No. 80 Wing RAF

No. 80 Wing RAF was a unit of the Royal Air Force (RAF) during both World Wars and briefly in the 1950s. In the last months of World War I it controlled RAF and Australian Flying Corps (AFC) fighter squadrons. It was reformed in 1940 to operate electronic countermeasures in the Battle of the Beams.

| No. 80 Wing RAF | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1 July 1918–1 March 1919 7 October 1940–24 September 1945 1 August 1953–15 March 1957 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Royal Air Force |

| Role | Air superiority (WWI) Electronic Countermeasures (WWII) |

| Size | Wing |

| Part of | No. 100 Group RAF (1943–45) |

| Garrison/HQ | Serny (WWI) RAF Radlett (WWII) |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | Wing Commander Edward Addison (1940–43) |

First World War

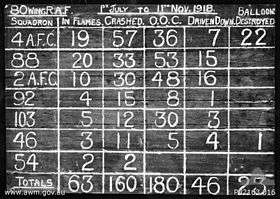

No. 80 Wing was formed at Serny, Pas-de-Calais, on 1 July 1918, as an Army Wing of squadrons equipped with scout (fighter) aircraft.[1][2] From 26 June, it was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Louis Strange.

The wing specialised in large-scale raids against German Luftstreitkräfte airfields.

Its subordinate squadrons were:

Second World War

In June 1940, a RAF Radio Counter-Measures (RCM) unit was formed at a requisitioned country hotel, Aldenham Lodge, in Radlett, Hertfordshire, to provide electronic countermeasures (ECM) and intelligence on enemy radio/radar systems.[3] On 7 October, it was renamed 80 (Signals) Wing,[2] with the motto "Confusion to Our Enemies". 80 Wing worked under the immediate control of the Air Ministry, but kept in close touch with RAF Fighter Command's operations room at RAF Bentley Priory.[4]

The main role of RCM/80 Wing initially was jamming the German radio navigation system Knickebein, which assisted Luftwaffe bombers raiding targets in the UK. Its founding commander was Wing Commander Edward Addison, a signals specialist who had recently returned from the Middle East. The technical design of countermeasures was handled by a section under Dr Robert Cockburn at the Telecommunications Research Establishment at Swanage, Dorset. Both organisations were given the highest priority.[5]

The first jammers developed at Swanage were simple diathermy sets to transmit a 'mush' of noise on the Knickebein frequency. These were quickly superseded by higher powered equipment called 'Aspirins' (to deal with the Knickebein beams, which were codenamed 'Headaches').[5] Knickebein was soon superseded by X-Gerät and Y-Gerät directional beams, which in turn were eventually jammed by 80 Wing in the ongoing Battle of the Beams.[6][7]

On 23/24 April 1942, the Luftwaffe began a new campaign against the UK (the Baedeker Blitz ) with a sharp raid on Exeter, followed by a series of raids on other provincial cities. Scientific intelligence gave about six weeks' warning that these raids would employ X-Gerät with a new supersonic modulation frequency. 80 Wing was able to add supersonic modulation to its jammers, but was briefed not to employ this countermeasure until listening stations had confirmed that the Luftwaffe was indeed using the new technique. Unfortunately, the designers of the listening receivers had overlooked the fact that supersonic reception involves a wider bandwidth than normal in the high frequency circuits of the receivers. Once this was corrected, 80 Wing was able to jam the beam so successfully that the 50 per cent success rate (bombs on target) of the early Baedeker raids dropped to 13 per cent and the campaign petered out. The Air Staff's scientific intelligence adviser, Dr R.V. Jones, estimated that the delay in allowing 80 Wing to begin jamming cost about 400 lives and another 600 serious injuries, while Anti-Aircraft Command was forced to redeploy hundreds of guns to cover potential Baedeker targets.[8][9][10]

By the end of 1942, 80 Wing included a flying unit, known as the Wireless Intelligence and Development Unit (WIDU) at RAF Boscombe Down in Wiltshire, which was later renamed No. 109 Squadron RAF.[3] Among other roles, 109 Sqn simulated enemy air raids, to test ECM equipment.

The headquarters of 80 Wing later moved to the Handley-Page factory aerodrome at Radlett, also known as RAF Radlett. From November 1943, it became part of No. 100 Group RAF – a larger formation based at Radlett devoted to ECM and commanded by Addison (by now promoted to Air commodore and later to Air vice-marshal).[11][12] The wing controlled Meacon beacons, as well as other countermeasures and radio/radar intelligence work.

At it peak, the wing included 2,000 personnel. It was disbanded on 24 September 1945.[2][3]

Postwar

No. 80 Wing RAF was reformed on 1 August 1953 and disbanded on 15 March 1957.[2]

See also

- No. 80 Wing RAAF – a joint RAAF-RAF fighter wing that saw action in the South West Pacific Area during 1943–45.

- List of Wings of the Royal Air Force

Notes

- Air Ministry, 1938, "80 Wing R.A.F.", Air Historical Branch: Papers (Series I), AIR 1/1938/204/245/8.

- Wings 51–110 at Air of Authority.

- BBC, 2005, The War in 80 (Signals) Wing RAF (22 June 2016).

- Collier, Chapter IX.

- Jones, p. 176.

- Jones, pp. 186–238.

- Collier, Chapter XVII.

- Jones, pp. 323–6.

- Routledge, pp. 402–3.

- Collier, Chapter XX.

- Jones, p. 588.

- Falconer, p. 33.

References

- Basil Collier, History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series: The Defence of the United Kingdom, London: HM Stationery Office, 1957.

- Jonathan Falconer, Bomber Command Handbook 1939–1945, Stroud: Sutton, 1998, ISBN 0-7509-1819-5.

- R.V. Jones, Most Secret War: British Scientific Intelligence 1939–1945, London: Hamish Hamilton 1978/Coronet 1979, ISBN 0-340-24169-1.

- Brig N.W. Routledge, History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery: Anti-Aircraft Artillery 1914–55, London: Royal Artillery Institution/Brassey's, 1994, ISBN 1-85753-099-3,