Pixie

A pixie (also pixy, pixi, pizkie, piskie and pigsie as it is sometimes known in Cornwall) is a mythical creature of British folklore. Pixies are considered to be particularly concentrated in the high moorland areas around Devon[1] and Cornwall,[2] suggesting some Celtic origin for the belief and name.

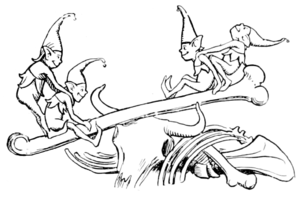

Pixies playing on the skeleton of a cow, drawn by John D. Batten c.1894 | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature Fairy Sprite |

|---|---|

| Country | Devon and Cornwall |

| Region | Devon and Cornwall |

Akin to the Irish and Scottish Aos Sí, pixies are believed to inhabit ancient underground ancestor sites such as stone circles, barrows, dolmens, ringforts or menhirs.[3]

In traditional regional lore, pixies are generally benign, mischievous, short of stature and attractively childlike; they are fond of dancing and gather outdoors in huge numbers to dance or sometimes wrestle, through the night, demonstrating parallels with the Cornish plen-an-gwary and Breton Fest Noz (Cornish: troyl) folk celebrations originating in the medieval period. In modern times they are usually depicted with pointed ears, and often wearing a green outfit and pointed hat although traditional stories describe them wearing dirty ragged bundles of rags which they happily discard for gifts of new clothes.[4] Sometimes their eyes are described as being pointed upwards at the temple ends. These, however, are Victorian era conventions and not part of the older mythology.

Etymology and origin

The origin of the name pixie is uncertain. Some have speculated that it comes from the Swedish dialectal pyske meaning small fairy.[5] Others have disputed this, given there is no plausible case for Nordic dialectal survivals in southwest Britain, claiming instead - in view of the Cornish origin of the piskie - that the term is more probably Celtic in origin, though no clear ancestor of the word is known. The term Pobel Vean ('Little People') is often used to refer to them collectively.[6][7] Very similar analogues exist in closely related Irish (Aos Sí), Manx (Mooinjer veggey) Welsh Tylwyth Teg ('Fair Family'), and Breton (korrigan) culture, although their common names are unrelated, even within areas of language survival there is a very high degree of local variation of names. In west Penwith, the area of late survival of the Cornish language, spriggans are distinguished from pixies by their malevolent nature. Closely associated with tin mining in Cornwall are the subterranean ancestral knockers.

Pixie mythology is believed to pre-date Christian presence in Britain. In the Christian era they were sometimes said to be the souls of children who had died un-baptised. These children would change their appearance to pixies once their clothing was placed in clay funeral pots used in their earthly lives as toys. By 1869 some were suggesting that the name pixie was a racial remnant of Pictic tribes who used to paint and tattoo their skin blue, an attribute often given to pixies. Indeed, the Picts gave their name to a type of Irish Pixie called a Pecht.[8] This suggestion is still met in contemporary writing, but there is no proven connection and the etymological connection is doubtful.[9] Some 19th-century researchers made more general claims about pixie origins, or have connected them with the Puck (Cornish Bucca), a mythological creature sometimes described as a fairy; the name Puck is also of uncertain origin, Irish Púca, Welsh Pwca.

The earliest published version of The Three Little Pigs story is from Dartmoor in 1853 and has three little pixies in place of the pigs.[10] In older Westcountry dialect modern Received Pronunciation letter pairs are sometimes transposed from the older Saxon spelling (waps for wasp, aks for ask and so on) resulting in piskies in place of modern piksies (pixies) as still commonly found in Devon and Cornwall to modern times.

Until the advent of more modern fiction, pixie mythology was localised to Britain. Some have noted similarities to "northern fairies", Germanic and Scandinavian elves,[11] or Tomte but pixies are distinguished from them by the myths and stories of Devon and Cornwall.

Cornwall and Devon

Before the mid-19th century, pixies and fairies were taken seriously in much of Cornwall and Devon. Books devoted to the homely beliefs of the peasantry are filled with incidents of pixie manifestations. Some locales are named for the pixies associated with them. In Devon, near Challacombe, a group of rocks are named after the pixies said to dwell there. At Trevose Head in Cornwall, 600 pixies were said to have gathered dancing and laughing in a circle that had appeared upon the turf until one of their number, named Omfra, lost his laugh. After searching amongst the barrows of the ancient kings of Cornwall on St Breock Downs, he wades through the bottomless Dozmary Pool on Bodmin Moor until his laugh is restored by King Arthur in the form of a Chough.[12] In some areas belief in pixies and fairies as real beings persists.

