Melusine

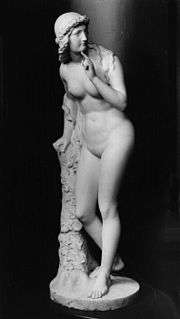

Melusine (French: [melyzin]) or Melusina is a figure of European folklore and mythology, a female spirit of fresh water in a sacred spring or river. She is usually depicted as a woman who is a serpent or fish from the waist down (much like a mermaid). She is also sometimes illustrated with wings, two tails, or both. Her legends are especially connected with the northern and western areas of France, Luxembourg, and the Low Countries. The House of Luxembourg (which ruled the Holy Roman Empire from AD 1308 to AD 1437 as well as Bohemia and Hungary), the House of Anjou and their descendants the House of Plantagenet (kings of England) and the French House of Lusignan (kings of Cyprus from AD 1205–1472, and for shorter periods over Armenia and Jerusalem) are said in folk tales and medieval literature to be descended from Melusine.

One tale says Melusine herself was the daughter of the fairy Pressyne and king Elinas of Albany (now known as Scotland). Melusine's mother leaves her husband, taking her daughters to the isle of Avalon after he breaks an oath never to look in at her and her daughter in their bath. The same pattern appears in stories where Melusine marries a nobleman only after he makes an oath to give her privacy in her bath; each time, she leaves the nobleman after he breaks that oath. Shapeshifting and flight on wings away from oath-breaking husbands also figure in stories about Melusine. According to Sabine Baring-Gould in Curious Tales of the Middle Ages, the pattern of the tale is similar to the Knight of the Swan legend which inspired the character "Lohengrin" in Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival.[1]

Literary versions

The most famous literary version of Melusine tales, that of Jean d'Arras, compiled about 1382–1394, was worked into a collection of "spinning yarns" as told by ladies at their spinning coudrette (coulrette (in French)). He wrote The Romans of Partenay or of Lusignen: Otherwise known as the Tale of Melusine, giving source and historical notes, dates and background of the story. He goes into detail and depth about the relationship of Melusine and Raymondin, their initial meeting and the complete story.

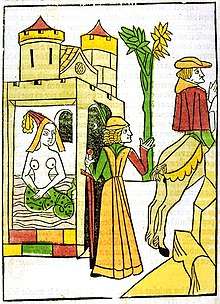

The tale was translated into German in 1456 by Thüring von Ringoltingen, which version became popular as a chapbook. It was later translated into English, twice, around 1500, and often printed in both the 15th century and the 16th century. There is also a Castilian and a Dutch translation, both of which were printed at the end of the 15th century.[2] A prose version is entitled the Chronique de la princesse (Chronicle of the Princess).

It tells how in the time of the Crusades, Elynas, the King of Albany (an old name for Scotland or Alba), went hunting one day and came across a beautiful lady in the forest. She was Pressyne, mother of Melusine. He persuaded her to marry him but she agreed, only on the promise—for there is often a hard and fatal condition attached to any pairing of fay and mortal—that he must not enter her chamber when she birthed or bathed her children. She gave birth to triplets. When he violated this taboo, Pressyne left the kingdom, together with her three daughters, and traveled to the lost Isle of Avalon.

The three girls—Melusine, Melior, and Palatyne—grew up in Avalon. On their fifteenth birthday, Melusine, the eldest, asked why they had been taken to Avalon. Upon hearing of their father's broken promise, Melusine sought revenge. She and her sisters captured Elynas and locked him, with his riches, in a mountain. Pressyne became enraged when she learned what the girls had done, and punished them for their disrespect to their father. Melusine was condemned to take the form of a serpent from the waist down every Saturday. In other stories, she takes on the form of a mermaid.

Raymond of Poitou came across Melusine in a forest of Coulombiers in Poitou in France, and proposed marriage. Just as her mother had done, she laid a condition: that he must never enter her chamber on a Saturday. He broke the promise and saw her in the form of a part-woman, part-serpent, but she forgave him. When, during a disagreement, he called her a "serpent" in front of his court, she assumed the form of a dragon, provided him with two magic rings, and flew off, never to return.[3]

In The Wandering Unicorn by Manuel Mujica Láinez, Melusine tells her tale of several centuries of existence, from her original curse to the time of the Crusades.[4]

