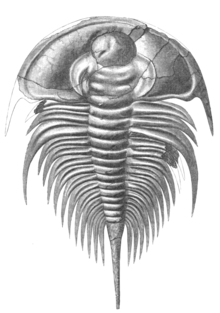

Olenellus

Olenellus is an extinct genus of redlichiid trilobites, with species of average size (about 5 centimetres or 2.0 inches long). It lived during the Botomian and Toyonian stages (Olenellus-zone), 522 to 510 million years ago, in what is currently North-America, part of the paleocontinent Laurentia.[4]

| Olenellus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Olenellus thompsoni | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | Olenellinae |

| Genus: | Olenellus Billings, 1861 |

| Species | |

| |

Etymology

Olenellus means small Olenus, after a genus belonging to the Ptychopariida, to which the type species O. thompsoni was originally assigned. The name Olenus refers to a mythological figure who was turned to stone by the gods. The names of the species have the following derivations.

- agellus comes from the Latin word for field or hamlet.

- chiefensis refers to the Chief Range, which includes the Ruin Wash section, that holds the last of the Olenellina.[3]

- fowleri was named in honor of Ed Fowler, whose quarrying skills exposed the type locality of this species.[3]

- getzi is called after Noah L. Getz, on whose Lancaster estate several Olenellus species were first collected.

- nevadensis refers to the state of Nevada, where this species is found.

- parvofrontatus means ‘small front’ from the Latin words parvus and frontatus, indicating the short distance between the anterior border and the glabella in this species.

- roddyi was named in honor of Dr. H. Justin Roddy (1856-1943), an internationally known naturalist, curator and professor of geology.

- romensis refers to the Rome Formation.

- terminatus is from the Latin terminus, meaning final, indicating the demise of the Olenellus lineage.[3]

Taxonomy

Relationship within the Olenellidae

Olenellus is the only genus currently recognised in the subfamily Olenellinae. The sister group called the Mesonacinae consists of the genera Mesonacis and Mesolenellus.[1]

Status of the clade "Paedeumias"

"Paedeumias" was previously regarded as a genus related to Olenellus[5] or a subgenus being part of Olenellus.[6] Recent analysis shows that there is a group of species formerly assigned to Olenellus (Paedeumias) nested within Olenellus (O. clarki, O. nevadensis, O. parvofrontatus, O. roddyi and O. transitans). However, this group is more closely related to the majority of the remainder of Olenellus species than to O. agellus and O. romensis. This implies that either two new monophyletic subgenera need to be erected, or Olenellus (Paedeumias) and Olenellus (Olenellus) need to be dropped as subgenera, the latter being proposed by Lieberman.[1]

Reassigned species

- O. alabamensis = Fremontella halli

- O. altifrontatus = Bolbolenellus altifrontatus

- O. argentus[5] pl. 40, fig 12, 13, 15, 16, non fig. 14 = Grandinasus argentus

- O. argentus[5] pl. 40, fig 14, non fig. 12, 13, 15, 16 = Holmiella falx

- O. bondoni = Fallotaspis bondoni

- O. bonnensis = Mesonacis bonnensis

- O. brevoculus = Mesonacis bonnensis

- O. broegeri = Callavia broegeri

- O. bristolensis = Bristolia bristolensis

- O. bristolensis[7] p. 8. fig 1-11, non pl. 7, fig 1, 2, 5 = Bristolia harringtoni

