Australian Aboriginal languages

The Australian Aboriginal languages consist of around 290–363[1] languages belonging to an estimated 28 language families and isolates, spoken by Aboriginal Australians of mainland Australia and a few nearby islands.[2] The relationships between these languages are not clear at present. Despite this uncertainty, the Indigenous Australian languages are collectively covered by the technical term "Australian languages",[3] or the "Australian family".[lower-alpha 1]

The term can include both Tasmanian languages and the Western Torres Strait language,[5] but the genetic relationship to the mainland Australian languages of the former is unknown,[6] while that of the latter is Pama–Nyungan, though it shares features with the neighbouring Papuan Eastern Trans-Fly languages, in particular Meriam Mir, as well as the Papuan Tip Austronesian languages.[7] Most Australian Aboriginal languages belong to the Pama–Nyungan family, while the remainder are classified as "non-Pama–Nyungan", which is a term of convenience that does not imply a genealogical relationship.

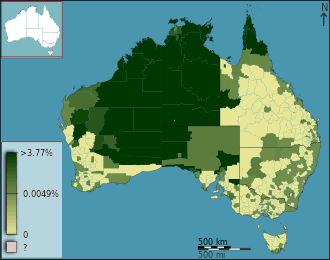

In the late 18th century, there were more than 250 distinct Aboriginal social groupings and a similar number of languages or varieties.[5] At the start of the 21st century, fewer than 150 Aboriginal languages remain in daily use,[8] and all except 13, which are still being transmitted to children, are highly endangered.[9] The surviving languages are located in the most isolated areas. Of the five least endangered Western Australian Aboriginal languages, four belong to the Ngaanyatjarra grouping of the Central and Great Victoria Desert.

Yolŋu languages from north-east Arnhem Land are also currently learned by children. Bilingual education is being used successfully in some communities. Seven of the most widely spoken Australian languages, such as Warlpiri, Murrinh-patha and Tiwi, retain between 1,000 and 3,000 speakers.[10] Some Aboriginal communities and linguists show support for learning programmes either for language revival proper or for only "post-vernacular maintenance" (teaching Indigenous Australians some words and concepts related to the lost language).[11]

Common features

Whether it is due to genetic unity or some other factor such as occasional contact, typologically the Australian languages form a language area or Sprachbund, sharing much of their vocabulary and many distinctive phonological features across the entire continent.

A common feature of many Australian languages is that they display so-called avoidance speech, special speech registers used only in the presence of certain close relatives. These registers share the phonology and grammar of the standard language, but the lexicon is different and usually very restricted. There are also commonly speech taboos during extended periods of mourning or initiation that have led to numerous Aboriginal sign languages.

For morphosyntactic alignment, many Australian languages have ergative–absolutive case systems. These are typically split systems; a widespread pattern is for pronouns (or first and second persons) to have nominative–accusative case marking and for third person to be ergative–absolutive, though splits between animate and inanimate are also found. In some languages the persons in between the accusative and ergative inflections (such as second person, or third-person human) may be tripartite: that is, marked overtly as either ergative or accusative in transitive clauses, but not marked as either in intransitive clauses. There are also a few languages which employ only nominative–accusative case marking.

Phonetics and phonology

Segmental inventory

A typical Australian phonological inventory includes just three vowels, usually /i, u, a/, which may occur in both long and short variants. In a few cases the [u] has been unrounded to give [i, ɯ, a].

There is almost never a voicing contrast; that is, a consonant may sound like a [p] at the beginning of a word, but like a [b] between vowels, and either symbol could be (and often is) chosen to represent it. Australia also stands out as being almost entirely free of fricative consonants, even of [h]. In the few cases where fricatives do occur, they developed recently through the lenition (weakening) of stops, and are therefore non-sibilants like [ð] rather than sibilants like [s] which are common elsewhere in the world. Some languages also have three rhotics, typically a flap, a trill, and an approximant; that is, like the combined rhotics of English and Spanish.

