Okefenokee Swamp

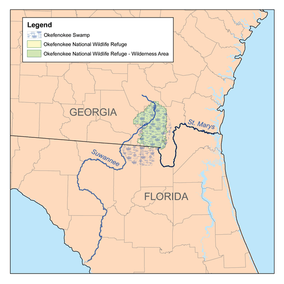

The Okefenokee Swamp is a shallow, 438,000-acre (177,000 ha), peat-filled wetland straddling the Georgia–Florida line in the United States. A majority of the swamp is protected by the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge and the Okefenokee Wilderness. The Okefenokee Swamp is considered to be one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Georgia. The Okefenokee is the largest "blackwater" swamp in North America.

| Okefenokee Swamp | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Southern Georgia Northern Florida |

| Coordinates | 30°37′N 82°19′W |

| Area | 438,000 acres (1,770 km2) |

| Designated | 1974 |

The swamp was designated a National Natural Landmark in 1974.[1]

Etymology

The name Okefenokee is attested with more than a dozen variant spellings of the word in historical literature. Though often translated as "land of trembling earth", the name is likely derived from Hitchiti oki fanôːki "bubbling water".[2]

Origin

The Okefenokee was formed over the past 6,500 years by the accumulation of peat in a shallow basin on the edge of an ancient Atlantic coastal terrace, the geological relic of a Pleistocene estuary. The swamp is bordered by Trail Ridge, a strip of elevated land believed to have formed as coastal dunes or an offshore barrier island. The St. Marys River and the Suwannee River both originate in the swamp. The Suwannee River originates as stream channels in the heart of the Okefenokee Swamp and drains at least 90 percent of the swamp's watershed southwest toward the Gulf of Mexico. The St. Marys River, which drains only 5 to 10 percent of the swamp's southeastern corner, flows south along the western side of Trail Ridge, through the ridge at St. Marys River Shoals, and north again along the eastern side of Trail Ridge before turning east to the Atlantic.

History

The earliest known inhabitants of the Okefenokee Swamp were the Timucua-speaking Oconi, who dwelt on the eastern side of the swamp. The Spanish friars built the mission of Santiago de Oconi nearby in order to convert them to Christianity. The Oconi's boating skills, developed in the hazardous swamps, likely contributed to their later employment by the Spanish as ferrymen across the St. Johns River, near the riverside terminus of North Florida's camino real.[3]

Modern-day longtime residents of the Okefenokee Swamp, referred to as "Swampers", are of overwhelmingly English ancestry. Due to relative isolation, the inhabitants of the Okefenokee used Elizabethan phrases and syntax, preserved since the early colonial period when such speech was common in England, well into the 20th century.[4] The Suwannee Canal was dug across the swamp in the late 19th century in a failed attempt to drain the Okefenokee. After the Suwannee Canal Company's bankruptcy, most of the swamp was purchased by the Hebard family of Philadelphia, who conducted extensive cypress logging operations from 1909 to 1927. Several other logging companies ran railroad lines into the swamp until 1942; some remnants remain visible crossing swamp waterways. On the west side of the swamp, at Billy's Island, logging equipment and other artifacts remain of a 1920s logging town of 600 residents. Most of the Okefenokee Swamp is included in the 403,000-acre (163,000 ha) Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge.

A wildfire begun by a lightning strike near the center of the refuge on May 5, 2007, eventually merged with another wildfire that began near Waycross, Georgia, on April 16 when a tree fell on a power line. By May 31, more than 600,000 acres (240,000 ha), or more than 935 square miles, had burned in the region.[5][6]

In 2011, the Honey Prairie Fire consumed 309,200 acres (125,100 ha) of land in the Swamp.[7]

Access

There are four public entrances:

- Suwannee Canal Recreation Area at Folkston, Georgia

- Kingfisher Landing at Race Pond, Georgia

- Stephen C. Foster State Park at Fargo, Georgia

- Suwannee Sill Recreation Area at Fargo, Georgia

In addition, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, Okefenokee Swamp Park, provides the northern most access into the Okefenokee Swamp near Waycross, Georgia.

