Cistercians

The Cistercians (/sɪˈstɜːrʃənz/)[1] officially the Order of Cistercians (Latin: (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. They are also known as Bernardines, after the highly influential Bernard of Clairvaux (though that term is also used of one of the Franciscan Orders in Poland and Lithuania); or as White Monks, in reference to the colour of the "cuccula" or white choir robe worn by the Cistercians over their habits, as opposed to the black cuccula worn by Benedictine monks.

(Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis | |

Coat of arms of the Cistercians | |

| Abbreviation | OCist or SOCist |

|---|---|

| Motto | Cistercium mater nostra "Cîteaux is our mother" |

| Formation | 1098 |

| Founder | Robert of Molesme, Stephen Harding, and Alberic of Cîteaux |

| Founded at | Cîteaux Abbey |

| Type | Catholic religious order |

| Headquarters | Piazza del Tempio di Diana, 14 Rome, Italy |

Abbot General | Mauro Giorgio Giuseppe Lepori |

Parent organization | Catholic Church |

| Website | www |

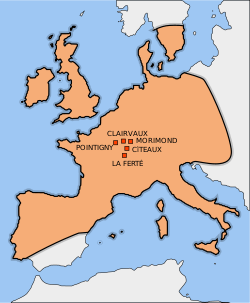

.jpg)

The term Cistercian (French Cistercien), derives from Cistercium,[2] the Latin name for the village of Cîteaux, near Dijon in eastern France. It was in this village that a group of Benedictine monks from the monastery of Molesme founded Cîteaux Abbey in 1098, with the goal of following more closely the Rule of Saint Benedict. The best known of them were Robert of Molesme, Alberic of Cîteaux and the English monk Stephen Harding, who were the first three abbots. Bernard of Clairvaux entered the monastery in the early 1110s with 30 companions and helped the rapid proliferation of the order. By the end of the 12th century, the order had spread throughout what is today France, Germany, England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Scandinavia and Eastern Europe.

The keynote of Cistercian life was a return to literal observance of the Rule of St Benedict. Rejecting some of the developments the Benedictines had undergone, the monks tried to live monastic life as it had been in Saint Benedict's time; indeed in various points they went beyond it in austerity. The most striking feature in the reform was the return to manual labour, especially agricultural work in the fields, a special characteristic of Cistercian life.[3] The Cistercians also made major contributions to culture and technology in medieval Europe: Cistercian architecture is considered one of the most beautiful styles of medieval architecture;[4] and the Cistercians were the main force of technological diffusion in fields such as agriculture, hydraulic engineering.

The original emphasis of Cistercian life was on manual labour and self-sufficiency, and many abbeys have traditionally supported themselves through activities such as agriculture and brewing ales. Over the centuries, however, education and academic pursuits came to dominate the life of many monasteries. A reform movement seeking a simpler lifestyle began in 17th-century France at La Trappe Abbey, and became known as the Trappists. The Trappists were eventually consolidated in 1892 into a new order called the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (Latin: Ordo Cisterciensis Strictioris Observantiae), abbreviated as OCSO.[5] The Cistercians who did not observe these reforms and remained within the Order of Cistercians and are sometimes called the Cistercians of the Common Observance when distinguishing them from the Trappists.

History

Foundation

In 1098, a Benedictine abbot, Robert of Molesme, left Molesme Abbey in Burgundy with around 20 supporters, who felt that the Cluniac communities had abandoned the rigours and simplicity of the Rule of St. Benedict.[6] On 21 March 1098, Robert's small group acquired a plot of marshland just south of Dijon called Cîteaux (Latin: "Cistercium". Cisteaux means reeds in Old French), given to them expressly for the purpose of founding their Novum Monasterium.[7]

Robert's followers included Alberic, a former hermit from the nearby forest of Colan, and Stephen Harding, a member of an Anglo-Saxon noble family which had been ruined as a result of the Norman conquest of England.[6] During the first year, the monks set about constructing lodging areas and farming the lands of Cîteaux, making use of a nearby chapel for Mass. In Robert's absence from Molesme, however, the abbey had gone into decline, and Pope Urban II, a former Cluniac monk, ordered him to return.[8]

The remaining monks of Cîteaux elected Alberic as their abbot, under whose leadership the abbey would find its grounding. Robert had been the idealist of the order, and Alberic was their builder. Upon assuming the role of abbot, Alberic moved the site of the fledgling community near a brook a short distance away from the original site. Alberic discontinued the use of Benedictine black garments in the abbey and clothed the monks in white habits of undyed wool.[9] He returned the community to the original Benedictine ideal of manual work and prayer, dedicated to the ideal of charity and self sustenance. Alberic also forged an alliance with the Dukes of Burgundy, working out a deal with Duke Odo I of Burgundy concerning the donation of a vineyard (Meursault) as well as stones with which they built their church. The church was consecrated and dedicated to the Virgin Mary on 16 November 1106, by the Bishop of Chalon sur Saône.[10]

On 26 January 1108, Alberic died and was soon succeeded by Stephen Harding, the man responsible for carrying the order into its crucial phase.

Cistercian reform

_-_Diogo_de_Contreiras.png)

The order was fortunate that Stephen was an abbot of extraordinary gifts, and he framed the original version of the Cistercian "Constitution" or regulations: the Carta Caritatis (Charter of Charity). Although this was revised on several occasions to meet contemporary needs, from the outset it emphasised a simple life of work, love, prayer and self-denial. The Cistercians initially regarded themselves as regular Benedictines, albeit the "perfect", reformed ones, but they soon came to distinguish themselves from the monks of unreformed Benedictine communities by wearing white tunics instead of black, previously reserved to hermits, who followed the "angelic" life. Cistercian abbeys also refused to admit boy recruits, a practice later adopted by many of older Benedictine houses.[11]

Stephen acquired land for the abbey to develop to ensure its survival and ethic, the first of which was Clos Vougeot. As to grants of land, the order would accept only undeveloped land, which the monks then developed by their own labour. For this they developed over time a very large component of uneducated lay brothers known as conversi.[12] In some cases, the Order accepted developed land and relocated the serfs elsewhere.[11] Stephen handed over the west wing of Cîteaux to a large group of lay brethren to cultivate the farms. These lay brothers were bound by vows of chastity and obedience to their abbot, but were otherwise permitted to follow a form of Cistercian life that was less intellectually demanding. Their incorporation into the order represents a compassionate outreach to the illiterate peasantry, as well as a realistic recognition of the need for additional sources of labour to tackle "unmanorialized" Cistercian lands.[13]

Charter of Charity

The outlines of the Cistercian reform were adumbrated by Alberic, but it received its final form in the Carta caritatis (Charter of Charity), which was the defining guide on how the reform was to be lived.[14][15] This document governed the relations between the various houses of the Cistercian order, and exercised a great influence also upon the future course of western monachism. From one point of view, it may be regarded as a compromise between the primitive Benedictine system, in which each abbey was autonomous and isolated, and the complete centralization of Cluny, where the Abbot of Cluny was the only true superior in the entire Order.[3]