Besides the lack of fricatives, the most striking feature of Australian speech sounds is the large number of places of articulation. Nearly every language has four places in the coronal region, either phonemically or allophonically. This is accomplished through two variables: the position of the tongue (front or back), and its shape (pointed or flat). There are also bilabial, velar and often palatal consonants, but a complete absence of uvular or glottal consonants. Both stops and nasals occur at all six places, and in some languages laterals occur at all four coronal places.

A language which displays the full range of stops, nasals and laterals is Kalkatungu, which has labial p, m; "dental" th, nh, lh; "alveolar" t, n, l; "retroflex" rt, rn, rl; "palatal" ty, ny, ly; and velar k, ng. Wangganguru has all this, as well as three rhotics. Yanyuwa has even more contrasts, with an additional true dorso-palatal series, plus prenasalised consonants at all seven places of articulation, in addition to all four laterals.

A notable exception to the above generalisations is Kalaw Lagaw Ya, which has an inventory more like its Papuan neighbours than the languages of the Australian mainland, including full voice contrasts: /p b/, dental /t̪ d̪/, alveolar /t d/, the sibilants /s z/ (which have allophonic variation with [tʃ] and [dʒ] respectively) and velar /k ɡ/, as well as only one rhotic, one lateral and three nasals (labial, dental and velar) in contrast to the 5 places of articulation of stops/sibilants. Where vowels are concerned, it has 8 vowels with some morpho-syntactic as well as phonemic length contrasts (i iː, e eː, a aː, ə əː, ɔ ɔː, o oː, ʊ ʊː, u uː), and glides that distinguish between those that are in origin vowels, and those that in origin are consonants. Kunjen and other neighbouring languages have also developed contrasting aspirated consonants ([pʰ], [t̪ʰ], [tʰ], [cʰ], [kʰ]) not found further south.

Coronal consonants

Descriptions of the coronal articulations can be inconsistent.

The alveolar series t, n, l (or d, n, l) is straightforward: across the continent, these sounds are alveolar (that is, pronounced by touching the tongue to the ridge just behind the gum line of the upper teeth) and apical (that is, touching that ridge with the tip of the tongue). This is very similar to English t, d, n, l, though the Australian t is not aspirated, even in Kalaw Lagaw Ya, despite its other stops being aspirated.

The other apical series is the retroflex, rt, rn, rl (or rd, rn, rl). Here the place is further back in the mouth, in the postalveolar or prepalatal region. The articulation is actually most commonly subapical; that is, the tongue curls back so that the underside of the tip makes contact. That is, they are true retroflex consonants. It has been suggested that subapical pronunciation is characteristic of more careful speech, while these sounds tend to be apical in rapid speech. Kalaw Lagaw Ya and many other languages in North Queensland differ from most other Australian languages in not having a retroflexive series.

The dental series th, nh, lh are always laminal (that is, pronounced by touching with the surface of the tongue just above the tip, called the blade of the tongue), but may be formed in one of three different ways, depending on the language, on the speaker, and on how carefully the speaker pronounces the sound. These are interdental with the tip of the tongue visible between the teeth, as in th in English; dental with the tip of the tongue down behind the lower teeth, so that the blade is visible between the teeth; and denti-alveolar, that is, with both the tip and the blade making contact with the back of the upper teeth and alveolar ridge, as in French t, d, n, l. The first tends to be used in careful enunciation, and the last in more rapid speech, while the tongue-down articulation is less common.

Finally, the palatal series ty, ny, ly. (The stop is often spelled dj, tj, or j.) Here the contact is also laminal, but further back, spanning the alveolar to postalveolar, or the postalveolar to prepalatal regions. The tip of the tongue is typically down behind the lower teeth. This is similar to the "closed" articulation of Circassian fricatives (see Postalveolar consonant). The body of the tongue is raised towards the palate. This is similar to the "domed" English postalveolar fricative sh. Because the tongue is "peeled" from the roof of the mouth from back to front during the release of these stops, there is a fair amount of frication, giving the ty something of the impression of the English palato-alveolar affricate ch or the Polish alveolo-palatal affricate ć. That is, these consonants are not palatal in the IPA sense of the term, and indeed they contrast with true palatals in Yanyuwa. In Kalaw Lagaw Ya, the palatal consonants are sub-phonemes of the alveolar sibilants /s/ and /z/.

