Kodama (spirit)

Kodama (木霊, 木魂 or 木魅) are spirits in Japanese folklore that inhabit trees, similar to the dryads of Greek mythology. The term is also used to denote a tree in which a kodama supposedly resides. The phenomenon known as yamabiko, when sounds make a delayed echoing effect in mountains and valleys, is sometimes attributed to this kind of spirit and may also be referred to as "kodama".

Summary

These spirits are considered to nimbly bustle about mountains at will. A kodama's outer appearance is very much like an ordinary tree, but if one attempts to cut it down, one would become cursed etc., and it is thus considered to have some kind of mysterious supernatural power. The knowledge of those trees that have kodama living in them is passed down by the elderly of that area over successive generations and they are protected, and it is also said that trees that have a kodama living in them are of certain species. There is also a theory that when old trees are cut, blood could come forth from them.[1]

Kodama is also seen as something that can be understood as mountain gods, and a tree god from the 712 CE Kojiki, Kukunochi no Kami, has been interpreted as a kodama, and in the Heian period dictionary, the Wamyō Ruijushō, there is a statement on tree gods under the Japanese name "Kodama" (古多万). In The Tale of Genji, there are statements such as "is it an oni, a god (kami), a fox (kitsune), or a tree spirit (kodama)" and "the oni of a kodama," and thus, it can be seen that kodama are seen to be close to yōkai.[2] They are said to take on the appearance of atmospheric ghost lights, of beasts, and of humans, and there is also a story where a kodama who, in order to meet a human it fell in love with, took on the appearance of a human itself.[3]

In Aogashima in the Izu Islands, shrines are created at the base of large Cryptomeria trees (sugi) in the mountains and are worshipped to under the name "kidama-sama" and "kodama-sama" and thus the vestiges of belief in tree spirits can be seen.[2] Also, in the village of Mitsune on Hachijō-jima, whenever a tree is cut, there was a tradition that one must offer a festival to the tree's spirit "kidama-sama."[4]

On Okinawa Island, tree spirits are called "kiinushii" and whenever a tree is cut down, one would first pray to kiinushii and then cut it. Also, when there is an echoing noise of what sounds like a fallen tree at the dead of night, even though there are no actual fallen trees, it is said to be the anguishing voice of kiinushii and it is said that in times like these, the tree would then wither several days later. The kijimuna, which is known as a yōkai on Okinawa, is also sometimes said to be a type of kiinushii or a personification of a kiinushii.[2][5]

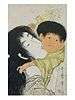

In the collection of yōkai depictions, the Gazu Hyakki Yagyō by Toriyama Sekien, under the title 木魅 ("kodama"), an aged man and woman are depicted standing alongside the trees and here it is stated that when a tree has passed a hundred years of age, a divine spirit would come dwell inside it and show its appearance.[6] According to the 13th century Ryōbu Shinto manual Reikiki, kodama can be found in groups in the inner reaches of mountains. They occasionally speak and can especially be heard when a person dies.[7]

In modern times, cutting down a tree which houses a kodama is thought to bring misfortune and such trees are often marked with shimenawa rope.[8]

See also

- Anito

- Balete tree

- Tree spirits

References

- 草野巧 (1997). 幻想動物事典. 新紀元社. p. 138. ISBN 978-4-88317-283-2.

- 今野円輔編著 (1981). 日本怪談集 妖怪篇. 現代教養文庫. 社会思想社. pp. 290–303. ISBN 978-4-390-11055-6.

- 多田克己 (1990). 幻想世界の住人たち. Truth In Fantasy. IV. 新紀元社. p. 335. ISBN 978-4-915146-44-2.

- 萩原龍夫 (1977) [1955]. 民俗学研究所編 (ed.). 綜合日本民俗語彙. 第1巻. 柳田國男監修 (改訂版 ed.). 平凡社. p. 457. ISBN 978-4-582-11400-3.

- 村上健司編著 (2005). 日本妖怪大事典. Kwai books. 角川書店. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-4-04-883926-6.

- 稲田篤信・田中直日編 (1992). 鳥山石燕 画図百鬼夜行. 高田衛監修. 国書刊行会. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-4-336-03386-4.

- 叶精二 "「もののけ姫」を読み解く Archived 2012-07-24 at the Wayback Machine" Tokyo: Comic Box, 1997

- Mizuki, Shigeru (2003). Mujara 1: Kantō, Hokkaidō, Okinawa-hen (in Japanese). Japan: Soft Garage. p. 51. ISBN 978-4-86133-004-9.

External links

- Kodama – The Tree Spirit at hyakumonogatari.com (English).