- O. bufrontis = Bolbolenellus sphaerulosus

- O. callavei = Callavonia callavei

- O. cylindricus = Mesonacis cylindricus

- O. eagerensis = Mesonacis eagerensis

- O. euryparia = Bolbolenellus euryparia

- O. forresti = Redlichia forresti

- O. fremonti[5] pl. 15, fig. 18 = Bristolia fragilis

- O. fremonti[5] pl. 37, fig. 1, 4-5 = Bolbolenellus euryparia

- O. fremonti[5] pl. 37, fig. 1-2 = Mesonacis fremonti

- O. georgiensis,[8] p. 220, pl. 5, fig. 7, non fig. 6 = Mesonacis vermontanus

- O. gigas = Andalusiana cornuta

- O. gilberti = Bristolia bristolensis

- O. groenlandicus = Bolbolenellus groenlandicus

- O. halli = Fremontella halli

- O. hamoculus = Mesonacis hamoculus

- O. hermani = Bolbolenellus hermani

- O. hyperboreus = Mesolenellus hyperboreus

- O. insolens = Bristolia insolens

- O. intermedius = Fritzolenellus lapworthi or F. reticulatus

- O. kentensis = Bolbolenellus groenlandicus

- O. lapworthi = Fritzolenellus lapworthi

- O. laxocules = Elliptocephala laxocules

- O. logani = Elliptocephala logani

- O. mickwitzi = Schmidtiellus mickwitzi mickwitzi

- O. mohavensis = Bristolia mohavensis

- O. multinodus = Nephrolenellus multinodus

- O. paraocules = Elliptocephala paraocules

- O. praenuntius = Elliptocephala praenuntius

- O. reticulatus = Fritzolenellus reticulatus

- O. sequomalus = Elliptocephala sequomalus

- O. sphaerulosus = Bolbolenellus sphaerulosus

- O. svalbardensis = Mesolenellus svalbardensis

- O. terranovicus = Mesonacis bonnensis

- O. torelli = Schmidtiellus mickwitzi torelli

- O. truemani[9] = Elliptocephala walcotti

- O. truemani[10] = Fritzolenellus truemani

- O. truncatooculatus = Mummaspis truncatooculatus

- O. vermontanus = Mesonacis vermontanus

- O. walcottanus = Wanneria walcottana

Distribution

O. thompsoni is found in the middle Upper Olenellus-zone of Vermont (Franklin County, Parker Slate, Georgia).[6]

O. agellus is present in the middle Upper Olenellus-zone of Vermont (Parker Slate, Georgia).[6]

O. chiefensis has been collected from the final layer of the Upper Olenellus-zone of Nevada (Pioche Formation).[3]

O. clarki is found in Upper Olenellus-zone of California (Bristol Mountain, near Cadiz, on the Santa Fé Railroad, 100 miles East of Barstow, Mohave Desert, probably Latham Shale;[11] Latham Shale – treated as the Bristolia-zonule – Marble Mountains, ½ mile East of Cadiz,[7] and at the Southern end of the Marble Mountains, near Chambless in the Mohave Desert portion of San Bernardino County, as well as from the Latham Shale, near Summit Springs on the West side of the Providence Mountains, San Bernardino County.[12] In California also from the Carrara Formation, Funeral Mountains, Resting Spring Range, Eagle mountain, Grapevine Mountains, Salt Spring Hills); and in Nevada (Nevada Test Site, Desert Range).

O. crassimarginatus has been collected in the middle Upper Olenellus-zone of Vermont (Parkers Quarry, Parker Slate, Georgia);[5] and ½ mile South of East Petersburg; 2 miles North of York and Fruitville, 3 miles North of Lancaster (all in the Kinzers Shale).

O. fowleri has been collected from the final layer of the Upper Olenellus-zone of Nevada (Pioche Formation).[3]

O. getzi is found in Upper Olenellus-zone of Pennsylvania (2 miles North of York, and Noah Getz Farm, 1 mile North of Rohrerstown, Kinzers Shale).[13]

O. howelli occurs in the final layer of the Upper Olenellus-zone of Nevada (Pioche Formation).[3]

O. nevadensis has been collected in the Upper Olenellus-zone, Bristolia-zonule of California (Carrara Formation, Funeral Mountains and Grapevine Mountains); and from the Latham Shale – treated as the Bristolia-zonule – at the South end of the Marble Mountains, near Chambless in the Mohave Desert portion of San Bernardino County.[12] It also occurs in the Bristolia-zonule, Upper Olenellus-zone of Nevada (Carrara Formation, Desert Range, Locality M-5).

O. parvifrontatus has been collected in the Olenellus-zone of the Yukon Territory, Canada (Unit 6 of the Upper Illtyd Formation, Wernecke Mountains).[14]

O. puertoblancoensis was found in the Botonian/Toyonian Olenellus-zone of the Caborca Region, Mexico (Buelna Formation, Cerro Rajon)[15]

O. robsonensis occurs in the ?Middle Olenellus-zone of British Columbia, Canada (?Upper Mahto Formation, drift block on the slope of the Mural Glacier below Mumm Peak, Near Mount Robson).[16]

O. roddyi occurs in the Olenellus-zone of Pennsylvania (2 miles North of York, Fruitville; 3 miles North of Lancaster; Getz Quarry; 1 mile North of Rohrerstown; ½ mile South of East Petersburg; all in the Kinzers Shale).[6]

O. romensis occurs in the middle Upper Olenellus-zone of Virginia (Rome Formation, Mason Creek, Salem;[8][17][18] North-East of Roanoke, near Webster; 2 miles South-West of Blue Ridge Springs, 2 miles South of Max Meadows; Mason Creek, 1 mile east of Salem; ½ mile South-East of Indian Rock; 1 mile East of Cleveland, Alabama; 1½ miles North of Montevallo; 1½ miles West of Montevallo).[19][20]