These descriptions do not apply exactly to all Australian languages, as the notes regarding Kalaw Lagaw Ya demonstrate. However, they do describe most of them, and are the expected norm against which languages are compared.

Orthography

Probably every Australian language with speakers remaining has had an orthography developed for it, in each case in the Latin script. Sounds not found in English are usually represented by digraphs, or more rarely by diacritics, such as underlines, or extra symbols, sometimes borrowed from the International Phonetic Alphabet. Some examples are shown in the following table.

| Language | Example | Translation | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pitjantjatjara | paṉa | 'earth, dirt, ground; land' | diacritic (underline) indicates retroflex 'n' |

| Wajarri | nhanha | 'this, this one' | digraph indicating 'n' with dental articulation |

| Yolŋu | yolŋu | 'person, man' | 'ŋ' (from IPA) for velar nasal |

Classification

Internal

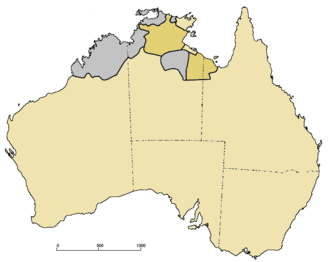

Most Australian languages are commonly held to belong to the Pama–Nyungan family, a family accepted by most linguists, with Robert M. W. Dixon as a notable exception. For convenience, the rest of the languages, all spoken in the far north, are commonly lumped together as "Non-Pama–Nyungan", although this does not necessarily imply that they constitute a valid clade. Dixon argues that after perhaps 40,000 years of mutual influence, it is no longer possible to distinguish deep genealogical relationships from areal features in Australia, and that not even Pama–Nyungan is a valid language family.[12]

However, few other linguists accept Dixon's thesis. For example, Kenneth L. Hale describes Dixon's skepticism as an erroneous phylogenetic assessment which is "such an insult to the eminently successful practitioners of Comparative Method Linguistics in Australia, that it positively demands a decisive riposte".[13] Hale provides pronominal and grammatical evidence (with suppletion) as well as more than fifty basic-vocabulary cognates (showing regular sound correspondences) between the proto-Northern-and-Middle Pamic (pNMP) family of the Cape York Peninsula on the Australian northeast coast and proto-Ngayarta of the Australian west coast, some 3,000 kilometres (1,900 mi) apart, to support the Pama–Nyungan grouping, whose age he compares to that of Proto-Indo-European.

Johanna Nichols suggests that the northern families may be relatively recent arrivals from Maritime Southeast Asia, perhaps later replaced there by the spread of Austronesian. That could explain the typological difference between Pama–Nyungan and non-Pama–Nyungan languages, but not how a single family came to be so widespread. Nicholas Evans suggests that the Pama–Nyungan family spread along with the now-dominant Aboriginal culture that includes the Australian Aboriginal kinship system.

In late 2017, Mark Harvey and Robert Mailhammer published a study in Diachronica that hypothesised, by analysing noun class prefix paradigms across both Pama-Nyungan and the minority non-Pama-Nyungan languages, that a Proto-Australian could be reconstructed from which all known Australian languages descend. This Proto-Australian language, they concluded, would have been spoken about 12,000 years ago in northern Australia.[14][15][16]

External

For a long time unsuccessful attempts were made to detect a link between Australian and Papuan languages, the latter being represented by those spoken on the coastal areas of New Guinea facing the Torres Strait and the Arafura Sea.[17] In 1986 William A. Foley noted lexical similarities between Robert M. W. Dixon's 1980 reconstruction of proto-Australian and the East New Guinea Highlands languages. He believed that it was naïve to expect to find a single Papuan or Australian language family when New Guinea and Australia had been a single landmass (called the Sahul continent) for most of their human history, having been separated by the Torres Strait only 8000 years ago, and that a deep reconstruction would likely include languages from both. Dixon, in the meantime, later abandoned his proto-Australian proposal.[18]