The Cistercian order maintained the independent organic life of the individual houses: each abbey having its own abbot elected by its own monks, its own community belonging to itself and not to the order in general, and its own property and finances administered without outside interference. Yet on the other hand, all the abbeys were subjected to the General Chapter, the constitutional body which exercised vigilance over the Order. Made up of all the abbots, the General Chapter met annually in mid-September at Cîteaux. Attendance was compulsory, and absence without leave was severely punished. The Abbot of Cîteaux presided over the chapter.[16] He had a predominant influence and the power of enforcing everywhere exact conformity to Cîteaux in all details of the exterior life observance, chant, and customs. The principle was that Cîteaux should always be the model to which all the other houses had to conform. In case of any divergence of view at the chapter, the opinion espoused by the Abbot of Cîteaux always prevailed.[17]

High and Late Middle Ages

Spread: 1111–52

By 1111 the ranks had grown sufficiently at Cîteaux, and Stephen sent a group of 12 monks to start a "daughter house", a new community dedicated to the same ideals of the strict observance of Saint Benedict. The Cistercians were officially formed in 1112.[18] The "daughter house" was built in Chalon sur Saône in La Ferté on 13 May 1113.[19]

In the year of 1112, a charismatic young Burgundinian nobleman named Bernard arrived at Cîteaux with 35 of his relatives and friends to join the monastery. A supremely eloquent, strong-willed mystic, Bernard was to become the most admired churchman of his age.[13] In 1115, Count Hugh of Champagne gave a tract of wild, afforested land known as a refuge for robbers, forty miles east of Troyes, to the order. Bernard led twelve other monks to found the Abbey of Clairvaux, and began clearing the ground and building a church and dwelling.[20] The abbey soon attracted a strong flow of zealous young men.[21] At this point, Cîteaux had four daughter houses: Pontigny, Morimond, La Ferté and Clairvaux. Other French daughter houses of Cîteaux would include Preuilly, La Cour-Dieu, Bouras, Cadouin and Fontenay.

With Saint Bernard's membership, the Cistercian order began a notable epoch of international expansion; and as his fame grew, the Cistercian movement grew with it.[13] In November 1128, with the aid of William Giffard, Bishop of Winchester, Waverley Abbey was founded in Surrey, England. Five houses were founded from Waverley Abbey before 1152, and some of these had themselves produced offshoots.[4]

In 1129 Margrave Leopold the Strong of Styria called upon the Cistercians to develop his recently acquired March which bordered Austria on the south. He granted monks from the Ebrach Abbey in Bavaria an area of land just north of what is today the provincial capital Graz, where they founded Rein Abbey. At the time, it was the 38th Cistercian monastery founded but, due to the dissolution down the centuries of the earlier 37 abbeys, it is today the oldest surviving Cistercian house in the world.[22]

The Norman invasion of Wales opened the church in Wales to fresh, invigorating streams of continental reform, as well as to the new monastic orders.[23] The Benedictine houses were established in the Normanised fringes and in the shadow of Norman castles, but because they were seen as instruments of conquest, they failed to make any real impression on the local Welsh population.[24] The Cistercians, in contrast, sought out solitude in the mountains and moorlands, and were highly successful. Thirteen Cistercian monasteries, all in remote locations, were founded in Wales between 1131 and 1226. The first of these was Tintern Abbey, which was sited in a remote river valley, and depended largely on its agricultural and pastoral activities for survival.[25] Other abbeys, such as at Neath, Strata Florida, Conwy and Valle Crucis became among the most hallowed names in the history of religion in medieval Wales.[26] Their austere discipline seemed to echo the ideals of the Celtic saints, and the emphasis on pastoral farming fit well into the Welsh stock-rearing economy.[26]

In Yorkshire, Rievaulx Abbey was founded from Clairvaux in 1131, on a small, isolated property donated by Walter Espec, with the support of Thurstan, Archbishop of York. By 1143, three hundred monks had entered Rievaulx, including the famous St Ælred. It was from Rievaulx that a foundation was made at Melrose, which became the earliest Cistercian monastery in Scotland. Located in Roxburghshire, it was built in 1136 by King David I of Scotland, and completed in less than ten years.[27] Another important offshoot of Rievaulx was Revesby Abbey in Lincolnshire.[4]

Fountains Abbey was founded in 1132 by discontented Benedictine monks from St Mary's Abbey, York, who desired a return to the austere Rule of St Benedict. After many struggles and great hardships, St Bernard agreed to send a monk from Clairvaux to instruct them, and in the end they prospered. Already by 1152, Fountains had many offshoots, including Newminster Abbey (1137) and Meaux Abbey (1151).[4]

In the spring of 1140, Saint Malachy, Archbishop of Armagh, visited Clairvaux, becoming a personal friend of St Bernard and an admirer of the Cistercian rule. He left four of his companions to be trained as Cistercians, and returned to Ireland to introduce Cistercian monasticism there.[28] St Bernard viewed the Irish at this time as being in the "depth of barbarism": "... never had he found men so shameful in their morals, so wild in their rites, so impious in their faith, so barbarous in their laws, so stubborn in discipline, so unclean in their life. Christians in name, in fact they were pagans."[29]

Mellifont Abbey was founded in County Louth in 1142 and from it daughter houses of Bective Abbey in County Meath (1147), Inislounaght Abbey in County Tipperary (1147–1148), Baltinglass in County Wicklow (1148), Monasteranenagh in County Limerick (1148), Kilbeggan in County Westmeath (1150) and Boyle Abbey in County Roscommon (1161).[30] Malachy's intensive pastoral activity was highly successful: "Barbarous laws disappeared, Roman laws were introduced: everywhere ecclesiastical customs were received and the contrary rejected... In short all things were so changed that the word of the Lord may be applied to this people: Which before was not my people, now is my people."[31]

As in Wales, there was no significant tradition of Benedictine monasticism in Ireland on which to draw. In the Irish case, this was a disadvantage and represented an insecure foundation for Cistercian expansion. Irish Cistercian monasticism would eventually become isolated from the disciplinary structures of the order, leading to a decline which set in by the 13th century.[32]

Meanwhile, the Cistercian influence in the Church more than kept pace with this material expansion.[3] St Bernard had become mentor to popes and kings, and in 1145, King Louis VII's brother, Henry of France, entered Clairvaux.[33] That same year, Bernard saw one of his monks elected pope as Pope Eugene III.[34] Eugene was an Italian of humble background, who had first been drawn to monasticism at Clairvaux by the magnetism of Bernard. At the time of his election, he was Abbot of Saints Vincenzo and Anastasio outside Rome.[35]

A considerable reinforcement to the Order was the merger of the Savigniac houses with the Cistercians, at the insistence of Eugene III. Thirteen English abbeys, of which the most famous were Furness Abbey and Jervaulx Abbey, thus adopted the Cistercian formula.[4] In Dublin, the two Savigniac houses of Erenagh and St Mary's became Cistercian.[30] It was in the latter case that medieval Dublin acquired a Cistercian monastery in the very unusual suburban location of Oxmantown, with its own private harbour called The Pill.[36]

By 1152, there were 54 Cistercian monasteries in England, few of which had been founded directly from the Continent.[4] Overall, there were 333 Cistercian abbeys in Europe, so many that a halt was put to this expansion.[37] Nearly half of these houses had been founded, directly or indirectly, from Clairvaux, so great was St Bernard's influence and prestige. He later came popularly to be regarded as the founder of the Cistercians, who have often been called Bernardines.[3] Bernard died in 1153, one month after his pupil Eugene III.[38]

Later expansion

From its solid base, the order spread all over western Europe: into Germany, Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Croatia, Italy, Sicily, Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Hungary, Norway, Sweden, Spain and Portugal. One of the most important libraries of the Cistercians was in Salem, Germany.

