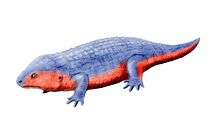

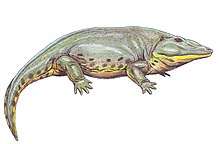

Eryops

Eryops /ˈɛri.ɒps/ meaning "drawn-out face" because most of its skull was in front of its eyes (Greek ἐρύειν, eryein = drawn-out + ὤψ, ops = face) is a genus of extinct, amphibious temnospondyls. It contains the single species Eryops megacephalus, the fossils of which are found mainly in early Permian (about 295 million years ago) rocks of the Texas Red Beds, located in Archer County, Texas. Fossils have also been found in late Carboniferous period rocks from New Mexico. Several complete skeletons of Eryops have been found in lower Permian rocks, but skull bones and teeth are its most common fossils.

| Eryops | |

|---|---|

| Cast of a skeleton and tadpole (formerly known as Pelosaurus), National Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Temnospondyli |

| Family: | †Eryopidae |

| Genus: | †Eryops Cope, 1887 |

| Species: | †E. megacephalus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Eryops megacephalus Cope, 1877 | |

Description

Eryops averaged a little over 1.5–2.0 metres (4.9–6.6 ft) long and could grow up to 3 metres (9.8 ft),[1] making them among the largest land animals of their time. Adults weighed about 90 kilograms (200 lb). The skull was proportionately large, being broad and flat and reaching lengths of 60 centimetres (2.0 ft). It had an enormous mouth with many curved teeth like the frog. Its teeth had enamel with a folded pattern, leading to its early classification as a "labyrinthodont" ("maze toothed"). The shape and cross section of Eryops teeth made them exceptionally strong and resistant to stresses.[2] The palate, or roof of the mouth, contained three pairs of backward-curved fangs, and was covered in backward-pointing bony projections which would have been used to trap slippery prey once caught. This, coupled with the wide gape, suggest an inertial method of feeding, in which the animal would grasp its prey and thrust forward, forcing the prey farther back into its mouth.[2]

Eryops was much more strongly built and sturdy than its relatives, and had the most massive and heavily ossified skeleton of all known temnospondyls.[3] The limbs were especially large and strong. The pectoral girdle was highly developed, with a larger size for increased muscle attachments. Most notably, the shoulder girdle was disconnected from the skull, resulting in improved terrestrial locomotion. The crossopterygian cleithrum was retained as the clavicle, and the interclavicle was well-developed, lying on the underside of the chest. In primitive forms, the two clavicles and the interclavicle could have grown ventrally in such a way as to form a broad chest plate, although such was not the case in Eryops. The upper portion of the girdle had a flat scapular blade, with the glenoid cavity situated below performing as the articulation surface for the humerus, while ventrally there was a large flat coracoid plate turning in toward the midline.[4]

The pelvic girdle also was much larger than the simple plate found in fishes, accommodating more muscles. It extended far dorsally and was joined to the backbone by one or more specialized sacral ribs. The hind legs were somewhat specialized in that they not only supported weight, but also provided propulsion. The dorsal extension of the pelvis was the ilium, while the broad ventral plate was composed of the pubis in front and the ischium behind. The three bones met at a single point in the center of the pelvic triangle, called the acetabulum, providing a surface of articulation for the femur.[4]

The texture of Eryops skin was revealed by a fossilized "mummy" described in 1941. This mummy specimen showed that the body in life was covered in a pattern of oval bumps.[5]

Discovery and species

_at_G%C3%B6teborgs_Naturhistoriska_Museum_2355.jpg)

