Pittsfordipterus

Pittsfordipterus ("wing from Pittsford") is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Pittsfordipterus is classified as part of the family Adelophthalmidae, the only clade in the derived ("advanced") Adelophthalmoidea superfamily of eurypterids. Fossils of the single and type species, P. phelpsae, have been discovered in deposits of Silurian age in Pittsford, New York state. The genus is named after Pittsford, where the two only known specimens have been found.

| Pittsfordipterus | |

|---|---|

| |

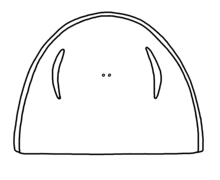

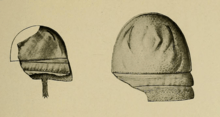

| Restoration of the carapace of P. phelpsae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Superfamily: | †Adelophthalmoidea |

| Family: | †Adelophthalmidae |

| Genus: | †Pittsfordipterus Kjellesvig-Waering & Leutze, 1966 |

| Type species | |

| †Pittsfordipterus phelpsae Ruedemann, 1921 | |

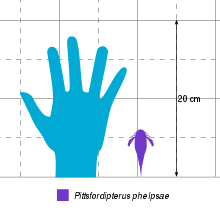

Pittsfordipterus was a basal ("primitive") genus that was distinguished from the more derived adelophthalmids by the specialization of its genital operculum (a plate-like segment which contains the genital aperture) and its long and narrow eyes, being Bassipterus' closest relative. With an estimated length of 6 cm (2.4 in), Pittsfordipterus was one of the smallest adelophthalmids.

Description

Like the other adelophthalmid eurypterids, Pittsfordipterus was a small eurypterid. The total size of the largest known specimen is estimated at only 6 cm (2.4 in), making it one of the smallest adelopththalmids and eurypterids overall.[1]

Pittsfordipterus had a broad carapace (dorsal shield of the head) with elongated and narrow eyes placed away from the head margin.[2] In the largest specimen (the paratype), the carapace was 18 mm (0.7 in) wide and 13 mm (0.5 in) long. Five parallel lines along the front margin that make up the ornamentation can be seen on the surface of the carapace. In the posterior portion, a series of small irregularly distributed tubercles (rounded protuberances) appear. In the posterior margin, there is a strip of fine triangular scales. The tergites (the dorsal part of the body segments) also present three to four parallel lines along the posterior margin, followed by five lines that end in a series of separate and lunate (crescent-shaped) scales.[3]

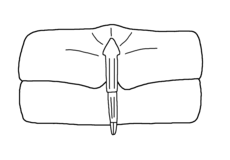

Its genital operculum (a plate-like segment which contains the genital aperture) is the main characteristic that distinguishes it from the rest of the derived (more "advanced") adelopththalmids, showing characteristics indicative of the more basal eurypterid Eurypterus. It possessed two opercular flaps, two protruding extensions lateral to the genital appendage. The genital appendage (which is of type A, assumed to represent females) had a great length, extending beyond the second abdominal plate. It was divided into two joints. The first was approximately hastate (with protruding lobes) and was ornamented with fine scales. It was followed by a tubular (tube-shaped) joint that lacked ornamentation. The second joint was less broad and long. The distal end (the farthest from the junction point) widens, with a pair of sharp lateral projections ("protuberances"). This gives it a termination finished in three spines similar to those that occur in the genital appendage (of type A) in Slimonia and Adelophthalmus. The American paleontologist Erik Norman Kjellesvig-Waering predicted that the genital operculum would end up being a feature of great phylogenetic importance at least at the generic level.[4]

History of research

Pittsfordipterus is only known by two well preserved specimens, the holotype and paratype (NYSM 10102 and NYSM 10103, both at the New York State Museum).[5] In 1921, the American paleontologist Rudolf Ruedemann described the species Hughmilleria phelpsae from the Vernon Formation of the New York state. Ruedemann noted several differences between his new species and H. socialis (type species of Hughmilleria), including the size of the carapace (broader and shorter than in the latter), the position of the eyes further from the margin (as opposed to the marginal position of H. socialis) and the morphology of the genital appendage. Instead, Ruedemann suggested a relationship between H. phelpsae and the species H. shawangunk based on the size of the carapace and the position of the eyes more or less being similar, as well as the same linear ornamentation. However, while in its ventral part, H. shawangunk had the same linear ornamentation, H. phelpsae had imbricate scales similar to those of H. socialis. Even so, he suggested that H. phelpsae could probably represent a late descendant of H. shawangunk.[3]

