 census showed a population of 20,175, for a population growth rate of 53.6% between 2000 and 2010, which was less than anticipated, as it was projected that the population would double in that time period.[26]

There are three religious tenets that drive our growth: our women don't use birth control, they get married young, and after they get married, they stay in Kiryas Joel and start a family. Our growth comes simply from the fact that our families have a lot of babies, and we need to build homes to respond to the needs of our community.

— Gedalye Szegedin, village administrator, quoted in "Reverberations of a Baby Boom" by Fernanda Santos, The New York Times, 2006[25]

Locally

The Town of Monroe also contains two other villages, Monroe and Harriman. Kiryas Joel's boundaries also come close to the neighboring towns of Blooming Grove and Woodbury.

Residents of these communities and local Orange County politicians view the village as encroaching on them.[25] Due to the rapid population growth occurring in Kiryas Joel, resulting almost entirely from the high birth rates of its Hasidic population, the village government has undertaken various annexation efforts to expand its area, to the dismay of the majority of the residents of the surrounding communities. Many of these area residents see the expansion of the high-density residential, commercial village as a threat to the quality of life in the surrounding suburban communities due to suburban sprawl. Other concerns of the surrounding communities are the impact on local aquifers and the projected increased volume of sewage reaching the county's sewerage treatment plants, already near capacity by 2005.

On August 11, 2006, residents of Woodbury voted by a 3-to-1 margin to incorporate much of the town as a village to constrain further annexation. Kiryas Joel has vigorously opposed such moves in court,[27] and even some Woodbury residents are concerned about adding another layer of taxation without any improved defense against annexations.

In March 2007, the village of Kiryas Joel sued the county to stop it from selling off 1 million US gallons (3,800 m3) of excess capacity at its sewage plant in Harriman. Two years prior, the county had sued the village to stop its plans to tap into New York City's Catskill Aqueduct, arguing that the village's environmental review for the project had inadequately addressed concerns about the additional wastewater it would generate. The village is appealing an early ruling which sided with the county.[28]

In its action, Kiryas Joel accuses the county of inconsistently claiming limited capacity in its suit when it is selling the million gallons to three communities outside its sewer district.

In 2017, the village proposed to settle a lawsuit over some additional annexations it had proposed by petitioning the county legislature to allow it to become the county's 21st town. It would be named Palm Tree, after the English translation of Teitelbaum's name. In return for the village dropping its request to annex 507 acres (205 ha), United Monroe and Preserve Hudson Valley, the plaintiffs, agreed to withdraw their appeal of a decision allowing the annexation of a 164-acre (66 ha) parcel. The new town would also be prohibited from filing annexation proposals or encouraging the creation of new villages for 10 years. Two-thirds of the county legislature must approve the creation of the new town, and a vote of Monroe residents may also be required.[29] The referendum passed on November 7, 2017.[30]

Local politics

Critics of the village cite its impact on local politics. Villagers are perceived as voting in a solid bloc. While this is not always the case, the highly concentrated population often does skew strongly toward one candidate or the other in local elections, making Kiryas Joel a heavily courted swing vote for whichever politician offers Kiryas Joel the most favorable environment for continued growth. In the hotly contested 2013 Town Supervisors race, the Kiryas Joel bloc vote elected Harley Doles to the position of town supervisor. Kiryas Joel then sought to annex 510 acres (210 ha) of land into their village and the new Monroe Town Board has had no comment on this issue. In late 2014 village leadership proposed alternatively that a new village, to be called Gilios Kiryas Joel, be created on the 1,140 acres (460 ha) south of the village within Monroe, including all the land it had wanted to annex.[31]

Kiryas Joel played a major role in the 2006 Congressional election. The village was at that time in the congressional district represented by Republican Sue Kelly. Village residents had been loyal to Kelly in the past, but in 2006, voters were upset over what they saw as lack of adequate representation from Kelly for the village. In a bloc, Kiryas Joel swung around 2,900 votes to Kelly's Democratic opponent, John Hall. The vote in Kiryas Joel was one reason Hall carried the election, which he did by 4,800 votes.