_2.jpg)

In 1153, the first King of Portugal, D. Afonso Henriques (Afonso, I), founded the Cistercian Alcobaça Monastery. The original church was replaced by the present construction from 1178, although construction progressed slowly due to attacks by the Moors. As with many Cistercian churches, the first parts to be completed was the eastern parts necessary for the priest-monks: the high altar, side altars and choir stalls. The abbey's church was consecrated in 1223. Two further building phases followed in order to complete the nave, leading to the final consecration of the medieval church building in 1252.[39]

As a consequence of the wars between the Christians and Moors on the Iberian Peninsula, the Cistercians established a military branch of the order in Castile in 1157: the Order of Calatrava. Membership of the Cistercian Order had included a large number of men from knightly families, and when King Alfonso VII began looking for a military order to defend the Calatrava, which had been recovered from the Moors a decade before, the Cistercian Abbot Raymond of Fitero offered his help. This apparently came at the suggestion of Diego Valasquez, a monk and former knight who was "well acquainted with military matters", and proposed that the lay brothers of the abbey were to be employed as "soldiers of the Cross" to defend Calatrava. The initial successes of the new order in the Spanish Reconquista were brilliant, and the arrangement was approved by the General Chapter at Cîteaux and successive popes, giving the Knights of Calatrava their definitive rule in 1187. This was modeled upon the Cistercian rule for lay brothers, which included the evangelical counsels of poverty, chastity, and obedience; specific rules of silence; abstinence on four days a week; the recitation of a fixed number of Pater Nosters daily; to sleep in their armour; and to wear, as their full dress, the Cistercian white mantle with the scarlet cross fleurdelisée.[40]

Calatrava was not subject to Cîteaux, but to Fitero's mother-house, the Cistercian Abbey of Morimond in Burgundy. By the end of the 13th century, it had become a major autonomous power within the Castilian state, subject only to Morimond and the Pope; with abundant resources of men and wealth, lands and castles scattered along the borders of Castile, and feudal lordship over thousands of peasants and vassals. On more than one occasion, the Order of Calatrava brought to the field a force of 1200 to 2000 knights – considerable in medieval terms. Over time, as the Reconquista neared completion, the canonical bond between Calatrava and Morimond relaxed more and more, and the knights of the order became virtually secularized, finally undergoing dissolution in the 18th-19th centuries.[40]

The first Cistercian abbey in Bohemia was founded in Sedlec near Kutná Hora in 1142. In the late 13th century and early 14th century, the Cistercian order played an essential role in the politics and diplomacy of the late Přemyslid and early Luxembourg state, as reflected in the Chronicon Aulae Regiae. This chronicle was written by Otto and Peter of Zittau, abbots of the Zbraslav abbey (Latin: Aula Regia, "Royal Hall"), founded in 1292 by the King of Bohemia and Poland, Wenceslas II. The order also played the main role in the early Gothic art of Bohemia; one of the outstanding pieces of Cistercian architecture is the Alt-neu Shul, Prague. The first abbey in the present day Romania was founded on 1179, at Igris (Egres), and the second on 1204, the Cârța Monastery.

Following the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in the 1170s, the English improved the standing of the Cistercian Order in Ireland with nine foundations: Dunbrody Abbey, Inch Abbey, Grey Abbey, Comber Abbey, Duiske Abbey, Abington, Abbeylara and Tracton.[41] This last abbey was founded in 1225 from Whitland Abbey in Wales, and at least in its earliest years, its monks were Welsh-speaking. By this time, another ten abbeys had been founded by Irishmen since the invasion, bringing the total number of Cistercian houses in Ireland to 31. This was almost half the number of those in England, but it was about thrice the number in each of Scotland and Wales.[42] Most of these monasteries enjoyed either noble, episcopal or royal patronage. In 1269, the Archbishop of Cashel joined the order and established a Cistercian house at the foot of the Rock of Cashel in 1272.[43] Similarly, the Irish-establishment of Abbeyknockmoy in County Galway was founded by King of Connacht, Cathal Crobhdearg Ua Conchobair, who died a Cistercian monk and was buried there in 1224.[44]

By the end of the 13th century, the Cistercian houses numbered 500.[45] At the order's height in the 15th century, it would have nearly 750 houses.

It often happened that the number of lay brothers became excessive and out of proportion to the resources of the monasteries, there being sometimes as many as 200, or even 300, in a single abbey. On the other hand, in some countries, the system of lay brothers in course of time worked itself out; thus in England by the close of the 14th century it had shrunk to relatively small proportions, and in the 15th century the regimen of the English Cistercian houses tended to approximate more and more to that of the Black Monks.[3]

Decline and attempted reforms

For a hundred years, until the first quarter of the 13th century, the Cistercians supplanted Cluny as the most powerful order and the chief religious influence in western Europe. But then in turn their influence began to wane,[3] as the initiative passed to the mendicant orders, in Ireland,[32] Wales[26] and elsewhere.

However, some of the reasons of Cistercian decline were internal. Firstly, there was the permanent difficulty of maintaining the initial fervour of a body embracing hundreds of monasteries and thousands of monks, spread all over Europe. The very raison d'être of the Cistercian order consisted of its being a reform, by means of a return to primitive monasticism with its agricultural labour and austere simplicity. Therefore, any failures to live up to the proposed ideal was more detrimental among Cistercians than among Benedictines, who were intended to live a life of self-denial but not of particular austerity.[3]

Relaxations were gradually introduced into Cistercian life with regard to diet and to simplicity of life, and also in regard to the sources of income, rents and tolls being admitted and benefices incorporated, as was done among the Benedictines. The farming operations tended to produce a commercial spirit; wealth and splendour invaded many of the monasteries, and the choir monks abandoned manual labour. The later history of the Cistercians is largely one of attempted revivals and reforms. For a long time, the General Chapter continued to battle bravely against the invasion of relaxations and abuses.[3]

