Eysyslopterus

Eysyslopterus is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Eysyslopterus is classified as part of the family Adelophthalmidae, the only clade within the derived ("advanced") Adelophthalmoidea superfamily of eurypterids. One fossil of the single and type species, E. patteni, has been discovered in deposits of the Late Silurian period (Ludlow epoch) in Saaremaa, Estonia. The genus is named after Eysysla, the Viking name for Saaremaa, and opterus, a traditional suffix for the eurypterid genera, meaning "wing". The species name honors William Patten, an American biologist and zoologist who discovered the only known fossil of Eysyslopterus.

| Eysyslopterus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Restoration of the carapace of E. patteni based on Tetlie and Poschmann's of 2008 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Superfamily: | †Adelophthalmoidea |

| Family: | †Adelophthalmidae |

| Genus: | †Eysyslopterus Tetlie & Poschmann, 2008 |

| Type species | |

| †Eysyslopterus patteni Størmer, 1934 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

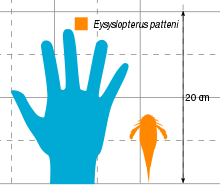

Eysyslopterus is a little-known basal genus that was distinguished from the rest of adelophthalmids by the position near the head margin of the eyes, different from the rest of its relatives. Its carapace was parabolic (approximately U-shaped) and with transverse deep furrows forming the ornamentation. With an estimated length of 8 cm (3.1 in), Eysyslopterus was a small eurypterid. It lived in a nearshore lagoonal quiet community along other eurypterid species.

Description

Like the other adelophthalmid eurypterids, Eysyslopterus was a small eurypterid. The total size of the only known specimen is estimated at only 8 centimetres (3.1 inches),[1] far from the largest adelophthalmids like Adelophthalmus khakassicus of 32 cm (12.6 in) in length.[2]

Eysyslopterus is a little known eurypterid, with only one specimen collected that only preserves the prosoma ("head") with no appendages (limbs). The prosoma was rather broad, with a parabolic (approximately U-shaped) outline. It was 19.5 millimetres (0.77 in) long and 22 mm (0.87 in) wide. Although the anterior part of the prosoma is not preserved, the fossil mold indicates a pointed portion. The posterior border was slightly convex. A narrow rim surrounded the lateral margins of the carapace (dorsal shield of the prosoma). The prosoma surface was gently arched, with the central portion rather level. The eyes were reniform (bean-shaped) and with a thin and light-colored test (external "shield") on its surface. They measured 4.5 mm (0.18 in) in length. The ocelli (simple eyes) were located in the posterior half of the prosoma and consisted of two circular spots. The posterior part was smooth, but the previous part had a distinctive ornamentation. This ornamentation extended until the end of the eyes and was composed of transverse lines developed as deep furrows.[3]

Eysyslopterus was a basal ("primitive") genus with respect to the rest of adelophthalmids, with the eyes closer to the margin than to the ocelli, suggesting that the eyes migrated towards a central position from the basal genera to Adelophthalmus.[4]

History of research

.png)

Eysyslopterus is only known from one single specimen (and is therefore the holotype, AMNH 32720, housed at the American Museum of Natural History) which preserves the carapace.[4] This fossil was collected by the American biologist and zoologist William Patten during his extensive explorations at the Rootsikula Formation in Saaremaa, Estonia (then part of the Soviet Union). During a meeting between Patten and the Norwegian paleontologist and geologist Leif Størmer in 1932, Størmer observed Patten's private collection of eurypterids, among which he recognized a carapace of a new unknown species. He described it in 1934 as belonging to the genus Hughmilleria patteni, named after Patten, who died months after the meeting. Størmer noticed several differences between his new species and other Hughmilleria species, essentially the shape of the prosoma and the form or position of the eyes. He also suggested a close relationship between H. patteni and other species, especially the Scottish species H. lanceolata.[3]

However, in 1961, the American paleontologist Erik Norman Kjellesvig-Waering split Hughmilleria in two subgenera, H. (Hughmilleria) for species with large ovoid marginal eyes and H. (Nanahughmilleria) for small reniform intramarginal (within the margin) eyes. Since H. patteni fulfilled this condition, it was referred to H. (Nanahughmilleria).[5] It was not until 2008 when during a phylogenetic review of the entire Adelophthalmidae family by the Norwegian Odd Erik Tetlie and German Markus Poschmann paleontologists, N. patteni was recognized as sufficiently different to represent its own genus due to the anterior position of its eyes, much more exaggerated than in the other adelophthalmid genera. The first part of the generic name is composed of the word Eysysla, the Viking name for Saaremaa, and the second part by opterus, a suffix commonly used in eurypterids which means "wing" (and therefore, translated as "wing of Eysysla").[4]