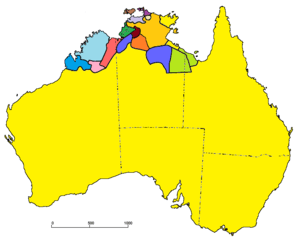

Families

Bowern (2011)

According to Claire Bowern's Australian Languages (2011), Australian languages divide into approximately 30 primary sub-groups and 5 isolates.[1]

- Presumptive isolates:

- Previously established families:

- Newly proposed families:

- Mirndi (5–7)

- Darwin Region (4)

- Macro-Gunwinyguan languages (22)

- Greater Pama–Nyungan:

- Tangkic (5)

- Garawan (3)

- Pama–Nyungan proper (approximately 270 languages)

- Western and Northern Tasmanian (extinct)

- Northeastern Tasmanian (extinct)

- Eastern Tasmanian (extinct)

Glottolog 4.1 (2019)

Glottolog 4.1 (2019) recognizes 23 independent families and 9 isolates in Australia, comprising a total of 32 independent language groups.[19]

|

|

Survival

It has been inferred from the probable number of languages and the estimate of pre-contact population levels that there may have been from 3,000 - 4,000 speakers on average for each of the 250 languages.[20] A number of these languages were almost immediately wiped out within decades of colonisation, the case of the Aboriginal Tasmanians being one notorious example of precipitous linguistic ethnocide. Tasmania had been separated from the mainland at the end of the Quaternary glaciation, and Indigenous Tasmanians remained isolated from the outside world for around 12,000 years. Claire Bowern has concluded in a recent study that there were twelve Tasmanian languages, and that those languages are unrelated (that is, not demonstrably related) to those on the Australian mainland.[21]

In 1990 it was estimated that 90 languages still survived of the approximately 250 once spoken, but with a high rate of attrition as elders died out. Of the 90, 70% by 2001 were judged as 'severely endangered' with only 17 spoken by all age groups, a definition of a 'strong' language.[22] On these grounds it is anticipated that despite efforts at linguistic preservation, many of the remaining languages will disappear within the next generation. The overall trend suggests that in the not too distant future all of the Indigenous languages will be lost, perhaps by 2050,[23] and with them the cultural knowledge they convey.[24]

During the period of the stolen generations, Aboriginal children were removed from their families and placed in institutions where they were punished for speaking their Indigenous language. Different, mutually unintelligible language groups were often mixed together, with Australian Aboriginal English or Australian Kriol language as the only lingua franca. The result was a disruption to the inter-generational transmission of these languages that severely impacted their future use. Today, that same transmission of language between parents and grandparents to their children is a key mechanism for reversing language shift.[25] For children, proficiency in the language of their cultural heritage has a positive influence on their ethnic identity formation, and it is thought to be of particular benefit to the emotional well-being of Indigenous children. There is some evidence to suggest that the reversal of the Indigenous language shift may lead to decreased self-harm and suicide rates among Indigenous youth.[26]

The first Aboriginal people to use Australian Aboriginal languages in the Australian parliament were Aden Ridgeway on 25 August 1999 in the Senate when he said "On this special occasion, I make my presence known as an Aborigine and to this chamber I say, perhaps for the first time: Nyandi baaliga Jaingatti. Nyandi mimiga Gumbayynggir. Nya jawgar yaam Gumbyynggir"[27] and in the House of Representatives on 31 August 2016 Linda Burney gave an acknowledgment of country in Wiradjuri in her first speech[28] and was sung in by Lynette Riley in Wiradjuri from the public gallery.[29]

Preservation measures

2019 was the International Year of Indigenous Languages (IYIL2019), as declared by the United Nations General Assembly. The commemoration was used to raise awareness of and support for the preservation of Aboriginal languages within Australia, including spreading knowledge about the importance of each language to the identity and knowledge of Indigenous groups. Warrgamay/Girramay man Troy Wyles-Whelan joined the North Queensland Regional Aboriginal Corporation Language Centre (NQRACLC) in 2008, and has been contributing oral histories and the results of his own research to their database.[30] As part of the efforts to raise awareness of Wiradjuri language a Grammar of Wiradjuri language[31] was published in 2014 and A new Wiradjuri dictionary[32] in 2010.[33]