In Ireland, the information on the Cistercian Order after the Anglo-Norman invasion gives a rather gloomy impression.[46] Absenteeism among Irish abbots at the General Chapter became a persistent and much criticised problem in the 13th century, and escalated into the conspiratio Mellifontis, a "rebellion" by the abbeys of the Mellifont filiation. Visitors were appointed to reform Mellifont on account of the multa enormia that had arisen there, but in 1217 the abbot refused their admission and had lay brothers bar the abbey gates. There was also trouble at Jerpoint, and alarmingly, the abbots of Baltinglass, Killenny, Kilbeggan and Bective supported the actions of the "revolt".[47]

In 1228, the General Chapter sent the Abbot of Stanley in Wiltshire, Stephen of Lexington, on a well-documented visitation to reform the Irish houses.[48] A graduate of both Oxford and Paris, and a future Abbot of Clairvaux (to be appointed in 1243), Stephen was one of the outstanding figures in 13th-century Cistercian history. He found his life threatened, his representatives attacked and his party harassed, while the three key houses of Mellifont, Suir and Maigue had been fortified by their monks to hold out against him.[49] However, with the help of his assistants, the core of obedient Irish monks and the aid of both English and Irish secular powers, he was able to envisage the reconstruction of the Cistercian province in Ireland.[50] Stephen dissolved the Mellifont filiation altogether, and subjected 15 monasteries to houses outside Ireland.[46] In breadth and depth, his instructions constituted a radical reform programme: "They were intended to put an end to abuses, restore the full observance of the Cistercian way of life, safeguard monastic properties, initiate a regime of benign paternalism to train a new generation of religious, isolate trouble-makers and institute an effective visitation system."[51] The arrangement lasted almost half a century, and in 1274, the filiation of Mellifont was reconstituted.[52]

In Germany the Cistercians were instrumental in the spread of Christianity east of the Elbe. They developed grants of territories of 180,000 acres where they would drain land, build monasteries and plan villages. Many towns near Berlin owe their origins to this order, including Heiligengrabe and Chorin; its Chorin Abbey was the first brick-built monastery in the area.[53] By this time, however, "the Cistercian order as a whole had experienced a gradual decline and its central organisation was noticeably weakened."[52]

In 1335, the French cardinal Jacques Fournier, a former Cistercian monk and the son of a miller, was elected and consecrated Pope Benedict XII. The maxim attributed to him, "the pope must be like Melchizedech who had no father, no mother, nor even a family tree", is revealing of his character. Benedict was shy of personal power and was devoted exclusively to restoring the authority of the Church.[54] As a Cistercian, he had a notable theological background and, unlike his predecessor John XXII, he was a stranger to nepotism and scrupulous with his appointments.[55] He promulgated a series of regulations to restore the primitive spirit of the Cistercian Order.[3]

By the 15th century, however, of all the orders in Ireland, the Cistercians had most comprehensively fallen on evil days. The General Chapter lost virtually all its power to enforce its will in Ireland, and the strength of the order which derived from this uniformity declined. In 1496, there were efforts to establish a strong national congregation to assume this role in Ireland, but monks of the English and Irish "nations" found themselves unable to cooperate for the good of the order. The General Chapter appointed special reformatores, but their efforts proved fruitless. One such reformer, Abbot John Troy of Mellifont, despaired of finding any solution to the ruin of the order.[56] According to his detailed report to the General Chapter, the monks of only two monasteries, Dublin and Mellifont, kept the rule or even wore the habit.[57] He identified the causes of this decline as the ceaseless wars and hatred between the two nations; a lack of leadership; and the control of many of the monasteries by secular dynasties who appointed their own relatives to positions.[58]

In the 15th century, various popes endeavoured to promote reforms. All these efforts at a reform of the great body of the order proved unavailing; but local reforms, producing various semi-independent offshoots and congregations, were successfully carried out in many parts in the course of the 15th and 16th centuries.[3]

Protestant Reformation

During the English Reformation, Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries saw the confiscation of church land throughout the country, which was disastrous for the Cistercians in England. Laskill, an outstation of Rievaulx Abbey and the only medieval blast furnace so far identified in Great Britain, was one of the most efficient blast furnaces of its time.[59] Slag from contemporary furnaces contained a substantial concentration of iron, whereas the slag of Laskill was low in iron content, and is believed to have produced cast iron with efficiency similar to a modern blast furnace.[60] The monks may have been on the verge of building dedicated furnaces for the production of cast iron,[61] but the furnace did not survive Henry's Dissolution in the late 1530s, and the type of blast furnace pioneered there did not spread outside Rievaulx.[62] Some historians believe that the suppression of the English monasteries may have stamped out an industrial revolution.[61]

After the Protestant Reformation

In the 16th century had arisen the reformed Congregation of the Feuillants, which spread widely in France and Italy, in the latter country under the name of Improved Bernardines. The French congregation of Sept-Fontaines (1654) also deserves mention. In 1663 de Rancé reformed La Trappe (see Trappists).[3]

In the 17th century another great effort at a general reform was made, promoted by the pope and the king of France; the general chapter elected Richelieu (commendatory) abbot of Cîteaux, thinking he would protect them from the threatened reform. In this they were disappointed, for he threw himself wholly on the side of reform. So great, however, was the resistance, and so serious the disturbances that ensued, that the attempt to reform Cîteaux itself and the general body of the houses had again to be abandoned, and only local projects of reform could be carried out.[3]

The Protestant Reformation, the ecclesiastical policy of Joseph II, the French Revolution, and the revolutions of the 18th century almost wholly destroyed the Cistercians. But some survived, and since the beginning of the last half of the 19th century there has been a considerable recovery.[3]

In 1892, the Trappists left the Cistercians and founded a new order, named the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance.[63] The Cistercians that remained within the original order thus came to be known as the "Common Observance".

Influence

Architecture

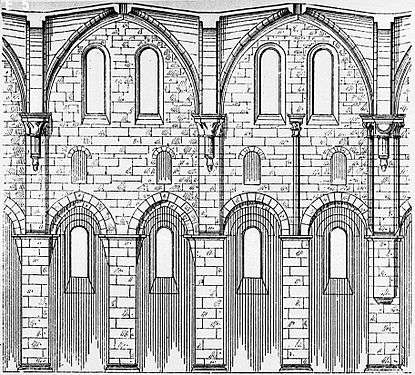

Cistercian architecture has made an important contribution to European civilisation. Architecturally speaking, the Cistercian monasteries and churches, owing to their pure style, may be counted among the most beautiful relics of the Middle Ages.[4] Cistercian foundations were primarily constructed in Romanesque and Gothic architecture during the Middle Ages; although later abbeys were also constructed in Renaissance and Baroque.