State Road 2 passes through the Florida portion between the Georgia cities of Council and Moniac.

The graded Swamp Perimeter Road encircles Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. Gated and closed to public use, it provides access for fire management of the interface between the federal refuge and the surrounding industrial tree farms.

Tourism

Many visitors enter the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge each year. The swamp provides an important economic resource to southeast Georgia and northeast Florida. About 400,000 people visit the swamp annually, with many from distant locations such as Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Japan, China and Mexico. Service providers at the refuge entrances and several local outfitters offer guided tours by motorboat, canoe, and kayak.

DuPont titanium mining operation

A 50-year titanium mining operation by DuPont was set to begin in 1997, but protests and public–government opposition over possibly disastrous environmental effects from 1996 to 2000 forced the company to abandon the project in 2000 and retire their mineral rights forever. In 2003, DuPont donated the 16,000 acres (6,500 ha) it had purchased for mining to The Conservation Fund, and in 2005, nearly 7,000 acres (2,800 ha) of the donated land was transferred to Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge.

Environment

The Okefenokee Swamp is part of the Southeastern conifer forests ecoregion. Much of the Okefenokee is a southern coastal plain nonriverine basin swamp, forested by bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) and swamp tupelo (Nyssa biflora) trees. Upland areas support southern coastal plain oak domes and hammocks, thick stands of evergreen oaks. Drier and more frequently burned areas support Atlantic coastal plain upland longleaf pine woodlands of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris).[8]

The swamp has many species of carnivorous plants, including many species of Utricularia, Sarracenia psittacina, and the giant Sarracenia minor var. okefenokeensis.

The Okefenokee Swamp is home to many wading birds, including herons, egrets, ibises, cranes, and bitterns, though populations fluctuate with seasons and water levels. The swamp also hosts numerous woodpecker and songbird species.[9] Okefenokee is famous for its amphibians and reptiles such as toads, frogs, turtles, lizards, snakes, and an abundance of American alligators. It is also a critical habitat for the Florida black bear.

In 1974, two LP recordings of the sounds of the swamp were released as disk 6 of the Environments series.

Recent events

More than 600,000 acres (240,000 ha) of the Okefenokee region burned from April to July 2007. Essentially the entire swamp burned, but the degrees of impact are widely varied. Smoke from the fires was reported as far away as Atlanta and Orlando.

Four years later, in April 2011, the Honey Prairie wildfire began when the swamp was left much drier than usual by an extreme drought. As of January 2012, the Honey Prairie fire had already scorched more than 315,000 acres (127,000 ha) of the 438,000-acre (177,000 ha) Okefenokee, sending volumes of smoke across the southern Atlantic seaboard and with an unknown impact on wildlife. With the drought still continuing, the massive Honey Prairie fire continued to burn at only 75% containment.[10] On April 17, 2012, the Honey Prairie Fire was finally declared out. Thousands of firefighters, refuge neighbors, and businesses contributed to the safe suppression of this fire. At the peak of fire activity on June 27, 2011, the Honey Prairie Complex had grown to 283,673 acres (114,798 ha) and had 202 engines, 112 dozers, 20 water tenders, 12 helicopters, and 6 crews with a total of 1,458 personnel assigned. Over the duration of the fire, there were no fatalities or serious injuries. Firefighters managed to contain the fire within the boundaries of the 402,000 acre Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. Only 18,206 acres (7,368 ha) burned outside the refuge.[11]

On April 6, 2017, a lightning strike started the West Mims Fire,[12] which burned about 152,000 acres (62,000 ha).[13]

In popular culture

- The name "Okefenokee" has appeared many times in American pop culture, including Walt Kelly's comic strip Pogo, where the characters made their home in the Okefenokee Swamp, and Scooby-Doo, in which Scooby-Dum comes from the Okefenokee as well.