The New South Wales Aboriginal Languages Act 2017 became law on 24 October 2017.[34] It was the first legislation in Australia to acknowledge the significance of first languages.[35]

In 2019 the Royal Australian Mint issued a 50 cent coin to celebrate the International Year of Indigenous Languages which features 14 different words for “money” from Australian Indigenous languages.[36][37] The coin was designed by Aleksandra Stokic in consultation with Indigenous language custodian groups.[37]

The collaborative work of digitising and transcribing many word lists created by ethnographer Daisy Bates in the 1900s at Daisy Bates Online[38] provides a valuable resource for those researching especially Western Australian languages, and some languages of the Northern Territory and South Australia.[39] The project is co-ordinated by Nick Thieburger, who works in collaboration with the National Library of Australia "to have all the microfilmed images from Section XII of the Bates papers digitised", and the project is ongoing.[40]

Living Aboriginal languages

The National Indigenous Languages Report is a regular Australia-wide survey of the status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages[41] conducted in 2005,[42] 2014[43] and 2019.[41]

Languages with more than 100 speakers:

- New South Wales:

- 3 languages (~ 600):

- Yugambeh-Bundjalung

- Bundjalung (~ 100)

- Yugambeh (~ 20; shared with Queensland)

- Githabul (~ 10; shared with Queensland)

- Wiradjuri (~ 500)

- Gamilaraay (~ 100)

- Yugambeh-Bundjalung

- 3 languages (~ 600):

- Victoria:

- N/A

- Tasmania:

- N/A

- South Australia:

- 4 languages (~ 3,900):

- Ngarrindjeri (~ 300)

- Adyamathanha (~ 100)

- Yankunytjatjara (~ 400)

- Pitjantjatjara (~ 3,100; shared with Northern Territory and Western Australia)

- 4 languages (~ 3,900):

- Queensland:

- 5 languages (~ 1,800):

- Kuku Yalanji (~ 300)

- Guugu Yimidhirr (~ 800)

- Kuuk Thaayore (~ 300)

- Wik Mungkan (~ 400)

- 5 languages (~ 1,800):

- Western Australia:

- 17 languages (~ 8,000):

- Noongar (~ 500)

- Wangkatha (~ 300)

- Ngaanyatjarra (~ 1,000)

- Manytjilyitjarra (~ 100)

- Martu Wangka (~ 700)

- Panyjima (~ 100)

- Yinjibarndi (~ 400)

- Nyangumarta (~ 200)

- Bardi (~ 400)

- Wajarri (~ 100)

- Pintupi (~ 100; shared with Northern Territory)

- Pitjantjatjara (~3,100; shared with Northern Territory and South Australia)

- Kukatja (~ 100)

- Walmatjarri (~ 300)

- Gooniyandi (~ 100)

- Djaru (~ 200)

- Kija (~ 200)

- Miriwoong (~ 200)

- 17 languages (~ 8,000):

- Northern Territory:

- 19 languages (~ 28,100):

- Luritja (~ 1,000)

- Upper Arrernte (~ 4,500)

- Warlpiri (~ 2,300)

- Kaytetye (~ 100)

- Warumungu (~ 300)

- Gurindji (~ 400)

- Murrinh Patha (~ 2,000)

- Tiwi (~ 2,000)

- Pintupi (~ 100; shared with Western Australia)

- Pitjantjatjara (~3,100; shared with Western Australia and South Australia)

- Iwaidja (~ 100)

- Maung (~ 400)

- Kunwinjku (~ 1,800)

- Burarra (~ 1,000)

- Dhuwal (~4,200)

- Djinang (~ 100)

- Nunggubuyu (~ 300)

- Anindilyakwa (~ 1,500)

- 19 languages (~ 28,100):

Total 46 languages, 42,300 speakers, with 11 having only approximately 100. 11 languages have over 1,000 speakers.

- Creoles:

- Kriol (~ 20,000)

See also

- Aboriginal Australians

- Australian Aboriginal sign languages

- List of Aboriginal Australian group names

- List of Australian Aboriginal languages

- List of Australian place names of Aboriginal origin

- List of endangered languages with mobile apps

- List of reduplicated Australian place names

- Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages

- Macro-Gunwinyguan languages

- Macro-Pama–Nyungan languages

Notes

- "Dixon (1980) claimed that all but two or three of the 200 languages of Australia can be shown to belong to one language family – the 'Australian family'. In the same way that most of the languages of Europe and Western Asia belong to the Indo-European family."[4]

Citations

- Bowern 2011.

- Bowern & Atkinson 2012, p. 830.

- Dixon 2011, pp. 253–254.

- Dixon 1980, p. 3.

- Walsh 1991, p. 27.

- Bowern 2012, p. 4593.

- Mitchell 2015.

- Dalby 2015, p. 43.

- Goldsworthy 2014.

- UNESCO atlas (online)

- Zuckermann 2009.

- Dixon 2002: 48,53

- O'Grady & Hale 2004, p. 69.

- ABC 2018.

- BBC 2018.

- Harvey & Mailhammer 2017, pp. 470–515.

- Pereltsvaig 2017, p. 278.

- Dixon 2002, pp. xvii,xviii.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2019). "Glottolog". 4.1. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- McConvell & Thieberger 2001, p. 16.

- Bowern 2012, pp. 4590,4593.

- McConvell & Thieberger 2001, pp. 17,61.

- Forrest 2017, p. 1.

- McConvell & Thieberger 2001, p. 96.

- Forrest 2017.

- Hallett, Chandler & Lalonde 2007, pp. 392–399.

- "Senate Official Hansard No. 198, 1999 Wednesday 25 August 1999". Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "First Speech: Hon Linda Burney MP". Commonwealth Parliament. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Battin, Jacqueline (21 May 2018). "Indigenous Languages in Australian Parliaments". Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Wyles 2019.

- Grant, Stan; Rudder, John, (author.) (2014), A grammar of Wiradjuri language, Rest, ISBN 978-0-86942-151-2CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Grant, Stan; Grant, Stan, 1940-; Rudder, John (2010), A new Wiradjuri dictionary, Restoration House, ISBN 978-0-86942-150-5CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Wiradjuri Resources". Australian Aboriginal Languages Student Blog. 6 May 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Aboriginal Languages Act 2017 No 51". NSW Legislation. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Protecting NSW Aboriginal languages | Languages Legislation | Aboriginal Affairs NSW". NSW Aboriginal Affairs. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "International Year of Indigenous Languages commemorated with new coins launched by Royal Australian Mint and AIATSIS". Royal Australian Mint. 8 April 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Meakins, Felicity; Walsh, Michael. "The 14 Indigenous words for money on our new 50 cent coin". The Conversation. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Digital Daisy Bates". Digital Daisy Bates. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "Map". Digital Daisy Bates. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "Technical details". Digital Daisy Bates. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "National Indigenous Languages Report (NILR)". Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005". Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. 19 February 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "Community, identity, wellbeing: The report of the Second National Indigenous Languages Survey". Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. 16 February 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

Sources

- Bowern, C. 2011. Oxford Bibliographies Online: Australian Languages

- McConvell, Patrick & Claire Bowern. 2011. The prehistory and internal relationships of Australian languages. Language and Linguistics Compass 5(1). 19–32.

- David Marchese (28 March 2018). "Indigenous languages come from just one common ancestor, researchers say". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Australia's indigenous languages have one source, study says". BBC News. 28 March 2018.