Theological principles

In the mid-12th century, one of the leading churchmen of his day, the Benedictine Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, united elements of Norman architecture with elements of Burgundinian architecture (rib vaults and pointed arches respectively), creating the new style of Gothic architecture.[64] This new "architecture of light" was intended to raise the observer "from the material to the immaterial"[65] – it was, according to the 20th-century French historian Georges Duby, a "monument of applied theology".[66] Although St Bernard saw much of church decoration as a distraction from piety, and the builders of the Cistercian monasteries had to adopt a style that observed the numerous rules inspired by his austere aesthetics, the order itself was receptive to the technical improvements of Gothic principles of construction and played an important role in its spread across Europe.[67]

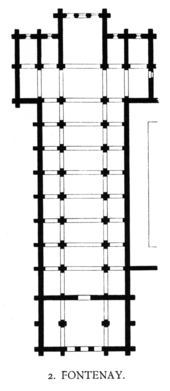

This new Cistercian architecture embodied the ideals of the order, and was in theory at least utilitarian and without superfluous ornament.[68] The same "rational, integrated scheme" was used across Europe to meet the largely homogeneous needs of the order.[68] Various buildings, including the chapter-house to the east and the dormitories above, were grouped around a cloister, and were sometimes linked to the transept of the church itself by a night stair.[68] Usually Cistercian churches were cruciform, with a short presbytery to meet the liturgical needs of the brethren, small chapels in the transepts for private prayer, and an aisled nave that was divided roughly in the middle by a screen to separate the monks from the lay brothers.[69]

Engineering and construction

The building projects of the Church in the High Middle Ages showed an ambition for the colossal, with vast amounts of stone being quarried, and the same was true of the Cistercian projects.[70] Foigny Abbey was 98 metres (322 ft) long, and Vaucelles Abbey was 132 metres (433 ft) long.[70] Monastic buildings came to be constructed entirely of stone, right down to the most humble of buildings. In the 12th and 13th centuries, Cistercian barns consisted of a stone exterior, divided into nave and aisles either by wooden posts or by stone piers.[71]

The Cistercians acquired a reputation in the difficult task of administering the building sites for abbeys and cathedrals.[72] St Bernard's own brother, Achard, is known to have supervised the construction of many abbeys, such as Himmerod Abbey in the Rhineland.[72] Others were Raoul at Saint-Jouin-de-Marnes, who later became abbot there; Geoffrey d'Aignay, sent to Fountains Abbey in 1133; and Robert, sent to Mellifont Abbey in 1142.[72] On one occasion the Abbot of La Trinité at Vendôme loaned a monk named John to the Bishop of Le Mans, Hildebert de Lavardin, for the building of a cathedral; after the project was completed, John refused to return to his monastery.[72]

The Cistercians "made it a point of honour to recruit the best stonecutters", and as early as 1133, St Bernard was hiring workers to help the monks erect new buildings at Clairvaux.[73] It is from the 12th century Byland Abbey in Yorkshire that the oldest recorded example of architectural tracing is found.[74] Tracings were architectural drawings incised and painted in stone, to a depth of 2–3 mm, showing architectural detail to scale.[74] The first tracing in Byland illustrates a west rose window, while the second depicts the central part of that same window.[74] Later, an illustration from the latter half of the 16th century would show monks working alongside other craftsmen in the construction of Schönau Abbey.[73]

Legacy

The Cistercian abbeys of Fontenay in France,[75] Fountains in England,[76] Alcobaça in Portugal,[77] Poblet in Spain[78] and Maulbronn in Germany are today recognised as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[79]

The abbeys of France and England are fine examples of Romanesque and Gothic architecture. The architecture of Fontenay has been described as "an excellent illustration of the ideal of self-sufficiency" practised by the earliest Cistercian communities.[75] The abbeys of 12th century England were stark and undecorated – a dramatic contrast with the elaborate churches of the wealthier Benedictine houses – yet to quote Warren Hollister, "even now the simple beauty of Cistercian ruins such as Fountains and Rievaulx, set in the wilderness of Yorkshire, is deeply moving".[13]

In the purity of architectural style, the beauty of materials and the care with which the Alcobaça Monastery was built,[77] Portugal possesses one of the most outstanding and best preserved examples of Early Gothic.[80] Poblet Monastery, one of the largest in Spain, is considered similarly impressive for its austerity, majesty, and the fortified royal residence within.[78]

The fortified Maulbronn Abbey in Germany is considered "the most complete and best-preserved medieval monastic complex north of the Alps".[79] The Transitional Gothic style of its church had a major influence in the spread of Gothic architecture over much of northern and central Europe, and the abbey's elaborate network of drains, irrigation canals and reservoirs has since been recognised as having "exceptional" cultural interest.[79]

In Poland, the former Cistercian monastery of Pelplin Cathedral is an important example of Brick Gothic. Wąchock Abbey is one of the most valuable examples of Polish Romanesque architecture. The largest Cistercian complex, the Abbatia Lubensis (Lubiąż, Poland), is a masterpiece of baroque architecture and the second largest Christian architectural complex in the world.

Art

The mother house of the order, Cîteaux, had developed the most advanced style of painting in France, at least in illuminated manuscripts, during the first decades of the 12th century, playing an important part in the development of the image of the Tree of Jesse. However, as Bernard of Clairvaux, who had a personal violent hostility to imagery, increased in influence in the order, painting and decoration gradually diminished in Cistercian manuscripts, and they were finally banned altogether in the order, probably from the revised rules approved in 1154. Any wall paintings that may have existed were presumably destroyed. Crucifixes were allowed, and later some painting and decoration crept back in.[81] Bernard's outburst in a letter against the fantastical decorative motifs in Romanesque art is famous:

...But these are small things; I will pass on to matters greater in themselves, yet seeming smaller because they are more usual. I say naught of the vast height of your churches, their immoderate length, their superfluous breadth, the costly polishings, the curious carvings and paintings which attract the worshipper's gaze and hinder his attention.... But in the cloister, under the eyes of the Brethern who read there, what profit is there in those ridiculous monsters, in the marvellous and deformed comeliness, that comely deformity? To what purpose are those unclean apes, those fierce lions, those monstrous centaurs, those half-men, those striped tigers, those fighting knights, those hunters winding their horns? Many bodies are there seen under one head, or again, many heads to a single body. Here is a four-footed beast with a serpent's tail; there, a fish with a beast's head. Here again the forepart of a horse trails half a goat behind it, or a horned beast bears the hinder quarters of a horse. In short, so many and so marvellous are the varieties of divers shapes on every hand, that we are more tempted to read in the marble than in our books, and to spend the whole day in wondering at these things rather than in meditating the law of God. For God's sake, if men are not ashamed of these follies, why at least do they not shrink from the expense?

— [82]

Some Cistercian abbeys did contain later medieval wall paintings, two examples being found in Ireland: Archaeological evidence indicates the presence of murals in Tintern Abbey, and traces still survive in the presbytery of Abbeyknockmoy.[83] The murals in Abbeyknockmoy depict Saint Sebastian, the Crucifixion, the Trinity and the three living and three dead,[68] and the abbey also contains a fine example of a sculptured royal head on a capital in the nave, with carefully defined eyes, an elaborate crown and long curly hair.[44] The east end of Corcomroe Abbey in County Clare is similarly distinguished by high-quality carvings, several of which "demonstrate precociously naturalistic renderings of plants".[84] By the Baroque period, decoration could be very elaborate, as at Alcobaça in Portugal, which has carved and gilded retables and walls of azulejo tiles.

