Apalachicola River

The Apalachicola River /æpəlætʃɪˈkoʊlə/ is a river, approximately 160 mi (180 km) long in the state of Florida. The river's large watershed, known as the ACF River Basin, drains an area of approximately 19,500 square miles (50,505 km2) into the Gulf of Mexico. The distance to its farthest head waters in northeast Georgia is approximately 500 miles (800 km). Its name comes from the Apalachicola people, who used to live along the river.[1]

| Apalachicola River | |

|---|---|

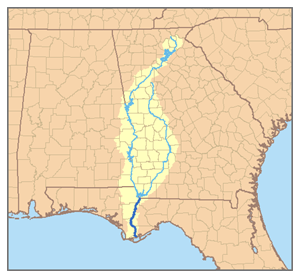

Map of the Apalachicola River watershed showing the two main tributaries, the Chattahoochee River (left) and the Flint River (right). | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Confluence of Chattahoochee River and Flint River at Chattahoochee, Florida |

| • elevation | 77 feet (23 m) |

| Mouth | |

• location | Gulf of Mexico at Apalachicola, Florida |

| Length | 160 miles (260 km) |

| Basin size | 19,500 sq mi (50,505 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 19,602 cu ft/s (555.1 m3/s) |

Description

The river is formed on the state line between Florida and Georgia, near the town of Chattahoochee, Florida, approximately 60 miles (97 km) northeast of Panama City, by the confluence of the Flint and Chattahoochee rivers. The actual confluence is contained within the Lake Seminole reservoir formed by the Jim Woodruff Dam. It flows generally south through the forests of the Florida Panhandle, past Bristol. In northern Gulf County, it receives the Chipola River from the west. It flows into Apalachicola Bay, an inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, at Apalachicola. The lower 30 mi (48 km) of the river is surrounded by extensive swamps and wetlands, except at the coast.

The watershed contains nationally significant forests, with some of the highest biological diversity east of the Mississippi River[2][3] and rivaling that of the Great Smoky Mountains. It has significant areas of temperate deciduous forest as well as longleaf pine landscapes and flatwoods. Flooded areas have significant tracts of floodplain forest.[4] All of these southeastern forest types were devastated by logging between 1880 and 1920,[5] and the Apalachiola contains some of the finest remaining examples of old growth forest in the southeast. The endangered tree species Florida torreya is endemic to the region; it clings to forested slopes and bluffs in Torreya State Park along the east bank of the river. The highest point within the watershed is Blood Mountain at 4,458 ft (1,359 m), near the headwaters of the Chattahoochee River.

Where the river enters the Gulf of Mexico it creates a rich array of wetlands varying in salinity. These include tidal marshes and seagrass meadows. Over 200,000 acres of this diverse delta complex are included within the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve.[6] There are also dunes with coastal grasslands and interdunal swales.

The basin of the Apalachicola River is also noted for its tupelo honey, a high-quality monofloral honey, which is produced wherever the tupelo trees bloom in the southeastern United States. In a good harvest year, the value of the tupelo honey crop produced by a group of specialized Florida beekeepers approaches $900,000 each spring.[7]

During Florida's British colonial period, the river formed the boundary between East Florida and West Florida.

Geologically, the river links the coastal plain and Gulf Coast with the Appalachian Mountains.[8]

Some of the remaining important areas of natural habitat along the river include Apalachicola National Forest, Torreya State Park, The Nature Conservancy Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve, Tates Hell State Forest, and Apalachicola River Wildlife and Environmental Area, as well as the Apalachicola River Water Management Area. It has been suggested that this watershed should be nationally ranked and appreciated as being as significant as the Everglades or Great Smoky Mountains.[3] To raise awareness about the importance of preserving the natural state of the river and its inhabitants, Florida film producer Elam Stoltzfus highlighted this system in a PBS documentary in 2006.[9]

The river forms the boundary between the Eastern and Central time zones in Florida, until it reaches the Jackson River. Thereafter, the Jackson River, which flows to the Gulf of Mexico, is the time zone boundary.[10]

List of crossings

| Crossing | Carries | Location | Coordinates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jim Woodruff Dam | Chattahoochee | |||

| Victory Bridge | Chattahoochee | |||

| Rail bridge | CSX Transportation | Chattahoochee | ||

| Dewey M. Johnson Bridge | Marianna to Quincy | |||

| Trammell Bridge | Bristol | |||

| Rail bridge | Apalachicola Northern Railway | Apalachicola | ||

| John Gorrie Memorial Bridge | Apalachicola |

See also

- List of Florida rivers

- South Atlantic-Gulf Water Resource Region

- Voices of the Apalachicola

References

- Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- White, P.S., S.P. Wilds, and G.A. Thunhorst. 1998. Southeast. Pp. 255–314, In M.J. Mac, P.A. Opler, C.E. Puckett Haecker, and P.D. Doran (Eds.). Status and Trends of the Nation's Biological Resources. 2 vols. US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey, Reston, VA.

- Keddy, Paul A. (1 July 2009). "Thinking Big: A Conservation Vision for the Southeastern Coastal Plain of North America". Southeastern Naturalist. 8 (2): 213–226. doi:10.1656/058.008.0202.

- Messina, M.G. and W. H. Conner.(eds) 1998. Southern Forested Wetlands: Ecology and Management. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, FL: .

- Williams, M. 1989. The lumberman's assault on the southern forest, 1880–1920. Pp. 238–288, In M. Williams (ed.). Americans and Their Forests: A Historical Geography. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- "Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve". Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090319130345/http://impact.ifas.ufl.edu/impact_sum_2001.pdf, p. 19

- Delcourt, H. R. and P. A. Delcourt. 1991. Quaternary Ecology: A Paleoecological Perspective. London: Chapman and Hall.

- http://www.apalachicolaamericantreasure.com

- 49 C.F.R. § 71.5(f).

Further reading

- White, P.S., S.P. Wilds, and G.A. Thunhorst. 1998. Southeast. Pp. 255–314, In M.J. Mac, P.A. Opler, C.E. Puckett Haecker, and P.D. Doran (Eds.). "Status and Trends of the Nation’s Biological Resources". 2 vols. US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey, Reston, VA.

- Boyce, S.G., and W.M. Martin. 1993. The future of the terrestrial communities of the southeastern United States. Pp. 339–366, In W.H. Martin, S.G. Boyce, and A.C. Echternacht (Eds.). Biodiversity of the Southeastern United States, Lowland Terrestrial Communities. Wiley, New York, NY.

- Light, H.M., M.R. Darst, and J.W. Grubbs. (1998). Aquatic habitats in relation to river flow in the Apalachicola River floodplain, Florida [U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1594]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apalachicola River. |

- Florida State University: Apalachicola River Ecological Management Plan

- Apalachicola River Watershed – Florida DEP

- Apalachicola River Wildlife and Environmental Area

- Apalachicola Riverkeeper, an organization focused on the protection of the Apalachicola

- National Estuarine Research Reserve

- Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve, a Nature Conservancy preserve

- Northwest Florida Water Management District

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Flint-Chatahoochee-Apalachicola basin

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Apalachicola River