Internal friction

Joel Teitelbaum had no son, and thus no clear successor. His nephew, Moses, was appointed by the community's committee members. But not all Satmar accepted Moses as the community leader, and even some of those that did questioned some of his actions and pronouncements. He responded by running the village in what they called an autocratic manner, through his deputy, Abraham Weider, who also served as mayor and president of the school board, as well as the main synagogue and yeshiva in the village.[22]

In 1989, the village forbade any property owner from selling or renting an apartment without its permission. Teitelbaum elaborated that "anyone that rents without this permission has to be dealt with like a real murderer ... and he should be torn out from the roots."[32]

In the early 1990s New York State Police responded many times to the village, which has a generally low crime rate otherwise, when self-described dissidents reported harassment such as broken windows and graffiti of Hebrew profanity on their property. In one incident, troopers rode a school bus undercover to catch teenage boys stoning it; the boys later stoned a backup police cruiser when it arrived. One of Weider's nephews was among those arrested. He admitted that some of the village's young men took it upon themselves to act violently against dissidents because they could not bear to hear the grand rebbe criticized, although he said most of them were provoked to do so by dissidents.[22]

"Someone not following breaks down the whole system of being able to educate and being able to bring up our children with strong family values," Weider told The New York Times in 1992. "Why do you think we have no drugs? If we lost respect for the Grand Rabbi, we lose the whole thing."[22]

In January 1990 the village held its first and, for a decade, only school board election. "It's like this," Teitelbaum explained when he announced the names of seven handpicked candidates. "With the power of the Torah, I am here the authority in the rabbinical leadership ... As you know I want to nominate seven people and I want these people to be the people."[32]

One dissident, Joseph Waldman, decided nevertheless to run on his own. He was made unwelcome at the synagogue, his children expelled from yeshiva, his car's tires slashed and his windows broken. Several hundred residents marched in the streets in front of his house chanting "Death to Joseph Waldman!" after posters calling for that fate were posted in the synagogue. After the election, in which Waldman finished last but still won 673 votes, 60 families who were known to have voted for him were barred from visiting their fathers' graves in the village cemetery that was owned by the rabbi and banned from the synagogue (also, at the time, the village's only polling place). Waldman compared Teitelbaum to Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini.[32]

After the election, a state court ruled that Waldman's children had to be reinstated at the yeshiva, an action that was only taken after the judge held Teitelbaum in contempt and fined him personally. Friction continued as some of the dissidents banned from the synagogue circulated a petition calling for the polls to be moved to a neutral location. It originally drew 150 signatures, but all but 15 retracted their names after being threatened with excommunication by the grand rabbi, signing a document that they had not actually read the petition. One of the dissidents who signed was attacked while praying, and state troopers had to be called in again to disperse a mob that gathered on Waldman's lawn and broke his windows.[22]

Electoral fraud allegations

On four occasions since 1990, the Middletown Times-Herald Record has run lengthy investigative articles on claims of electoral fraud in the village. A 1996 article found that Kiryas Joel residents who were students at yeshivas in Brooklyn had on many occasions apparently registered and voted in both the village and Brooklyn;[33] a year later the paper reported that it had happened again. In 2001 absentee ballots were apparently cast by voters who did not normally reside in the village. In some cases, ballots were cast by people who seemed to reside in Antwerp, Belgium, without a set date of expected return and thus would not be allowed under New York law to vote in any election for state or local office. That article led to a county grand jury investigation in 2001, which concluded that while procedures were not followed and many mistakes were made, there was no evidence of deliberate intent to violate the law.[34]

Before the 2013 Republican primary in that year's special election for the state assembly seat vacated by Annie Rabbitt, later elected county clerk, members of United Monroe, a local group that organizes and coordinates political opposition to the village and those local officials it believes support it, asked the county's Board of Elections to assign them to Kiryas Joel as election inspectors, who verify that voters are registered before allowing them to vote. The board's Democratic commissioner, Sue Bahrens, initially agreed to appoint six to serve in the village, but later reversed that decision. The six sued the county, alleging religious discrimination; it responded that they had no standing to sue. Village Manager Gedalye Szegedin said the citizens were entitled to have inspectors who spoke Yiddish and understood their culture and customs. A state court justice dismissed the discrimination claim but ruled that the United Monroe inspectors had been dismissed arbitrarily and capriciously and were entitled to their appointments, but did not say when or where.[34]

In 2014, the newspaper examined claims by poll watchers from United Monroe that they were intimidated and harassed by other poll watchers sympathetic to the village government when they tried to challenge voters whose signatures did not initially appear to match those on file during the previous year's elections for county offices. They further alleged that election inspectors in the polling place, a banquet hall where 6,000 residents voted, sometimes gave the voters ballots before the signatures could be checked.[34]

Some of the United Monroe poll watchers claimed that Langdon Chapman, an attorney for the Monroe town board, which they believe is controlled by members deferential to Kiryas Joel and its interests, was one of those who intimidated them. Coleman told the Record that while he had been at the banquet hall in question, he had only insisted that poll watchers state the reason for their challenges, as legally required, and had left after two hours. He was subsequently appointed county attorney (the lawyer who represents the county in civil matters) by new county executive Steve Neuhaus, whose margin of victory included all but 20 of the votes from the village.[34]

