No. 88 Squadron RAF

Number 88 Squadron was an aircraft squadron of the Royal Air Force. It was formed at Gosport, Hampshire in July 1917 as a Royal Flying Corps (RFC) squadron.[4]

| No. 88 (Hong Kong) Squadron | |

|---|---|

| Active | 24 July 1917 – 1 April 1918 (RFC) 1 April 1918 – 10 August 1919 (RAF) 17 June 1937 – 4 April 1945 1 September 1946 – 1 October 1954 15 January 1956 – 17 December 1962 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Flying squadron |

| Motto(s) | French: En garde ("Be on your guard")[1] |

| Insignia | |

| Squadron Badge heraldry | A serpent gliding.The snake is based on the 1914-18 War badge of No.88 Squadron of the French Air Service (Escadrille SPA.88) with which this squadron was associated. The compliment of adopting this badge was warmly welcomed by the French Air Service at that time.[2] Approved by King George VI in November 1939.[3] |

| Squadron codes | HY (Apr 1939 – Sep 1939) RH (Sep 1939 – Apr 1945) |

First World War

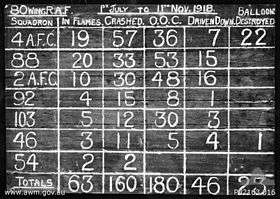

After forming at Gosport in July 1917, the squadron was moved to France in April 1918 where it undertook fighter-reconnaissance duties. It was also involved in the development of air-to-air wireless telegraphy. The squadron became part of No. 80 Wing, which specialised in attacks on German airfields, on 1 July 1918, shortly after the foundation of the Royal Air Force on 1 April.

Despite its short service at the front, the squadron claimed 147 victories for casualties of two killed in action, five wounded in action, and ten missing. Eleven aces served in the unit, including Kenneth Burns Conn, Edgar Johnston, Allan Hepburn, Charles Findlay, and Gerald Anderson.[5] It was disbanded on 10 August 1919.[6]

Second World War

On 7 June 1937, No. 88 Squadron was reformed at RAF Waddington as a light-bomber squadron equipped with the Hawker Hind biplane, moving to RAF Boscombe Down in July that year. In December that year it re-equipped with the Fairey Battle monoplane bomber.[7][8]

On the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, the squadron transferred from No. 1 Group to the RAF Advanced Air Striking Force, making it one of the first squadrons to be sent to France.[9][8][10] The first recorded RAF "kill" of the Second World War was claimed on 20 September 1939 by air observer Sergeant F Letchford aboard a Fairey Battle flown by Flying Officer LH Baker.[11][2] It suffered very heavy losses during the Battle of France,[11] for example, when four Battles set out from its base at Mourmelon to attack German troop columns in Luxembourg, only 1 returned. (Four out of four Battles from No. 218 Squadron launched against the same targets that day were also lost.)[12] The squadron was forced to retreat on 15 May, with any unserviceable aircraft being destroyed, together with stocks of spares and stores. For the rest of the squadrons time in France, it was confined mainly to night operations to minimise losses.[13] It returned to Britain in June 1940, moving to RAF Sydenham, Belfast where it operated a mix of Battles, Douglas Boston Is and Bristol Blenheim IVs, carrying out patrol duties over the Western Approaches.

In July 1941, the squadron was moved to RAF Swanton Morley, East Anglia where it converted fully to the Boston III and IIIA. The aircraft was well received by the crews. In January 1942 Wing Commander James Pelly-Fry took over as commanding officer. He was a well experienced pilot who had flown in Africa.[14] Pelly-Fry led a series of circus missions over northern France, bombing targets while under heavy fighter escort, including the bombing of the Saint-Malo docks on 31 July 1942. On 19 August 1942 the squadron supported Canadian forces during the intense air battles of the Dieppe raid, where the RAF lost 91 aircraft. It flew repeated sorties attempting to destroy field gun positions overlooking the beaches at Dieppe. In September the squadron was moved to RAF Oulton in Norfolk, where it became an integral part of No. 2 Group. The crews were billeted at Blickling Hall, a stately home north of Aylsham in Norfolk. From Oulton the squadron carried out attacks on German coastal shipping, coastal targets and targets in northern France. On 6 December 1942, the squadron was the lead element in Operation Oyster, the daylight raid against the Philips works in Eindhoven. The raid was the most famous and successful raid conducted by No. 2 Group.

In August 1943, the squadron relocated to RAF Hartford Bridge, Hampshire with its sister squadron No. 342 Squadron as part of No. 137 Wing of No. 2 Group of the 2nd Tactical Air Force in preparation for the invasion of Europe. From there the squadron attacked German communications and airfields. On D-Day itself it was charged with laying the smokescreen to hide the first wave of landing craft.