Furthermore, many Cistercian abbey churches housed the tombs of royal or noble patrons, and these were often as elaborately carved and painted as in other churches. Notable dynastic burial places were Alcobaça for the Kings of Portugal, Cîteaux for the Dukes of Burgundy, and Poblet for the Kings of Aragon. Corcomroe in Ireland contains one of only two surviving examples of Gaelic royal effigies from 13th and 14th century Ireland: the sarcophagal tomb of Conchobar na Siudaine Ua Briain (d. 1268).[85]

Commercial enterprise and technological diffusion

According to one modern Cistercian, "enterprise and entrepreneurial spirit" have always been a part of the order's identity, and the Cistercians "were catalysts for development of a market economy" in 12th-century Europe.[86] It was as agriculturists and horse and cattle breeders that the Cistercians exercised their chief influence on the progress of civilisation in the Middle Ages. As the great farmers of those days, many of the improvements in the various farming operations were introduced and propagated by them, and this is where the importance of their extension in northern Europe is to be estimated. They developed an organised system for selling their farm produce, cattle and horses, and notably contributed to the commercial progress of the countries of western Europe.[3] To the wool and cloth trade, which was especially fostered by the Cistercians, England was largely indebted for the beginnings of her commercial prosperity.[4]

Farming operations on so extensive a scale could not be carried out by the monks alone, whose choir and religious duties took up a considerable portion of their time; and so from the beginning the system of lay brothers was introduced on a large scale. The duties of the lay brothers, recruited from the peasantry, consisted in carrying out the various fieldworks and plying all sorts of useful trades. They formed a body of men who lived alongside of the choir monks, but separate from them, not taking part in the canonical office, but having their own fixed round of prayer and religious exercises. They were never ordained, and never held any office of superiority. It was by this system of lay brothers that the Cistercians were able to play their distinctive part in the progress of European civilisation.[3]

Until the Industrial Revolution, most of the technological advances in Europe were made in the monasteries.[86] According to the medievalist Jean Gimpel, their high level of industrial technology facilitated the diffusion of new techniques: "Every monastery had a model factory, often as large as the church and only several feet away, and waterpower drove the machinery of the various industries located on its floor."[87] Waterpower was used for crushing wheat, sieving flour, fulling cloth and tanning – a "level of technological achievement [that] could have been observed in practically all" of the Cistercian monasteries.[88] The English science historian James Burke examines the impact of Cistercian waterpower, derived from Roman watermill technology such as that of Barbegal aqueduct and mill near Arles in the fourth of his ten-series Connections (TV series), called "Faith in Numbers."

The Cistercian order was innovative in developing techniques of hydraulic engineering for monasteries established in remote valleys.[67] In Spain, one of the earliest surviving Cistercian houses, the Real Monasterio de Nuestra Senora de Rueda in Aragon, is a good example of such early hydraulic engineering, using a large waterwheel for power and an elaborate water circulation system for central heating.

The Cistercians are known to have been skilled metallurgists, and knowledge of their technological advances was transmitted by the order.[89] Iron ore deposits were often donated to the monks along with forges to extract the iron, and within time surpluses were being offered for sale. The Cistercians became the leading iron producers in Champagne, from the mid-13th century to the 17th century, also using the phosphate-rich slag from their furnaces as an agricultural fertiliser.[90] As the historian Alain Erlande-Brandenburg writes:

The quality of Cistercian architecture from the 1120s onwards is related directly to the Order's technological inventiveness. They placed importance on metal, both the extraction of the ore and its subsequent processing. At the abbey of Fontenay the forge is not outside, as one might expect, but inside the monastic enclosure: metalworking was thus part of the activity of the monks and not of the lay brothers. This spirit accounted for the progress that appeared in spheres other than building, and particularly in agriculture. It is probable that this experiment spread rapidly; Gothic architecture cannot be understood otherwise.

— [91]

Theology

By far the most influential of the early Cistercians was Bernard of Clairvaux. According to the historian Piers Paul Read, his vocation to the order, by deciding "to choose the narrowest gate and steepest path to the Kingdom of Heaven at Citeaux demonstrates the purity of his vocation".[92] His piety and asceticism "qualified him to act as the conscience of Christendom, constantly chastising the rich and powerful and championing the pure and weak."[33] He rebuked the moderate and conciliatory Abbot Peter the Venerable for the pleasant life of the Benedictine monks of Cluny.[92] Besides his piety, Bernard was an outstanding intellectual, which he demonstrated in his sermons on Grace, Free will and the Song of Songs.[33] He perceived the attraction of evil not simply as lying in the obvious lure of wealth and worldly power, but in the "subtler and ultimately more pernicious attraction of false ideas".[33] He was quick to recognise heretical ideas, and in 1141 and 1145 respectively, he accused the celebrated scholastic theologian Peter Abelard and the popular preacher Henry of Lausanne of heresy.[33] He was also charged with the task of promulgating Pope Eugene's bull, Quantum praedecessores, and his eloquence in preaching the Second Crusade had the desired effect: when he finished his sermon, so many men were ready to take the Cross that Bernard had to cut his habit into strips of cloth.[93]

Although Bernard's De laude novae militiae was in favour of the Knights Templar, a Cistercian was also one of the few scholars of the Middle Ages to question the existence of the military orders during the Crusades.[94] The English Cistercian Abbot Isaac of l'Etoile, near Poitiers, preached against the "new monstrosity" of the nova militia in the mid-12th century and denounced the use of force to convert members of Islam.[94] He also rejected the notion that crusaders could be regarded as martyrs if they died while despoiling non-Christians.[94] Nevertheless, the Bernardine concept of Catholic warrior asceticism predominated in Christendom and exerted multiple influences culturally and otherwise, notably forming the metaphysical background of the otherworldly, pure-hearted Arthurian knight Sir Galahad, Cistercian spirituality permeating and underlying the medieval "anti-romance" and climactic sublimation of the Grail Quest, the Queste del Saint Graal—indeed, direct Cistercian authorship of the work is academically considered highly probable. Cistercian-Bernardine chivalrous mysticism is especially exhibited in how the celibate, sacred warrior Galahad, due to interior purity of the heart (cardiognosis in Desert Father terminology), is alone in being granted the beatific vision of the eucharistic Holy Grail.[95]

City growth

A 2016 study suggested that "English counties that were more exposed to Cistercian monasteries experienced faster productivity growth from the 13th century onwards" and that this influence lasts beyond the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s.[96] It has been maintained that this was because the Order’s lifestyle and supposed pursuit of wealth were early manifestations of the Protestant work ethic, which has also been associated with city growth.[97][98]