- The 1941 movie Swamp Water, directed by Jean Renoir, starring Walter Brennan and Walter Huston, and based on the novel by Vereen Bell, was shot on location in the Okefenokee near Waycross, Georgia.

- The 1952 movie Lure of the Wilderness, a remake of Swamp Water starring Jeffrey Hunter, Walter Brennan (reprising his Swamp Water role), and Jean Peters, was set in the Okefenokee Swamp[14]

- in 1962, Los Angeles sisters Jonell and Glenell McQuaig, known as "The Holly Twins," recorded an atmospheric song with swamp creature sound effects, "Okeefenokee."[15]

- The former Six Flags Over Georgia attraction "Tales of the Okefenokee: The Old Plantation Legends" is named after the swamp.

- The Okefenokee Swamp is considered to be one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Georgia.

- in 1973, the Okefenokee was mentioned in the Hollywood film White Lightning starring Burt Reynolds as Robert 'Gator' McKlusky, an illegal moonshine runner. Reynolds reprised the role in the 1976 sequel Gator, also his directorial debut. The film co-starred celebrated Georgia Swamp Rock musician/actor Jerry Reed, who wrote and recorded "The Ballad of Gator McKlusky" for the film.[16]

- The third track on the 1976 album Stratosfear by Tangerine Dream is called "3 AM at the Border of the Marsh from Okefenokee"

References

- "Okefenokee Swamp". nps.gov. National Park Service.

- Handbook of North American Indians: Languages. Government Printing Office. January 1, 1978. p. 191. ISBN 9780160487743.

hitchiti okefenokee.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (August 14, 1996). Timucua. VNR AG. pp. 50, 202. ISBN 9781557864888.

- Matschat, Cecile Hulse (1938). Suwanee River: Strange Green Land. University of Georgia Press. p. 7.

- "Georgia Forestry Commission Home Page". Gatrees.org. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- "Massive Blaze In S.E. Georgia Jumps Fire Lines". Jacksonville, Florida: WJXT-TV. May 25, 2007. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- "InciWeb: Honey Prairie Complex". InciWeb. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- United States Geological Survey. "Land Cover Viewer" (Map). National Gap Analysis Program. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- "Bird Checklists of the United States: Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge". US Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- "Honey Prairie Complex". InciWeb Incident Information system. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

"Honey Prairie Complex Fires". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

"Okefenokee's birds undeterred by fires". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved February 2, 2012. - http://www.fws.gov/okefenokee/PDF/honey%20prairie%20fire%20declared%20out.pdf%5B%5D

- "South Georgia wildfire forces evacuations; ash reaches Jacksonville". Atlanta Journal Constitution. May 19, 2017. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- "GA Firefighters Report Progress Against West Mims Fire In Okefenokee". Firefighter News. May 19, 2017. Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- "'Lure of the Wilderness'". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- "The Holly Twins discography". RateYourMusic. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "The Ballad Of Gator Mcklusky lyrics - Jerry Reed original song - full version on Lyrics Freak". www.lyricsfreak.com. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

Bibliography

- Afable, Patricia O. & Beeler, Madison S. (1996). "Place Names". In Goddard, Ives & Sturtevant, William C. (eds.). Handbook of North American Indians. Volume 17: Languages. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Worth, John E. (1998). Timucua Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida. Volume 2: Resistance and Destruction. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1574-X. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- Nelson, Megan Kate (2005). Trembling Earth: A Cultural History of the Okefenokee Swamp. Athens: University of Georgia Press. This is a readable book from a professional historian that covers the history of the human interaction with the swamp from about 1700 to the 1940s, very good background for those planning a visit.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Okefenokee Swamp. |

- GeorgiaEncyclopedia.org: Natural History of the Okefenokee Swamp

- FWS.gov: Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge website

- Gorp.com: Okefenokee Swamp and National Wildlife Refuge

- Okefenokee Adventures website

- Okefenokee Pastimes website

- Okefenokee Swamp parks website

- Okefenokee Nation website

- Charlton County: Okefenokee Swamp historical marker