In October 1944, the squadron returned to France based at Vitry-en-Artois to join the tactical air forces that were supporting the Allied armies as they advanced across Europe. The squadron was finally disbanded on 4 April 1945.[6]

Post-War

On 1 September 1946, No. 1430 Flight at RAF Kai Tak, Hong Kong, equipped with Short Sunderland flying boats, was redesignated No. 88 Squadron. It was initially employed on transport duties, ferrying passengers, mail and freight from Hong Kong to Iwakuni in Japan in support of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force.[9][15][16] The squadron later became a General Reconnaissance unit, adding maritime patrol and anti-piracy operations to its transport duties.[9][15] By April 1949, the Chinese Civil War was approaching its conclusion, with Chinese Communist forces advancing towards Shanghai. When the Royal Navy ship HMS Amethyst, on her way up the Yangtze river to Nanjing to relieve HMS Consort as guard ship, came under fire from People's Liberation Army artillery and ran aground on 20 April in what became known as the Yangtze Incident, one of the squadron's Sunderlands was deployed in support of British efforts to relieve Amethyst, alighting on the Yangtze near Amethyst on 21 April. Although the Sunderland came under fire after alighting, a doctor and medical supplies were transferred to the ship by boat. A second attempt on 22 April was less successful, the Sunderland being forced to take off without making any transfers to or from Amethyst.[17][18] The squadron's Sunderlands helped to evacuate British subjects from Shanghai on 17 May.[19][20] The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, saw the squadron fly patrols along the Korean coast, with detachments operating from Iwakuni. In June 1951 the squadron moved to RAF Seletar in Singapore, with its patrol duties off Korea being passed on to other Sunderland squadrons. It was disbanded on 1 October 1954.[9][15]

On 15 January 1956, No. 88 Squadron reformed at RAF Wildenrath as an interdiction squadron equipped with English Electric Canberra B(I)8s, with a main role of low-level night ground attack.[21] From January 1958, it added nuclear strike, using US-owned Mark 7 nuclear bombs supplied under Project E to its conventional attack duties.[22] In July 1958, the squadron was deployed to RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus due to fears that the Lebanon crisis might escalate,[23] and in June 1961, it was briefly deployed to Sharjah in response to Iraqi threats against Kuwait.[24][25] On 17 December 1962, the squadron was renumbered No. 14 Squadron.[9]

Air Training Corps

In 2014, No. 88 (Battle) Squadron of the Air Training Corps was created, the squadron being located in Battle, East Sussex, UK. The Squadron Commander selected the number 88 in memory of the Fairey Battle aircraft which the original squadron had used. In 2019 No 88 (Battle) Squadron was voted the most improved Air Cadet Squadron in the UK winning the Marshall Trophy.

Aircraft operated

Aircraft operated include:[26]

- Bristol F.2b (March 1918 – August 1919)

- Hawker Hind (June 1937 – December 1937)

- Fairey Battle (December 1937 – August 1941)

- Bristol Blenheim Mk.I (February 1941 – July 1941)

- Douglas Boston Mk.I (February 1941 – August 1941)

- Douglas Boston Mk.II (February 1941 – August 1941)

- Bristol Blenheim Mk.IV (July 1941 – February 1942)

- Douglas Boston Mk.III (July 1941 – June 1943)

- Douglas Boston Mk.IIIa (March 1943 – April 1945)

- Douglas Boston Mk.IV (June 1944 – April 1945)

- Short Sunderland GR.5 (September 1946 – October 1954)

- English Electric Canberra B(I).8 (January 1956 – December 1962)

See also

- Cathay Pacific VR-HEU

References

- Pine, L.G. (1983). A dictionary of mottoes (1 ed.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 64. ISBN 0-7100-9339-X.

- "88 Squadron". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016.

- "88 Sqn". RAF Heraldry Trust. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Gutman, J. "Bristol F2 Fighter Aces of World War 1". Osprey Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-1-84603-201-1

- "No. 88 Squadron". The Aerodrome. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "88 Squadron". Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Halley 1980, pp. 126–127

- Moyes 1964, pp. 118–119

- Halley 1980, p. 126

- Richards 1953, p. 406

- Moyes 1964, p. 118

- Gifford 2004, pp. 20, 23

- Gifford 2004, p. 24

- "Private Papers of Group Captain J E Pelly-Fry, DSO". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Rawlings 1982, p. 96

- "From All Quarters: Japan Courier Service". Flight. Vol. LIII no. 2053. 29 April 1948. p. 477. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Delve 1989, pp. 45–46

- "Sunderland's Sorties on the Yangtse". Flight. Vol. LV no. 2107. 12 May 1949. p. 574. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Delve 1989, p. 47

- "Service Aviation: Sunderlands Evacuate Shanghai". Flight. Vol. LV no. 2110. 2 June 1949. p. 664. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Jackson 1988, pp. 40–41

- Brookes 2014, pp. 78–80

- Brookes 2014, p. 78

- Jackson 1988, p. 56

- Brookes 2014, p. 79

- "No 88 Squadron Aircraft & Markings". Air of Authority - A History of RAF Organisation. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Bowyer, Michael J. F. (1974). 2 Group R.A.F.: A Complete History, 1939–1945. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-09491-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brookes, Andrew (2014). RAF Canberra Units of the Cold War. Osprey Combat Aircraft. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-411-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delve, Ken (January–April 1989). "Sunderland up the Yangtze". Air Enthusiast. No. 38. pp. 45–47. ISSN 0143-5450.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halley, James J. (1980). The Squadrons of the Royal Air Force. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air Britain (Historians) Ltd. ISBN 0-85130-083-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gifford, Simon (January–February 2004). "Lost Battles : The Carnage of May 10 to May 16, 1940". Air Enthusiast. No. 109. pp. 0143–5450.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Robert (1988). Canberra: The Operational Record. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85310-049-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moyes, Philip (1964). Bomber Squadrons of the R.A.F. and their Aircraft. London: Macdonald and Co. (Publishers) Ltd.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rawlings, John D. R. (1982). Coastal, Support and Special Squadrons of the RAF and their Aircraft. London: Jane's Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7106-0187-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richards, Denis (1953). Royal Air Force 1939–1945: Volume I: The Fight at Odds. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to No. 88 Squadron RAF. |