Present day

Abbots General

Before the French Revolution the Abbot of Citeaux was automatically supreme head of the order. The first abbot was Robert de Molesme and others included Gilbert le Grand and Souchier. Later the order was made subject to commendatory abbots, non-monks, who included Cardinal Giovanni Maria Gabrielli, O. Cist., Richelieu.[99]

- 63. 1814-1820: Raimondo Giovannini

- 64. 1820-1825: Sisto Benigni

- 65. 1825-1826: Giuseppe Fontana

- 66. 1826-1830: Vescelaso Vasini

- 67. 1830-1845: Sixtus Benigni

- 68. 1845-1850: Livio Fabretti

- 69. 1850-1853: Tomaso Mossi

- 70. 1853-1856: Angelo Geniani

- 71. 1856-1880: Theobald Cesari

- 72. 1880–1890: Gregorio Bartolini

- 73. 1891–1900: Leopold Wackarž, (Hohenfurth Abbey)

- 74. 1900–1920: Amadeus de Bie, (Bornem Abbey)

- 75. 1920–1927: Cassian Haid, (Territorial Abbey of Wettingen-Mehrerau)

- 76. 1927-1936: Franciscus Janssens, (Achel Abbey)

- 77. 1936-1950: Edmondus Bernardini, (Santa Croce Abbey)

- 78. 1950-1953: Mattheus Quatember

- 79. 1953-1985: Sighard Kleiner

- 80. 1985-1995: Ferenc Polikárp Zakar, (Zirc Abbey)

- 81. 1995-2010: Maurus Esteva Alsina, (Royal Abbey of Santa Maria de Poblet)

- 82. 2010-current: Mauro-Giuseppe Lepori, (Hauterive Abbey)

Monastic life

At the time of monastic profession, five or six years after entering the monastery, candidates promise "conversion" – fidelity to monastic life, which includes an atmosphere of silence.[100] Cistercian monks and nuns have a reputation of being silent, which has led to the public idea that they take a vow of silence.[100] This has actually never been the case, although silence is an implicit part of an outlook shared by Cistercian and Benedictine monasteries.[100] In a Cistercian monastery, there are three reasons for speaking:

functional communication at work or in community discussion, spiritual exchange with one’s superiors or spiritual adviser on different aspects of one’s personal life, and spontaneous conversation on special occasions. These forms of communication are integrated into the discipline of maintaining a general atmosphere of silence, which is an important help to continual prayer.[100]

Many Cistercian monasteries make produce goods such as cheese, bread and other foodstuffs. In the United States, many Cistercian monasteries support themselves through agriculture, forestry and rental of farmland. The Cistercian Abbey of Our Lady of Spring Bank, in Sparta, Wisconsin, from 2001 to 2011 supported itself with a group called "Laser Monks", which provided laser toner and ink jet cartridges, as well as items such as gourmet coffees and all-natural dog treats.[86][101]

Additionally, the Cistercian monks of Our Lady of Dallas monastery run the Cistercian Preparatory School, a Catholic school for boys in Irving, Texas.

Cistercian nuns

There are a large number of Cistercian nuns; the first community was founded in the Diocese of Langres in 1125; at the period of their widest extension there are said to have been 900 monasteries, and the communities were very large.[3] In addition to being devoted to contemplation, the nuns in earlier times of the Order did agricultural work in the fields. In Spain and France a number of Cistercian abbesses had extraordinary privileges.[102][3] Numerous reforms took place among the nuns.[3] One of the best known of Cistercian women's communities was probably the Abbey of Port-Royal, reformed by Mother Marie Angélique Arnauld, and associated with the Jansenist controversy.

The nuns have also followed the division into different orders as seen among the monks. Those who follow the Trappist reforms of De Rancé are called Trappistines.

Non-Catholic Cistercians

Since 2010 there is also a branch of Anglican Cistercians in England, and in Wales since 2017.[103] This is a dispersed and uncloistered order of single, celibate, and married men officially recognized by the Church of England. The Order enjoys an ecumenical link with the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance.

There are also Cistercians of the Lutheran church residing in Amelungsborn Abbey and Loccum Abbey.

See also

Notes

- Oxford English Dictionary (1989).

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 3rd ed., 1992.

-

- Herbert Thurston. "Cistercians in the British Isles". Catholic Encyclopedia. NewAdvent.org. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- OCist.Hu - A Ciszterci Rend Zirci Apátsága (31 December 2002). "History". OCist.Hu. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- Read, p 94

- Tobin, pp 29, 33, 36.

- Read, pp 94–95

- Gildas, Marie. "Cistercians." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 21 January 2020

- Tobin, pp 37–38.

- Hollister, p 209

- Hollister, p 209–10

- Hollister, p 210

- "Latin text". Users.skynet.be. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- Migne, Patrol. Lat. clxvi. 1377

- Watt, p 52

- See F. A. Gasquet, Sketch of Monastic Constitutional History, pp. xxxv-xxxviii, prefixed to English trans. Of Montalembert's Monks of the West, ed. 1895

- Gately, Iain (2009). Drink: A Cultural History of Alcohol. New York: Gotham Books. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-592-40464-3.

- Tobin, pp 46

- Read, p 93, 95

- Read, p. 95

- Rein, Zisterzienserstift. "Welt-ältestes Zisterzienserkloster Stift Rein seit 1129". www.stift-rein.at.

- Roderick, p 162–163

- Roderick, p 163

- Dykes, pp 76–78

- Roderick, p 164

- Michael Barrett (1 October 1911). "Abbey of Melrose". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- Watt, p. 20

- Watt, p 17

- Watt, p 21

- Watt, pp 17–18

- Lalor, p 200

- Read, p 118

- Read, pp 117–118

- Read, p. 117

- Clarke, pp 42-43

- Logan, p 139

- Read, p 126

- Toman, p 98

- Charles Moeller (1 November 1908). "Military Order of Calatrava". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- Watt, pp 49–50

- Watt, p 50

- Watt, p 115

- Doran, p 53

- "Cistercian Order of the Strict Observance (Trappists): Frequently Asked Questions". Ocso.org. 8 December 2003. Archived from the original on 17 September 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- Richter, p 154

- Watt, p 53

- Watt, p 55

- Watt, p 56

- Watt, pp 56–57

- Watt, p 59

- Richter, p 155

- Richie, p21

- Rendina, p 376

- Rendina, p 375

- Watt, p 187

- Watt, pp 187–188

- Watt, p 188

- Woods, p 37

- R. W. Vernon, G. McDonnell and A. Schmidt, 'An integrated geophysical and analytical appraisal of early iron-working: three case studies' Historical Metallurgy 31(2) (1998), 72–5 79

- David Derbyshire, 'Henry "Stamped Out Industrial Revolution"', The Daily Telegraph (21 June 2002); cited by Woods, p 37.

- An agreement (immediately after that) concerning the 'smythes' with the Earl of Rutland in 1541 refers to blooms. H. R. Schubert, History of the British iron and steel industry from c. 450 BC to AD 1775 (Routledge, London 1957), 395–7.