Legends

Melusine legends are especially connected with the northern areas of France, Poitou and the Low Countries, as well as Cyprus, where the French Lusignan royal house that ruled the island from 1192 to 1489 claimed to be descended from Melusine. Oblique reference to this was made by Sir Walter Scott who told a Melusine tale in Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802–1803) stating that

the reader will find the fairy of Normandy, or Bretagne, adorned with all the splendour of Eastern description. The fairy Melusina, also, who married Guy de Lusignan, Count of Poitou, under condition that he should never attempt to intrude upon her privacy, was of this latter class. She bore the count many children, and erected for him a magnificent castle by her magical art. Their harmony was uninterrupted until the prying husband broke the conditions of their union, by concealing himself to behold his wife make use of her enchanted bath. Hardly had Melusina discovered the indiscreet intruder, than, transforming herself into a dragon, she departed with a loud yell of lamentation, and was never again visible to mortal eyes; although, even in the days of Brantome, she was supposed to be the protectress of her descendants, and was heard wailing as she sailed upon the blast round the turrets of the castle of Lusignan the night before it was demolished.

The Luxembourg family also claimed descent from Melusine through their ancestor Siegfried.[5] When in 963 A.D. Count Siegfried of the Ardennes (Sigefroi in French; Sigfrid in Luxembourgish) bought the feudal rights to the territory on which he founded his capital city of Luxembourg, his name became connected with the local version of Melusine. This Melusina had essentially the same magic gifts as the ancestress of the Lusignans, magically making the Castle of Luxembourg on the Bock rock (the historical center point of Luxembourg City) appear the morning after their wedding. On her terms of marriage, she too required one day of absolute privacy each week. Alas, Sigfrid, as the Luxem-bourgish call him, "could not resist temptation, and on one of the forbidden days he spied on her in her bath and discovered her to be a mermaid. When he let out a surprised cry, Melusina caught sight of him, and her bath immediately sank into the solid rock, carrying her with it. Melusina surfaces briefly every seven years as a beautiful woman or as a serpent, holding a small golden key in her mouth. Whoever takes the key from her will set her free and may claim her as his bride." In 1997 Luxembourg issued a postage stamp commemorating her.[6]

Martin Luther knew and believed in the story of another version of Melusine, die Melusina zu Lucelberg (Lucelberg in Silesia), whom he referred to several times as a succubus (Works, Erlangen edition, volume 60, pp 37–42). Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote the tale of Die Neue Melusine in 1807 and published it as part of Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre. The playwright Franz Grillparzer brought Goethe's tale to the stage and Felix Mendelssohn provided a concert overture "The Fair Melusina," his Opus 32.

Melusine is one of the pre-Christian water-faeries who were sometimes responsible for changelings. The "Lady of the Lake", who spirited away the infant Lancelot and raised the child, was such a water nymph. Other European water sprites include Lorelei and the nixie.

"Melusina" would seem to be an uneasy name for a girl-child in these areas of Europe, but Ehrengard Melusine von der Schulenburg, Duchess of Kendal and Munster, mistress of George I of Great Britain, was christened Melusine in 1667.

The chronicler Gerald of Wales reported that Richard I of England was fond of telling a tale according to which he was a descendant of a countess of Anjou who was in fact the fairy Melusine.[7] The Angevin legend told of an early Count of Anjou who met a beautiful woman when in a far land, where he married her. He had not troubled to find out about her origins. However, after bearing him four sons, the behaviour of his wife began to trouble the count. She attended church infrequently, and always left before the Mass proper. One day he had four of his men forcibly restrain his wife as she rose to leave the church. Melusine evaded the men and clasped the two youngest of her sons and in full view of the congregation carried them up into the air and out of the church through its highest window. Melusine and her two sons were never seen again. One of the remaining sons was the ancestor, it was claimed, of the later Counts of Anjou and the Kings of England.[8]

Related legends

The Travels of Sir John Mandeville recounts a legend about Hippocrates' daughter. She was transformed into a hundred-foot long dragon by the goddess Diane, and is the "lady of the manor" of an old castle. She emerges three times a year, and will be turned back into a woman if a knight kisses her, making the knight into her consort and ruler of the islands. Various knights try, but flee when they see the hideous dragon; they die soon thereafter. This appears to be an early version of the legend of Melusine.[9]

Structural interpretation

Jacques Le Goff considered that Melusina represented a fertility figure: "she brings prosperity in a rural area...Melusina is the fairy of medieval economic growth".[10]

References in the arts

- Melusine is the subject of Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's novella Undine (1811), Halévy's grand opera La magicienne (1858) and Jean Giraudoux's play Ondine (1939).

- Antonín Dvořák's Rusalka, Opera in three acts, Libretto by Jaroslav Kvapil, is also based on the fairy tale Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué.

- Felix Mendelssohn depicted the character in his concert overture The Fair Melusine (Zum Märchen von der Schönen Melusine), opus 32.

