The Rescue (statue)

The Rescue (1837–1850) is a large marble sculpture group which was assembled in front of the east façade of the United States Capitol building and exhibited there from 1853 until 1958, when it was removed and never restored. The sculptural ensemble was created by sculptor Horatio Greenough (1805–1852) who had previously been commissioned by the U.S. government to create a massive sculpture, George Washington (1832–1841) for the Capitol rotunda, also now removed from that site. Due to long-standing controversies, these two sculptures have diminished Greenough's reputation.

| The Rescue | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Horatio Greenough |

| Year | 1837–1850 |

| Type | White marble |

| Dimensions | 358 cm (141 in) |

| Location | Formerly, East Facade, U.S. Capitol (In storage), Washington, DC |

Description

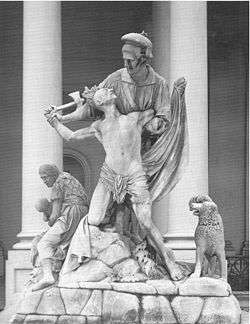

The Rescue was displayed to the right of the large staircase of the east façade of the U.S. Capitol and was a companion piece to another sculpture, Luigi Persico's Discovery of America (1837–1850) — depicting a triumphant Christopher Columbus and a cowering Indian maiden — on the left. The Rescue depicts a confrontation between a bellicose American Indian warrior and a pioneer family. At the left rear of the group, a crouching pioneer woman desperately clasps a small child. To the front, an outsized frontiersman forcibly prevents a tomahawk-wielding Indian from brutally murdering his family. The heroic rescuer, however, refrains from injuring his adversary and displays a total mastery of the situation as well as a certain compassion for his enemy. The vengeful Indian warrior is rendered impotent and childlike. (His posture is loosely based on the central figure of the ancient Laocoön sculpture group.[1]) The frontiersman's helmet-like headgear is fashioned like a Renaissance cap. To the right, the family dog looks on.

History and meaning

Greenough wrote that The Rescue was meant to "commemorate the dangers & difficulty of peopling our continent, and which shall also serve as a memorial of the Indian race", but also "to convey the idea of the triumph of the whites over the savage tribes" .[2] The group has also been seen as rationalizing Andrew Jackson's "Indian Removal" policy of the 1830s.[3] Although Greenough did not name the rescuer, the public recognized him as Daniel Boone and the statuary was widely known as "Daniel Boone Protects His Family."[4]

In 1939, a joint resolution submitted to—but not passed by—the U.S. House of Representatives recommended that The Rescue be "...ground into dust, and scattered to the four winds, that no more remembrance may be perpetuated of our barbaric past, and that it may not be a constant reminder to our American Indian citizens…"[5] Several other protests, including by American Indian groups, were made in the intervening years and in 1958, both Discovery and Rescue were removed from the east façade in preparation for the building's extension. They were placed in storage and—without public discussion—never restored.[6]

Fate

In 1976, a crane accidentally dropped The Rescue while moving it to a new Smithsonian storage area in Maryland, thus reducing it to several fragments. Today they lie next to Discovery, also said to be in poor condition.[7]

In a collaboration between the Middlebury College Museum of Art and the Office of the Architect of the Capitol, the pioneer's dog from The Rescue was exhibited during a temporary show, "Horatio Greenough: An American Sculptor's Drawings" in late 1999.

References

- Fryd, Vivien Green (1987), “Two Sculptures for the Capitol: Horatio Greenough's ‘Rescue’ and Luigi Persico's ‘Discovery of America’” American Art Journal, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Spring, 1987), pp 99–100.

- Boime, Albert (2004), A Social History of Modern Art, Volume 2: Art in an Age of Counterrevolution, 1815-1848, (Series: Social History of Modern Art); University of Chicago Press, pg 527.

- Boime, Op. cit.

- Fryd, Op. cit.

- United States Congress, House, 76th Congress, 1st session, April 26, 1939, House Joint Resolution 276.

- Fryd, Op. cit., pg 93.

- Fryd, Op. cit., pg 96.

External links