After the election, United Monroe members found over 800 voters in Kiryas Joel whose signatures did not match those on file, in addition to 25 they had challenged at the polls, three of whom were later investigated by the county sheriff; the rest were considered unfounded. Orange County District Attorney David Hoovler, elected along with Neuhaus, told the newspaper it was difficult to investigate the allegations since they could not verify the identity of either signer, if in fact there were two. The Record attempted to contact some of those voters; the only one they reached hung up when asked about the election.[34]

Large families

Women in Kiryas Joel usually stop working outside the home after the birth of a second child.[25] Most families have only one income and many children. The resulting poverty rate makes a disproportionate number of families in Kiryas Joel eligible for welfare benefits, when compared to the rest of the county. The New York Times wrote,

Because of the sheer size of the families (the average household here has six people, but it is not uncommon for couples to have 8 or 10 children), and because a vast majority of households subsist on only one salary, 62 percent of the local families live below poverty level and rely heavily on public assistance [government welfare], which is another sore point among those who live in neighboring communities.[25]

A 60-bed post-natal maternal care center was built, with $10 million in state and federal grants. Mothers can recuperate there for two weeks away from their large families.[35]

Hepatitis A & vaccine trial

In the 1990s, the first clinical trials for the hepatitis A vaccine took place in Kiryas Joel, where 70 percent of residents had been affected. This disproportionate rate of hepatitis A infection was due in part to Kiryas Joel's high birth rate and crowded conditions among children, who bathed together in pools and ate from communal food at school. Children who were not infected with hepatitis A were separated into two groups, one receiving the experimental vaccine and the other receiving a placebo injection. Based on this study, the vaccine was declared 100 percent effective. Merck licensed the vaccine in 1995, and it became available in 1996, after which the hepatitis A infection rate fell by 75 percent in the United States.[36]

Litigation

The unusual lifestyle and growth pattern of Kiryas Joel has led to litigation on a number of fronts. In 1994, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School District v. Grumet that the Kiryas Joel school district, which covered only the village, was designed in violation of the Establishment Clause of the 1st Amendment, because the design accommodated one group on the basis of religious affiliation.[37] Subsequently, the New York State Legislature established a similar school district in the village that has passed legal muster.[38] Further litigation has resulted over what entity should pay for the education of children with disabilities in Kiryas Joel, and over whether the community's boys must ride buses driven by women.[25] A case against the village is currently pending in federal district court; plaintiffs, who are asking for the village to be dissolved, say that Kiryas Joel is a theocracy whose existence violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, where local government leaders abuse the laws, such as those for tax-exempt status, zoning, and sanitation, to favor members of their own sect and persecute other Orthodox Jews. They also say that the leaders commit vote fraud by intimidating dissident voters and busing in non-residents.[39]

Kiryas Joel's public school district has long been a subject of controversy. First created in 1990 by an act of the New York State Legislature to serve special education students in the almost entirely Hasidic Orange County village, the specifically carved-out district weathered a series of constitutional challenges. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1994 that the district violated the Constitution's requirement of separation between religion and state. But the state government rewrote the law allowing for creation of the district, finally finding statutory language able to overcome the constitutional barriers.

According to NYSED documents, the district served 123 students in the 2008–2009 school year, and 217 students the previous year, all of them under special education.

See also

- New Square, New York − an all-Hasidic village in a neighboring county.

- Kaser, New York − an all-Hasidic village in a neighboring county.

- Kiryas Tosh, Quebec – an all-Hasidic community in Quebec.

- Qırmızı Qəsəbə

- Shtetl

References

Notes

- On the top sign, the Yiddish reads, "Kiryas Joel Bus Transportation Bus Stop"; on the bottom, "Village Bus Stop".

Footnotes

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Here's The Youngest Town In Every State Archived 2014-09-12 at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 11, 2014.

- City Data Archived 2006-01-15 at the Wayback Machine Accessed December 14, 2006.

- "Neighbors riled as insular Hasidic village seeks to expand". The Korea Times. February 27, 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-03-05. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- "KJ highest US poverty rate, census says" Archived 2018-07-04 at the Wayback Machine, Matt King, Times Herald-Record, January 30, 2009.

- "Hungarian Ancestry Search - Hungarian Genealogy by City - ePodunk.com". epodunk.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Oster, Marcy, "Town of Palm Tree becomes first official U.S. Haredi Orthodox town", January 6, 2019, https://www.clevelandjewishnews.com/news/national_news/town-of-palm-tree-becomes-first-official-u-s-haredi/article_11c6aee2-e1bc-5370-8942-e70ff2de33e0.html Archived 2019-01-08 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- Foderaro, Lisa (November 20, 2017). "Call It Splitsville, N.Y.: Hasidic Enclave to Get Its Own Town". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2017-11-20. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- McKenna, Chris. "Cuomo signs bill to start Town of Palm Tree in 2019". recordonline.com. Archived from the original on 2018-07-02. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- Mintz, Jerome R., Hasidic People. A Place in the New World. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press 1992, pp. 28. ISBN 0-674-38115-7

- "Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum Dies at 92, Leader of the Satmar Hasidic Sect" Archived 2018-07-23 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, August 20, 1979. Accessed May 27, 2018.