- Marcel Proust's main character compares Gilberte to Melusine in Within a Budding Grove. She is also compared on several occasions to the Duchesse de Guermantes who was (according to the Duc de Guermantes) directly descended from the Lusignan dynasty. In the Guermantes Way, for example, the narrator observes that the Lusignan family "was fated to become extinct on the day when the fairy Melusine should disappear" (Volume II, Page 5, Vintage Edition.).

- The story of Melusine (also called Melusina) was retold by Letitia Landon in the poem "The Fairy of the Fountains" in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1834,[11] and reprinted in her collection The Zenana. Here she is representative of the female poet. An analysis can be found in Anne DeLong, pages 124–131.[12]

- Mélusine appears as a minor character in James Branch Cabell's Domnei: A Comedy of Woman-Worship (1913 as The Soul of Melicent, rev. 1920) and The High Place (1923).

- In Our Lady of the Flowers, Jean Genet twice says that Divine, the main character, is descended from "the siren Melusina" (pp. 198, 298 of the Grove Press English edition (1994)). (The conceit may have been inspired by Genet's reading of Proust.)

- Melusine appears to have inspired aspects of the character Mélisande, who is associated with springs and waters, in Maurice Maeterlinck's play Pelléas and Mélisande, first produced in 1893. Claude Debussy adapted it as an opera by the same name, produced in 1902.

- In Wilhelm Meister's Journeyman Years, Goethe re-tells the Melusine tale in a short story titled "The New Melusine".

- Georg Trakl wrote a poem titled "Melusine".

- Margaret Irwin's fantasy novel These Mortals (1925) revolves around Melusine leaving her father's palace, and having adventures in the world of humans.[13]

- Charlotte Haldane wrote a study of Melusine in 1936 (which her then husband J.B.S. Haldane referred to in his children's book "My Friend Mr Leakey").

- Aribert Reimann composed an opera Melusine, which premiered in 1971.

- The Melusine legend is featured in A. S. Byatt's late 20th century novel Possession. One of the main characters, Christabel LaMotte, writes an epic poem about Melusina.

- Philip the Good's 1454 Feast of the Pheasant featured as one of the lavish 'entremets' (or table decorations) a mechanical depiction of Melusine as a dragon flying around the castle of Lusignan.[14]

- Rosemary Hawley Jarman used a reference from Sabine Baring-Gould's Curious Myths of the Middle Ages[15] that the House of Luxembourg claimed descent from Melusine in her 1972 novel The King's Grey Mare, making Elizabeth Woodville's family claim descent from the water-spirit.[16] This element is repeated in Philippa Gregory's novels The White Queen (2009) and The Lady of the Rivers (2011), but with Jacquetta of Luxembourg telling Elizabeth that their descent from Melusine comes through the Dukes of Burgundy.[17][5]

- In his 2016 novel In Search of Sixpence the writer Michael Paraskos retells the story of Melusine by imagining her as a Turkish Cypriot girl forceably abducted from the island by a visiting Frenchman.

- Kurt Heasley of the US band Lilys wrote a song titled "Melusina" for the 2003 album Precollection.

- French singer Nolwenn Leroy recorded a song titled "Mélusine" on her album Histoires Naturelles in 2005.

- The gothic metal band Leaves' Eyes released a song and EP titled "Melusine" in April 2011.

- In Final Fantasy V, a video game RPG originally released by Squaresoft for the Super Famicom in 1992, Melusine appears as a boss. Her name was mistranslated as "Mellusion" in the PS1 port included as part of Final Fantasy Anthology but was correctly translated in subsequent localizations.

- The fairy is said to be "a recurring metaphor" in Breton's Arcanum 17.

- In Czech and Slovak, the word meluzína refers to wailing wind, usually in the chimney. This is a reference to the wailing Melusine looking for her children.[18]

- In the video game The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, a particularly powerful siren is named Melusine.

- In the video game Final Fantasy XV, the sidequest "O Partner, My Partner" has the player pitted against a level 99 daemon named Melusine, she is depicted as a beautiful woman, wrapped in snakes. In this version she is weak to fire despite usually depicted as a being of water.

- In the movie Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald actress Olwen Fouéré plays a character named "Melusine".

- In the book “Light and Shadow”, part 5 of The Longsword Chronicles by GJ Kelly, 'The Melusine' is the name of a coastal brigantine of the Royal Callodon Navy.

- The video game Sigi - A Fart for Melusina is a parody of the legend. The player character is Siegfried, who tries to rescue his beloved Melusine.