Eryops is currently thought to contain only one species, E. megacephalus, which means "large-headed Eryops". E. megacephalus fossils have been found only in rocks dated to the early Permian period (Sakmarian age, about 295 million years ago) in the southwestern United States, primarily in the Admiral Formation of the Texas Red Beds.[6] During the mid-20th century, some older fossils were classified as a second species of Eryops, E. avinoffi. This species, known from Carboniferous period fossil found in Pennsylvania, had originally been classified in the genus Glaukerpeton. Beginning in the late 1950s, some scientists concluded that Glaukerpeton was too similar to Eyrops to deserve its own genus. However, later studies supported the original classification of Glaukerpeton, finding that it was more primitive than Eryops and some other early temnospondyls.[7] Supposed Eryops fossils also found in older Pennsylvanian epoch rocks of the Conemaugh Group in West Virginia[8] also turned out to be remains of Glaukerpeton.[7] In 2005, a skull clearly belonging to Eryops was found in upper Pennsylvanian epoch rocks of the El Cobre Canyon Formation in New Mexico, representing the oldest known specimen.[9]

Paleobiology

Eryops were among the most formidable early Permian carnivores and perhaps the only ones capable of competing with the dominant synapsids of the time, though because they were semi-aquatic, if not mostly aquatic, as suggested by long bone microanatomy,[10] they probably did not come into frequent competition with synapsids.[11] Eryops lived in lowland habitats in and around ponds, streams, and rivers, and the arrangement and shape of their teeth suggests that they probably ate mostly large fish and aquatic tetrapods.[1] The torso of Eryops was relatively stiff and the tail stout, which would have made them poor swimmers. While they probably fed on fish, adult Eryops must have spent most of their time on land.[1]

Like other large primitive temnospondyls, Eryops would have grown slowly and gradually from aquatic larvae, but they did not go through a dramatic metamorphosis like many modern amphibians. While adults probably lived in ponds and rivers, or may have ventured onto their banks, juvenile Eryops may have lived in swamps, which may have offered more shelter from predators.[1]

References

- Schoch, Rainer R. (2009). "Evolution of life cycles in early amphibians". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 37 (1): 135–162. Bibcode:2009AREPS..37..135S. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100113.

- Rinehart, L. F.; Lucas, S. G. (2013). "Tooth form and function in temnospondyl amphibians: relationship of shape to applied stress" (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History Bulletin. 61: 533–542.

- Amphibian Evolution: The Life of Early Land Vertebrates

- Pawley, Kat; Warren, Anne (2006). "The appendicular skeleton of Eryops megacephalus Cope, 1877 (Temnospondyli: Eryopoidea) from the Lower Permian of North America". Journal of Paleontology. 80 (3): 561–580. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2006)80[561:TASOEM]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4095151.

- Romer, A. S.; Witter, R. V. (1941). "The skin of the rachitomous amphibian Eryops". American Journal of Science. 239 (11): 822–824. doi:10.2475/ajs.239.11.822.

- Gould, Stephen Jay, ed. The Book Of Life: An Illustrated History of the Evolution of Life on Earth. W.W. Norton: 2001, pg. 94. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- Werneburg, Ralf; Berman, David S (2012). "Revision of the aquatic eryopid temnospondyl Glaukerpeton avinoffi Romer, 1952, from the Upper Pennsylvanian of North America". Annals of Carnegie Museum. 81: 33–60. doi:10.2992/007.081.0103.

- Murphy, James L. (1971). "Eryopsid Remains from the Conemaugh Group, Braxton County, West Virginia". Southeastern Geology. 13 (4): 265–273.

- Werneburg, R.; S.G. Lucas; J.W. Schneider; L.F. Rinehart (2010). "First Pennsylvanian Eryops (Temnospondyli) and its Permian record from New Mexico". In Lucas, S.G.; J.W. Schneider; J.A. Spielmann (eds.). Carboniferous-Permian transition in Canõn del Cobre, northern New Mexico. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 49. pp. 129–135.

- Quémeneur, S.; de Buffrénil, V.; Laurin, M. (2013). "Microanatomy of the amniote femur and inference of lifestyle in limbed vertebrates". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 109 (3): 644–655. doi:10.1111/bij.12066.

- Van Valkenburgh, B.; Jenkins, I. (2002). "Evolutionary patterns in the history of Permo-Triassic and Cenozoic synapsid predators". Paleontological Society Papers. 8: 267–288.