O. terminatus has been collected from the final layer of the Upper Olenellus-zone of Nevada (Pioche Formation).[3]

O. transitans has been collected from the middle Upper Olenellus-zone of Vermont (Parker Slate, Georgia).[6]

Description

As with most early trilobites, Olenellus has an almost flat exoskeleton, that is only thinly calcified, and has crescent-shaped eye ridges. As part of the suborder Olenellina, Olenellus lacks dorsal sutures. Like all other members of the superfamily Olenelloide, the eye-ridges emerge from the back of the frontal lobe (L4) of the central area of the cephalon, that is called glabella. Olenellus also shares the typical character of whole family Olenellidae that the frontal (L3) and middle pair (L2) of lateral lobes of the glabella are partially merged. This creates two very typical, isolated slits. It can be distinguished from the other two genera in the family, Mesolenellus and Mesonacis, because the angle in the back rim of the cephalon is less than 15°, making the head approximately semi-circular. The genal spines are reaching back no further than the 6th thorax segment, making them 4-5 times as long as the most backward lobe of the glabella (occipital ring or L0)1. The thorax is 4-4½ times wider that the axis, measured at the 3rd segment. The base of the spine on the 15th thorax segment is almost as wide as the axis itself.[1]

Key to the species

This key is based on Lieberman (1999), which describes only part of the species that are recognized today.

| 1 | Frontal lobe of the glabella (L4) rounded. → 2 |

|---|---|

| - | L4 pointed anteriorly. → Olenellus chiefensis |

| 2 | The frontal lobe of the glabella (L4) is connected with the border surrounding the cephalon with a short ridge on the midline (the so-called “plectrum”). → 3 |

| - | Plectrum absent. → 8 |

| 3 | Frontal lobe of the glabella (L4) as wide as, or narrower than, the occipital ring (L0). → 4 |

| - | L4 wider than L0. → Olenellus agellus |

| 4 | Ocular lobe with a prominent furrow along the entire margin. → 5 |

| - | Furrow only present at the anterior margin of the ocular lobe. → 7 |

| 5 | The area outside the eye lobe (or extraocular area) is prominently flattened. The frontal margin of the third thorax segment (T3) is deflected anteriorly between 0% and 10%. The eye lobe extends backward to the middle of the occipital ring (L0) or the furrow (S0) between the occipital ring (L0) and the most backward pair of side lobes (L1). → 6 |

| - | The area outside the eye lobe (or extraocular area) is gently convex. The frontal margin of T3 is deflected anteriorly between 5% and 10%. The eye lobe extends backward to the middle of L0. → Olenellus roddyi |

| 6 | The maximum width of the frontal lobe of the glabella (L4) is more than 80% of the maximum width of the backward most lobe (L0). The area in front of the glabella (or preglabellar field) is between 15% and 25% of the length of L4. The right and left furrow (S2) between the second (L2) and third (L3) pair of side lobes (counted from the back of the cephalon) may or may not join across the midline. The eye lobe extends backward to the furrow (S0) between L0 and the most backward pair of side lobes (L1). → Olenellus clarki |

| - | The maximum width of L4 is less than 80% of the maximum width of L0. The area in front of the glabella (or preglabellar field) is between 15% and 50% of the length of L4. The right and left S2-furrow join across the midline. The eye lobe extends backward to the middle of L0 or S0. → Olenellus nevadensis |

| 7 | The right and left furrow (S1) between the first (L1) and second (L2) pair of side lobes (counted from the back of the cephalon) join across the midline. The area outside the eye lobe (or extraocular area) is prominently flattened. The frontal margin of the third thorax segment (T3) is deflected anteriorly between 5% and 10%. → Olenellus transitans |

| - | The right and left part of S1 do not join across the midline. The area outside the eye lobe (or extraocular area) is gently convex. The frontal margin of T3 is deflected anteriorly between 0% and 5%. → Olenellus parvofrontatus |

| 8 | The eye lobe extends backward to the furrow (S0) between the occipital ring (L0) and the most backward pair of side lobes (L1). → 9 |

| - | The eye lobe extends backward to the middle of L0. → 10 |

| 9 | The maximum width of the frontal lobe of the glabella (L4) is larger than the maximum width of the occipital ring (L0). L2 bulges laterally compared to L0. The pleural spines of the third thorax segment (T3) extend backwards the entire length of the prothorax. The width of the seventh thorax segment (T7) is more than ⅔ of the width of T3, excluding the spines. → Olenellus romensis |

| - | The maximum width of L4 is smaller than, or approximately equal to, the maximum width of L0. L2 is as wide as L0. The pleural spines of T3 extend backwards 6 to 8 segments. The width of T7 is less than ⅔ of the width of T3, excluding the spines. → Olenellus getzi |

| 10 | The maximum width of the frontal lobe of the glabella (L4) is larger than the maximum width of the occipital ring (L0). L2 bulges laterally compared to L0. → Olenellus thompsoni |

| - | The maximum width of L4 is approximately equal to the maximum width of L0. L2 bulges laterally compared to L0. → Olenellus robsonensis |

| - | The maximum width of L4 is smaller than the maximum width of L0. L2 is as wide as L0. → Olenellus crassimarginatus |

References

- Lieberman, B.S. (1999). "Systematic Revision of the Olenelloidea (Trilobita, Cambrian)" (PDF). Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 45.