In the legends associated with Dartmoor, pixies (or piskeys) are said to disguise themselves as a bundle of rags to lure children into their play. The pixies of Dartmoor are fond of music and dancing and for riding on Dartmoor colts. These pixies are generally said to be helpful to normal humans, sometimes helping needy widows and others with housework. They are not completely benign however, as they have a reputation for misleading travellers (being "pixy-led", the remedy for which is to turn your coat inside out).[13][14]

The queen of the Cornish pixies is said to be Joan the Wad (torch), and she is considered to be good luck or bring good luck. In Devon, pixies are said to be "invisibly small, and harmless or friendly to man."

In some of the legends and historical accounts they are presented as having near-human stature. For instance, a member of the Elford family in Tavistock, Devon, successfully hid from Cromwell's troops in a pixie house.[15] Though the entrance has narrowed with time, the pixie house, a natural cavern on Sheep Tor, is still accessible.

At Buckland St. Mary, Somerset, pixies and fairies are said to have battled each other. Here the pixies were victorious and still visit the area, whilst the fairies are said to have left after their loss.[16]

By the early 19th century their contact with humans had diminished. In Samuel Drew’s 1824 book Cornwall[17] one finds the observation: "The age of pixies, like that of chivalry, is gone. There is, perhaps, at present hardly a house they are reputed to visit. Even the fields and lanes which they formerly frequented seem to be nearly forsaken. Their music is rarely heard."

Pixie Day

Pixie Day is an old tradition which takes place annually in the East Devon town of Ottery St. Mary in June. The day commemorates a legend of pixies being banished from the town to local caves known as the "Pixie's Parlour".

The Pixie Day legend originates from the early days of Christianity, when a local bishop decided to build a church in Otteri (Ottery St. Mary), and commissioned a set of bells to come from Wales, and to be escorted by monks on their journey.

On hearing of this, the pixies were worried, as they knew that once the bells were installed it would be the death knell of their rule over the land. So they cast a spell over the monks to redirect them from the road to Otteri to the road leading them to the cliff's edge at Sidmouth. Just as the monks were about to fall over the cliff, one of the monks stubbed his toe on a rock and said "God bless my soul" and the spell was broken.

The bells were then brought to Otteri and installed. However, the pixies' spell was not completely broken; each year on a day in June the "pixies" come out and capture the town's bell ringers and imprison them in Pixies' Parlour to be rescued by the Vicar of Ottery St. Mary. This legend is re-enacted each year by the Cub and Brownie groups of Ottery St. Mary, with a specially constructed Pixies' Parlour in the Town Square (the original Pixie's Parlour can be found along the banks of the River Otter).

Characteristics

Pixies are variously described in folklore and fiction.

They are often described as ill-clothed or naked.[18] In 1890, William Crossing noted a pixie's preference for bits of finery: "Indeed, a sort of weakness for finery exists among them, and a piece of ribbon appears to be... highly prized by them."[19]

Some pixies are said to steal children or to lead travellers astray. This seems to be a cross-over from fairy mythology and not originally attached to pixies; in 1850, Thomas Keightley observed that much of Devon pixie mythology may have originated from fairy myth.[20] Pixies are said to reward consideration and punish neglect on the part of larger humans, for which Keightley gives examples. By their presence they bring blessings to those who are fond of them.

Pixies are drawn to horses, riding them for pleasure and making tangled ringlets in the manes of those horses they ride. They are "great explorers familiar with the caves of the ocean, the hidden sources of the streams and the recesses of the land."[21]

Some find pixies to have a human origin or to "partake of human nature", in distinction to fairies whose mythology is traced to immaterial and malignant spirit forces. In some discussions pixies are presented as wingless, pygmy-like creatures, however this is probably a later accretion to the mythology.

One British scholar stated his belief that "Pixies were evidently a smaller race, and, from the greater obscurity of the ... tales about them, I believe them to have been an earlier race."[22]

Literary interpretations

Many Victorian-era poets saw them as magical beings. An example is Samuel Minturn Peck; in his poem The Pixies he writes:[23]

- ‘Tis said their forms are tiny, yet

- All human ills they can subdue,

- Or with a wand or amulet

- Can win a maiden’s heart for you;

- And many a blessing know to stew

- To make to wedlock bright;

- Give honour to the dainty crew,

- The Pixies are abroad tonight.

The late 19th-century English poet Nora Chesson summarised pixie mythology fairly well in a poem entitled The Pixies.[24] She gathered all the speculations and myths into verse:

|

Have e’er you seen the Pixies, the fold not blest or banned? They walk upon the waters; they sail upon the land, They make the green grass greener where’er their footsteps fall, The wildest hind in the forest comes at their call. They steal from bolted linneys, they milk the key at grass, The maids are kissed a-milking, and no one hears them pass. They flit from byre to stable and ride unbroken foals, They seek out human lovers to win them souls. |

The Pixies know no sorrow, the Pixies feel no fear, They take no care for harvest or seedtime of the year; Age lays no finger on them, the reaper time goes by The Pixies, they who change not, nor grow old or die. The Pixies though they love us, behold us pass away, And are not sad for flowers they gathered yesterday, To-day has crimson foxglove. If purple hose-in-hose withered last night To-morrow will have its rose. |

|---|

She touches on all the essentials, including even more modern accretions. Pixies are "in-between", not cursed by God or especially blessed. They do the unexpected, they bless the land, and are forest creatures whom other wild creatures find alluring and non-threatening. They love humans, taking some for mates, and are nearly ageless. They are winged, flitting from place to place.

The Pixie Day tradition in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s hometown of Ottery St Mary in East Devon was the inspiration for his poem Song of the Pixies.[25]

The Victorian-era writer Mary Elizabeth Whitcombe divided pixies into tribes according to personality and deeds.[26] The novelist Anna Eliza Bray suggested that pixies and fairies were distinct species.[27]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pixies (fantasy creatures). |

- Colt pixie

- Nisse/Tomte

- Goblin

- Jinn

- Leprechaun

- Peter and the Piskies: Cornish Folk and Fairy Tales

- Sylph

- Pixie (comics)

- Tinker Bell

- Puck

References

- R. Totnea: "Pixies", Once a Week, 25 May 1867, page 608, notes the prevalence of belief in Pixies in Devon.

- "The Folk-Lore of Devon", Fraser's Magazine, December 1875, page 773ff.

- Imagined Landscapes:Archaeology, Perception and Folklore in the Study of Medieval Devon, Lucy Franklin , 2006

- English forests and forest trees, historical, legendary, and descriptive, Ingram, Cooke, and co., 1853

- E. M. Kirkpatrick, ed. (1983). Chambers 20th Century Dictionary (New ed.). p. 978.

- Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Traditional Cornish Stories and Rhymes, 1992 edition, Lodenek Press

- Irish Fairies by Bob Curran, Apletree 2007 ISBN 1847580009

- "South Coast Sunterings in England", in: Harpers New Monthly Magazine, (1869) pp. 29–41.

- English Forests and Forest Trees: Historical, Legendary, and Descriptive (London: Ingram, Cooke, and Company, 1853), pp. 189-90

- e.g. John Thackray Bunce: Fairy Tales: Their Origin and Meaning 1878, page 133.

- traditional Cornish Stories and Rhymes, 1992 edition, Lodenek Press

- William Crossing, Tales of the Dartmoor Pixies, 1890, page 6.

- Simon Young (2016). "Pixy-led in Devon and the South West". Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association. 148: 311–336.

- A Handbook for Travellers in Devon, 1887 edition, page 230.

- Katherine Mary Briggs: The Fairies in Tradition and Literature, page 179.

- The History of Cornwall From the Earliest Records & Traditions, to the Present Time, 2 vols. 1824.

- Robert Hunt: Popular Romances of the West of England, 1881, page 96.

- William Crossing: Tales of the Dartmoor Pixies, 1890, page 5.

- The Fairy Mythology, 1850, page 299.

- Devon Pixies, Once A Week, 23 February 1867, pages 204–5.

- C. Spence Bate: "Grimspound and Its Associated Relics", Annual Report of the Transactions of the Plymouth Institution, Vol. 5. part 1, 1873–4, page 46.

- Ballads and Rondeaus, 1881, page 47.

- Nora Chesson: Aquamarines, London, 1902, page 81.

- Shed (editor): Complete Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Vol. 7, 1854, page 24.

- Bygone Days of Devon and Cornwall, 1874, page 45.

- Legends, Superstitions and Sketches of Devonshire, 1844, page 169.