- "A Hasidic Village Gets a Lesson In Bare-Knuckled Politicking" Archived 2009-02-04 at the Wayback Machine by David W. Chen, The New York Times, June 9, 2001. Accessed December 14, 2006.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "CENSUS OF POPULATION AND HOUSING (1790–2000)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-12-14.

- Modern Language Association Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine base data on Kiryas Joel. Accessed online December 14, 2006.

- Modern Language Association Archived 2009-02-03 at the Wayback Machine English proficiency in Kiryas Joel. Accessed online December 14, 2006.

- "Hasidic Jews in upstate New York: Monroe's referendum and a peculiar population boom". The Economist. 2 November 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-11-03. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Kiryas Joel, NY, Ancestry & Family History". Epodunk.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

-

2=Sam Roberts (April 21, 2011). "A Village With the Numbers, Not the Image, of the Poorest Place". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2014-04-14. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

The poorest place in the United States is not a dusty Texas border town, a hollow in Appalachia, a remote Indian reservation, or a blighted urban neighborhood. It has no slums or homeless people. No one who lives there is shabbily dressed or has to go hungry. Crime is virtually non-existent.

- Winerip, Michael (September 20, 1992). "Pious Village Is No Stranger To the Police". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-05-26. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- Gajanan, Mahita (September 7, 2016). "Rabbi and Orthodox Jewish Man Plotted to Kidnap and Murder Husband to Get Divorce for his Wife, Officials Say" Archived 2016-11-14 at the Wayback Machine, Time

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-03. Retrieved 2013-10-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Reverberations of a Baby Boom" Archived 2017-12-25 at the Wayback Machine by Fernanda Santos, The New York Times, August 27, 2006, retrieved August 27, 2006; accessed online in fee-based archive at same URL December 13, 2006.

- "Census 2010: Orange population growth rate 2nd highest in state, but lower than expected" Archived 2017-08-16 at the Wayback Machine by Chris Mckenna, Times Herald-Record, March 25, 2011. Accessed December 7, 2011 In 2006, village administrator Gedalye Szegedin stated:

- McKenna, Chris (August 3, 2006). "KJ tries to stop village vote". Times Herald-Record. Middletown, New York: Orange County Publications. Archived from the original on 2011-12-08. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- McKenna, Chris; March 6, 2007; "Kiryas Joel sues county over sewage Archived 2016-09-14 at the Wayback Machine"; Times-Herald Record; retrieved March 6, 2007.

- "Deal to create Town of Palm Tree to go before Orange County legislators, maybe Monroe voters". Mid-Hudson News. July 20, 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-11-08. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-11-08. Retrieved 2017-11-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- McKenna, Chris (November 19, 2014). "Kiryas Joel may propose new village". Times-Herald Record. Archived from the original on 2014-12-06. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- Rosen, Jeffrey (April 11, 1994). "Village People". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 2015-09-15. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- Greenberg, Eric (October 4, 1996). "New York state investigates voter fraud among Satmar". 6=New York Jewish Week. Archived from the original on 2014-12-06. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- McKenna, Chris (October 26, 2014). "Inside the Kiryas Joel voting machine". Times-Herald Record. Archived from the original on 2014-12-06. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- "Again: Hasidic Village Kiryas Joel Poorest Place In US - FailedMessiah.com". typepad.com. Archived from the original on 2015-07-25. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "STD Awareness: Viral Hepatitis". advocatesaz.org. 22 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2017-09-26. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- 512 U.S. 687 (1994).

- "Controversy Over, Enclave Joins School Board Group Archived 2009-02-04 at the Wayback Machine" by Tamar Lewin, The New York Times, April 20, 2002.

- Fitzgerald, Jim (June 13, 2011). "Dissident Jews say enclave in NY oppresses them". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2013-11-28. Retrieved 2014-09-14.

Further reading

- Hasidic Public School Loses Again Before U.S. Supreme Court, but Supporters Persist (The New York Times, 1999)

- Kiryas Joel Ranks at Top of National List of Municipalities that Lobby the Federal Government (Center for Responsive Politics' Capital Eye Blog, September 2009)

- 2006 Census

- DAN LEVIN (December 16, 2007). "A Display of Disapproval That Turned Menacing". The New York Times.

- Grumet, L., & Caher, J. M. (2016). The Curious Case of Kiryas Joel: The Rise of a Village Theocracy and the Battle to Defend the Separation of Church and State. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.