- Cowie, J.; McNamara, K.J. (1978). "Olenellus (Trilobita) from the Lower Cambrian Strata of North-West Scotland" (PDF). Palaeontology. 21 (3): 615–634.

- Palmer, A.R. (1998). "Terminal Early Cambrian Extinction of the Olenellina: Documentation from the Pioche Formation, Nevada". Journal of Paleontology. 72 (4): 650–672. doi:10.1017/S0022336000040373. JSTOR 1306693.

- W. H. Fritz (1995). "Esmeraldina rowei and associated Lower Cambrian trilobites (1f fauna) at the base of Walcott's Waucoban Series, Southern Great Basin, U.S.A.". Journal of Paleontology. 69 (4): 708–723. doi:10.1017/S002233600003523X. JSTOR 1306305.

- Walcott, C.D. (1910), "Olenellus and other genera of the Mesonacidae", Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 63 (6): 231–422

- Palmer, A.R.; Repina, L.N. (1993), "Through a Glass Darkly: Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Biostratigraphy of the Olenellina", The University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions, 3: 1–35

- Riccio, J.F. (1952), "The Lower Cambrian Olenellidae of the Marble Mountains, California", Bulletin of the Californian Academy of Sciences, 51: 25–49

- Resser, C.E.; Howell, B.F. (1938), "Lower Cambrian Olenellus zone of the Appalachians", Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, 49 (2): 195–248, doi:10.1130/GSAB-49-195

- Fritz, W.H. (1972), "Lower Cambrian Trilobites from the Sekwi Formation type section, Mackenzie Mountains, northwestern Canada", Bulletin of the Canadian Geological Survey, 212: 1–90

- Walcott, C.D. (1913), "Cambrian geology and paleontology, No. 11, New Lower Cambrian subfauna", Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 67 (11): 309–326

- Resser, C.E. (1928), "Cambrian Fossils from the Mohave Desert", Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 81 (2): 1–14

- Hazzard, J.C.; Crickmay, C.H. (1933), "Notes on the Cambrian rocks of the eastern Hohave Desert, California", University of California Publications, Bulletin of the Department of Geological Science

- Dunbar, C.O. (1925), "Antennae in Olenellus getzi, n.sp.", American Journal of Science, 5 (9): 303–308, doi:10.2475/ajs.s5-9.52.303

- Fritz, W.H. (1991), "Lower Cambrian Trilobites from the Illtyd Formation, Wernecke Mountains, Yukon Territoriy", Bulletin of the Geological Survey of Canada, 409: 1–77

- Stewart, J.; McMenamin, M. A. S.; Morales-Ramirez, J. M. (1984), "Upper Proterozoic and Cambrian rocks in the Caborca Region, Sonora, Mexico - physical stratigraphy, biostratigraphy, paleocurrent studies, and regional relations", U.S. Geological Survey Professional Papers, 1309: 1–33

- Fritz, W.H. (1992), "Walcott's Lower Cambrian olenellid trilobite collection 61K, Mount Robson area, Canadian Rocky Mountains", Bulletin of the Canadian Geological Survey, 432: 1–65

- Stose, G.W.; Jonas, A.I. (1922), "The lower Paleozoic section in southeastern Pennsylvania: Washington", Journal of the Academy of Sciences, 12 (5): 358–366

- Taylor, J.F.; Durika, N.J. (1990), Lithofacies, trilobite faunas, and correlation of the Kinzers, Ledger, and Conestoga Formations in the Conestoga Valley [Chapter IX] In: Carbonates, schists, and geomorphology in the vicinity of the lower reaches of the Susquehanna River; 55th annual field conference of Pennsylvania geologists: Field Conference of Pennsylvania Geologists, no. 55, p. 136-160.

- Rankin, D.W.; Drake Jr., A.A.; Glover III, L.; Goldsmith, R.; Hall, L.M.; Murray, D.P.; Ratcliffe, N.M.; Read, R.F.; Secor Jr., D.T.; Stanley, R.S. (1989), Pre-orogenic terrains In: R.D. Hatcher, W.A. Thomas, and G.W. Viele, eds. The Appalachian-Ouachita Orogen in the United States. The Geology of North America, Volume F-2. Boulder CO. Geological Society of America: pp. 7-101.

- Barnaby, R.J.; Read, J.F. (1990), "Carbonate ramp to rimmed shelf evolution: Lower to Middle Cambrian continental margin, Virginia Appalachians", Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, 102 (3): 391–404, doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1990)102<0391:crtrse>2.3.co;2