- Alcuin Schachenmayr and Polycarp Zakar: Union And Division: The Proceedings of the Three Trappist Congregations at their General Chapter in 1892. In: Analecta Cisterciensia 56 (2006) 334–384.

- Toman, pp 8–9

- Toman, p 9

- Toman, p 14

- Toman, p 10

- Lalor, p 1

- Lalor, p 1, 38

- Erlande-Brandenburg, p 32–34

- Erlande-Brandenburg, p 28

- Erlande-Brandenburg, p 50

- Erlande-Brandenburg, p 101

- Erlande-Brandenburg, p 78

- "Cistercian Abbey of Fontenay (No. 165)". UNESCO World Heritage Sites list. unesco.org. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- "Studley Royal Park including the Ruins of Fountains Abbey (No. 372)". UNESCO World Heritage Sites list. unesco.org. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- "Monastery of Alcobaça (No. 505)". UNESCO World Heritage Sites list. unesco.org. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- "Poblet Monastery (No. 518)". UNESCO World Heritage Sites list. unesco.org. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- "Maulbronn Monastery Complex (No. 546)". UNESCO World Heritage Sites list. unesco.org. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Toman, p 289

- Dodwell, 211–214

- "Bernard's letter". Employees.oneonta.edu. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- Lalor, p 1, 716, 1050

- Lalor, p 236

- Doran, p 48

- Rob Baedeker (24 March 2008). "Good Works: Monks build multimillion-dollar business and give the money away". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Gimpel, p 67. Cited by Woods.

- Woods, p 33

- Woods, pp 34–35

- Gimpel, p 68; cited by Woods, p 35

- Erlande-Brandenburg, pp 116–117

- Read, p 96

- Read, p 119

- Read, p 180

- Pauline Matarasso, The Redemption of Chivalry, Geneva, 1979

- Andersen, Thomas Barnebeck; Bentzen, Jeanet; Dalgaard, Carl-Johan; Sharp, Paul (1 March 2016). "Pre-Reformation Roots of the Protestant Ethic" (PDF). The Economic Journal. 127 (604): 1756–1793. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12367. ISSN 1468-0297.

- Nunziata, Luca; Rocco, Lorenzo (1 January 2014). "The Protestant Ethic and Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Religious Minorities from the Former Holy Roman Empire". University Library of Munich, Germany. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Nunziata, Luca; Rocco, Lorenzo (20 January 2016). "A tale of minorities: evidence on religious ethics and entrepreneurship". Journal of Economic Growth. 21 (2): 189–224. doi:10.1007/s10887-015-9123-2. ISSN 1381-4338.

- Die Templer - Ein Einblick und Überblick Door Dr Meinolf Rode

- "Cistercian Order of the Strict Observance (Trappists): Frequently Asked Questions". Ocso.org. 8 December 2003. Archived from the original on 17 September 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- "Our Business Philosophy". The Cistercian Abbey of Our Lady of Spring Bank. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Ghislain Baury, "Emules puis sujettes de l'ordre cistercien. Les cisterciennes de Castille et d'ailleurs face au Chapitre Général aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles", Cîteaux: Commentarii cistercienses, t. 52, fasc. 1–2, 2001, p. 27–60. Ghislain Baury, Les religieuses de Castille. Patronage aristocratique et ordre cistercien, XIIe-XIIIe siècles, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2012.

- "ANGLICAN ORDER OF CISTERCIANS". ANGLICAN ORDER OF CISTERCIANS.

References

- "Art and Architecture: Cistercian," The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages, 4 v. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2010) v.1, p. 157-158.

- Bruun, Mette Birkedal, ed. (2013). The Cambridge Companion to the Cistercian Order. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-17184-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Baury, Ghislain, "Emules puis sujettes de l'ordre cistercien. Les cisterciennes de Castille et d'ailleurs face au Chapitre Général aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles", Cîteaux: Commentarii cistercienses, t. 52, fasc. 1–2, 2001, p. 27–60.

- Baury, Ghislain, Les religieuses de Castille. Patronage aristocratique et ordre cistercien, XIIe-XIIIe siècles, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2012.

- Cawley, Martinus (1988). A Folk Geography of Cistercian U.S.A. Guadalupe Translations.

- Clarke, Howard B.; Dent, Sarah; Johnson, Ruth (2002). Dublinia: The Story of Medieval Dublin. Dublin: O'Brien. ISBN 978-0-86278-785-1.

- Dodwell, C.R.; The Pictorial arts of the West, 800–1200, 1993, Yale UP, ISBN 0-300-06493-4

- Doran, Linda; Lyttleton, James, eds. (2008). Lordship in Medieval Ireland: Image and reality (Hardback, illustrated ed.). Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-041-0.

- Dykes, D.W. (1980). Alan Sorrell: Early Wales Re-created. National Museum of Wales. ISBN 978-0-7200-0228-7.

- Erlande-Brandenburg, Alain (1995). The Cathedral Builders of the Middle Ages. ‘New Horizons’ series. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-30052-7.

- Gimpel, Jean, The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages (New York, Penguin, 1976)

- Hollister, C. Warren (1966). The Making of England, 55 BC to 1399. Volume I of A History of England, edited by Lacey Baldwin Smith (Sixth Edition, 1992 ed.). Lexington, MA. ISBN 978-0-669-24457-1.

- Lalor, Brian, ed. (2003). The Encyclopedia of Ireland. Gill and Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-3000-9.

- Logan, F. Donald, A History of the Church in the Middle Ages.

- Rendina, Claudio (2002). The Popes: Histories and Secrets. translated by Paul McCusker. Seven Locks Press. ISBN 978-1-931643-13-9.

- Richie, Alexandra, "Faust's Metropolis - A History of Berlin" (Harper and Collins 1998)

- Richter, Michael (2005). Medieval Ireland: the enduring tradition (Revised, illustrated ed.). Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-3293-5.

- Rudolph, Conrad, "The 'Principal Founders' and the Early Artistic Legislation of Cîteaux," Studies in Cistercian Art and Architecture 3, Cistercian Studies Series 89 (1987) 1-45

- Rudolph, Conrad, The "Things of Greater Importance": Bernard of Clairvaux's Apologia and the Medieval Attitude Toward Art (1990)

- Rudolph, Conrad, Violence and Daily Life: Reading, Art, and Polemics in the Cîteaux Moralia in Job (1997)

- Tobin, Stephen. The Cistercians: Monks and Monasteries in Europe. The Herbert Press, LTD 1995. ISBN 1-871569-80-X.

- Toman, Rolf, ed. (2007). The Art of Gothic: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting. photography by Achim Bednorz. Tandem Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8331-4676-3.

- Watt, John, The Church in Medieval Ireland. University College Dublin Press; Second Revised Edition (May 1998). ISBN 1-900621-10-X. ISBN 978-1-900621-10-6.

- Woods, Thomas, How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization (2005), ISBN 0-89526-038-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cistercian Order. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |