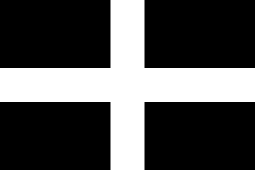

Cormoran

Cormoran (/ˈkɔːrməræn/ or /ˈkɔːrmərən/) is a giant associated with St. Michael's Mount in the folklore of Cornwall. Local tradition credits him with creating the island, in some versions with the aid of his wife Cormelian, and using it as a base to raid cattle from the mainland communities. Cormoran appears in the English fairy tale "Jack the Giant Killer" as the first giant slain by the hero, Jack, and in tales of "Tom the Tinkeard" as a giant too old to present a serious threat.

Origin

One of many giants featured in Cornish folklore, the character derives from local traditions about St. Michael's Mount. The name "Cormoran" is not found in the early traditions; it first appears in the chapbook versions of the "Jack the Giant Killer" story printed in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Nottingham, and is not of Cornish origin.[2] The name may be related to Corineus, the legendary namesake of Cornwall. Corineus is associated with St. Michael's Mount, and is credited with defeating a giant named Gogmagog in Geoffrey of Monmouth's influential pseudohistory Historia Regum Britanniae, which may be a prototype of the Cormoran tradition.[3]

Appearances

Local traditions

The giant eventually known as Cormoran is attributed with constructing St. Michael's Mount, a tidal island off Cornwall's southern coast. According to the folklore, he carried white granite from the mainland at low tide to build the island. In some versions, the giant's wife, Cormelian, assisted by carrying stones in her apron. According to one version, when Cormoran fell asleep from exhaustion, his more industrious wife fetched greenstone from a nearer source, eschewing the less accessible granite. When she was halfway back, Cormoran awoke to discover Cormelian bringing different stones than he wanted, and kicked her. The stones fell from her apron and formed Chapel Rock.[3][4]

From his post at St. Michael's Mount, Cormoran raided the countryside for cattle.[5] He was distinguished by having six digits on each hand and foot.[6] Folklorist Mary Williams reported being told that the skeleton of a man over seven feet tall had been found during an excavation at the Mount.[7]

Cormoran is often associated with the giant of Trencrom in local folklore. The two are said to have thrown boulders back and forth as recreation; this is given as the explanation for the many loose boulders found throughout the area. In one version, the Trencrom giant threw an enormous hammer over for Cormoran, but accidentally hit and killed Cormelian; they buried her at Chapel Rock.[5]

Jack the Giant Killer

The giant of St. Michael's Mount also appears in the English fairy tale "Jack the Giant Killer", early chapbook versions of which are the first to name him Cormoran.[2] According to Joseph Jacobs' account, Cormoran is 5.5 m (18 ft) tall and measures about 2.75 m (9 ft) around the waist.[8][9] He lives in a cave on St Michael's Mount, using the times of ebb tide to walk to the mainland.[8] He regularly raids the countryside, "feast[ing] on poor souls…gentleman, lady, or child, or what on his hand he could lay,"[9] and "making nothing of carrying half-a-dozen oxen on his back at a time; and as for…sheep and hogs, he would tie them around his waist like a bunch of tallow-dips."[8]

In Jacobs's version, the councillors of Penzance convene during the winter to solve the issue of Cormoran's raids on the mainland. After offering the giant's treasure as reward for his disposal, a villein farmer's boy named Jack takes it upon himself to kill Cormoran.[8] Older chapbooks make no reference to the council, and attribute Jack's actions to a love for fantasy, chivalry, and adventure.[10] In both versions, in the late evening Jack swims to the island and digs a 6.75 m (22 ft) trapping pit,[8][10] although some local legends place the pit to the north in Morvah.[11]

After completing the pit the following morning, Jack blows a horn to awaken the giant. Cormoran storms out, threatening to broil Jack whole. But falls into the hidden pit and after being taunted for some time, Cormoran is killed by a blow from a pickaxe or mattock.[9] After filling in the hole, Jack retrieves the giant's treasure. According to the Morvah tradition, a rock is placed over the grave. Today this rock is called Giant's Grave. Local lore holds that the giant's ghost can sometimes be heard beneath it.

For his service to Penwith, Jack is officially titled "Jack the Giant-Killer" and awarded a belt on which was written:[7][8][12]

Here's the right valiant Cornishman,

Who slew the giant Cormoran.

Tom the Tinkeard

The giant of St. Michael's Mount also appears in the drolls about Tom the Tinkeard, a local Cornish variant of "Tom Hickathrift". William Bottrell recorded a tale of the giant's last raid: here, the giant is not killed, but lives to grow old and frail. Becoming hungry, he makes one last incursion to steal a bullock from an enchanter on the mainland. However, the enchanter strikes him immobile as the sea rises around him. He must spend the evening in the cold sea with the bull hanging from around his neck; he subsequently retreats to the Mount hungry and defeated. Later, Tom visits the giant and takes pity on him, and arranges for his aunt Nancy of Gulval to sell him her store of eggs and butter. This both feeds the giant and makes Nancy's family rich.[13]

References

- "Chapbooks". L390 Children's Literature. Archived from the original on 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- Spooner, B. C. (1965). "The Giants of Cornwall". Folklore. 76 (1): 22. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1965.9716983. JSTOR 1258088.

- Rose, Carol (2001). Giants, Monsters, and Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 87. ISBN 0393322114. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- Spooner, B. C. (1965). "The Giants of Cornwall". Folklore. 76 (1): 18. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1965.9716983. JSTOR 1258088.

- Spooner, B. C. (1965). "The Giants of Cornwall". Folklore. 76 (1): 17. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1965.9716983. JSTOR 1258088.

- Spooner, B. C. (1965). "The Giants of Cornwall". Folklore. 76 (1): 19. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1965.9716983. JSTOR 1258088.

- Williams, Mary (1963). "Folklore and Placenames". Folklore. 76 (1): 366. JSTOR 1258967.

- Jacobs, Joseph (1890). "Jack the Giant-Killer". English Fairy Tales. London: David Nutt.

- "Jack the Giant Killer, a Hero celebrated by ancient Historians". Banbury. c. 1820. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- "Jack the Giant-Killer: Page 1". Archived from the original on 2010-07-08. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- "St. Michael's Mount and the giant Cormoran". Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- Spooner, B. C. (1965). "The Giants of Cornwall". Folklore. 76 (1): 26. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1965.9716983. JSTOR 1258088.

- Spooner, B. C. (1965). "The Giants of Cornwall". Folklore. 76 (1): 27. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1965.9716983. JSTOR 1258088.