- In June 2019, it was announced that Luxembourg's first petascale supercomputer, a part of the European High-Performance Computing Joint Undertaking (EuroHPC JU) programme, is to be named "Meluxina".[19]

- The Starbucks logo is thought to be Melusine.

See also

- Echidna _(mythology) Greek Mythological serpent woman, mother of monsters

- Legend of the White Snake

- Morgen (mythological creature)

- Neck (water spirit)

- Naiad

- Potamides (mythology)

- Partonopeus de Blois

- Yuki-onna

- Knight of the Swan

References

- Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox, Melusine of Lusignan: foundling fiction in late medieval France. Essays on the Roman de Mélusine (1393) of Jean d'Arras.

- Lydia Zeldenrust, The Mélusine Romance in Medieval Europe: Translation, Circulation, and Material Contexts. (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2020) (on the many translations of the romance, covering French, German, Dutch, Castilian, and English versions) ISBN 9781843845218

- Jean d'Arras, Mélusine, roman du XIVe siècle, ed. Louis Stouff. Dijon: Bernigaud & Privat, 1932. (Scholarly edition of the important medieval French version of the legend by Jean d'Arras.)

- Otto j. Eckert, "Luther and the Reformation," lecture, 1955. e-text

- Proust, Marcel. (C. K. Scott Moncrieff, trans.) Within A Budding Grove. (Page 190)

- Baring-Gould, Sabine (1882). Curious Myths of the Middle Ages. Boston: Roberts Brothers. pp. 343–393.

- Lydia Zeldenrust, The Mélusine Romance in Medieval Europe: Translation, Circulation, and Material Contexts (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2020)

- Boria Sax, The Serpent and the Swan: Animal Brides in Literature and Folklore. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press/ McDonald & Woodward, 1998.

- Láinez, Manuel Mujica (1983) The Wandering Unicorn Chatto & Windus, London ISBN 0-7011-2686-8;

- Philippa Gregory; David Baldwin; Michael Jones (2011). The Women of the Cousins' War. London: Simon & Schuster.

- Luxembourg Stamps: 1997

- Flori, Jean (1999), Richard Coeur de Lion: le roi-chevalier, Paris: Biographie Payot, ISBN 978-2-228-89272-8 (in French)

- Huscroft, R. (2016) Tales From the Long Twelfth Century: The Rise and Fall of the Angevin Empire, Yale University Press, pp. xix–xx

- Christiane Deluz, Le livre de Jehan de Mandeville, Leuven 1998, p. 215, as reported by Anthony Bale, trans., The Book of Marvels and Travels, Oxford 2012, ISBN 0199600600, p. 15 and footnote

- J. Le Goff, Time, Work and Culture in the Middle Ages (London 1982) p. 218-9

- Letitia Landon

- DeLong

- Brian Stableford, " Re-Enchantment in the Aftermath of War", in Stableford, Gothic Grotesques: Essays on Fantastic Literature. Wildside Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4344-0339-1 (p.110-121)

- Jeffrey Chipps Smith, The Artistic Patronage of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (1419–1467), PhD thesis (Columbia University, 1979), p. 146

- "Stephan, a Dominican, of the house of Lusignan, developed the work of Jean d'Arras, and made the story so famous, that the families of Luxembourg, Rohan, and Sassenage altered their pedigrees so as to be able to claim descent from the illustrious Melusina", citing Jean-Baptiste Bullet's Dissertation sur la mythologie française (1771).

- Jarman, Rosemary Hawley (1972). "Foreword". The King's Grey Mare.

- Gregory, Philippa (2009). "Chapter One" (PDF). The White Queen.

- Smith, G.S.; C. M. MacRobert; G. C. Stone (1996). Oxford Slavonic Papers, New Series. XXVIII (28, illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-19-815916-2.

- "Le superordinateur luxembourgeois "Meluxina" fera partie du réseau européen EuroHPC" [Luxembourgish supercomputer "Meluxina" will be part of the EuroHPC European network]. gouvernement.lu (in French). 14 June 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Letitia Elizabeth Landon. Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1834.

- Anne DeLong. Mesmerism, Medusa and the Muse, The Romantic Discourse of Spontaneous Creativity, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Melusine. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- "Melusina", translated legends about mermaids and water sprites that marry mortal men, with sources noted, edited by D. L. Ashliman, at University of Pittsburgh

- Terri Windling, "Married to Magic: Animal Brides and Bridegrooms in Folklore and Fantasy"

- Sir Walter Scott, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (e-text)

- Jean D'Arras, Melusine, Archive.org

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.