In the description of the genus Parahughmilleria in 1961, Kjellesvig-Waering suggested that H. phelpsae should be classified under this new genus.[6] Three years later, Kjellesvig-Waering decided to assign the same species to the subgenus Nanahughmilleria.[4] In 1966, Kjellesvig-Waering, together with the American paleontologist Kenneth Edward Caster, recognized that H. (N.) phelpsae was sufficiently different from the other eurypterids and erected the genus Pittsfordipterus based on the morphology of its genital appendage.[7] The name Pittsfordipterus is translated as "wing from Pittsford", with the first word of the name referring to the type locality (the location where it was initially found) and the last word composed of the Greek word πτερόν (pteron, wing).[8]

Classification

Pittsfordipterus is classified as part of the family Adelophthalmidae, the only clade ("group") within the superfamily Adelophthalmoidea.[9] P. phelpsae was originally described as a species of the genus Hughmilleria, but it was considered different enough to represent a new separate genus in 1966.[7]

In 2004, O. Erik Tetlie erected the family Nanahughmilleridae in an unpublished thesis to contain the adelophthalmoids with no or reduced genital spatulae (a long, flat piece in the operculum) and the second to fifth pair of prosomal (of the prosoma, "head") appendages (limbs) of Hughmilleria-type (hypothetical since the appendages of Pittsfordipterus are unknown). This family contained Nanahughmileria, Pittsfordipterus and perhaps Parahughmilleria.[5] However, the clade has almost never been used in subsequent studies and lists of eurypterids,[10] and instead, they classify the nanahughmillerids as part of Adelophthalmidae.[9] A derived clade in which Nanahughmilleria is closest to Parahughmilleria and Adelopththalmus is better supported, as well as a basal (more "primitive") group consisting of Pittsfordipterus and Bassipterus. This clade is backed by a pair of synapomorphies (shared characteristics different from that of their latest common ancestor), relatively long and narrow eyes and a complex termination of the genital appendage. Therefore, Pittsfordipterus is the sister group (closest relative) of Bassipterus.[2]

The cladogram below presents the inferred phylogenetic positions of most of the genera included in the three most derived superfamilies of the Diploperculata infraorder of eurypterids (Adelophthalmoidea, Pterygotioidea and the waeringopteroids), as inferred by Odd Erik Tetlie and Markus Poschmann in 2008, based on the results of a 2008 analysis specifically pertaining to the Adelophthalmoidea and a preceding 2004 analysis.[2]

| Diploperculata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

Pittsfordipterus fossils have been recovered from Silurian deposits of the Late Ludlow (Ludfordian) epoch of the Vernon Formation of the New York state.[1][3] In this formation, fossils of other eurypterids have been found, such as Eurypterus pittsfordensis or Mixopterus multispinosus, as well as indeterminate species of phyllocarids, leperditiids and cephalopods. The lithology of the place consists of dark gray to black shale with abundant gypsum and dolomite slabs that reach a combined thickness of 305 m (1,000 ft). It is also possible to find green shale and very rarely, red shale. This habitat was probably lagoonal.[11][3]

References

- Lamsdell, James C.; Braddy, Simon J. (2009-10-14). "Cope's Rule and Romer's theory: patterns of diversity and gigantism in eurypterids and Palaeozoic vertebrates". Biology Letters: rsbl20090700. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0700. ISSN 1744-9561. PMID 19828493. Supplementary information Archived 2018-02-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Erik Tetlie, O; Poschmann, Markus (2008-06-01). "Phylogeny and palaeoecology of the Adelophthalmoidea (Arthropoda; Chelicerata; Eurypterida)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (2): 237–249. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002416.

- Ruedemann, Rudolf (1921). "A recurrent Pittsford (Salina) fauna". New York State Museum Bulletin: 205–222.

- Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1964). "Eurypterida: Notes on the Subgenus Hughmilleria (Nanahughmilleria) from the Silurian of New York". Journal of Paleontology. 38 (2): 410–412. JSTOR 1301566.

- Tetlie, Odd Erik (2004). Eurypterid phylogeny with remarks on the origin of arachnids (PhD). University of Bristol. pp. 1–344.

- Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1961). "The Silurian Eurypterida of the Welsh Borderland". Journal of Paleontology. 35 (4): 789–835. JSTOR 1301214.

- Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N.; Leutze, Willard P. (1966). "Eurypterids from the Silurian of West Virginia". Journal of Paleontology. 40 (5): 1109–1122. JSTOR 1301985.

- Meaning of pterus. www.wiktionary.org.

- Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2018. A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives. In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern.

- Tetlie, O.E.; van Roy, P. (2006). "A reappraisal of Eurypterus dumonti Stainier, 1917 and its position within the Adelophthalmidae Tollerton, 1989" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique. 76: 79–90.

- "Eurypterid-Associated Biota of the Vernon Formation, Pittsford, New York (Silurian of the United States)". The Paleobiology Database.