Classification

Eysyslopterus is classified as part of the family Adelophthalmidae, the only clade ("group") within the superfamily Adelophthalmoidea.[6] E. patteni was originally described as a species of the genus Hughmilleria,[3] but it was considered different enough to represent a new separate genus in 2008.[4]

Eysyslopterus is considered to be the most basal adelophthalmid genus due to the position of its eyes. These are placed closer to the margin than to the ocelli, in contrast to any other adelopthalmid. In fact, the carapace of Eysyslopterus and other basal genera belonging to superfamilies, Orcanopterus and Herefordopterus, were almost identical. In the waeringopteroid Orcanopterus, the eyes were separated from the margin by the marginal rim, whereas in Herefordopterus they were completely marginal, a feature present in all pterygotioid genera.[4] In addition, the triangular anterior carapace margin present in Eysyslopterus was shared with Hughmilleria, indicating that it might be a plesiomorphic trait (a trait present in a common ancestor).[7] These characteristics have led some authors to question whether Eysyslopterus really represents an adelophthalmid or the sister taxon of a group formed by Pterygotioidea and Adelophthalmoidea, but until more fossil material is found this can not be proven.[4]

The cladogram below presents the inferred phylogenetic positions of most of the genera included in the three most derived superfamilies of the Diploperculata infraorder of eurypterids (Adelophthalmoidea, Pterygotioidea and the waeringopteroids), as inferred by Tetlie and Poschmann in 2008, based on the results of a 2008 analysis specifically pertaining to the Adelophthalmoidea and a preceding 2004 analysis.[4]

| Diploperculata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

The single known specimen of Eysyslopterus has been recovered from Silurian deposits of the Ludlow epoch of the Rootsikula Formation of Saaremaa, Estonia.[4] This formation was the habitat of a fauna of eurypterids, among them Erettopterus laticauda, E. osiliensis, Eurypterus tetragonophthalmus, Mixopterus simonsi and Strobilopterus laticeps. Fossil remains of indeterminate osteostracid and thelodontid fishes have also been found. The habitat in which Eysyslopterus lived is considered to be a nearshore lagoonal quiet community. The lithology (the physical characteristics of the rocks) of the zone was composed of mudcrack and burrows of dolomite and limestone.[8]

References

- Lamsdell, James C.; Braddy, Simon J. (2009-10-14). "Cope's Rule and Romer's theory: patterns of diversity and gigantism in eurypterids and Palaeozoic vertebrates". Biology Letters: rsbl20090700. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0700. ISSN 1744-9561. PMID 19828493. Supplementary information Archived 2018-02-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Shpinev, Evgeniy S.; Filimonov, A. N. (2018). "A New Record of Adelophthalmus (Eurypterida, Chelicerata) from the Devonian of the South Minusinsk Depression". Paleontological Journal. 52 (13): 1553–1560. doi:10.1134/S0031030118130129.

- Størmer, Leif (1934). A new eurypterid from the Saaremaa- (Oesel-) beds in Estonia. 37. Publications of the Geological Institution of the University of Tartu. pp. 1–8. OCLC 1006783631.

- Erik Tetlie, O; Poschmann, Markus (2008-06-01). "Phylogeny and palaeoecology of the Adelophthalmoidea (Arthropoda; Chelicerata; Eurypterida)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (2): 237–249. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002416.

- Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1961). "The Silurian Eurypterida of the Welsh Borderland". Journal of Paleontology. 35 (4): 789–835. JSTOR 1301214.

- Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2018. A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives. In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern.

- Ciurca, Samuel J.; Tetlie, O. Erik (2007). "Pterygotids (Chelicerata; Eurypterida) from the Silurian Vernon Formation of New York". Journal of Paleontology. 81 (4): 725–736. doi:10.1666/pleo0022-3360(2007)081[0725:PEFTSV]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-3360.

- "Eurypterid-Associated Biota of the Rootsikula Horizon, Saaremaa, Estonia: Rootsikula, Estonia". The Paleobiology Database.