- Bowern, Claire (23 December 2011). "How many languages were spoken in Australia?". Anggarrgoon. Retrieved 30 March 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bowern, Claire (2012). "The riddle of Tasmanian languages". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 279 (1747): 4590–4595. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.1842. PMC 3479735. PMID 23015621.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bowern, Claire; Atkinson, Quentin (2012). "Computational Phylogenetics and the Internal Structure of Pama-Nyungan". Language. 84 (4): 817–845. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.691.3903. doi:10.1353/lan.2012.0081.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dalby, Andrew (2015). Dictionary of Languages: The definitive reference to more than 400 languages. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-408-10214-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dixon, R. M. W. (1980). The Languages of Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29450-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dixon, R. M. W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47378-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dixon, R. M. W. (2011). Searching for Aboriginal Languages: Memoirs of a Field Worker. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-02504-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Nicholas, ed. (2003). The Non-Pama-Nyungan Languages of Northern Australia: Comparative Studies of the Continent's Most Linguistically Complex Region. Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-858-83538-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Forrest, Walter (June 2017). "The intergenerational transmission of Australian Indigenous languages: why language maintenance programmes should be family-focused". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 41 (2): 303–323. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1334938.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldsworthy, Anna (September 2014). "In Port Augusta, an Israeli linguist is helping the Barngarla people reclaim their language". The Monthly.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hallett, Darcy; Chandler, Michael J.; Lalonde, Christopher E. (July–September 2007). "Aboriginal language knowledge and youth suicide". Cognitive Development. 22 (3): 392–399. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.134.3386. doi:10.1016/j.cogdev.2007.02.001.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harvey, Mark; Mailhammer, Robert (2017). "Reconstructing remote relationships: Proto-Australian noun class prefixation". Diachronica. 34 (4): 470–515. doi:10.1163/187740911x558798.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hunter, Jessica; Bowern, Claire; Round, Erich (2011). "Reappraising the Effects of Language Contact in the Torres Strait". Journal of Language Contact. 4 (1): 106–140. doi:10.1163/187740911x558798.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McConvell, P.; Thieberger, Nicholas (November 2001). State of Indigenous languages in Australia 2001 (PDF). Department of the Environment and Heritage.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McConvell, Patrick; Evans, Nicholas, eds. (1997). Archaeology and linguistics: aboriginal Australia in global perspective. Oxford University Press Australia. ISBN 978-0-195-53728-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Rod (April 2015), "Ngalmun Lagaw Yangukudu: The Language of our Homeland in Goemulgaw Lagal: Cultural and Natural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait", Memoirs of the Queensland Museum – Culture, 8 (1): 323–446, ISSN 1440-4788

- O'Grady, Geoffrey; Hale, Ken (2004). "The Coherence and Distinctiveness of the Pama–Nyungan Language Family within the Australian Linguistic Phylum". In Bowern, Claire; Koch, Harold (eds.). Australian Languages: Classification and the comparative method. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 69–92. ISBN 978-9-027-29511-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pereltsvaig, Asya (2017). Languages of the World: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-17114-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walsh, Michael (1991). "Overview of indigenous languages of Australia". In Romaine, Suzanne (ed.). Language in Australia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 27–48. ISBN 978-0-521-33983-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wyles, Dwayne (2 June 2019). "Preserving Indigenous languages in IYIL2019 helps custodians heal, taps into knowledge of country". ABC News. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (26 August 2009). "Aboriginal languages deserve revival". The Australian. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad; Walsh, Michael (2011). "Stop, Revive, Survive: Lessons from the Hebrew Revival Applicable to the Reclamation, Maintenance and Empowerment of Aboriginal Languages and Cultures" (PDF). Australian Journal of Linguistics. 31 (1): 111–127. doi:10.1080/07268602.2011.532859.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

| Library resources about Australian Aboriginal languages |

- Simpson, Jane (21 January 2019). "The state of Australia's Indigenous languages – and how we can help people speak them more often". The Conversation.

- AUSTLANG Australian Indigenous Languages Database at AIATSIS

- Aboriginal Australia map, a guide to Aboriginal language, tribal and nation groups published by AIATSIS

- Aboriginal Languages of Australia

- The AIATSIS map of Aboriginal Australia (recorded ranges; full view here

- Languages of Australia, as listed by Ethnologue

- Report of the Second National Indigenous Languages Survey 2014

- Finding the meaning of an Aboriginal word

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Social Justice Report 2009 for more information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages and policy.

- Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages (Northern Territory languages only)

- Bowern, Claire. 2016. “Chirila: Contemporary and Historical Resources for the Indigenous Languages of Australia.” Language Documentation and Conservation 10 (2016): 1–44. http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/?p=1002.